- Home

- Physical Activity and Health

- Kinesiology/Exercise and Sport Science

- Coaching and Officiating

- Sociology of Sport

- Physical Education

- Best Practice for Youth Sport

Although the physical and psychological benefits of youth participating in sport are evident, the increasing professionalization and specialization of youth sport, primarily by coaches and parents, are changing the culture of youth sport and causing it to erode the ideal mantra: “It’s all about the kids.”

In Best Practice for Youth Sport, readers will gain an appreciation of an array of issues regarding youth sport. This research-based text is presented in a practical manner, with examples from current events that foster readers’ interest and class discussion. The content is based on the principle of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP), which can be defined as engaging in decisions, behaviors, and policies that meet the physical, psychological, and social needs of children and youth based on their ages and maturational levels. This groundbreaking resource covers a breadth of topics, including bone development, burnout, gender and racial stereotypes, injuries, motor behavior, and parental pressures.

Written by Robin S. Vealey and Melissa A. Chase, the 16 chapters of Best Practice for Youth Sport are divided into four parts. Part I, Youth Sport Basics, provides readers with the fundamental knowledge and background related to the history, evolution, and organization of youth sport. Part II, Maturation and Readiness for Youth Sport Participants, is the core of understanding how and why youth sport is different from adult sport. This part details why it is important to know when youth are ready to learn and compete. Part III, Intensity of Participation in Youth Sport, examines the appropriateness of physical and psychological intensity at various developmental stages and the potential ramifications of overtraining, overspecialization, overstress, and overuse. The text concludes with part IV, Social Considerations in Youth Sport, which examines how youth sport coaches and parents can help create a supportive social environment so that children can maximize the enjoyment and benefits from youth sport.

In addition to 14 appendixes, activities, glossaries, study questions, and other resources that appear in Best Practice for Youth Sport, the textbook is enhanced with instructor ancillaries: a test package, image bank, and instructor guide that features a syllabus, additional study questions and learning activities, tips on teaching difficult concepts, and additional readings and resources. These specialized resources ensure that instructors will be ready for each class session with engaging materials.

Best Practice for Youth Sport provides readers with knowledge of sport science concerning youth sport and engages them through the use of anecdotes, activities, case studies, and practical strategies. Armed with the knowledge from this text, students, coaches, parents, administrators, and others will be able to become active agents of social change in structuring and enhancing youth sport programs to meet the unique developmental needs of children, making the programs athlete centered rather than adult centered so that they truly are all about the kids.

Part I. Youth Sport Basics

Chapter 1. Overview of Youth Sport

Types of Youth Sport

Patterns of Participation in Youth Sport

Barriers to Youth Sport Participation

Organizations That Support Youth Sport

Wrap Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 2. Evolution of Youth Sport

When and Why Was Sport Introduced Into Schools as an Extracurricular Activity?

How Did Nonschool Youth Sport Become So Popular?

What Does Title IX State, Why Was It Necessary, and How Did It Change Youth Sport?

How Did Little League Baseball Become So Popular?

Why Do Grassroots Youth Sport Programs Lack National Organization and Support?

How Have Changes in Parenting Philosophy and Practice Influenced the Evolution of Youth Sport, Particularly the Decline of Free Play?

Wrap-Up

Chapter 3. Philosophy and Objectives of Youth Sport

The POPP Sequence: From Philosophy to Action

What Should the Objectives of Youth Sport Be?

Tension Points in Youth Sport Philosophies and Objectives

Consequences of Developmentally Inappropriate Philosophies and Objectives

Palm Community Model of Youth Sport

Examples of Youth Sport Philosophies and POPP Sequences

Wrap Up

Learning Aids

Part II. Maturation and Readiness for Youth Sport Participation

Chapter 4. Physical Growth and Maturation

Growth

Maturation

Physical Growth and Maturational Influences on Sport Opportunities and Performance

Wrap Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 5. Readiness for Learning Skills and Competing

What Is Readiness?

The “Mountain” of Motor Skill Development

Sensitive Periods in Motor Skill Development

Cognitive Readiness

Is Earlier Better?

When Should Kids Start Organized Youth Sports?

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 6. Motivation and Psychosocial Development

Why Do Children Participate in Youth Sport?

Competence

Autonomy

Relatedness

Wrap Up: Provide Kids a Motivational FEAST

Learning Aids

Chapter 7. Modifying Sport for Youth

Why Should Sport Be Modified for Youth?

Why Do Adults Resist Youth Sport Modification?

What Changes Should Be Made?

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 8. Teaching Skills to Youth Athletes

The Five-Step Teaching Cycle

Instructional Strategies to Maximize Learning

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Part III. Intensity of Participation in Youth Sport

Chapter 9. Physical Training and Young Athletes

Positive Effects of Physical Activity and Training in Kids

Negative Effects of Over-Intensity in Physical Training in Youth

Physical Training Guidelines for Young Athletes

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 10. Talent Development in Sport

Talent Development Basics

How Is Talent Identified, and When Do We Decide Who Is Talented?

The Relative Influences of Practice and Innate Qualities on Sport Expertise

What’s the Best Way to Develop Sport Talent?

Specialization in Youth Sport

Categorizing Sports Based on Specialization Demands

Tips for Nurturing Talent and Well-Being in Youth Athletes

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 11. Stress and Burnout in Youth Sport

Stress as a Process

Demands (Stressors) Faced by Youth Athletes

Young Athletes’ Assessment of Demand(s)

Young Athletes’ Responses to Stress

Outcomes From the Stress Process

Flow: The Ultimate Goal for Youth Sport Participants

Burnout in Youth Sport

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 12. Injuries in Youth Sport

Youth Sport Injury Basics

Overuse Injuries

Physeal Injuries

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes

Concussion in Youth Sport

Legal Duties and the Emergency Action Plan

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Part IV. Social Considerations in Youth Sport

Chapter 13. Cultural Competence in Youth Sport

Continuum of Cultural Competence

Gender and Youth Sport

Reasons for Gender Differences in Youth Sport

Race and Ethnicity in Youth Sport

Sexual Orientation and Youth Sport

Disability and Youth Sport

Sexual Abuse in Youth Sport

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 14. Coaches and Youth Sport

Coaching Education and Certification

Recruiting Youth Sport Coaches

Evaluating Youth Sport Coaches

Building the Youth Sport Coaches’ Skill Set

Youth Sport Coaches’ Meta-Skill: Communication

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 15. Parents and Youth Sport

Foundations of the Parent-Child Relationship

Three Roles of Youth Sport Parents

WANTED: Positive Parent Behaviors in Youth Sport

Understanding Parent Traps

Parent Education in Youth Sport

Strategies for Coaches in Interacting with Youth Sport Parents

Suggestions to be a Better Youth Sport Parent

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Chapter 16. Moral and Life Skills Development in Youth Sport

Understanding Terms Related to Moral Behavior in Sport

How Sportsmanship and Moral Behavior Are Learned

Enhancing Sportsmanship, Moral Development, and Life Skills in Youth Athletes

Wrap-Up

Learning Aids

Robin S. Vealey, PhD, is a professor in the department of kinesiology and health at Miami University in Ohio, where she has worked for more than 30 years. She has dedicated nearly her entire adult life to youth sports, whether as a coach, administrator, educator, researcher, or consultant. She is internationally known for her research on the psychological aspects of youth sport and coaching effectiveness. Vealey, who has authored three books, has won several professional awards throughout her academic career, including being named a fellow by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) and the National Academy of Kinesiology. She previously was president of AASP, is a certified consultant in sport psychology as recognized by AASP, and is on the U.S. Olympic Committee Sport Psychology Registry. In addition to serving on numerous journal editorial review boards, Vealey is a past editor of The Sport Psychologist.

In 2011, Vealey was named to the Marshall University Athletic Hall of Fame after a stellar playing career in women’s basketball. Vealey went on to serve as a collegiate volleyball and women’s basketball coach and an athletics administrator. She currently enjoys playing golf and continues to remain active in various sports as a sport psychology consultant for youth athletes and teams.

Melissa A. Chase, PhD, is a professor in the department of kinesiology and health at Miami University in Ohio, where she has worked for two decades. She specializes in research about coaching efficacy and self-efficacy in children interested in increasing motivation and effectiveness, and she has presented her research across the United States and internationally. She was named a fellow by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) and SHAPE America and is a certified consultant in sport psychology as recognized by AASP. Chase was the founding editor of the Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, which is an official AASP publication.

Before becoming a professor, Chase gained experience as a physical education teacher at both the elementary and secondary school levels while coaching various levels of basketball, cross country, track and field, and volleyball for several years. She enjoys running and watching her teenage children participate in youth sports.

Specialization in Youth Sport

We’ve already learned that expert athletes tend to participate in many sports and activities, emphasizing deliberate play and enjoyment, until age 12. Generally, they begin to specialize, or narrow their focus, in one favored sport around age 13.

We've already learned that expert athletes tend to participate in many sports and activities, emphasizing deliberate play and enjoyment, until age 12. Generally, they begin to specialize, or narrow their focus, in one favored sport around age 13. So we know that early specialization is not required for expertise in most sports. However, many parents and coaches believe that there are still advantages to early sport specialization, so why not do it? And if athletes should specialize in their teen years, what does that mean? Should they drop out of all activities and do one sport to the exclusion of all other activities? How narrowly should they specialize? And, just because elite athletes have been shown to specialize in their teen years, does that mean that all youth athletes should follow that pathway?

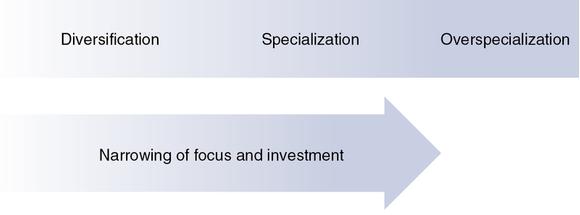

Specialization, Diversification, and Overspecialization

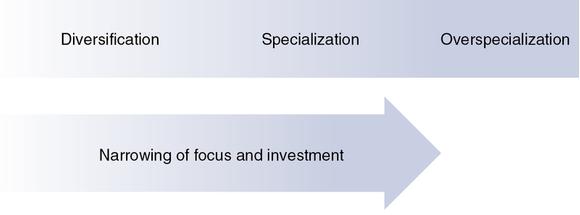

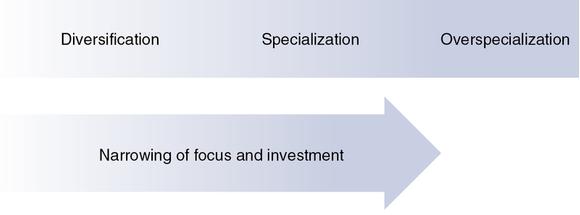

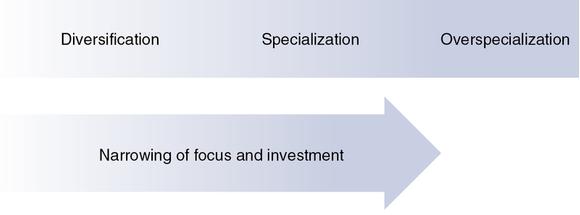

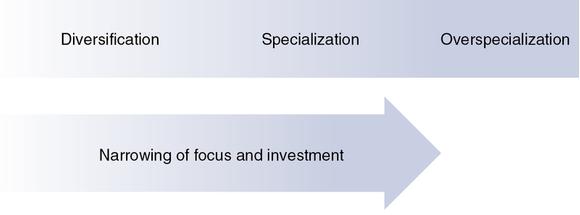

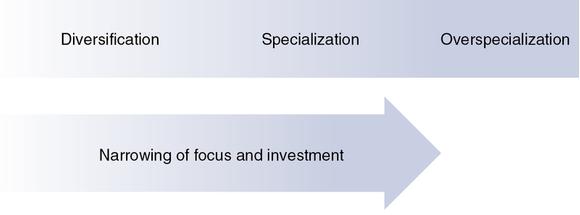

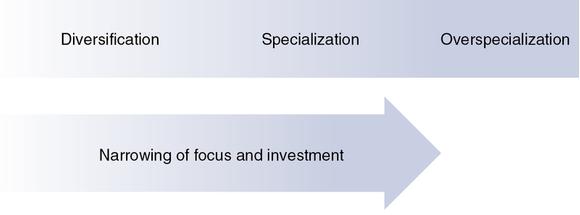

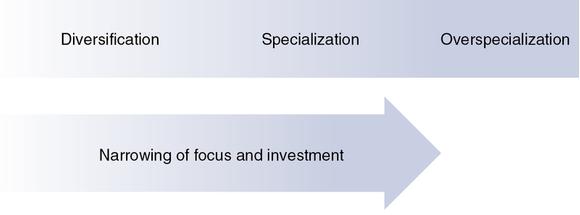

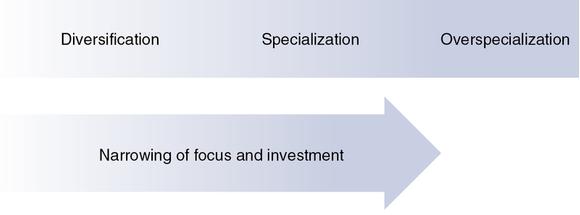

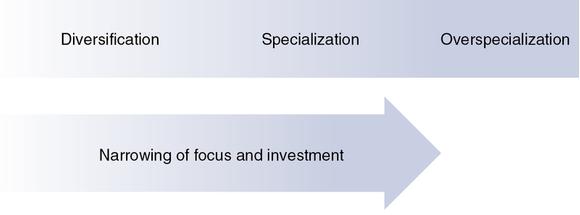

Specialization involves an investment in a single sport through systematic training and competition, typically including year-round participation in that sport, to pursue proficiency and enjoyment in a signature activity. The opposite of specialization is diversification, which is an investment in a broad range of sports and activities. Although we tend to view specialization and diversification dualistically, as categorical opposites, in reality they are on a continuum representing the degree to which athletes specialize or diversify (see figure 10.3).

Specialization continuum.

Degrees of Sport Specialization

Our daughter sampled soccer, tae kwon do, basketball, volleyball, and track (athletics) before age 14, at which time she chose to focus solely on volleyball. She participated in a fall school season, a spring club season, a summer camp season, and off-season conditioning in volleyball throughout high school. However, she also participated in the steel drum band, art club, and Academic Challenge team. So, you could say she "specialized" in volleyball, but she chose to participate in other activities. Some youth athletes have a signature sport that is their favorite, which they engage in year-round (often achieving awards and opportunities for higher-level participation) while also engaging in other sports in the off-season for enjoyment and cross-training.

So our definition of specialization emphasizes a narrowing of focus and main emphasis on one sport as a signature activity, with the possible continuation of some complementary or secondary activities. Research has shown that elite athletes narrowed their number of activities to focus on their main sport in the specializing years but remained involved in a couple of other sporting activities for relaxation and cross-training during the off-season (Baker et al., 2003).

However, a growing trend in the United States has been to push for exclusive specialization, in which athletes discontinue all other sports and most other extracurricular activities, to train and compete year-round in one sport. This is often mandated by coaches who, for some unfathomable reason, have the power to cut athletes from their programs unless the athletes agree to quit all other sports and most activities. For example, a high school soccer coach in our area required attendance at a summer-long conditioning program and refused to allow athletes to miss a workout to go on summer vacations (even for a week) with their families.

Exclusive specialization has contributed to the epidemic of overuse injuries emerging in the past two decades by depriving young athletes of the benefits of cross-training and off-season rest. So although specialization is not inherently bad, the narrow ways in which it is interpreted by overzealous coaches have created negative outcomes for youth athletes.

The Problem of Overspecialization

When the exclusivity or intensity of specialization is so great that children suffer adverse mental and physical health effects, it becomes overspecialization. Overspecialization occurs when children, often controlled by parents or coaches, pursue expertise and extrinsic rewards in one sport through year-round systematic training and competition, and sacrifice their psychological development and well-being as well as participation in most all other activities typical of kids their age. Unfortunately, examples of overspecialization are common in sport.

The title of former elite gymnast Jennifer Sey's (2008) book says it all: Chalked Up: Inside Elite Gymnastics' Merciless Coaching, Overzealous Parents, Eating Disorders, and Elusive Olympic Dreams. Dominique Moceanu was the youngest (age 14) member of the American gymnastics team who won the gold medal in team competition in the 1996 Olympic Games. Her book, Off Balance (2012), describes a sickening overspecialization experience of emotional and physical abuse, including the ignoring and ridiculing of injuries. In his autobiography Open, Andre Agassi (2009) describes the abuse that he endured from his father as a child: "No one ever asked me if I wanted to play tennis, let alone make it my life. . . . I hate tennis, hate it with all my heart, and still I keep playing because I have no choice. . . . I beg him for a chance to play [soccer with friends]. He shouts at the top of his lungs: ‘You're a tennis player! You're going to be number one in the world! You're going to make lots of money. That's the plan, and that's the end of it'" (pp. 27, 33, 57).

Emotional abuse has been documented across many youth sports (Gervis & Dunn, 2004; Kerr & Stirling, 2012; Stirling & Kerr, 2007). This form of abuse includes belittling, humiliation, threats, and denial of attention and support; and it goes beyond the strong communication and external regulation often used by coaches to push athletes in their training. Overspecialization involves adult behavior that crosses the line; the well-being of athletes is superseded by an obsession with attaining extrinsic rewards in sport (e.g., Olympic medals, college scholarships, or simply winning). This is called the rationalization of sport, whereby performance becomes more important than the human beings who are producing that performance (Donnelly, 1993). A swimming parent explains, "It was tough to see it [abuse] happening, but . . . once your kid starts winning championships it's easy to forget that she may be damaged along the way" (Kerr & Stirling, 2012, p. 201).

Water Break

The Marinovich Project

The Marinovich Project is a 2011 ESPN film about Todd Marinovich, raised by his father in a highly controlled environment with the goal of shaping Todd into the greatest football quarterback of all time. His father, Marv, stated, "The question I asked myself was, ‘How well could a kid develop if you provided him with the perfect environment?'" (Sagar, 2009). Marv put Todd through special stretching and flexibility exercises while he was still in the cradle. Todd ate only fresh-cooked strained vegetables as a baby and continued a special diet throughout his development. On nonschool days, he regularly completed 4-hour workouts, including fitness training, stretching, weightlifting, plyometrics, and throwing drills. He had a stable of scientific specialists honing his physiological, biomechanical, and mental skills throughout his youth.

Marinovich's talent and training led him to huge success in high school, where in 1987 he amassed a national-record 9,194 passing yards and was the National High School Player of the Year. He chose to play college football at the University of Southern California, and although he was successful, he was suspended from the team multiple times for rules transgressions. He signed with the National Football League Los Angeles Raiders, but was released after two years of professional football. After that, he was arrested for numerous drug violations, and for years he was a full-blown drug addict. Esquire referred to him as "the man who never was," stating, "You could say that Todd missed his childhood. Sports took away his first twenty years. Then drugs took the second twenty" (Sagar, 2009).

In the film, Marinovich talks about his personal discomfort with his upbringing, admitting he felt like a "freak show." In reflecting back about when he won the starting quarterback job with the Raiders, he stated, "I'd done what I wanted to do, [which was] please the old man. I'd accomplished all I wanted, and I was done." He admits that his drug use was an escape from the intensity of his overspecialized world. It is not our intent to denigrate Todd Marinovich, but rather to use his story as an example of the perils of overspecialization.

Summary of the Specialization Continuum

Overspecialization is specialization gone amuck, because it sacrifices the most important thing - the well-being of the athlete - for selfish adult motives. It should be avoided at all costs. Whether athletes choose to remain diversified or to specialize once they leave their early sampling years should be up to them.

There are athletes who choose to narrowly specialize in one sport because it is their passion, they enjoy it, and they choose to spend their time focusing on that sport. Professional Golfers' Association (PGA) star Rickie Fowler's mom recalls her son's devotion to golf: "When he was 7, he told me, ‘Mom, I don't want to play baseball or do gymnastics anymore. Just golf. I want to be a pro.' And he worked on it every day. He sacrificed his social life. No parties. No vacations. Didn't go to football games. I was a little worried back then. He actually allows himself a little bit more fun now. But either way, he loved it" (Diaz, 2014, p. 108). Earlier in the book, we offered similar stories about Rory McIlroy, Tiger Woods, Sidney Crosby, Serena Williams, and Chris Evert. Clearly, there are athletes who choose to specialize early because the sport is their passion. But the problem is that many adults see these examples and assume that early, exclusive specialization is the pathway for all kids to take. We forget that the passion and commitment must be inside of the young athletes, and the choice to specialize and train to the exclusion of most other pursuits is theirs.

Many teenagers choose to remain diverse and participate in many sports and activities. It's really an individual preference for the vast majority of youth sport participants who are not interested in pursuing expertise or elite status in sport. We have noticed that because the performance levels of youth sport continue to improve, it's getting more difficult to make high school sport teams. So some specialized commitment and focus on a sport may be necessary to continue participation at the high school or selective club levels. Athletes should decide for themselves whether and how much to specialize, with guidance and support (not mandates) from parents and coaches.

Merits of Early Diversification

The next issue to address is when, or how early, athletes should specialize in a sport. Most sport scientists and professional organizations advocate early (12 years and under) diversification as opposed to early specialization in sport (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000; National Association for Sport and Physical Education, 2010). In this section, we've identified several reasons why early diversification is a good idea for most children.

- Children can diversify early and still attain elite athlete status in most sports as an adult. As discussed previously in the chapter, elite athletes in a variety of sports have achieved elite sport status after engaging in early diversification (or sampling) in their childhood years (typically until around age 12) (Baker et al., 2003; Gulbin et al., 2010; MacNamara et al., 2010b; Soberlak & Cote, 2003). A study of over 4,000 Olympic athletes found that the average starting age in their chosen sports was 11.5 years (Gullich, 2007, as cited in Vaeyens et al., 2009). Overall, specialized training at an early age was not a prerequisite for reaching elite levels across a range of Olympic sports. A study of 708 minor league professional baseball players showed that although their mean starting age was 6 years, the players' mean age of specializing in baseball was 15 years (Ginsburg et al., 2014). The majority of players (52%) did not specialize until at least 17 years of age. Most sports, like the ones in these studies, are considered late-specialization sports, in which exclusive specialization and extensive deliberate practice are not necessary before age 12.

On the other hand, gymnastics and figure skating have been designated early-specialization sports (Balyi et al., 2013; Vaeyens et al., 2009), in which elite levels of performance are achieved before puberty. Gymnastics and figure skating are subjectively judged, with performance expectations calling for smaller, lighter, more flexible bodies to execute the difficult skills required at the elite level. Thus, it is typical for gymnasts and skaters who aspire to attain elite status to begin extensive technical training very early, and there is evidence that expert athletes specialized earlier than nonexpert athletes in these sports (O'Connor, 2011). Former Olympian Dominique Moceanu began gymnastics at age 3, and by age 7 she was training six days a week for at least 25 hours per week.

Overall, research supports early diversification as facilitative to athletes' development in most sports. Kids can start their favorite sports early and also participate in other sports and activities. Early diversification doesn't mean that a young athlete can't spend a significant amount of time doing the sport he likes best. We would just recommend that early experiences in the late-specialization sports include a lot of deliberate play and spontaneous practice, as opposed to excessive levels of highly technical deliberate practice. - Early diversification develops a broad range of fundamental motor skills and different sport experiences that provide the athlete with more performance options and athleticism if they choose to specialize in one sport later. A youth baseball academy coach discusses highly specialized athletes who can perform the mechanics of their sport but lack well-rounded motor skills: "My God, this kid is a horrible athlete. He can't run. He can't move. He's spent all his time in the batting cage. So many of these kids have played no other sport. They're one-trick ponies" (Sokolove, 2008, p. 204).

David Leadbetter, internationally recognized golf instructor, coaches Charles Howell III, a PGA tour player who has not yet realized the great promise he showed as a junior golfer. Leadbetter says of Howell (whom he has coached from the age of 12): "Charles has had a solid career, but he hasn't hit the heights some thought he might. I have always felt part of his problem is that he played only golf growing up. That hurts him. In other ball games you develop a feel for throwing and distance. But Charles never did that. He doesn't have the instinctive touch or hand - eye coordination you need to hit the ball close [inside 120 yards, or 110 meters]. If only he'd played baseball as a kid. That would have helped his awareness for distance (Huggan, 2013, p. 37). - Early specialization has been linked to dropping out of sport. Ice hockey players who dropped out of their sport began off-ice training at a younger age and invested more hours per year in training at ages 12 and 13 as compared to active players (Wall & Cote, 2007). Both the dropout and active players enjoyed a diverse and playful introduction to sport, but the earlier specialized activities of the dropout players may have affected their motivation to continue in the sport.

A similar pattern was found in swimming (Fraser-Thomas, Cote, & Deakin, 2008a). Adolescent swimmers who dropped out were involved in fewer extracurricular activities and less unstructured swimming play during their early years, and also began more specialized training activities (training camps, dryland training) earlier than active swimmers. So although the starting ages of the dropout and active swimmers did not differ, the earlier specialized focus of the dropouts may have contributed to their discontinuation of swimming. Interestingly, dropout swimmers also reached "top in club" status earlier than active swimmers. The authors suggest that a comedown from child stardom to adolescent mediocrity, with resultant disappointment and decreased confidence, could occur for some kids who specialize and achieve early success.

Because dropping out is a motivational issue, it may be that early exclusive sport specialization does not allow youth athletes to experience the playful enjoyment found to be important to elite athlete development before age 12 (Bloom, 1985; Cote et al., 2003). A premature emphasis on technical training, deliberate practice, and competition may thwart the falling in love with a sport, which has repeatedly been shown to fuel the passion and commitment needed to continue to higher levels of sport. - Early specialization has been linked to burning out of sport. Another negative consequence that has been associated with early sport specialization is burnout. Discussed more fully in chapter 11, burnout occurs when a previously enjoyable activity becomes drudgery, so that athletes feel physically and emotionally exhausted. Adolescent athletes specializing in swimming, diving, and gymnastics were higher in emotional exhaustion (burnout) when compared to more diversified adolescent athletes who participated in a variety of activities (Strachan, Cote, & Deakin, 2009). A sole focus on tennis at a young age has also been linked to burnout (and dropout) in elite tennis players (Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996).

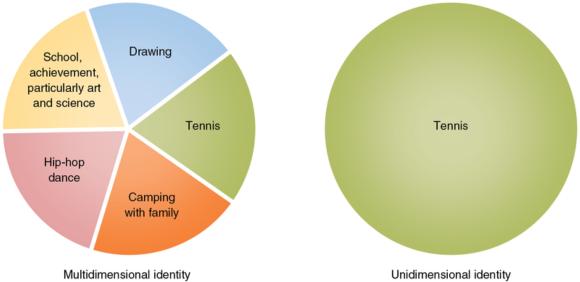

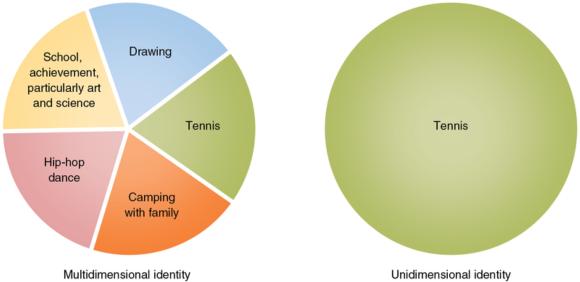

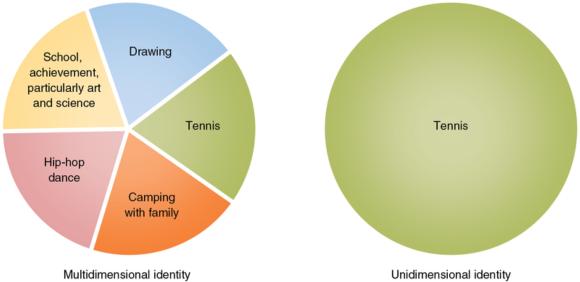

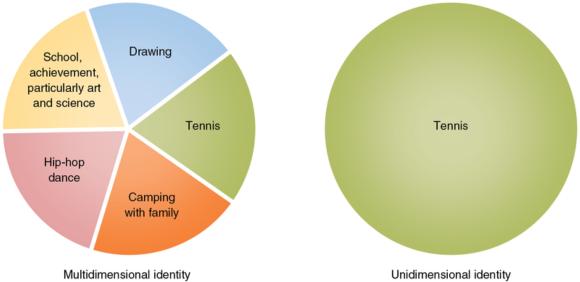

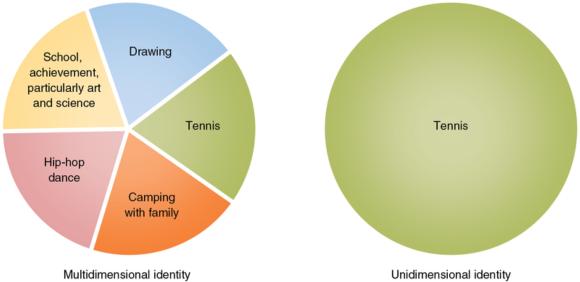

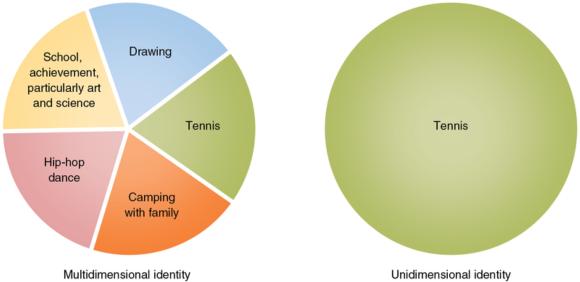

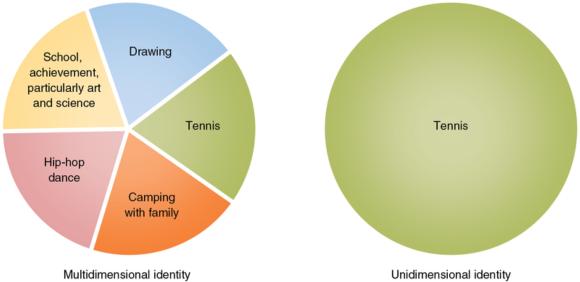

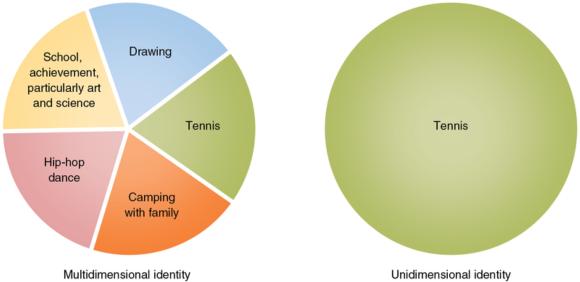

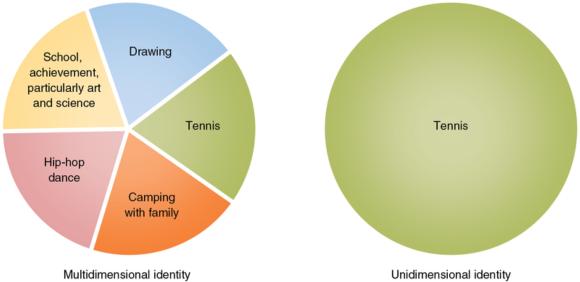

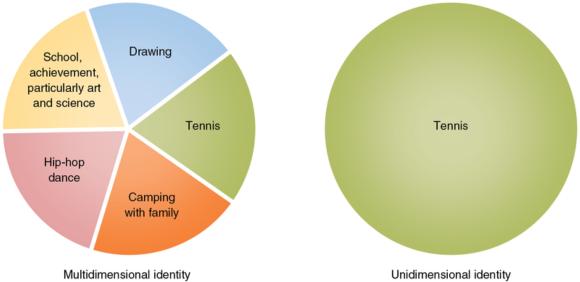

- Early diversification helps kids develop multidimensionality, or multiple pieces in their identity pie. The development of a multidimensional identity, or self-concept, is important for the mental health and well-being of children. Exclusive specialization at a young age can restrict children to a unidimensional self-concept, which has been linked to burnout and psychological dysfunction (Coakley, 1992). Adolescent athletes who were engaged in other activities (e.g., performing arts, school, church) along with their sport participation have been shown to possess healthier psychological profiles than adolescents who participated only in sport (Zarrett et al., 2008).

A useful activity to do with young athletes is to ask them to draw their personal identity pie, labeling various pieces of the pie to represent who they are. The pie on the left side of figure 10.4 provides a multidimensional example: A young tennis player identifies other personally significant activities or personal strengths that define who she is. The pie on the right side of figure 10.4 might be drawn by another young tennis player; she is narrowly unidimensional and would be vulnerable to major blows to her self-worth and self-concept when encountering obstacles in her pursuit of expertise in tennis. A multidimensional identity is a good insurance policy for kids because it provides them with broad coverage of their sense of self. Help young athletes develop lots of pieces in their pies.

Multidimensional versus unidimensional identity pie.

Structural Strategies to Avoid Overspecialization and Exclusive Specialization

To quell the rising tide of professionalization, overspecialization, and exclusive early specialization, policies and regulations should be instituted at the organizational level. "Developmentalizing" should always trump professionalizing when it comes to youth sport. Two examples are provided here, and we encourage you to consider additional ways to protect the interests of young athletes.

- Continue and expand the practice of implementing minimal age restrictions for athletes to compete in professional or international sport. The minimal age to compete internationally in gymnastics rose from 14 years before 1981, to 15 years in 1981, to 16 years in 1997 (one is eligible if one achieves the minimal age sometime in the Olympic or competition year). The age restriction is designed to protect child athletes from injury and exploitation, although it remains controversial, often with accusations of age falsification for international events. Professional tennis has a minimum age requirement of 14 years. The National Basketball Association requires draftees to be 19 years and one year removed from high school graduation, while prospects may be drafted right out of high school for Major League Baseball.

These restrictions are important because they have a trickle-down effect on youth sport. When Kevin Garnett signed as the fifth pick in the National Basketball Association draft in 1995 straight out of high school, the search for star players moved down from high school to elementary school (Dohrmann, 2010). It fueled the pressure on kids to play year-round and travel extensively at extremely young ages to compete in national tournaments. For example, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) has sponsored a 2nd-grade boys' national championship tournament since 2004. Sport organizations and youth sport leaders should continue to lobby for age restrictions to protect kids from pressure to specialize early and exclusively. - No athlete should be restricted from diversification through high school participation. This recommendation is designed to preserve young athletes' rights to diversify their sport participation through their high school years. Others have recommended 15 years as the cutoff age for protected diversification (Wiersma, 2000), and we agree that this is a logical age cutoff. However, we see no reason that adults should mandate specialization before college when 98% of high school athletes are not going on to play at the collegiate level. Coaches and parents should guide young athletes in making important decisions about multiple sport participation versus more specialized approaches. But this should be discussed on an individual-case basis and should ultimately be the athlete's decision. We urge athletic directors and state and national high school sport associations to develop regulations that prevent coaches from having the power to restrict athletes' activities.

Save

Learn more about Best Practice for Youth Sport.

Burnout in Youth Sport

I don’t know, Mom, I just feel burned out. As a parent, what would you do if you heard this? We all have a vague understanding of burnout, but should we advise our kids to drop out, take a break, make some changes, or suck it up?

"I don't know, Mom, I just feel burned out." As a parent, what would you do if you heard this? We all have a vague understanding of burnout, but should we advise our kids to drop out, take a break, make some changes, or suck it up? Because burnout is a popular term, we need to carefully consider what is true and not true about burnout in youth athletes.

What Is Burnout?

Burnout is a negative psychological and physical state in which young athletes feel tired, less able to perform well, and less interested in playing their sports. Three symptoms characterize burnout.

Physical and Emotional Exhaustion

Although it is common for athletes to get tired after training sessions or competitions, the exhaustion associated with burnout involves the depletion of emotional and physical resources beyond the typical tiredness that comes and goes throughout a sport season. Parents may notice kids feeling too tired to do things outside their sport, feeling emotionally drained and lethargic, and wanting to take a break from sport.

Reduced Sport Accomplishment

The second symptom can be a lack of performance success or inconsistent performance, or it can be more about the perception on the part of the athlete that she is not playing up to her potential. The athlete may feel that she's not getting anywhere - for example, not improving or moving forward.

Devaluation of Sport

Devaluation means a reduction in value: The athlete doesn't care as much about his sport. Athletes may say "I'm sick of doing this"; "I don't care about playing anymore"; or "It's just not fun anymore." Another common symptom is questioning things - for example, "Why am I doing this?"

How Prevalent Is Burnout in Youth Sport?

Many popular media stories warn of an impending burnout epidemic in youth sport. However, research has identified only a very small percentage (1-2%) of adolescent athletes who have experienced severe burnout. It is true, though, that the majority of youth athletes surveyed admitted to having experienced low to moderate levels of burnout (Gustafsson, Kentta, Hassmen, & Lundqvist, 2007; Raedeke & Smith, 2004). Athletes report more burnout as they increase in age from 7 to 17 years (Harris & Watson, 2014).

What Causes Burnout in Youth Athletes?

Several factors contribute to burnout in youth athletes. We've categorized them into three groups: overload factors, social climate factors, and personality factors (see table 11.1).

Overload Factors

Overload factors represent what people usually think about when they hear that someone is burned out. Previously in this chapter, you learned that overstress involves demand that exceeds athletes' abilities to cope, such as when they are overloaded without adequate physical and mental recovery. As discussed in chapter 9, overtraining is the result of excessive training and inadequate recovery, which typically leads to decreased performance and psychological distress (Richardson, Andersen, & Morris, 2008). The difficulty for coaches is determining how much overload (an essential, useful aspect of sport training) is appropriate for their athletes. Some overload is needed to induce a training effect and improved performance, but too much overload without adequate recovery results in decreased performance (called staleness), exhaustion, decreased interest in training, and negative moods (burnout). To clarify, staleness is the term typically used to describe impaired performance as the result of overtraining; burnout is a broader concept that focuses on psychological distress and decreased motivation in a previously enjoyed activity (Kentta & Hassmen, 1998) as a result of overload without adequate recovery.

Social Climate Factors

Social climate contributors to burnout are those negative aspects of the youth sport culture that are harmful to the psychological development and well-being of kids. These include pressure from parents to perform or achieve certain outcomes (e.g., winning, making the varsity team, gaining a college scholarship) and negative coaching behaviors, such as extreme controlling behaviors and developmentally inappropriate training and performance expectations. Athletes who feel trapped in their sport participation tend to be higher in burnout than athletes who were personally invested in and enthusiastic about swimming (Raedeke, 1997). This occurs when athletes do not really want to participate but feel they have to maintain their involvement in sport based on social pressure from others.

It has been argued that burnout is not a response to stress but rather a response to the social climate of highly organized youth sport, in which young athletes are highly controlled and inhibited in their identity development (Coakley, 1992). According to this perspective, stress is a symptom of burnout, but not the cause. Interviews with 15 elite youth swimmers who experienced burnout indicated that these athletes became powerless to control what was happening in their lives and their personal development. The result of this highly controlling, overstructured quality of youth sport was burnout. This explanation for burnout is important because it identifies the roots of burnout as the youth sport culture, as opposed to some personal failure or lack of competence (e.g., toughness) in young athletes.

Personality Factors

Although the structure of youth sport and the behavior of coaches and parents are critical in influencing burnout, several personality factors have been related to burnout in youth athletes. Trait anxiety and weak coping skills are obvious factors, based on their importance in the stress process discussed previously. Negative perfectionism (Hill, 2013) and obsessive passion (Martin & Horn, 2013) are examples of personality factors that create extreme aspirations and irrational needs (inability to accept mistakes, inflexible goals, compelling pressure to participate) in relation to one's sport participation. Interestingly, positive or adaptive perfectionism (high standards, organizational skill, achievement orientation) and harmonious passion (loving one's sport without feeling controlled by it) is related to lower levels of burnout. Unidimensional identity, also related to burnout, was identified in chapter 10 as a dangerous narrowing of a child's self-concept based on overexclusive specialization in sport. Youth sport athletes should protect themselves from burnout by engaging in different types of activities to define themselves in multidimensional ways.

Personal Plug-In

Have You Been Burned Out?

Did you ever experience burnout as a youth athlete? Describe how it felt: Were all three burnout symptoms present? Consider the specific factors that led to this experience of burnout for you. Why do you think it happened? How did it affect your sport experience, particularly your motivation and choices about staying in sport?

Strategies to Help Athletes Avoid and Deal With Burnout

- Although definitiveness is lacking, it is thought that physical and emotional exhaustion serves as a first indicator of developing burnout in young athletes. Observing these symptoms should prompt adult coaches and parents to intervene immediately and work with the athlete to find the best strategy to ensure some rest, recovery, and mental rejuvenation.

- Identify athletes whose personalities or life situations predispose them to burnout, and make it a point to intervene with guidance and suggestions to help them achieve without crossing the line into harmful training behaviors. One recommendation is to identify a sport psychology consultant who can work with youth athletes to enhance their mental approaches to competition. Gaining perspective and developing skills to move from negative types of passion and perfectionism toward more adaptive forms of these characteristics would be useful.

- Anyone (parent or coach) can help young athletes learn active coping skills. Better lifestyle management, healthier decisions, more rational perspectives on competition, and skill in identifying and pursuing personal mastery goals are all coping skills that can be learned by young athletes.

- Guide young people in adopting multiple areas of interest and achievement. Such variety and multidimensionality guard against burnout that occurs from a single-minded obsession gone awry.

- Listen to your kids, and clarify whether they want to continue in a sport. This is difficult for parents, especially when they observe the special talent a young athlete has in a particular sport only to see him decide to give it up. Although we agree that parents have an initial role in getting kids to try different sports, it doesn't work for athletes to feel compelled to stay in a sport only because of their parents.

- Parents know best the vast array of stressors operating in a young athlete's life, so it's up to parents to hold the line in staking out recovery time for their children (often despite coaches' and the young athletes' protests). Someone has to be in charge and protect the health and well-being of the athletes, particularly since they're young.

- Lead the charge for developmentally appropriate practice in youth sport. The excessive control and exploitation of youth athletes to pursue adult-mandated goals such as early specialization, as well as an emphasis on winning over athlete development, lead to burnout and dropping out. Follow the guidelines in the long-term athlete development model (Balyi, Way, & Higgs, 2013) presented in chapter 5 so that the emphasis is on a progressive development of skills, a gradual introduction to competition, a focus on enjoyment and the nurturing of motivation, and a lifelong commitment to physical activity.

Save

Save

Learn more about Best Practice for Youth Sport.

Reasons for Gender Differences in Youth Sport

Average gender differences in sport and motor skills may be attributed to physical - biological differences, as well as the differential socialization of boys and girls in our society.

Average gender differences in sport and motor skills may be attributed to physical - biological differences, as well as the differential socialization of boys and girls in our society.

Physical and Biological Differences

Several physical characteristics of postpubescent males predispose them to outperform females in sports that require strength, power, and speed. Adult males tend to be taller with longer limbs. The breadth of their shoulders allows for more muscle on a larger shoulder girdle, the main contributor to postpubescent males' advantage in upper-body strength. Adult males have more overall muscle mass and less body fat than females, even in trained samples. Male athletes average 4% to 12% body fat compared to 12% to 23% in female athletes. Males develop larger skeletal muscles, as well as larger hearts and lungs and a greater number of red blood cells (which absorb oxygen for an aerobic advantage). Without question, males and females differ on several physical characteristics that influence sport performance. But what about the gender differences that appear before puberty, when the physical differences between males and females are still very small?

Gender Stereotyping

The answer lies in how girls and boys in our culture learn about and internalize gendered beliefs, values, and practices. This is called socialization, a process in which we actively formulate ideas about who we are and how we're supposed to act (and not act). Males and females are socialized very differently in most cultures. As a result of this socialization, stereotypes are often formed. A stereotype is a popular belief about specific types of individuals in certain categories.

Gender stereotyping is a process in which children's biological sex determines the activities they engage in (and not engage in), as well as the manner in which they are treated in these activities. Sports are generally considered a masculine domain, and this stereotype results in boys' perceiving greater ability and attaching greater importance to sport than girls. This contributes to the gender differences observed in sport. Following are some specific examples of gender stereotyping.

- Females have not been as encouraged by parents to be physically active. Parents have been shown to provide less encouragement for physical activity, offer fewer sport-related opportunities for their daughters than for their sons, and perceive their sons to have higher sport competence than their daughters (Fredricks & Eccles, 2005).

- Females are less apt to be taught and to engage in fundamental motor skills during sensitive periods. In chapter 5, you learned that the sensitive period for learning fundamental motor skills is between the ages of 2 and 8 years in children. This is the limited time in human development when the effects of learning experiences on the brain are particularly strong. Sensitive periods are the most fertile time to learn motor skills; and although skills may be acquired later, it is much more difficult, and typically athletes fail to reach the same levels of proficiency as those who began acquiring them during their sensitive period. On average, boys are superior to girls on most fundamental motor skills, particularly object control (throwing, catching, kicking) and body control (agility) skills.

When females fail to develop these critical fundamental skills during their early years, they are disadvantaged later when they wish to participate in sport. It may be a lack of opportunity or instruction or peer socialization that blocks girls from participation. An example of peer socialization is boys' derogatory remarks to girls about sport involvement. Here is a sample of comments made by boys about girls playing sports with them on the playground: "Girls are too weak," "They are girly-girls," "It's a man's game," and "They're too weak, fragile, short, and they might break a nail" (Oliver & Hamzeh, 2010). Just make some simple observations at your local pool, park, or playground, and we bet you'll notice differences in how children play and engage in fundamental motor skills. Boys' play tends to be more active and sport related, whereas girls' play often is more passive, physically restricted, and quiet. - Gender-stereotypical toys have been emphasized throughout childhood and adolescence. See the Water Break section for a discussion of this topic.

- Youth are often pressured into "gender-appropriate" sports. If someone tells you that she has a child playing ice hockey and another doing figure skating, what assumption do you typically make about these kids? The gendered assumption would be that a boy plays ice hockey and a girl figure skates. Kids do gender-type sports as more or less appropriate (e.g., gymnastics for girls because they're flexible and it's a girls' sport, football for boys because it is rough with lots of contact) (Hannon, Soohoo, Reel, & Ratliffe, 2009).

- Female athletes are constantly sexualized by the media. Sexualization occurs when people value a girl or woman primarily for her sexual appeal and view her as an object for sexual use. Male athletes are rarely depicted as sexual objects when they endorse a product or are on a magazine cover, while female athletes are most often shown in sexualized poses as opposed to a sport action photo. Sexualization of girls begins at puberty, which is a big reason their self-esteem drops during this period. Sexualization leads to depression, bodily shame, low self-esteem, and disordered eating in females. When high school and college females observed pictures of female athletes actively engaged in their sports, their feelings about their physical abilities increased and they were more motivated to be physically active (Daniels, 2009). When they viewed pictures of female athletes in sexualized poses, girls felt more negativity about their own physical appearance and body image. Media depictions of sexualized athletes directly counteract all the positive benefits that sport participation brings to young girls.

- Boys who are not physically skilled or good athletes experience ridicule and embarrassment, based on the rigid male stereotype that includes strength, muscularity, athleticism, and lack of empathy for other participants (Tischler & McCaughtry, 2011). Boys who are good at sports are often popular among peers, with enhanced self-esteem and self-image and positive identity. The ridicule experienced by boys who don't fit the culturally prescribed gender role may cause them to struggle with self-esteem and social relationships. Boys who didn't meet the prescribed masculine athlete stereotype have explained the negative effects (Tischler & McCaughtry, 2011): "Sometimes I am so nervous about the [sport] activities that I feel sick. One time I threw up because I was so nervous about doing this . . . and I'm not good at it. I did not want the other kids to see me" (p. 43). "People make fun of you . . . and if you screw up the other kids yell and scream at you and make fun of you" (p. 44).

Why Does Gender Stereotyping Occur With Kids?

Many parents explain their gender-stereotypical parenting practices as coming from a desire for their kids to fit in and be accepted in the culture. Yet, children and adolescents need to be educated about harmful gender stereotypes that have been limiting and destructive to both females and males in sport. The use of derogatory terms such as tomboy, dyke, and fag indicates that a big part of gender stereotyping is the result of homophobia, which is an irrational fear or intolerance of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people. However, toys that parents buy and activities they herd their children into are not going to make the difference in the child's sexual orientation. Finally, gender stereotyping preserves the dominant social position of males and subordinate position of females in sport, which many people in society would like to continue. We think there's room for girls in sport, boys in sport, and boys and girls together in sport, in all kinds of sports - and that our culture is enriched because of it.

Moving Beyond Gender Stereotypes

So how would you respond to the young male wrestler who refuses to wrestle against a female (described at the beginning of the chapter)? You could tell him that girls' wrestling is one of the fastest-growing high school sports in the United States and that it is also an Olympic sport for females. You could ask him to describe the feelings and thoughts that are making the situation difficult for him, and help him move from sexualizing his opponent based on her being female to viewing her simply as another competitor.

We hope that adult leaders will not ignore tired sexist comments such as "You throw like a girl"; "Boys will be boys"; and "Bros before hos." Such statements are unacceptable and damaging to everyone. When the 3rd-grade teachers at New Roads School in Santa Monica, California, heard their students say "You throw like a girl," they presented their class with a short documentary on Mo'ne Davis. Davis was the first female pitcher to earn a win and to pitch a shutout in the Little League World Series (2014), with a 70-mile-per-hour (113 kilometers per hour) fastball and a curve that froze batters in their cleats. In her team's 4-0 victory over Nashville, she pitched six innings, struck out eight, and gave up two infield hits. She made the cover of Sports Illustrat ed and inspired young girls to go beyond rigid boundaries of gender-appropriate sports. Students from the school wrote Mo'ne about her impact, one saying, "Dear Mo'ne - I saw your video. I thought it was so cool because it gave me the feeling that I can do anything I put my mind to" (Chen, 2014, p. 152).

Invite competent females as coaches, and change the stereotypical assigning of menial duties to "team moms" to moms and dads (and change the name to "team manager"). Provide opportunities and expectations for girls to be active and part of any and all sports (and have them dress in comfortable clothes and sneakers so they can actively run and climb and jump to build fundamental motor skills). Provide support and counsel for young boys who don't fit the male athletic stereotype, and help them find outlets through which they can remain physically active.

Learn more about Best Practice for Youth Sport.

Specialization in Youth Sport

We’ve already learned that expert athletes tend to participate in many sports and activities, emphasizing deliberate play and enjoyment, until age 12. Generally, they begin to specialize, or narrow their focus, in one favored sport around age 13.

We've already learned that expert athletes tend to participate in many sports and activities, emphasizing deliberate play and enjoyment, until age 12. Generally, they begin to specialize, or narrow their focus, in one favored sport around age 13. So we know that early specialization is not required for expertise in most sports. However, many parents and coaches believe that there are still advantages to early sport specialization, so why not do it? And if athletes should specialize in their teen years, what does that mean? Should they drop out of all activities and do one sport to the exclusion of all other activities? How narrowly should they specialize? And, just because elite athletes have been shown to specialize in their teen years, does that mean that all youth athletes should follow that pathway?

Specialization, Diversification, and Overspecialization

Specialization involves an investment in a single sport through systematic training and competition, typically including year-round participation in that sport, to pursue proficiency and enjoyment in a signature activity. The opposite of specialization is diversification, which is an investment in a broad range of sports and activities. Although we tend to view specialization and diversification dualistically, as categorical opposites, in reality they are on a continuum representing the degree to which athletes specialize or diversify (see figure 10.3).

Specialization continuum.

Degrees of Sport Specialization

Our daughter sampled soccer, tae kwon do, basketball, volleyball, and track (athletics) before age 14, at which time she chose to focus solely on volleyball. She participated in a fall school season, a spring club season, a summer camp season, and off-season conditioning in volleyball throughout high school. However, she also participated in the steel drum band, art club, and Academic Challenge team. So, you could say she "specialized" in volleyball, but she chose to participate in other activities. Some youth athletes have a signature sport that is their favorite, which they engage in year-round (often achieving awards and opportunities for higher-level participation) while also engaging in other sports in the off-season for enjoyment and cross-training.

So our definition of specialization emphasizes a narrowing of focus and main emphasis on one sport as a signature activity, with the possible continuation of some complementary or secondary activities. Research has shown that elite athletes narrowed their number of activities to focus on their main sport in the specializing years but remained involved in a couple of other sporting activities for relaxation and cross-training during the off-season (Baker et al., 2003).

However, a growing trend in the United States has been to push for exclusive specialization, in which athletes discontinue all other sports and most other extracurricular activities, to train and compete year-round in one sport. This is often mandated by coaches who, for some unfathomable reason, have the power to cut athletes from their programs unless the athletes agree to quit all other sports and most activities. For example, a high school soccer coach in our area required attendance at a summer-long conditioning program and refused to allow athletes to miss a workout to go on summer vacations (even for a week) with their families.

Exclusive specialization has contributed to the epidemic of overuse injuries emerging in the past two decades by depriving young athletes of the benefits of cross-training and off-season rest. So although specialization is not inherently bad, the narrow ways in which it is interpreted by overzealous coaches have created negative outcomes for youth athletes.

The Problem of Overspecialization

When the exclusivity or intensity of specialization is so great that children suffer adverse mental and physical health effects, it becomes overspecialization. Overspecialization occurs when children, often controlled by parents or coaches, pursue expertise and extrinsic rewards in one sport through year-round systematic training and competition, and sacrifice their psychological development and well-being as well as participation in most all other activities typical of kids their age. Unfortunately, examples of overspecialization are common in sport.

The title of former elite gymnast Jennifer Sey's (2008) book says it all: Chalked Up: Inside Elite Gymnastics' Merciless Coaching, Overzealous Parents, Eating Disorders, and Elusive Olympic Dreams. Dominique Moceanu was the youngest (age 14) member of the American gymnastics team who won the gold medal in team competition in the 1996 Olympic Games. Her book, Off Balance (2012), describes a sickening overspecialization experience of emotional and physical abuse, including the ignoring and ridiculing of injuries. In his autobiography Open, Andre Agassi (2009) describes the abuse that he endured from his father as a child: "No one ever asked me if I wanted to play tennis, let alone make it my life. . . . I hate tennis, hate it with all my heart, and still I keep playing because I have no choice. . . . I beg him for a chance to play [soccer with friends]. He shouts at the top of his lungs: ‘You're a tennis player! You're going to be number one in the world! You're going to make lots of money. That's the plan, and that's the end of it'" (pp. 27, 33, 57).

Emotional abuse has been documented across many youth sports (Gervis & Dunn, 2004; Kerr & Stirling, 2012; Stirling & Kerr, 2007). This form of abuse includes belittling, humiliation, threats, and denial of attention and support; and it goes beyond the strong communication and external regulation often used by coaches to push athletes in their training. Overspecialization involves adult behavior that crosses the line; the well-being of athletes is superseded by an obsession with attaining extrinsic rewards in sport (e.g., Olympic medals, college scholarships, or simply winning). This is called the rationalization of sport, whereby performance becomes more important than the human beings who are producing that performance (Donnelly, 1993). A swimming parent explains, "It was tough to see it [abuse] happening, but . . . once your kid starts winning championships it's easy to forget that she may be damaged along the way" (Kerr & Stirling, 2012, p. 201).

Water Break

The Marinovich Project

The Marinovich Project is a 2011 ESPN film about Todd Marinovich, raised by his father in a highly controlled environment with the goal of shaping Todd into the greatest football quarterback of all time. His father, Marv, stated, "The question I asked myself was, ‘How well could a kid develop if you provided him with the perfect environment?'" (Sagar, 2009). Marv put Todd through special stretching and flexibility exercises while he was still in the cradle. Todd ate only fresh-cooked strained vegetables as a baby and continued a special diet throughout his development. On nonschool days, he regularly completed 4-hour workouts, including fitness training, stretching, weightlifting, plyometrics, and throwing drills. He had a stable of scientific specialists honing his physiological, biomechanical, and mental skills throughout his youth.

Marinovich's talent and training led him to huge success in high school, where in 1987 he amassed a national-record 9,194 passing yards and was the National High School Player of the Year. He chose to play college football at the University of Southern California, and although he was successful, he was suspended from the team multiple times for rules transgressions. He signed with the National Football League Los Angeles Raiders, but was released after two years of professional football. After that, he was arrested for numerous drug violations, and for years he was a full-blown drug addict. Esquire referred to him as "the man who never was," stating, "You could say that Todd missed his childhood. Sports took away his first twenty years. Then drugs took the second twenty" (Sagar, 2009).

In the film, Marinovich talks about his personal discomfort with his upbringing, admitting he felt like a "freak show." In reflecting back about when he won the starting quarterback job with the Raiders, he stated, "I'd done what I wanted to do, [which was] please the old man. I'd accomplished all I wanted, and I was done." He admits that his drug use was an escape from the intensity of his overspecialized world. It is not our intent to denigrate Todd Marinovich, but rather to use his story as an example of the perils of overspecialization.

Summary of the Specialization Continuum

Overspecialization is specialization gone amuck, because it sacrifices the most important thing - the well-being of the athlete - for selfish adult motives. It should be avoided at all costs. Whether athletes choose to remain diversified or to specialize once they leave their early sampling years should be up to them.

There are athletes who choose to narrowly specialize in one sport because it is their passion, they enjoy it, and they choose to spend their time focusing on that sport. Professional Golfers' Association (PGA) star Rickie Fowler's mom recalls her son's devotion to golf: "When he was 7, he told me, ‘Mom, I don't want to play baseball or do gymnastics anymore. Just golf. I want to be a pro.' And he worked on it every day. He sacrificed his social life. No parties. No vacations. Didn't go to football games. I was a little worried back then. He actually allows himself a little bit more fun now. But either way, he loved it" (Diaz, 2014, p. 108). Earlier in the book, we offered similar stories about Rory McIlroy, Tiger Woods, Sidney Crosby, Serena Williams, and Chris Evert. Clearly, there are athletes who choose to specialize early because the sport is their passion. But the problem is that many adults see these examples and assume that early, exclusive specialization is the pathway for all kids to take. We forget that the passion and commitment must be inside of the young athletes, and the choice to specialize and train to the exclusion of most other pursuits is theirs.

Many teenagers choose to remain diverse and participate in many sports and activities. It's really an individual preference for the vast majority of youth sport participants who are not interested in pursuing expertise or elite status in sport. We have noticed that because the performance levels of youth sport continue to improve, it's getting more difficult to make high school sport teams. So some specialized commitment and focus on a sport may be necessary to continue participation at the high school or selective club levels. Athletes should decide for themselves whether and how much to specialize, with guidance and support (not mandates) from parents and coaches.

Merits of Early Diversification

The next issue to address is when, or how early, athletes should specialize in a sport. Most sport scientists and professional organizations advocate early (12 years and under) diversification as opposed to early specialization in sport (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000; National Association for Sport and Physical Education, 2010). In this section, we've identified several reasons why early diversification is a good idea for most children.

- Children can diversify early and still attain elite athlete status in most sports as an adult. As discussed previously in the chapter, elite athletes in a variety of sports have achieved elite sport status after engaging in early diversification (or sampling) in their childhood years (typically until around age 12) (Baker et al., 2003; Gulbin et al., 2010; MacNamara et al., 2010b; Soberlak & Cote, 2003). A study of over 4,000 Olympic athletes found that the average starting age in their chosen sports was 11.5 years (Gullich, 2007, as cited in Vaeyens et al., 2009). Overall, specialized training at an early age was not a prerequisite for reaching elite levels across a range of Olympic sports. A study of 708 minor league professional baseball players showed that although their mean starting age was 6 years, the players' mean age of specializing in baseball was 15 years (Ginsburg et al., 2014). The majority of players (52%) did not specialize until at least 17 years of age. Most sports, like the ones in these studies, are considered late-specialization sports, in which exclusive specialization and extensive deliberate practice are not necessary before age 12.

On the other hand, gymnastics and figure skating have been designated early-specialization sports (Balyi et al., 2013; Vaeyens et al., 2009), in which elite levels of performance are achieved before puberty. Gymnastics and figure skating are subjectively judged, with performance expectations calling for smaller, lighter, more flexible bodies to execute the difficult skills required at the elite level. Thus, it is typical for gymnasts and skaters who aspire to attain elite status to begin extensive technical training very early, and there is evidence that expert athletes specialized earlier than nonexpert athletes in these sports (O'Connor, 2011). Former Olympian Dominique Moceanu began gymnastics at age 3, and by age 7 she was training six days a week for at least 25 hours per week.

Overall, research supports early diversification as facilitative to athletes' development in most sports. Kids can start their favorite sports early and also participate in other sports and activities. Early diversification doesn't mean that a young athlete can't spend a significant amount of time doing the sport he likes best. We would just recommend that early experiences in the late-specialization sports include a lot of deliberate play and spontaneous practice, as opposed to excessive levels of highly technical deliberate practice. - Early diversification develops a broad range of fundamental motor skills and different sport experiences that provide the athlete with more performance options and athleticism if they choose to specialize in one sport later. A youth baseball academy coach discusses highly specialized athletes who can perform the mechanics of their sport but lack well-rounded motor skills: "My God, this kid is a horrible athlete. He can't run. He can't move. He's spent all his time in the batting cage. So many of these kids have played no other sport. They're one-trick ponies" (Sokolove, 2008, p. 204).

David Leadbetter, internationally recognized golf instructor, coaches Charles Howell III, a PGA tour player who has not yet realized the great promise he showed as a junior golfer. Leadbetter says of Howell (whom he has coached from the age of 12): "Charles has had a solid career, but he hasn't hit the heights some thought he might. I have always felt part of his problem is that he played only golf growing up. That hurts him. In other ball games you develop a feel for throwing and distance. But Charles never did that. He doesn't have the instinctive touch or hand - eye coordination you need to hit the ball close [inside 120 yards, or 110 meters]. If only he'd played baseball as a kid. That would have helped his awareness for distance (Huggan, 2013, p. 37). - Early specialization has been linked to dropping out of sport. Ice hockey players who dropped out of their sport began off-ice training at a younger age and invested more hours per year in training at ages 12 and 13 as compared to active players (Wall & Cote, 2007). Both the dropout and active players enjoyed a diverse and playful introduction to sport, but the earlier specialized activities of the dropout players may have affected their motivation to continue in the sport.

A similar pattern was found in swimming (Fraser-Thomas, Cote, & Deakin, 2008a). Adolescent swimmers who dropped out were involved in fewer extracurricular activities and less unstructured swimming play during their early years, and also began more specialized training activities (training camps, dryland training) earlier than active swimmers. So although the starting ages of the dropout and active swimmers did not differ, the earlier specialized focus of the dropouts may have contributed to their discontinuation of swimming. Interestingly, dropout swimmers also reached "top in club" status earlier than active swimmers. The authors suggest that a comedown from child stardom to adolescent mediocrity, with resultant disappointment and decreased confidence, could occur for some kids who specialize and achieve early success.

Because dropping out is a motivational issue, it may be that early exclusive sport specialization does not allow youth athletes to experience the playful enjoyment found to be important to elite athlete development before age 12 (Bloom, 1985; Cote et al., 2003). A premature emphasis on technical training, deliberate practice, and competition may thwart the falling in love with a sport, which has repeatedly been shown to fuel the passion and commitment needed to continue to higher levels of sport. - Early specialization has been linked to burning out of sport. Another negative consequence that has been associated with early sport specialization is burnout. Discussed more fully in chapter 11, burnout occurs when a previously enjoyable activity becomes drudgery, so that athletes feel physically and emotionally exhausted. Adolescent athletes specializing in swimming, diving, and gymnastics were higher in emotional exhaustion (burnout) when compared to more diversified adolescent athletes who participated in a variety of activities (Strachan, Cote, & Deakin, 2009). A sole focus on tennis at a young age has also been linked to burnout (and dropout) in elite tennis players (Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996).

- Early diversification helps kids develop multidimensionality, or multiple pieces in their identity pie. The development of a multidimensional identity, or self-concept, is important for the mental health and well-being of children. Exclusive specialization at a young age can restrict children to a unidimensional self-concept, which has been linked to burnout and psychological dysfunction (Coakley, 1992). Adolescent athletes who were engaged in other activities (e.g., performing arts, school, church) along with their sport participation have been shown to possess healthier psychological profiles than adolescents who participated only in sport (Zarrett et al., 2008).

A useful activity to do with young athletes is to ask them to draw their personal identity pie, labeling various pieces of the pie to represent who they are. The pie on the left side of figure 10.4 provides a multidimensional example: A young tennis player identifies other personally significant activities or personal strengths that define who she is. The pie on the right side of figure 10.4 might be drawn by another young tennis player; she is narrowly unidimensional and would be vulnerable to major blows to her self-worth and self-concept when encountering obstacles in her pursuit of expertise in tennis. A multidimensional identity is a good insurance policy for kids because it provides them with broad coverage of their sense of self. Help young athletes develop lots of pieces in their pies.

Multidimensional versus unidimensional identity pie.

Structural Strategies to Avoid Overspecialization and Exclusive Specialization

To quell the rising tide of professionalization, overspecialization, and exclusive early specialization, policies and regulations should be instituted at the organizational level. "Developmentalizing" should always trump professionalizing when it comes to youth sport. Two examples are provided here, and we encourage you to consider additional ways to protect the interests of young athletes.

- Continue and expand the practice of implementing minimal age restrictions for athletes to compete in professional or international sport. The minimal age to compete internationally in gymnastics rose from 14 years before 1981, to 15 years in 1981, to 16 years in 1997 (one is eligible if one achieves the minimal age sometime in the Olympic or competition year). The age restriction is designed to protect child athletes from injury and exploitation, although it remains controversial, often with accusations of age falsification for international events. Professional tennis has a minimum age requirement of 14 years. The National Basketball Association requires draftees to be 19 years and one year removed from high school graduation, while prospects may be drafted right out of high school for Major League Baseball.

These restrictions are important because they have a trickle-down effect on youth sport. When Kevin Garnett signed as the fifth pick in the National Basketball Association draft in 1995 straight out of high school, the search for star players moved down from high school to elementary school (Dohrmann, 2010). It fueled the pressure on kids to play year-round and travel extensively at extremely young ages to compete in national tournaments. For example, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) has sponsored a 2nd-grade boys' national championship tournament since 2004. Sport organizations and youth sport leaders should continue to lobby for age restrictions to protect kids from pressure to specialize early and exclusively. - No athlete should be restricted from diversification through high school participation. This recommendation is designed to preserve young athletes' rights to diversify their sport participation through their high school years. Others have recommended 15 years as the cutoff age for protected diversification (Wiersma, 2000), and we agree that this is a logical age cutoff. However, we see no reason that adults should mandate specialization before college when 98% of high school athletes are not going on to play at the collegiate level. Coaches and parents should guide young athletes in making important decisions about multiple sport participation versus more specialized approaches. But this should be discussed on an individual-case basis and should ultimately be the athlete's decision. We urge athletic directors and state and national high school sport associations to develop regulations that prevent coaches from having the power to restrict athletes' activities.

Save

Learn more about Best Practice for Youth Sport.

Burnout in Youth Sport

I don’t know, Mom, I just feel burned out. As a parent, what would you do if you heard this? We all have a vague understanding of burnout, but should we advise our kids to drop out, take a break, make some changes, or suck it up?

"I don't know, Mom, I just feel burned out." As a parent, what would you do if you heard this? We all have a vague understanding of burnout, but should we advise our kids to drop out, take a break, make some changes, or suck it up? Because burnout is a popular term, we need to carefully consider what is true and not true about burnout in youth athletes.

What Is Burnout?

Burnout is a negative psychological and physical state in which young athletes feel tired, less able to perform well, and less interested in playing their sports. Three symptoms characterize burnout.

Physical and Emotional Exhaustion

Although it is common for athletes to get tired after training sessions or competitions, the exhaustion associated with burnout involves the depletion of emotional and physical resources beyond the typical tiredness that comes and goes throughout a sport season. Parents may notice kids feeling too tired to do things outside their sport, feeling emotionally drained and lethargic, and wanting to take a break from sport.

Reduced Sport Accomplishment

The second symptom can be a lack of performance success or inconsistent performance, or it can be more about the perception on the part of the athlete that she is not playing up to her potential. The athlete may feel that she's not getting anywhere - for example, not improving or moving forward.

Devaluation of Sport

Devaluation means a reduction in value: The athlete doesn't care as much about his sport. Athletes may say "I'm sick of doing this"; "I don't care about playing anymore"; or "It's just not fun anymore." Another common symptom is questioning things - for example, "Why am I doing this?"

How Prevalent Is Burnout in Youth Sport?