Sport First Aid

328 Pages

As a coach, you’ll likely be first on the scene when one of your athletes falls ill or suffers an injury. Are you prepared to take action in a medical emergency?

Sport First Aid provides high school and club sport coaches with detailed action steps for the care and prevention of more than 110 sport-related injuries and illnesses.

Organized for quick reference, Sport First Aid covers procedures for conducting emergency action steps; performing the physical assessment; administering first aid for bleeding, tissue damage, and unstable injuries; moving an injured athlete; and returning athletes to play.

The new edition explains the latest CPR techniques from the American Heart Association; guidelines for the prevention, recognition, and treatment of concussion from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and guidelines for the prevention of dehydration and heat illness from the National Athletic Trainers’ Association.

Beyond simply treating injuries and illnesses, Sport First Aid seeks to prevent them from occurring in the first place. Included are strategies for reducing athletes’ risk of injury or illness, such as establishing a school-based medical team, implementing preseason conditioning programs, creating safe playing environments, planning for weather emergencies, ensuring proper fit and use of protective equipment, enforcing sport skills and safety rules, and developing a medical emergency plan. Sample forms, checklists, and plans take the work out of developing these documents from scratch.

With Sport First Aid, you and your coaching staff will be prepared to make critical decisions and respond appropriately when faced with athletes’ injuries and illnesses.

Sport First Aid is the text for the Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition Online Course, offered through Human Kinetics Coach Education and recognized by numerous state high school associations and school districts as meeting coach education and certification requirements. For more information on Human Kinetics Coach Education courses and resources, call 800-747-5698 or visit CoachEducation.HumanKinetics.com.

Part I Introduction to Sport First Aid

Chapter 1 Your Role on the Athletic Health Care Team

Chapter 2 Sport First Aid Game Plan

Part II Basic Sport First Aid Skills

Chapter 3 Anatomy and Sport Injury Terminology

Chapter 4 Emergency Action Steps

Chapter 5 Physical Assessment and First Aid Techniques

Chapter 6 Moving Injured or Sick Athletes

Part III Sport First Aid for Specific Injuries

Chapter 7 Respiratory Emergencies and Illnesses

Chapter 8 Head, Spine, and Nerve Injuries

Chapter 9 Internal Organ Injuries

Chapter 10 Sudden Illnesses

Chapter 11 Weather-Related Problems

Chapter 12 Upper Body Musculoskeletal Injuries

Chapter 13 Lower Body Musculoskeletal Injuries

Chapter 14 Facial and Scalp Injuries

Chapter 15 Skin Problems

Melinda J. Flegel has 27 years of experience as a certified athletic trainer. For 13 years, she was head athletic trainer at the University of Illinois SportWell Center, where she oversaw sports medicine care and injury prevention education for the university’s recreational and club sport athletes.

As coordinator of outreach services at the Great Plains Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation Center in Peoria, Illinois, Flegel provided athletic training services to athletes at more than 15 high schools and regularly consulted with their coaches about sport first aid. As the center’s educational program coordinator and an American Red Cross CPR instructor, Flegel gained valuable firsthand experience in helping coaches become proficient first responders.

Flegel has taught a sports injury course at the University of Illinois. She holds master’s and bachelor’s degrees from the University of Illinois, is a member of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association and the National Strength and Conditioning Association, and has been a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist since 1987.

In addition to writing Sport First Aid, Flegel has written several book chapters, including Injury Prevention and First Aid for the Health on Demand textbook.

Learn how to assess and prevent heat-related illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range.

Prevention of Exertional Heat-Related Illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range. Here's how:

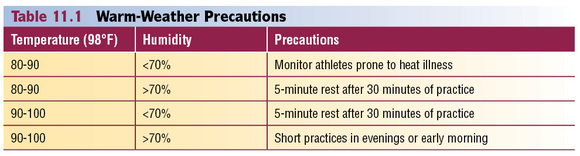

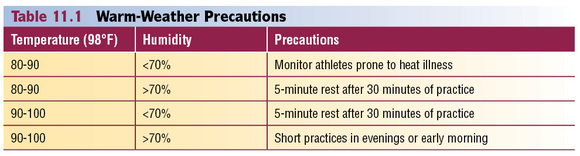

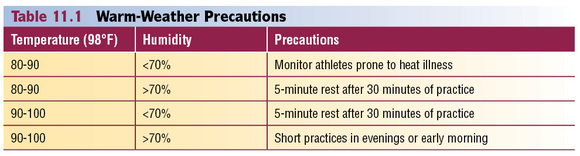

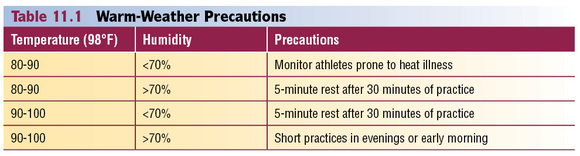

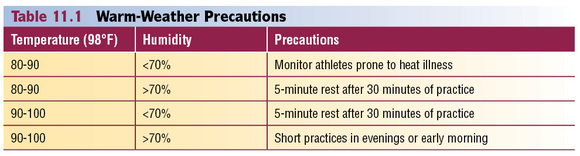

Monitor weather conditions and adjust practices accordingly. Table 11.1 shows the specific air temperature and humidity percentages that can be hazardous. Keep in mind, however that football exertional heat-related deaths have occurred at temperatures as low as 82 degrees with a relative humidity index at only 40 percent. If heat and humidity are equal to or higher than these conditions, make sure athletes are acclimated to the weather and are wearing light practice clothing. Schedule practices for early morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day.

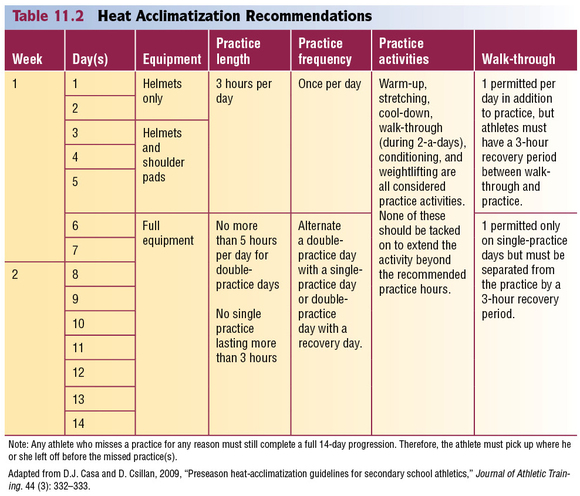

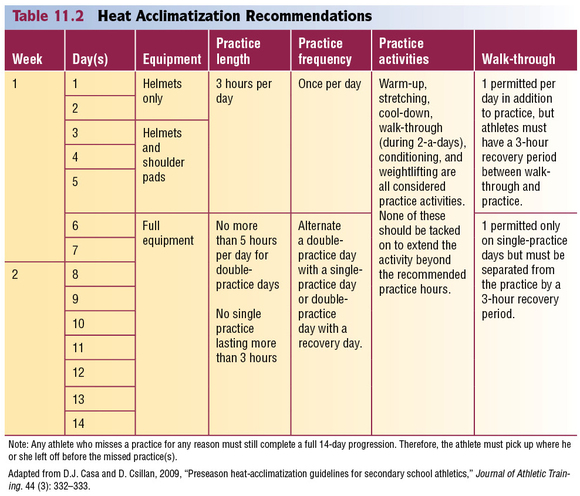

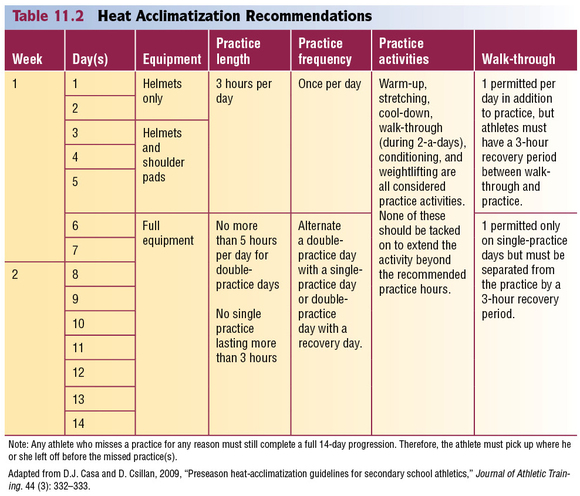

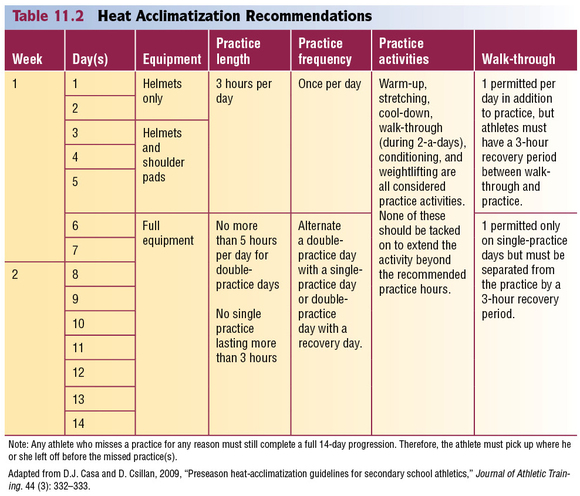

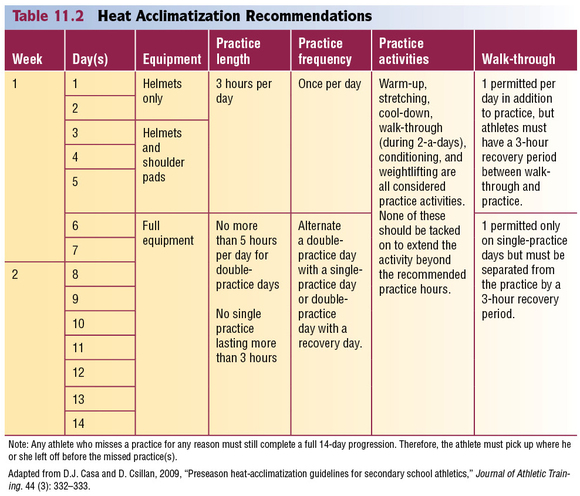

Acclimate athletes to exercising in high heat and humidity. If you are located in a warm-weather climate or have practices during the summer, athletes need time (approximately 7 to 10 days) to adjust to high heat and humidity. During this time, hold short practices at low to moderate activity levels and provide fluid and rest breaks every 15 to 20 minutes. The National Athletic Trainers' Association 2009 Consensus Statement offers more specific guidelines for acclimating high school athletes to hot environmental conditions. Table 11.2 summarizes the organization's recommendations.

Switch to light clothing and less equipment. Athletes stay cooler if they wear shorts, white T-shirts, and less equipment (especially helmets and pads). Equipment blocks the ability of sweat to evaporate. It's especially important for athletes to wear light clothing and minimal equipment while they are acclimating to the heat.

Identify and monitor athletes who are prone to heat illness. Athletes who have previously suffered a heat illness and those with the sickle cell trait are particularly prone to exertional heat illness and should be continuously monitored during activity. Dehydrated, overweight, heavily muscled, or deconditioned athletes are at risk, as well as athletes taking certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, some asthma medications, certain supplements, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications). Closely monitor these athletes and make sure they drink plenty of fluids. Rest dehydrated athletes until they have become rehydrated (see next bullet for more information on adequate hydration).

The signs and symptoms of dehydration include

- thirst,

- flushed skin,

- fatigue,

- muscle cramps,

- apathy,

- dry lips and mouth,

- dark colored urine (should be clear or light yellow), and

- feeling weak.

Strictly enforce adequate hydration.Athletes can lose a great deal of water through sweat. If this fluid is not replaced, the body will have less water to cool itself and will become dehydrated. Dehydration not only increases athletes' risk for heat illness, it also decreases their performance. In fact, athletic performance may worsen after only 2 percent of the body weight is lost through sweat. For example, dehydrated athletes may experience

- decreased muscle strength,

- increased fatigue,

- decreased mental function (e.g., concentration), and

- decreased endurance.

Don't rely on athletes to drink enough fluids on their own. Most won't actually feel thirsty until they've lost 3 percent or more of their body weight in sweat (water). By that time their performance will have started to decrease and their risk of exertional heat illness will have increased. Also, they may not drink enough fluid to replenish the water lost through sweat.

For proper hydration, the National Athletic Trainers' Association (Casa et al. 2000) recommends

- 17 to 20 fluid ounces of fluid at least 2 hours before workouts, practice, or competition;

- another 7 to 10 fluid ounces of water or sports drink 10 to 15 minutes before workouts, practice, or competition;

- as a general guideline, 7 to 10 fluid ounces of cool (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) water or sports drink every 10 to 20 minutes during workouts, practice, or competition; and

- after workouts, practices, and competitions, 24 fluid ounces of water or sports drink for every pound of fluid lost through sweat (Manore et al. 2000).

- To determine the amount of weight lost through sweat, weigh athletes in their underwear before and after practices and competitions that take place in high heat and humidity.

Replenish electrolytes lost through sweat. During activities lasting longer than 45 to 50 minutes, substantial amounts of electrolytes such as sodium (salt) and potassium are lost in sweat. They are used in muscle contraction, fluid balance, and other body functions, and therefore must be replaced. In addition, sodium plays a role in activating the body's thirst mechanism, so it can stimulate athletes to drink (keep hydrated). The best way for athletes to replace these nutrients is by drinking a sports beverage (containing sodium) and eating a normal diet. Athletes can also replace sodium by lightly salting their food, so salt tablets are not recommended. Just a small amount of potassium is lost in sweat. Oranges and bananas are good sources of potassium.

Prohibit the use of sweatboxes, vinyl suits, diuretics, or other artificial means of quick weight reduction.The NFHS Wrestling Rules Committee has already prohibited these methods.

Identifying and Treating Exertional Heat Illnesses

During physical activity, the body can produce 10 to 20 times the amount of heat that it produces at rest (metabolism). Approximately 75 percent of this heat must be eliminated. If the air temperature is less than the body temperature, radiation, conduction, and convection can help dissipate 65 to 75 percent of this heat. However, if the air temperature is near the body temperature, these modes of heat loss are less effective, and the body has to rely more on perspiration. High humidity reduces the amount of sweat evaporation, and thus leaves exercising athletes at risk of exertional heat illness.

The following sections will cover three types of exertional heat illness:

- Heat cramps

- Heat exhaustion

- Heatstroke

Each has different signs and symptoms, as well as different first aid interventions. Heatstroke is life threatening, whereas heat exhaustion and heat cramps typically are not. Therefore, it is important that you learn to evaluate the signs and symptoms and learn to apply the first aid techniques that are appropriate for each illness.

Save

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

What to do if an athlete has a head injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Athlete With a Head Injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Causes

- Direct blow to the head

- Sudden, forceful jarring or whipping of the head

Ask if Experiencing Symptoms

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Ringing in the ears

- Grogginess

- Nausea

- Blurred or double vision

Check for Signs

- Confusion

- Unsteadiness

- Inability to multitask (unable to do several athletic skills at once or do a skill correctly when distracted)

- Short-term memory loss

- Emotional changes such as a short temper or depression

- Unresponsiveness to touch or voice (call out the athlete's name and tap on the shoulder)

- Irregular breathing

- Bleeding or a wound at the point of the blow

- Blood or fluid leaking from the mouth, nose, or ears

- Arm or leg weakness or numbness

- Neck pain with a decrease in motion

- Bump or deformity at the point of the blow

- Convulsions

- Abnormalities in pupils (unequal in size or failure to constrict to light)

- Vomiting

First Aid

If an athlete exhibits any of the previously listed signs or symptoms, pull the athlete out of activity. Symptoms such as headache or ringing in the ears may be the early signs of a more serious injury. In these cases, do the following:

- Continue to monitor the athlete and alert emergency medical services if signs and symptoms worsen.

- Immediately contact the parent or guardian and have them take the athlete to a physician.

- Give the parent or guardian a checklist of signs and symptoms to monitor.

For injuries with more severe signs such as confusion, unsteadiness, vomiting, convulsions, increasing headaches, increasing irritability, unusual behavior, arm or leg weakness or numbness, neck pain with a decrease in motion, pupil abnormalities, or unconsciousness, do the following:

- Immediately call emergency medical services.

- Stabilize the head and neck until EMS takes over. Leave an athlete's helmet on when stabilizing the head and neck. You don't want to jar the head or neck unnecessarily. This is especially true if the athlete is also wearing shoulder pads.

- Monitor the athlete for breathing difficulty and perform CPR if necessary.

- Control any profuse bleeding but avoid applying excess pressure over a head wound.

- Monitor for shock and treat as needed.

- Immobilize any fractures or unstable injuries as long as it does not jostle the athlete, which may worsen his or her condition.

Playing Status

When can an athlete return to a sport after a brain injury? In most cases, this decision has already been decided for you. Check your state law or the regulations of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) to ensure that your athletes are receiving mandated care and supervision. The NFHS prohibits athletes from returning to activity until examined and released by a physician. Many states are enacting laws with similar or stricter guidelines. Check your state for specific laws regarding brain injuries in athletes.

Prevention

- Educate yourself, your athletes, and their parents or guardians about concussions. Visit the CDC website at www.cdc.gov.

- During preseason physicals, screen for any history of head, spine, or nerve injuries. Have these athletes cleared by a physician, preferably a neurologist, before allowing them to participate.

- Use preseason brain testing. Numerous software programs or testing contractors can assess each athlete's normal brain function, including memory, cognitive functioning, motor (muscle and balance) control, and other functions before the beginning of a sport season. This information is then used as a baseline from which an athlete's brain function can be compared when an injury is suspected or has occurred. Doctors and athletic trainers can monitor this information while the athlete recovers and determine when an athlete is ready to progressively return to activity. These tests can also be used to monitor the athlete for any signs of decreasing brain function as he or she progresses back into full participation. A decrease in function signals that the athlete is not ready to proceed further and may need to actually decrease activity. This type of testing can be an important tool for you, your athletes, and their physicians in helping to more objectively determine the severity of a brain injury, the level of recovery, and the athlete's readiness to return to activity.

- Incorporate neck strengthening exercises into your preseason and in-season conditioning programs. These can be done simply by providing resistance to the head with a hand against all of its normal movements.

For sports requiring helmets, ensure the following:

- Helmets are regularly checked for damage and replaced if necessary.

- Older helmets are regularly replaced.

- Helmets are properly fitted to each athlete.

- Athletes are instructed in effectively securing helmets in place. A well-fitted helmet isn't effective if chin straps are not snapped and snug.

- Athletes are repeatedly reminded not to use the top of the helmet as a point of contact when tackling or checking another player or lowering the head just before contacting another athlete. Enforce this rule as necessary by sidelining offending athletes and reinforcing proper technique.

- Prohibit diving into water less than 6 feet deep.

- Train and use spotters at all times during gymnastics and cheerleading.

- Monitor athletes for signs or symptoms of head injury.

- Educate athletes about the signs and symptoms of head injuries. Encourage athletes to report signs of suspected brain injury in teammates. Consider providing some sort of recognition to these athletes in order to encourage reporting.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Defining a coach's role on the Athletics Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Coach's Role on the Athletic Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Your roles are defined by

- certain rules of the legal system and rules of your school administration,

- expectations of parents, and

- interactions with other athletic health care team members.

Legal Definitions of Your Role

Basically, the legal system supports the theory that a coach's primary role is to minimize the risk of injury to the athletes under the coach's supervision. This encompasses a variety of duties.

1. Properly plan the activity.

- Teach the skills of the sport in the correct progression.

- Consider each athlete's developmental level and current physical condition. Evaluate your athletes' physical capacity and skill level with preseason fitness tests, and develop practice plans accordingly.

- Keep written records of fitness test results and practice plans. Don't deviate from your plans without good cause.

2. Provide proper instruction.

- Make sure that athletes are in proper condition to participate.

- Teach athletes the rules and the correct skills and strategies of the sport. For example, in football teach athletes that tackling with the head (spearing) is illegal and also a potentially dangerous technique.

- Teach athletes the sport skills and conditioning exercises in a progression so that the athletes are adequately prepared to handle more difficult skills or exercises.

- Keep up-to-date on better and safer ways of performing the techniques used in the sport.

- Provide competent and responsible assistants. If you have coaching assistants, make sure that they are knowledgeable in the skills and strategies of the sport and act in a mature and responsible manner.

3. Warn of inherent risks.

- Provide parents and athletes with both oral and written statements of the inherent health risks of their particular sport.

- Also warn athletes about potentially harmful conditions, such as playing conditions, dangerous or faulty equipment, and the like.

4. Provide a safe physical environment.

- Monitor current environmental conditions (i.e., windchill, temperature, humidity, and severe weather warnings).

- Periodically inspect the playing areas, the locker room, the weight room, and the dugout for hazards.

- Remove all hazards.

- Prevent improper or unsupervised use of facilities.

5. Provide adequate and proper equipment.

- Make sure athletes are using equipment that provides the maximum amount of protection against injury.

- Inspect equipment regularly.

- Teach athletes how to fit, use, and inspect their equipment.

6. Match your athletes appropriately.

- Match the athletes according to size, physical maturity, skill level, and experience.

- Do not pit physically immature or novice athletes against those who are in top condition and are highly skilled.

7. Evaluate athletes for injury or incapacity.

- Require all athletes to submit to preseason physicals and screenings to detect potential health problems.

- Withhold an athlete from practice and competition if the athlete is unable to compete without pain or loss of function (e.g., inability to walk, run, jump, throw, and so on without restriction).

8. Supervise the activity closely.

- Do not allow athletes to practice difficult or potentially dangerous skills without proper supervision.

- Forbid horseplay, such as “wrestling around.”

- Do not allow athletes to use sports facilities without supervision.

9. Provide appropriate emergency assistance.

- Learn sport first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). (Take a course through the American Red Cross, American Heart Association, or the National Safety Council.)

- Take action when needed. The law assumes that you, as a coach, are responsible for providing first aid care for any injury or illness suffered by an athlete under your supervision. So, if no medical personnel are present when an injury occurs, you are responsible for providing emergency care.

- Use only the skills that you are qualified to administer and provide the specific standard of care that you are trained to provide through sport first aid, CPR, and other sports medicine courses.

- If athlete is a minor, obtain a signed written consent form from their parents before the season. For injured adult athletes, specifically ask if they want help. If they are unresponsive, consent is usually implied. If they refuse help, you are not required to provide it. In fact, if you still attempt to give care, they can sue you for assault.

Some states expect coaches to meet additional standards of care. Check with your athletic director to find out if your state has specific guidelines for the quality of care to be provided by coaches.

You should become familiar with each of these 9 legal duties. The first 8 duties deal mainly with preventive measures, which are explained more thoroughly in chapter 2. This book is primarily designed to help you handle duty number 9.

Parental Expectations

Parents will look to you for direction when their child is injured. They may ask questions such as these:

What do you think is wrong with my child's knee?

Will it get worse if my child continues playing?

Should my child see a doctor?

Does my child need to wear protective knee braces for football?

Will taping help prevent my child from reinjuring the ankle?

When can my child start competing again?

While you can't have all the answers, it helps to know those who can. That's where the other athletic health care team members can help. Let's look at the other members of the team, their roles, and your roles in interacting with them.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Learn how to assess and prevent heat-related illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range.

Prevention of Exertional Heat-Related Illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range. Here's how:

Monitor weather conditions and adjust practices accordingly. Table 11.1 shows the specific air temperature and humidity percentages that can be hazardous. Keep in mind, however that football exertional heat-related deaths have occurred at temperatures as low as 82 degrees with a relative humidity index at only 40 percent. If heat and humidity are equal to or higher than these conditions, make sure athletes are acclimated to the weather and are wearing light practice clothing. Schedule practices for early morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day.

Acclimate athletes to exercising in high heat and humidity. If you are located in a warm-weather climate or have practices during the summer, athletes need time (approximately 7 to 10 days) to adjust to high heat and humidity. During this time, hold short practices at low to moderate activity levels and provide fluid and rest breaks every 15 to 20 minutes. The National Athletic Trainers' Association 2009 Consensus Statement offers more specific guidelines for acclimating high school athletes to hot environmental conditions. Table 11.2 summarizes the organization's recommendations.

Switch to light clothing and less equipment. Athletes stay cooler if they wear shorts, white T-shirts, and less equipment (especially helmets and pads). Equipment blocks the ability of sweat to evaporate. It's especially important for athletes to wear light clothing and minimal equipment while they are acclimating to the heat.

Identify and monitor athletes who are prone to heat illness. Athletes who have previously suffered a heat illness and those with the sickle cell trait are particularly prone to exertional heat illness and should be continuously monitored during activity. Dehydrated, overweight, heavily muscled, or deconditioned athletes are at risk, as well as athletes taking certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, some asthma medications, certain supplements, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications). Closely monitor these athletes and make sure they drink plenty of fluids. Rest dehydrated athletes until they have become rehydrated (see next bullet for more information on adequate hydration).

The signs and symptoms of dehydration include

- thirst,

- flushed skin,

- fatigue,

- muscle cramps,

- apathy,

- dry lips and mouth,

- dark colored urine (should be clear or light yellow), and

- feeling weak.

Strictly enforce adequate hydration.Athletes can lose a great deal of water through sweat. If this fluid is not replaced, the body will have less water to cool itself and will become dehydrated. Dehydration not only increases athletes' risk for heat illness, it also decreases their performance. In fact, athletic performance may worsen after only 2 percent of the body weight is lost through sweat. For example, dehydrated athletes may experience

- decreased muscle strength,

- increased fatigue,

- decreased mental function (e.g., concentration), and

- decreased endurance.

Don't rely on athletes to drink enough fluids on their own. Most won't actually feel thirsty until they've lost 3 percent or more of their body weight in sweat (water). By that time their performance will have started to decrease and their risk of exertional heat illness will have increased. Also, they may not drink enough fluid to replenish the water lost through sweat.

For proper hydration, the National Athletic Trainers' Association (Casa et al. 2000) recommends

- 17 to 20 fluid ounces of fluid at least 2 hours before workouts, practice, or competition;

- another 7 to 10 fluid ounces of water or sports drink 10 to 15 minutes before workouts, practice, or competition;

- as a general guideline, 7 to 10 fluid ounces of cool (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) water or sports drink every 10 to 20 minutes during workouts, practice, or competition; and

- after workouts, practices, and competitions, 24 fluid ounces of water or sports drink for every pound of fluid lost through sweat (Manore et al. 2000).

- To determine the amount of weight lost through sweat, weigh athletes in their underwear before and after practices and competitions that take place in high heat and humidity.

Replenish electrolytes lost through sweat. During activities lasting longer than 45 to 50 minutes, substantial amounts of electrolytes such as sodium (salt) and potassium are lost in sweat. They are used in muscle contraction, fluid balance, and other body functions, and therefore must be replaced. In addition, sodium plays a role in activating the body's thirst mechanism, so it can stimulate athletes to drink (keep hydrated). The best way for athletes to replace these nutrients is by drinking a sports beverage (containing sodium) and eating a normal diet. Athletes can also replace sodium by lightly salting their food, so salt tablets are not recommended. Just a small amount of potassium is lost in sweat. Oranges and bananas are good sources of potassium.

Prohibit the use of sweatboxes, vinyl suits, diuretics, or other artificial means of quick weight reduction.The NFHS Wrestling Rules Committee has already prohibited these methods.

Identifying and Treating Exertional Heat Illnesses

During physical activity, the body can produce 10 to 20 times the amount of heat that it produces at rest (metabolism). Approximately 75 percent of this heat must be eliminated. If the air temperature is less than the body temperature, radiation, conduction, and convection can help dissipate 65 to 75 percent of this heat. However, if the air temperature is near the body temperature, these modes of heat loss are less effective, and the body has to rely more on perspiration. High humidity reduces the amount of sweat evaporation, and thus leaves exercising athletes at risk of exertional heat illness.

The following sections will cover three types of exertional heat illness:

- Heat cramps

- Heat exhaustion

- Heatstroke

Each has different signs and symptoms, as well as different first aid interventions. Heatstroke is life threatening, whereas heat exhaustion and heat cramps typically are not. Therefore, it is important that you learn to evaluate the signs and symptoms and learn to apply the first aid techniques that are appropriate for each illness.

Save

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

What to do if an athlete has a head injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Athlete With a Head Injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Causes

- Direct blow to the head

- Sudden, forceful jarring or whipping of the head

Ask if Experiencing Symptoms

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Ringing in the ears

- Grogginess

- Nausea

- Blurred or double vision

Check for Signs

- Confusion

- Unsteadiness

- Inability to multitask (unable to do several athletic skills at once or do a skill correctly when distracted)

- Short-term memory loss

- Emotional changes such as a short temper or depression

- Unresponsiveness to touch or voice (call out the athlete's name and tap on the shoulder)

- Irregular breathing

- Bleeding or a wound at the point of the blow

- Blood or fluid leaking from the mouth, nose, or ears

- Arm or leg weakness or numbness

- Neck pain with a decrease in motion

- Bump or deformity at the point of the blow

- Convulsions

- Abnormalities in pupils (unequal in size or failure to constrict to light)

- Vomiting

First Aid

If an athlete exhibits any of the previously listed signs or symptoms, pull the athlete out of activity. Symptoms such as headache or ringing in the ears may be the early signs of a more serious injury. In these cases, do the following:

- Continue to monitor the athlete and alert emergency medical services if signs and symptoms worsen.

- Immediately contact the parent or guardian and have them take the athlete to a physician.

- Give the parent or guardian a checklist of signs and symptoms to monitor.

For injuries with more severe signs such as confusion, unsteadiness, vomiting, convulsions, increasing headaches, increasing irritability, unusual behavior, arm or leg weakness or numbness, neck pain with a decrease in motion, pupil abnormalities, or unconsciousness, do the following:

- Immediately call emergency medical services.

- Stabilize the head and neck until EMS takes over. Leave an athlete's helmet on when stabilizing the head and neck. You don't want to jar the head or neck unnecessarily. This is especially true if the athlete is also wearing shoulder pads.

- Monitor the athlete for breathing difficulty and perform CPR if necessary.

- Control any profuse bleeding but avoid applying excess pressure over a head wound.

- Monitor for shock and treat as needed.

- Immobilize any fractures or unstable injuries as long as it does not jostle the athlete, which may worsen his or her condition.

Playing Status

When can an athlete return to a sport after a brain injury? In most cases, this decision has already been decided for you. Check your state law or the regulations of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) to ensure that your athletes are receiving mandated care and supervision. The NFHS prohibits athletes from returning to activity until examined and released by a physician. Many states are enacting laws with similar or stricter guidelines. Check your state for specific laws regarding brain injuries in athletes.

Prevention

- Educate yourself, your athletes, and their parents or guardians about concussions. Visit the CDC website at www.cdc.gov.

- During preseason physicals, screen for any history of head, spine, or nerve injuries. Have these athletes cleared by a physician, preferably a neurologist, before allowing them to participate.

- Use preseason brain testing. Numerous software programs or testing contractors can assess each athlete's normal brain function, including memory, cognitive functioning, motor (muscle and balance) control, and other functions before the beginning of a sport season. This information is then used as a baseline from which an athlete's brain function can be compared when an injury is suspected or has occurred. Doctors and athletic trainers can monitor this information while the athlete recovers and determine when an athlete is ready to progressively return to activity. These tests can also be used to monitor the athlete for any signs of decreasing brain function as he or she progresses back into full participation. A decrease in function signals that the athlete is not ready to proceed further and may need to actually decrease activity. This type of testing can be an important tool for you, your athletes, and their physicians in helping to more objectively determine the severity of a brain injury, the level of recovery, and the athlete's readiness to return to activity.

- Incorporate neck strengthening exercises into your preseason and in-season conditioning programs. These can be done simply by providing resistance to the head with a hand against all of its normal movements.

For sports requiring helmets, ensure the following:

- Helmets are regularly checked for damage and replaced if necessary.

- Older helmets are regularly replaced.

- Helmets are properly fitted to each athlete.

- Athletes are instructed in effectively securing helmets in place. A well-fitted helmet isn't effective if chin straps are not snapped and snug.

- Athletes are repeatedly reminded not to use the top of the helmet as a point of contact when tackling or checking another player or lowering the head just before contacting another athlete. Enforce this rule as necessary by sidelining offending athletes and reinforcing proper technique.

- Prohibit diving into water less than 6 feet deep.

- Train and use spotters at all times during gymnastics and cheerleading.

- Monitor athletes for signs or symptoms of head injury.

- Educate athletes about the signs and symptoms of head injuries. Encourage athletes to report signs of suspected brain injury in teammates. Consider providing some sort of recognition to these athletes in order to encourage reporting.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Defining a coach's role on the Athletics Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Coach's Role on the Athletic Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Your roles are defined by

- certain rules of the legal system and rules of your school administration,

- expectations of parents, and

- interactions with other athletic health care team members.

Legal Definitions of Your Role

Basically, the legal system supports the theory that a coach's primary role is to minimize the risk of injury to the athletes under the coach's supervision. This encompasses a variety of duties.

1. Properly plan the activity.

- Teach the skills of the sport in the correct progression.

- Consider each athlete's developmental level and current physical condition. Evaluate your athletes' physical capacity and skill level with preseason fitness tests, and develop practice plans accordingly.

- Keep written records of fitness test results and practice plans. Don't deviate from your plans without good cause.

2. Provide proper instruction.

- Make sure that athletes are in proper condition to participate.

- Teach athletes the rules and the correct skills and strategies of the sport. For example, in football teach athletes that tackling with the head (spearing) is illegal and also a potentially dangerous technique.

- Teach athletes the sport skills and conditioning exercises in a progression so that the athletes are adequately prepared to handle more difficult skills or exercises.

- Keep up-to-date on better and safer ways of performing the techniques used in the sport.

- Provide competent and responsible assistants. If you have coaching assistants, make sure that they are knowledgeable in the skills and strategies of the sport and act in a mature and responsible manner.

3. Warn of inherent risks.

- Provide parents and athletes with both oral and written statements of the inherent health risks of their particular sport.

- Also warn athletes about potentially harmful conditions, such as playing conditions, dangerous or faulty equipment, and the like.

4. Provide a safe physical environment.

- Monitor current environmental conditions (i.e., windchill, temperature, humidity, and severe weather warnings).

- Periodically inspect the playing areas, the locker room, the weight room, and the dugout for hazards.

- Remove all hazards.

- Prevent improper or unsupervised use of facilities.

5. Provide adequate and proper equipment.

- Make sure athletes are using equipment that provides the maximum amount of protection against injury.

- Inspect equipment regularly.

- Teach athletes how to fit, use, and inspect their equipment.

6. Match your athletes appropriately.

- Match the athletes according to size, physical maturity, skill level, and experience.

- Do not pit physically immature or novice athletes against those who are in top condition and are highly skilled.

7. Evaluate athletes for injury or incapacity.

- Require all athletes to submit to preseason physicals and screenings to detect potential health problems.

- Withhold an athlete from practice and competition if the athlete is unable to compete without pain or loss of function (e.g., inability to walk, run, jump, throw, and so on without restriction).

8. Supervise the activity closely.

- Do not allow athletes to practice difficult or potentially dangerous skills without proper supervision.

- Forbid horseplay, such as “wrestling around.”

- Do not allow athletes to use sports facilities without supervision.

9. Provide appropriate emergency assistance.

- Learn sport first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). (Take a course through the American Red Cross, American Heart Association, or the National Safety Council.)

- Take action when needed. The law assumes that you, as a coach, are responsible for providing first aid care for any injury or illness suffered by an athlete under your supervision. So, if no medical personnel are present when an injury occurs, you are responsible for providing emergency care.

- Use only the skills that you are qualified to administer and provide the specific standard of care that you are trained to provide through sport first aid, CPR, and other sports medicine courses.

- If athlete is a minor, obtain a signed written consent form from their parents before the season. For injured adult athletes, specifically ask if they want help. If they are unresponsive, consent is usually implied. If they refuse help, you are not required to provide it. In fact, if you still attempt to give care, they can sue you for assault.

Some states expect coaches to meet additional standards of care. Check with your athletic director to find out if your state has specific guidelines for the quality of care to be provided by coaches.

You should become familiar with each of these 9 legal duties. The first 8 duties deal mainly with preventive measures, which are explained more thoroughly in chapter 2. This book is primarily designed to help you handle duty number 9.

Parental Expectations

Parents will look to you for direction when their child is injured. They may ask questions such as these:

What do you think is wrong with my child's knee?

Will it get worse if my child continues playing?

Should my child see a doctor?

Does my child need to wear protective knee braces for football?

Will taping help prevent my child from reinjuring the ankle?

When can my child start competing again?

While you can't have all the answers, it helps to know those who can. That's where the other athletic health care team members can help. Let's look at the other members of the team, their roles, and your roles in interacting with them.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Learn how to assess and prevent heat-related illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range.

Prevention of Exertional Heat-Related Illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range. Here's how:

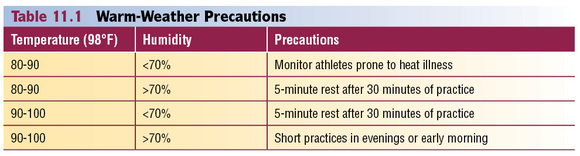

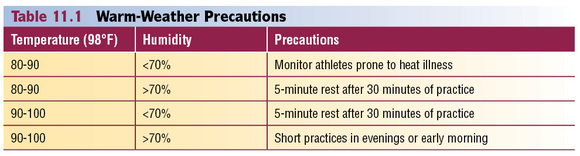

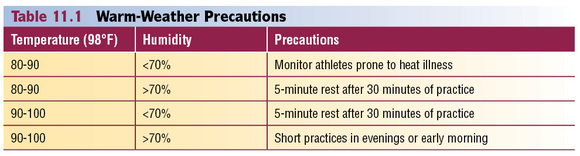

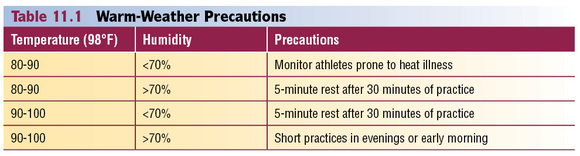

Monitor weather conditions and adjust practices accordingly. Table 11.1 shows the specific air temperature and humidity percentages that can be hazardous. Keep in mind, however that football exertional heat-related deaths have occurred at temperatures as low as 82 degrees with a relative humidity index at only 40 percent. If heat and humidity are equal to or higher than these conditions, make sure athletes are acclimated to the weather and are wearing light practice clothing. Schedule practices for early morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day.

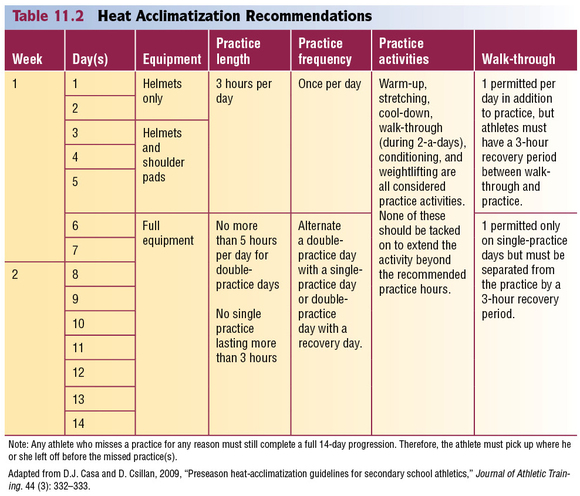

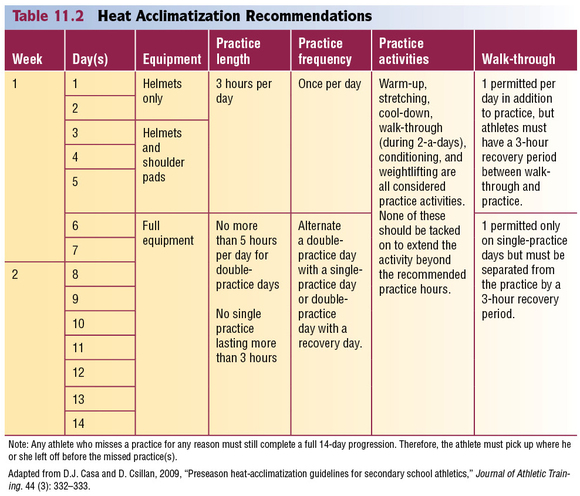

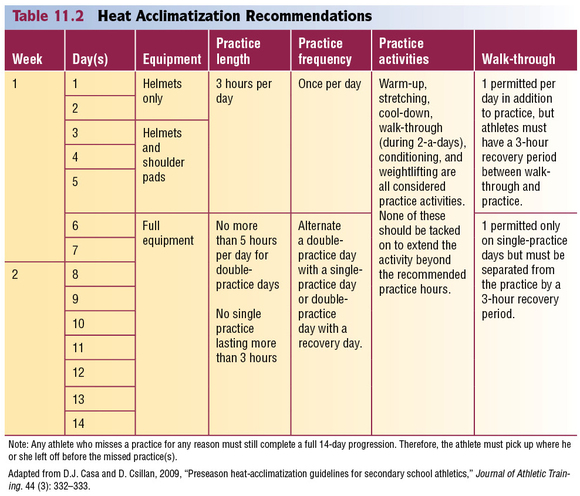

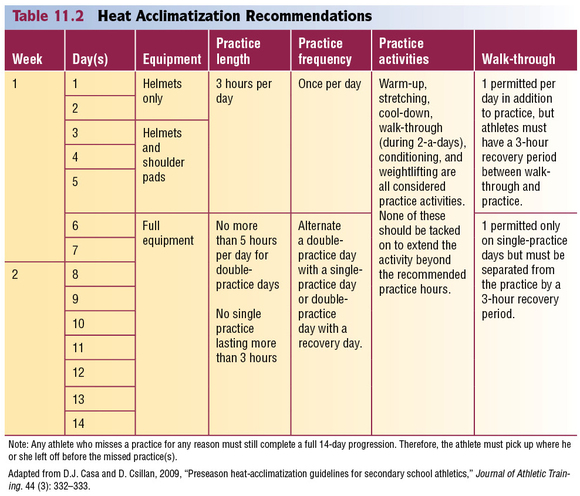

Acclimate athletes to exercising in high heat and humidity. If you are located in a warm-weather climate or have practices during the summer, athletes need time (approximately 7 to 10 days) to adjust to high heat and humidity. During this time, hold short practices at low to moderate activity levels and provide fluid and rest breaks every 15 to 20 minutes. The National Athletic Trainers' Association 2009 Consensus Statement offers more specific guidelines for acclimating high school athletes to hot environmental conditions. Table 11.2 summarizes the organization's recommendations.

Switch to light clothing and less equipment. Athletes stay cooler if they wear shorts, white T-shirts, and less equipment (especially helmets and pads). Equipment blocks the ability of sweat to evaporate. It's especially important for athletes to wear light clothing and minimal equipment while they are acclimating to the heat.

Identify and monitor athletes who are prone to heat illness. Athletes who have previously suffered a heat illness and those with the sickle cell trait are particularly prone to exertional heat illness and should be continuously monitored during activity. Dehydrated, overweight, heavily muscled, or deconditioned athletes are at risk, as well as athletes taking certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, some asthma medications, certain supplements, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications). Closely monitor these athletes and make sure they drink plenty of fluids. Rest dehydrated athletes until they have become rehydrated (see next bullet for more information on adequate hydration).

The signs and symptoms of dehydration include

- thirst,

- flushed skin,

- fatigue,

- muscle cramps,

- apathy,

- dry lips and mouth,

- dark colored urine (should be clear or light yellow), and

- feeling weak.

Strictly enforce adequate hydration.Athletes can lose a great deal of water through sweat. If this fluid is not replaced, the body will have less water to cool itself and will become dehydrated. Dehydration not only increases athletes' risk for heat illness, it also decreases their performance. In fact, athletic performance may worsen after only 2 percent of the body weight is lost through sweat. For example, dehydrated athletes may experience

- decreased muscle strength,

- increased fatigue,

- decreased mental function (e.g., concentration), and

- decreased endurance.

Don't rely on athletes to drink enough fluids on their own. Most won't actually feel thirsty until they've lost 3 percent or more of their body weight in sweat (water). By that time their performance will have started to decrease and their risk of exertional heat illness will have increased. Also, they may not drink enough fluid to replenish the water lost through sweat.

For proper hydration, the National Athletic Trainers' Association (Casa et al. 2000) recommends

- 17 to 20 fluid ounces of fluid at least 2 hours before workouts, practice, or competition;

- another 7 to 10 fluid ounces of water or sports drink 10 to 15 minutes before workouts, practice, or competition;

- as a general guideline, 7 to 10 fluid ounces of cool (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) water or sports drink every 10 to 20 minutes during workouts, practice, or competition; and

- after workouts, practices, and competitions, 24 fluid ounces of water or sports drink for every pound of fluid lost through sweat (Manore et al. 2000).

- To determine the amount of weight lost through sweat, weigh athletes in their underwear before and after practices and competitions that take place in high heat and humidity.

Replenish electrolytes lost through sweat. During activities lasting longer than 45 to 50 minutes, substantial amounts of electrolytes such as sodium (salt) and potassium are lost in sweat. They are used in muscle contraction, fluid balance, and other body functions, and therefore must be replaced. In addition, sodium plays a role in activating the body's thirst mechanism, so it can stimulate athletes to drink (keep hydrated). The best way for athletes to replace these nutrients is by drinking a sports beverage (containing sodium) and eating a normal diet. Athletes can also replace sodium by lightly salting their food, so salt tablets are not recommended. Just a small amount of potassium is lost in sweat. Oranges and bananas are good sources of potassium.

Prohibit the use of sweatboxes, vinyl suits, diuretics, or other artificial means of quick weight reduction.The NFHS Wrestling Rules Committee has already prohibited these methods.

Identifying and Treating Exertional Heat Illnesses

During physical activity, the body can produce 10 to 20 times the amount of heat that it produces at rest (metabolism). Approximately 75 percent of this heat must be eliminated. If the air temperature is less than the body temperature, radiation, conduction, and convection can help dissipate 65 to 75 percent of this heat. However, if the air temperature is near the body temperature, these modes of heat loss are less effective, and the body has to rely more on perspiration. High humidity reduces the amount of sweat evaporation, and thus leaves exercising athletes at risk of exertional heat illness.

The following sections will cover three types of exertional heat illness:

- Heat cramps

- Heat exhaustion

- Heatstroke

Each has different signs and symptoms, as well as different first aid interventions. Heatstroke is life threatening, whereas heat exhaustion and heat cramps typically are not. Therefore, it is important that you learn to evaluate the signs and symptoms and learn to apply the first aid techniques that are appropriate for each illness.

Save

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

What to do if an athlete has a head injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Athlete With a Head Injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Causes

- Direct blow to the head

- Sudden, forceful jarring or whipping of the head

Ask if Experiencing Symptoms

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Ringing in the ears

- Grogginess

- Nausea

- Blurred or double vision

Check for Signs

- Confusion

- Unsteadiness

- Inability to multitask (unable to do several athletic skills at once or do a skill correctly when distracted)

- Short-term memory loss

- Emotional changes such as a short temper or depression

- Unresponsiveness to touch or voice (call out the athlete's name and tap on the shoulder)

- Irregular breathing

- Bleeding or a wound at the point of the blow

- Blood or fluid leaking from the mouth, nose, or ears

- Arm or leg weakness or numbness

- Neck pain with a decrease in motion

- Bump or deformity at the point of the blow

- Convulsions

- Abnormalities in pupils (unequal in size or failure to constrict to light)

- Vomiting

First Aid

If an athlete exhibits any of the previously listed signs or symptoms, pull the athlete out of activity. Symptoms such as headache or ringing in the ears may be the early signs of a more serious injury. In these cases, do the following:

- Continue to monitor the athlete and alert emergency medical services if signs and symptoms worsen.

- Immediately contact the parent or guardian and have them take the athlete to a physician.

- Give the parent or guardian a checklist of signs and symptoms to monitor.

For injuries with more severe signs such as confusion, unsteadiness, vomiting, convulsions, increasing headaches, increasing irritability, unusual behavior, arm or leg weakness or numbness, neck pain with a decrease in motion, pupil abnormalities, or unconsciousness, do the following:

- Immediately call emergency medical services.

- Stabilize the head and neck until EMS takes over. Leave an athlete's helmet on when stabilizing the head and neck. You don't want to jar the head or neck unnecessarily. This is especially true if the athlete is also wearing shoulder pads.

- Monitor the athlete for breathing difficulty and perform CPR if necessary.

- Control any profuse bleeding but avoid applying excess pressure over a head wound.

- Monitor for shock and treat as needed.

- Immobilize any fractures or unstable injuries as long as it does not jostle the athlete, which may worsen his or her condition.

Playing Status

When can an athlete return to a sport after a brain injury? In most cases, this decision has already been decided for you. Check your state law or the regulations of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) to ensure that your athletes are receiving mandated care and supervision. The NFHS prohibits athletes from returning to activity until examined and released by a physician. Many states are enacting laws with similar or stricter guidelines. Check your state for specific laws regarding brain injuries in athletes.

Prevention

- Educate yourself, your athletes, and their parents or guardians about concussions. Visit the CDC website at www.cdc.gov.

- During preseason physicals, screen for any history of head, spine, or nerve injuries. Have these athletes cleared by a physician, preferably a neurologist, before allowing them to participate.

- Use preseason brain testing. Numerous software programs or testing contractors can assess each athlete's normal brain function, including memory, cognitive functioning, motor (muscle and balance) control, and other functions before the beginning of a sport season. This information is then used as a baseline from which an athlete's brain function can be compared when an injury is suspected or has occurred. Doctors and athletic trainers can monitor this information while the athlete recovers and determine when an athlete is ready to progressively return to activity. These tests can also be used to monitor the athlete for any signs of decreasing brain function as he or she progresses back into full participation. A decrease in function signals that the athlete is not ready to proceed further and may need to actually decrease activity. This type of testing can be an important tool for you, your athletes, and their physicians in helping to more objectively determine the severity of a brain injury, the level of recovery, and the athlete's readiness to return to activity.

- Incorporate neck strengthening exercises into your preseason and in-season conditioning programs. These can be done simply by providing resistance to the head with a hand against all of its normal movements.

For sports requiring helmets, ensure the following:

- Helmets are regularly checked for damage and replaced if necessary.

- Older helmets are regularly replaced.

- Helmets are properly fitted to each athlete.

- Athletes are instructed in effectively securing helmets in place. A well-fitted helmet isn't effective if chin straps are not snapped and snug.

- Athletes are repeatedly reminded not to use the top of the helmet as a point of contact when tackling or checking another player or lowering the head just before contacting another athlete. Enforce this rule as necessary by sidelining offending athletes and reinforcing proper technique.

- Prohibit diving into water less than 6 feet deep.

- Train and use spotters at all times during gymnastics and cheerleading.

- Monitor athletes for signs or symptoms of head injury.

- Educate athletes about the signs and symptoms of head injuries. Encourage athletes to report signs of suspected brain injury in teammates. Consider providing some sort of recognition to these athletes in order to encourage reporting.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Defining a coach's role on the Athletics Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Coach's Role on the Athletic Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Your roles are defined by

- certain rules of the legal system and rules of your school administration,

- expectations of parents, and

- interactions with other athletic health care team members.

Legal Definitions of Your Role

Basically, the legal system supports the theory that a coach's primary role is to minimize the risk of injury to the athletes under the coach's supervision. This encompasses a variety of duties.

1. Properly plan the activity.

- Teach the skills of the sport in the correct progression.

- Consider each athlete's developmental level and current physical condition. Evaluate your athletes' physical capacity and skill level with preseason fitness tests, and develop practice plans accordingly.

- Keep written records of fitness test results and practice plans. Don't deviate from your plans without good cause.

2. Provide proper instruction.

- Make sure that athletes are in proper condition to participate.

- Teach athletes the rules and the correct skills and strategies of the sport. For example, in football teach athletes that tackling with the head (spearing) is illegal and also a potentially dangerous technique.

- Teach athletes the sport skills and conditioning exercises in a progression so that the athletes are adequately prepared to handle more difficult skills or exercises.

- Keep up-to-date on better and safer ways of performing the techniques used in the sport.

- Provide competent and responsible assistants. If you have coaching assistants, make sure that they are knowledgeable in the skills and strategies of the sport and act in a mature and responsible manner.

3. Warn of inherent risks.

- Provide parents and athletes with both oral and written statements of the inherent health risks of their particular sport.

- Also warn athletes about potentially harmful conditions, such as playing conditions, dangerous or faulty equipment, and the like.

4. Provide a safe physical environment.

- Monitor current environmental conditions (i.e., windchill, temperature, humidity, and severe weather warnings).

- Periodically inspect the playing areas, the locker room, the weight room, and the dugout for hazards.

- Remove all hazards.

- Prevent improper or unsupervised use of facilities.

5. Provide adequate and proper equipment.

- Make sure athletes are using equipment that provides the maximum amount of protection against injury.

- Inspect equipment regularly.

- Teach athletes how to fit, use, and inspect their equipment.

6. Match your athletes appropriately.

- Match the athletes according to size, physical maturity, skill level, and experience.

- Do not pit physically immature or novice athletes against those who are in top condition and are highly skilled.

7. Evaluate athletes for injury or incapacity.

- Require all athletes to submit to preseason physicals and screenings to detect potential health problems.

- Withhold an athlete from practice and competition if the athlete is unable to compete without pain or loss of function (e.g., inability to walk, run, jump, throw, and so on without restriction).

8. Supervise the activity closely.

- Do not allow athletes to practice difficult or potentially dangerous skills without proper supervision.

- Forbid horseplay, such as “wrestling around.”

- Do not allow athletes to use sports facilities without supervision.

9. Provide appropriate emergency assistance.

- Learn sport first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). (Take a course through the American Red Cross, American Heart Association, or the National Safety Council.)

- Take action when needed. The law assumes that you, as a coach, are responsible for providing first aid care for any injury or illness suffered by an athlete under your supervision. So, if no medical personnel are present when an injury occurs, you are responsible for providing emergency care.

- Use only the skills that you are qualified to administer and provide the specific standard of care that you are trained to provide through sport first aid, CPR, and other sports medicine courses.

- If athlete is a minor, obtain a signed written consent form from their parents before the season. For injured adult athletes, specifically ask if they want help. If they are unresponsive, consent is usually implied. If they refuse help, you are not required to provide it. In fact, if you still attempt to give care, they can sue you for assault.

Some states expect coaches to meet additional standards of care. Check with your athletic director to find out if your state has specific guidelines for the quality of care to be provided by coaches.

You should become familiar with each of these 9 legal duties. The first 8 duties deal mainly with preventive measures, which are explained more thoroughly in chapter 2. This book is primarily designed to help you handle duty number 9.

Parental Expectations

Parents will look to you for direction when their child is injured. They may ask questions such as these:

What do you think is wrong with my child's knee?

Will it get worse if my child continues playing?

Should my child see a doctor?

Does my child need to wear protective knee braces for football?

Will taping help prevent my child from reinjuring the ankle?

When can my child start competing again?

While you can't have all the answers, it helps to know those who can. That's where the other athletic health care team members can help. Let's look at the other members of the team, their roles, and your roles in interacting with them.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Learn how to assess and prevent heat-related illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range.

Prevention of Exertional Heat-Related Illnesses

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range. Here's how:

Monitor weather conditions and adjust practices accordingly. Table 11.1 shows the specific air temperature and humidity percentages that can be hazardous. Keep in mind, however that football exertional heat-related deaths have occurred at temperatures as low as 82 degrees with a relative humidity index at only 40 percent. If heat and humidity are equal to or higher than these conditions, make sure athletes are acclimated to the weather and are wearing light practice clothing. Schedule practices for early morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day.

Acclimate athletes to exercising in high heat and humidity. If you are located in a warm-weather climate or have practices during the summer, athletes need time (approximately 7 to 10 days) to adjust to high heat and humidity. During this time, hold short practices at low to moderate activity levels and provide fluid and rest breaks every 15 to 20 minutes. The National Athletic Trainers' Association 2009 Consensus Statement offers more specific guidelines for acclimating high school athletes to hot environmental conditions. Table 11.2 summarizes the organization's recommendations.

Switch to light clothing and less equipment. Athletes stay cooler if they wear shorts, white T-shirts, and less equipment (especially helmets and pads). Equipment blocks the ability of sweat to evaporate. It's especially important for athletes to wear light clothing and minimal equipment while they are acclimating to the heat.

Identify and monitor athletes who are prone to heat illness. Athletes who have previously suffered a heat illness and those with the sickle cell trait are particularly prone to exertional heat illness and should be continuously monitored during activity. Dehydrated, overweight, heavily muscled, or deconditioned athletes are at risk, as well as athletes taking certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, some asthma medications, certain supplements, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications). Closely monitor these athletes and make sure they drink plenty of fluids. Rest dehydrated athletes until they have become rehydrated (see next bullet for more information on adequate hydration).

The signs and symptoms of dehydration include

- thirst,

- flushed skin,

- fatigue,

- muscle cramps,

- apathy,

- dry lips and mouth,

- dark colored urine (should be clear or light yellow), and

- feeling weak.

Strictly enforce adequate hydration.Athletes can lose a great deal of water through sweat. If this fluid is not replaced, the body will have less water to cool itself and will become dehydrated. Dehydration not only increases athletes' risk for heat illness, it also decreases their performance. In fact, athletic performance may worsen after only 2 percent of the body weight is lost through sweat. For example, dehydrated athletes may experience

- decreased muscle strength,

- increased fatigue,

- decreased mental function (e.g., concentration), and

- decreased endurance.

Don't rely on athletes to drink enough fluids on their own. Most won't actually feel thirsty until they've lost 3 percent or more of their body weight in sweat (water). By that time their performance will have started to decrease and their risk of exertional heat illness will have increased. Also, they may not drink enough fluid to replenish the water lost through sweat.

For proper hydration, the National Athletic Trainers' Association (Casa et al. 2000) recommends

- 17 to 20 fluid ounces of fluid at least 2 hours before workouts, practice, or competition;

- another 7 to 10 fluid ounces of water or sports drink 10 to 15 minutes before workouts, practice, or competition;

- as a general guideline, 7 to 10 fluid ounces of cool (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) water or sports drink every 10 to 20 minutes during workouts, practice, or competition; and

- after workouts, practices, and competitions, 24 fluid ounces of water or sports drink for every pound of fluid lost through sweat (Manore et al. 2000).

- To determine the amount of weight lost through sweat, weigh athletes in their underwear before and after practices and competitions that take place in high heat and humidity.

Replenish electrolytes lost through sweat. During activities lasting longer than 45 to 50 minutes, substantial amounts of electrolytes such as sodium (salt) and potassium are lost in sweat. They are used in muscle contraction, fluid balance, and other body functions, and therefore must be replaced. In addition, sodium plays a role in activating the body's thirst mechanism, so it can stimulate athletes to drink (keep hydrated). The best way for athletes to replace these nutrients is by drinking a sports beverage (containing sodium) and eating a normal diet. Athletes can also replace sodium by lightly salting their food, so salt tablets are not recommended. Just a small amount of potassium is lost in sweat. Oranges and bananas are good sources of potassium.

Prohibit the use of sweatboxes, vinyl suits, diuretics, or other artificial means of quick weight reduction.The NFHS Wrestling Rules Committee has already prohibited these methods.

Identifying and Treating Exertional Heat Illnesses

During physical activity, the body can produce 10 to 20 times the amount of heat that it produces at rest (metabolism). Approximately 75 percent of this heat must be eliminated. If the air temperature is less than the body temperature, radiation, conduction, and convection can help dissipate 65 to 75 percent of this heat. However, if the air temperature is near the body temperature, these modes of heat loss are less effective, and the body has to rely more on perspiration. High humidity reduces the amount of sweat evaporation, and thus leaves exercising athletes at risk of exertional heat illness.

The following sections will cover three types of exertional heat illness:

- Heat cramps

- Heat exhaustion

- Heatstroke

Each has different signs and symptoms, as well as different first aid interventions. Heatstroke is life threatening, whereas heat exhaustion and heat cramps typically are not. Therefore, it is important that you learn to evaluate the signs and symptoms and learn to apply the first aid techniques that are appropriate for each illness.

Save

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

What to do if an athlete has a head injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Athlete With a Head Injury

If an athlete has suffered a blow to the head or a whipping of the head and neck, immediately evaluate for symptoms and signs of injury.

Causes

- Direct blow to the head

- Sudden, forceful jarring or whipping of the head

Ask if Experiencing Symptoms

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Ringing in the ears

- Grogginess

- Nausea

- Blurred or double vision

Check for Signs

- Confusion

- Unsteadiness

- Inability to multitask (unable to do several athletic skills at once or do a skill correctly when distracted)

- Short-term memory loss

- Emotional changes such as a short temper or depression

- Unresponsiveness to touch or voice (call out the athlete's name and tap on the shoulder)

- Irregular breathing

- Bleeding or a wound at the point of the blow

- Blood or fluid leaking from the mouth, nose, or ears

- Arm or leg weakness or numbness

- Neck pain with a decrease in motion

- Bump or deformity at the point of the blow

- Convulsions

- Abnormalities in pupils (unequal in size or failure to constrict to light)

- Vomiting

First Aid

If an athlete exhibits any of the previously listed signs or symptoms, pull the athlete out of activity. Symptoms such as headache or ringing in the ears may be the early signs of a more serious injury. In these cases, do the following:

- Continue to monitor the athlete and alert emergency medical services if signs and symptoms worsen.

- Immediately contact the parent or guardian and have them take the athlete to a physician.

- Give the parent or guardian a checklist of signs and symptoms to monitor.

For injuries with more severe signs such as confusion, unsteadiness, vomiting, convulsions, increasing headaches, increasing irritability, unusual behavior, arm or leg weakness or numbness, neck pain with a decrease in motion, pupil abnormalities, or unconsciousness, do the following:

- Immediately call emergency medical services.

- Stabilize the head and neck until EMS takes over. Leave an athlete's helmet on when stabilizing the head and neck. You don't want to jar the head or neck unnecessarily. This is especially true if the athlete is also wearing shoulder pads.

- Monitor the athlete for breathing difficulty and perform CPR if necessary.

- Control any profuse bleeding but avoid applying excess pressure over a head wound.

- Monitor for shock and treat as needed.

- Immobilize any fractures or unstable injuries as long as it does not jostle the athlete, which may worsen his or her condition.

Playing Status

When can an athlete return to a sport after a brain injury? In most cases, this decision has already been decided for you. Check your state law or the regulations of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) to ensure that your athletes are receiving mandated care and supervision. The NFHS prohibits athletes from returning to activity until examined and released by a physician. Many states are enacting laws with similar or stricter guidelines. Check your state for specific laws regarding brain injuries in athletes.

Prevention

- Educate yourself, your athletes, and their parents or guardians about concussions. Visit the CDC website at www.cdc.gov.

- During preseason physicals, screen for any history of head, spine, or nerve injuries. Have these athletes cleared by a physician, preferably a neurologist, before allowing them to participate.

- Use preseason brain testing. Numerous software programs or testing contractors can assess each athlete's normal brain function, including memory, cognitive functioning, motor (muscle and balance) control, and other functions before the beginning of a sport season. This information is then used as a baseline from which an athlete's brain function can be compared when an injury is suspected or has occurred. Doctors and athletic trainers can monitor this information while the athlete recovers and determine when an athlete is ready to progressively return to activity. These tests can also be used to monitor the athlete for any signs of decreasing brain function as he or she progresses back into full participation. A decrease in function signals that the athlete is not ready to proceed further and may need to actually decrease activity. This type of testing can be an important tool for you, your athletes, and their physicians in helping to more objectively determine the severity of a brain injury, the level of recovery, and the athlete's readiness to return to activity.

- Incorporate neck strengthening exercises into your preseason and in-season conditioning programs. These can be done simply by providing resistance to the head with a hand against all of its normal movements.

For sports requiring helmets, ensure the following:

- Helmets are regularly checked for damage and replaced if necessary.

- Older helmets are regularly replaced.

- Helmets are properly fitted to each athlete.

- Athletes are instructed in effectively securing helmets in place. A well-fitted helmet isn't effective if chin straps are not snapped and snug.

- Athletes are repeatedly reminded not to use the top of the helmet as a point of contact when tackling or checking another player or lowering the head just before contacting another athlete. Enforce this rule as necessary by sidelining offending athletes and reinforcing proper technique.

- Prohibit diving into water less than 6 feet deep.

- Train and use spotters at all times during gymnastics and cheerleading.

- Monitor athletes for signs or symptoms of head injury.

- Educate athletes about the signs and symptoms of head injuries. Encourage athletes to report signs of suspected brain injury in teammates. Consider providing some sort of recognition to these athletes in order to encourage reporting.

Learn more about Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition.

Defining a coach's role on the Athletics Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Coach's Role on the Athletic Health Care Team

As a coach you are likely to be involved in each portion of the athletic health care relay—prevention, recognition and first aid care, assessment and treatment, and rehabilitation.

Your roles are defined by

- certain rules of the legal system and rules of your school administration,

- expectations of parents, and

- interactions with other athletic health care team members.

Legal Definitions of Your Role

Basically, the legal system supports the theory that a coach's primary role is to minimize the risk of injury to the athletes under the coach's supervision. This encompasses a variety of duties.

1. Properly plan the activity.

- Teach the skills of the sport in the correct progression.

- Consider each athlete's developmental level and current physical condition. Evaluate your athletes' physical capacity and skill level with preseason fitness tests, and develop practice plans accordingly.

- Keep written records of fitness test results and practice plans. Don't deviate from your plans without good cause.

2. Provide proper instruction.

- Make sure that athletes are in proper condition to participate.

- Teach athletes the rules and the correct skills and strategies of the sport. For example, in football teach athletes that tackling with the head (spearing) is illegal and also a potentially dangerous technique.

- Teach athletes the sport skills and conditioning exercises in a progression so that the athletes are adequately prepared to handle more difficult skills or exercises.

- Keep up-to-date on better and safer ways of performing the techniques used in the sport.

- Provide competent and responsible assistants. If you have coaching assistants, make sure that they are knowledgeable in the skills and strategies of the sport and act in a mature and responsible manner.

3. Warn of inherent risks.

- Provide parents and athletes with both oral and written statements of the inherent health risks of their particular sport.

- Also warn athletes about potentially harmful conditions, such as playing conditions, dangerous or faulty equipment, and the like.

4. Provide a safe physical environment.

- Monitor current environmental conditions (i.e., windchill, temperature, humidity, and severe weather warnings).

- Periodically inspect the playing areas, the locker room, the weight room, and the dugout for hazards.

- Remove all hazards.

- Prevent improper or unsupervised use of facilities.

5. Provide adequate and proper equipment.

- Make sure athletes are using equipment that provides the maximum amount of protection against injury.

- Inspect equipment regularly.

- Teach athletes how to fit, use, and inspect their equipment.

6. Match your athletes appropriately.

- Match the athletes according to size, physical maturity, skill level, and experience.

- Do not pit physically immature or novice athletes against those who are in top condition and are highly skilled.

7. Evaluate athletes for injury or incapacity.

- Require all athletes to submit to preseason physicals and screenings to detect potential health problems.

- Withhold an athlete from practice and competition if the athlete is unable to compete without pain or loss of function (e.g., inability to walk, run, jump, throw, and so on without restriction).

8. Supervise the activity closely.

- Do not allow athletes to practice difficult or potentially dangerous skills without proper supervision.