- Home

- Anatomy

- Physical Therapy/Physiotherapy

- Massage Therapy

- Health Care in Exercise and Sport

- Postural Correction

Postural Correction presents 30 of the most commonly occurring postural conditions in a comprehensive format, providing hands-on therapists and body workers the knowledge and resources to help clients address their malalignments. Focusing on treatment rather than assessment, it takes a direct approach and applies specific techniques to improve posture from an anatomical rather than aesthetic perspective.

Primarily concerned with the lengthening of shortened tissues to help realign body parts, Postural Correction offers a collective approach to remedying malalignment. Techniques vary for each posture correction, including deep tissue massage, simple passive stretches, soft tissue release, common trigger points, and gentle limb traction. Because weak or poorly functioning muscles may contribute to postural problems, the text notes what muscles need to be strengthened and includes recommendations on techniques. Suggestions also are made for those postures that are difficult to correct with hands-on techniques, such as scoliosis, genu valgum (knock knees), and genu varum (bow legs).

Recognizing that the work clients can carry out independently is a crucial component of long-term postural correction, this guide includes information on how clients can continue their therapy independently between or at the conclusion of their therapy sessions. Therapists can take these techniques and recommendations to advise, educate, and guide clients in their efforts. Much attention is paid to lifestyle, activities, and habitual use or resting of a body part that may have led to the initial pain and malalignment.

Structured by anatomical regions of the body to make accessing information quick and easy, Postural Correction tackles postural concerns commonly affecting the spine; pelvis; upper limbs, including the shoulder and elbow; and lower limbs, including the hip, knee, ankle, and foot. Examples from various sports and demographics such as the elderly offer contextual and applied value. Descriptions avoid biomechanical jargon and instead focus on simple, clear explanations. Information is also included for when hands-on techniques are limited in correcting a particular posture.

Special features make this book unique and useful:

• Full-color anatomical illustrations and photographs present a clear visual of what will help bring about postural change.

• Consistency with the other titles in the Hands-On Guides for Therapists series ensures that the manual therapies throughout this book are easily accessible.

• An overview of each malalignment includes the muscles that are shortened or lengthened, notes about each posture, a bulleted list of ideas grouped according to whether these are carried out by the therapist or the client, and rationale for the suggested corrective techniques.

• Concluding comments summarize the information for access at a glance.

Earn continuing education credits/units! A continuing education course and exam that uses this book is also available. It may be purchased separately or as part of a package that includes all the course materials and exam.

Part I. Getting Started With Postural Correction

Chapter 1. Introduction to Postural Correction

Causes of Postural Malalignment

Consequences of Malalignment in the Body

Who Might Benefit From Postural Correction

Contraindications to and Cautions for Postural Correction

Closing Remarks

Chapter 2. Changing Posture

Determining Start of Postural Correction

Five Steps to Postural Correction

Techniques for Postural Correction

Aftercare

Gaining Rapport and Enhancing Engagement

Referral to Another Practitioner

Tailoring Your Treatments

Closing Remarks

Part II. Correcting the Spine

Chapter 3. Cervical Spine

Increased Lordosis

Lateral Neck Flexion

Forward Head Posture

Rotation of the Head and Neck

Closing Remarks

Chapter 4. Thoracic Spine

Kyphosis

Flatback

Rotated Thorax

Closing Remarks

Chapter 5. Lumbar Spine

Increased Lordosis

Decreased Lordosis

Closing Remarks

Chapter 6. Scoliosis

Types of Scoliosis

Closing Remarks

Part III. Correcting the Pelvis and Lower Limb

Chapter 7. Pelvis

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

Posterior Pelvic Tilt

Pelvic Rotation

Laterally Tilted Pelvis

Closing Remarks

Chapter 8. Lower Limb

Internal Rotation of Hip

Genu Recurvatum

Genu Flexum

Genu Varum

Genu Valgum

Tibial Torsion

Pes Planus

Pes Caves

Pes Valgus

Pes Varus

Closing Remarks

Part IV. Correcting the Shoulder and Upper Limb

Chapter 9. Shoulder

Protracted Scapula

Internal Rotation of Humerus

Winged Scapula

Elevated Shoulder

Closing Remarks

Chapter 10. Elbow

Flexed Elbow

Hyperextended Elbow

Closing Remarks

Jane Johnson, MSc, PhD, is a chartered physiotherapist and sport massage therapist specializing in occupational health and massage. In this role she spends much time assessing the posture of clients and examining whether work, sport, or recreational postures may be contributing to their symptoms. She devises postural correction plans that include both hands-on and hands-off techniques.

Johnson has taught continuing professional development (CPD) workshops for many organizations both in the UK and abroad. This experience has brought her into contact with thousands of therapists of all disciplines and informed her own practice. Johnson has a passion for inspiring and supporting students and newly qualified therapists to gain confidence in the use of assessment and treatment techniques.

Johnson is a member of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy and is registered with the Health Professions Council. A member of the Medico Legal Association of Chartered Physiotherapists, she provides expert witness reports on cases involving soft tissue therapies. Johnson is the author of six titles in the Hands-On Guides for Therapists series. These are, Postural Assessment, Postural Correction, Therapeutic Stretching, Soft Tissue Release, Deep Tissue Massage and Soft Tissue and Trigger Point Release. Postural Assessment has sold over 10,000 copies. She is also the author of The Big Back Book: Tips & Tricks for Therapists.

Jane regularly delivers webinars on popular musculoskeletal topics, as well as on life working as a therapist. In her Facebook group (Jane Johnson The Friendly Physio), she shares tips and tricks in her usual, friendly manner.

Johnson lives in the north of England in an unmodernized house where she creates books and webinars, makes art and rehomes big rescue dogs.

“An ideal instruction reference for students, therapists, and the non-specialist reader with an interest in postural correction issues. “Postural Correction” is as informative and educational as it is thoroughly ‘user friendly’ in content, tone, organization and presentation. “Postural Correction” is very highly recommended for professional, community, and academic library Health/Medicine instructional reference collections.”

--The Midwest Book Review

“Therapists will use different techniques for different clients and this book helps guide them through the possibilities. It also helps therapists think outside the box and approach clients in a different way, if one technique is not working. The photographs are very helpful… Having a book like this will help therapists take the skills they already have and apply some new theory and techniques to help their clients. The book is written at an appropriate level, not going into too much scientific detail that might be beyond the needs of some massage therapists. Yet, it still challenges therapists to approach their treatments differently.”

--Doody’s Book Review

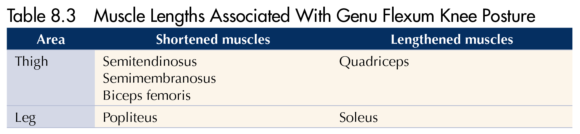

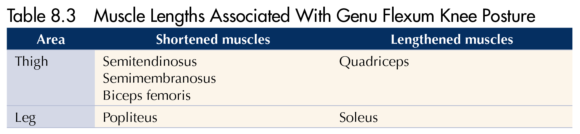

The Ins and Outs of Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods.

Genu Flexum

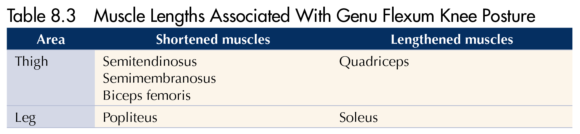

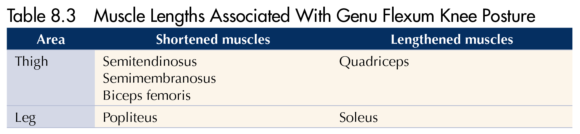

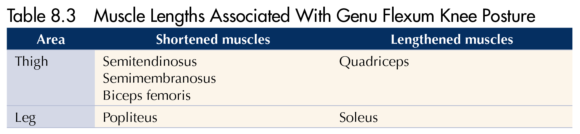

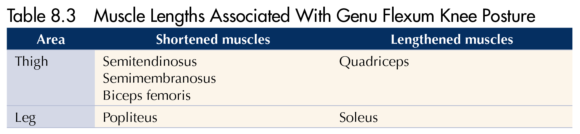

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods. Viewed laterally, an imaginary line drawn vertically from just anterior to the lateral malleolus bisects the tibia longitudinally in normal knee posture (figure 8.6a). In the genu flexum posture the knee itself falls anterior to this line, which no longer bisects the leg (figure 8.6b). This posture is best identified by viewing your client in the sagittal plane, as with the patient in figure 8.6c. Note the increased ankle dorsiflexion commonly associated with this posture.

|  |  |

Figure 8.6 Genu flexum posture: (a) normal knee alignment, (b) knee alignment in genu flexum, and (c) genu flexum of the right leg.

What You Can Do as a Therapist

Caution is needed when attempting to address genu flexum after knee surgery and when working with clients who use wheelchairs or spend much of their time in a chair, such as someone who might be frail or recovering from illness or injury. For each of the techniques suggested, consider whether deep pressure (as might be used when applying soft tissue release or addressing trigger points) is contraindicated for your client; ensure that your client has sufficient balance when performing any standing exercises.

- Recognize that intervention may be limited for clients where genu flexum results from abnormal high tone (e.g., spasticity associated with cerebral palsy).

- Passively release posterior knee tissues using myofascial release technique. This is an ideal technique to use for this posture where tissues on the back of the knee are tensed and pressure into the back of the knee must be avoided because of the presence of the popliteal artery and lymph nodes. A simple cross-hand technique could work well here, with one hand placed superior to the knee and one inferior to it.

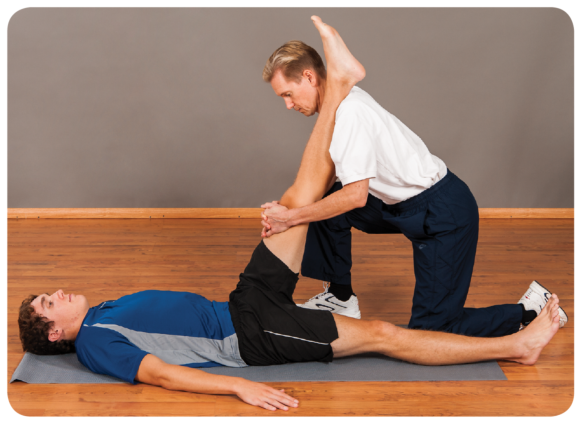

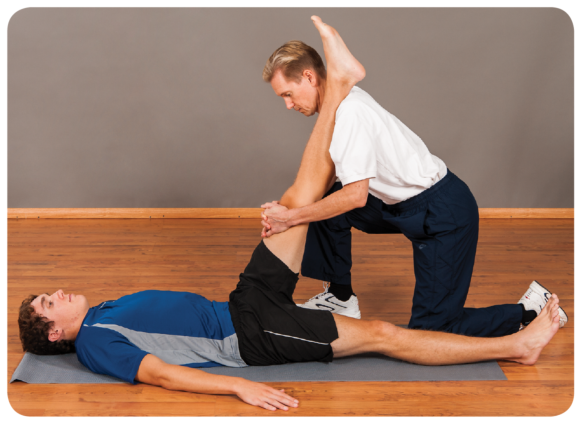

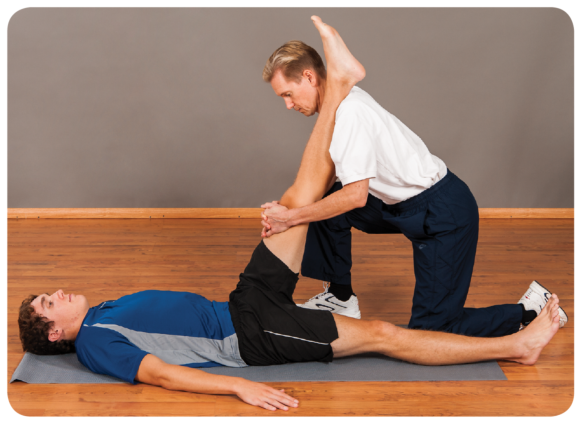

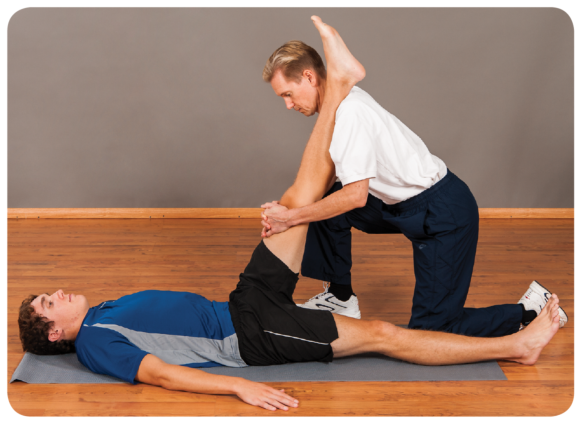

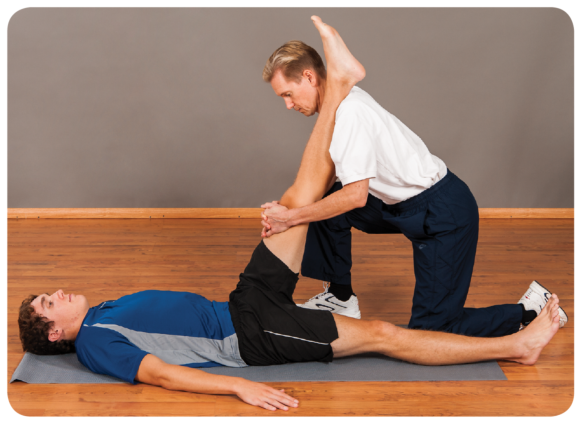

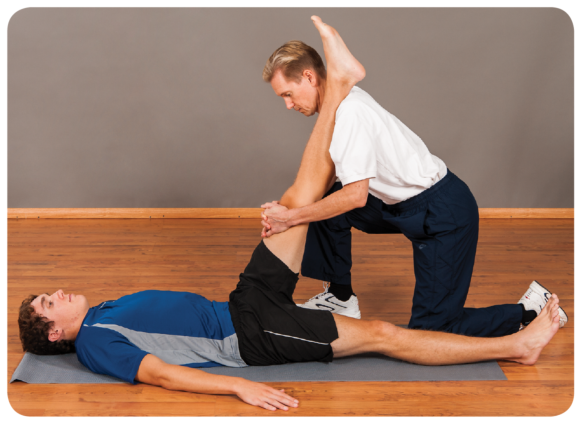

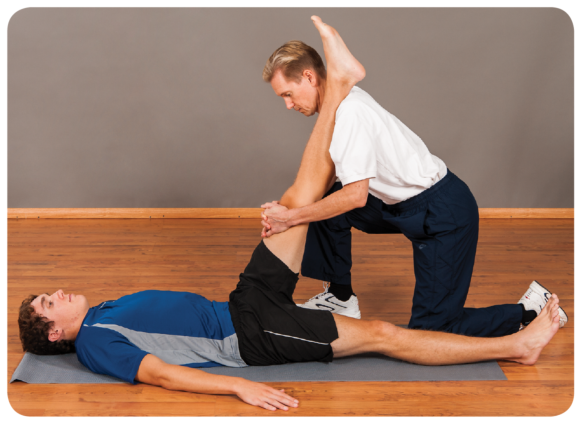

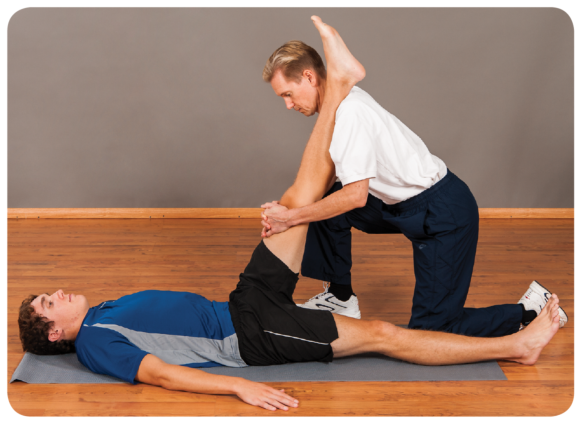

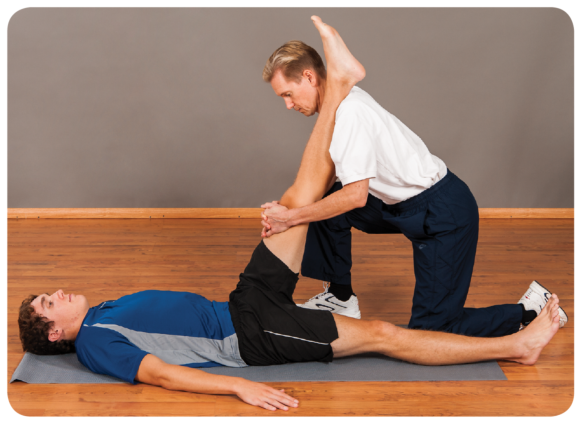

- Passively stretch shortened muscles, in this case hamstrings and soleus. There are many ways to do this, including simple stretches held at the end of the existing range (figure 8.7). One of the advantages of this simple supine hamstring stretch is that it can be performed with the knee flexed and, instead of passively flexing the hip at the end of range, ask your client to extend the knee. Contraction of quadriceps will facilitate relaxation of the hamstrings, increasing knee extension without the need for further hip flexion.

Figure 8.7 Therapist techniques for genu flexum include passive stretch of knee flexors.

- Apply massage to encourage a relaxation and lengthening of hamstrings and soleus. This could be deep tissue massage or soft tissue release to address tension you discover localized in specific tissues. Soft tissue release is useful here because it permits you to work within a range of knee flexion postures, stretching localized tissues only as far as is comfortable for your client.

- Treat any trigger points that you find in posterior tissues using localized static pressure and taking care not to press directly into the popliteal space.

- Genu flexum may be secondary to hip flexion (anterior tilt of the pelvis). If your assessments indicate an anteriorly tilted pelvis and shortened hip flexors, treat accordingly using the ideas put forward in chapter 7.

- Using the ideas set out in other sections of this book, treat the altered postures in other joints associated with genu flexum such as foot pronation, medial rotation of the hip, hip hitch and convexity of the spine.

What Your Client Can Do

- Rest in positions likely to stretch the posterior knee tissues. For example, using a footrest, the posterior knee is stretched through gravity (figure 8.8a). It is in the prone position, feet off the couch, and a light weight can be added to the ankle. Take care when using the prone position so as not to injure the front of the knee against the side of the couch or bed. This position is not suitable for clients with patellofemoral conditions when compression of the patella could be aggravating.

- Practice standing knee extension exercises using a stretchy band. Take care that the band is not too narrow because this could press into the back of the knee and cause pain. Active contraction of knee extensors in this manner encourages relaxation in the opposing muscle group, the knee flexors.

- Practice knee extension in supine (figure 8.8b). This is a good starting point for clients with pain or balance issues, for whom the previous exercise may be too demanding. Simply rest comfortably and attempt to press the back of the knee into the bed, floor or treatment couch. Some people place a bolster or small rolled-up towel beneath the ankle to provide leverage.

- Actively stretch the soleus muscle.

- Avoid prolonged sitting where possible unless it is with the legs outstretched and knees extended. If in a seated job, take short breaks and stand every hour to stretch the back of the leg.

- Active soft tissue release can be useful in addressing specific regions of tension in posterior thigh tissues; it is a technique that enables the client to self-treat the knee in flexion.

- Temporarily avoid sports that might perpetuate a flexed knee posture, such as rowing and cycling.

|  |

Figure 8.8 Client techniques for genu flexum include letting gravity stretch the posterior tissues in (a) sitting or (b) active knee extension in a supine position.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Posture through the Habituation Lens

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Identification and Avoidance of Causal Habits

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture. Is your client performing some activity in her occupation, sport or recreational activity that contributes to the perpetuation of this posture? In some cases a client may know what these behaviours are. For example, she may have realized that wearing high heels shortens calf muscles because when she wears flat-heeled shoes, she has pain or a stretching sensation in those muscles. In many cases a client may be unaware that a behaviour is aggravating a particular posture. For example, regularly using the same hand to carry a heavy bag or always slinging a rucksack over the same shoulder results in more frequent contraction of levator scapulae muscles on that shoulder than of the other shoulder.

In a random selection of 100 participants, Guimond and Massrieh (2012) found a correlation between a person's demeanour and posture (see table 2.3), supporting the notion that the body shapes itself into various postures depending on the underlying mental and emotional state. Grouping particpants according to the four postures described by Kendall and McCreary (1983), they used a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to determine characteristics of personality and discovered a relationship between posture type and two aspects of personality: extroversion and introversion. For example, they found that 96% of participants with 'perfect posture' were extrovert and only 4% were introvert, whereas the converse was true for participants with a kyphosis - lordosis posture, where only 17% were extrovert and 83% were introvert. This makes for slightly uncomfortable reading. If postural deviations are purely anatomical, manual correction of a joint or joints by either the client or a therapist is a good starting point in minimizing, eradicating or preventing an undesirable posture. There are enough variables to make this challenging. To add the variable of whether your client's personality might be correlated with posture raises many questions. For example, when attempting to correct the kyphosis - lordosis posture of your client, which Guimond and Massrieh found to correlate with the introverted personality type, would you be more successful if your client agreed to behave in a manner normally associated with extroversion? Can personality types be changed from introvert to extrovert, and would this affect posture?

There may, however, be a link between posture and emotion. Consider what happens to your own posture when you feel embarrassed, shy, ashamed, uncertain or withdrawn. Do you flex your spine, lower your head, flex your elbows, bring your hand to your mouth or jaw or hug yourself, making yourself physically smaller? Compare this to how your posture changes when you feel confident, certain and elated. Does your spine straighten, do you raise your head and do you pull back your shoulders? Changing how you feel affects muscle tone and overall posture, so the significance of the part played by your client in helping to correct his own posture - whether via physiological or emotional means - cannot be overemphasized.

Helping Your Client Identify, Eliminate or Reduce Causal Habits

- Use of pertinent questions during the subject stage of your assessment will help you identify factors that contribute to the posture that needs correction. A change in posture may be acute (e.g., an altered upper-limb posture after elbow fracture or altered neck or back posture associated with sudden spasm of a muscle), or it may be insidious (e.g., with progressive arthritis in the knee). Ask your client whether she regularly sustains a particular posture or regularly performs a repetitive action. These are likely to be contributing factors to imbalance in the body.

- Encourage your client to take an active part in the correction of posture.

- Encourage honest feedback. For example, did he do all of the exercises and stretches?

- Avoid overloading a client with too many stretches or exercises; instead, help him to focus on performing one or two correctly.

- Explain that, in some cases, correction can take weeks or months, depending on how long the body part has been out of alignment. In some cases correction may be readily attained, but what is important is sustained correction. Expecting gradual progress is probably a more realistic expectation than wanting immediate results.

- If you believe that some aspect of your client's work environment may be contributing to his posture, you may wish to refer him to the occupational health department of his organization, if there is one, or to an ergonomist. Factors affecting work-related musculoskeletal conditions are complex, and interventions require a tailored approach (Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2001). It seems reasonable that postural problems believed to have a work-related component are also likely to be complex and require an individualized approach.

- If your client has a job in which he remains seated at a computer, an ideal situation is for you to visit him and to assess how he is using the computer. Provide advice on basic computer setup and, if possible, follow the guidelines set forth in the appendix: Correct setup for display screen equipment to minimize postural stress in sitting. Give this advice to your client verbally and in printed form. Many sources of information are available for your client to refer to should he fall back into bad habits. Examples are Working With Display Screen Equipment (Health & Safety Executive 2013), How to Sit at a Computer (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2007), Perfect Posture (Chartered Society of Physiotherapists 2013) and Ergonomics Program: The Computer Workstation (National Institutes of Health 2014).

- Discourage reliance on your intervention in the long term. Hopefully, you will work with your client to help him correct a certain posture, and in doing so he will become aware of poor postural habits. Many professional sources are available for tips on postural correction, such as the American Chiropractic Association (2014). Your client may turn to these for gentle reminders on sitting, standing and sleeping postures in general.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Find Out Who Benefits from Postural Correction

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Who Might Benefit From Postural Correction?

The 30 postures described in Postural Correction are not specific to any one population, and many clients are likely to benefit from advice on avoiding or correcting postures that are likely to cause unwanted symptoms. The following list is not exhaustive but provides examples of the kinds of clients who may be susceptible to malalignment and for whom postural correction may be beneficial:

- Elderly people are more likely to present with genu valgum or genu varum when they are in the advanced stages of osteoarthritis. These postures can also be seen in people who have suffered knee injury or where injury or pathology affects the hips or ankles.

- The elderly are frequently observed to have kyphotic thoracic spines. So too are people who sit for prolonged periods or whose occupations involve repeated stooping.

- Many manual workers have asymmetric postures. For example, in the days when refuse bins were carried and emptied manually, refuse collectors portrayed lateral flexion of the spine as they repeatedly contracted muscles on one side in order to pick up and transport a dustbin. Whether such a working posture develops into true postural change is unknown but provides a good example of an activity that could lead to postural imbalance. Lateral flexion of the spine can also be observed in anyone who repeatedly carries a heavy bag on one side of the body. Vehicle-based camera crews filming sporting events have to look upwards to television screens for long periods, and at rest they may be observed to have hyperextension of the cervical spine. This is also common in linesmen employed to maintain overhead electrical cables, a job that necessitates climbing telegraph poles or using mobile elevated platforms whilst looking upwards. People with certain medical conditions are predisposed to malalignment. For example, hypermobile people lack stability in their joints and are likely to suffer increased cervical lordosis due to spondylolisthesis. Scoliosis is seen in 30% to 50% of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type; 23.7% have thoracic kyphosis and 43% to 55% have acquired flatfoot, and genu valgum often results from this foot posture (Tinkle 2008). In a study of 30 female teenagers with Down's syndrome, Dehghani and colleagues (2012) report the following percentages relating to specific postures: flatfoot (96%), genu valgum (83%), increased lumbar lordosis (63%), torticollis (lateral neck flexion) (60%), genu recurvatum (43%), kyphosis (10%), scoliosis (6%) and genu varum (3%).

- People who sustain injury to a joint may undergo a change in the posture of that joint, something that may be exacerbated through weight bearing. People who sustain injury during childhood sometimes develop marked asymmetrical postures in the lower limb and spine as they avoided bearing weight on the injured side. In some cases they never develop weight bearing equally through both lower limbs and show an unconscious preference for the uninjured side, despite having recovered many years previously from the initial injury.

- Non-symmetrical cervical postures may be observed in some people after whiplash injury.

- Pregnant women often appear to have increased lordotic lumbar spines, in which the spine is pulled forward due to the additional weight carried anteriorly.

- In addition to the postures described by Bloomfield and colleagues, in table 1.2 you can observe specific postures in sportspeople:

- The upper fibres of the trapezius muscles in tennis players tend to hypertrophy on the dominant side due to repeated elevation of the batting arm above shoulder height. The scapula on the dominant side of asymptomatic tennis players has been found to be more protracted than the scapula on the non-dominant side, and this asymmetry may be normal for this group of sportspeople (Oyama et al. 2008).

- Golfers may develop postures associated with rotation not just in the back and hips but at the knees and feet also.

- Boxers may have elbows that are flexed at rest due to hypertrophy and shortening of the elbow flexor muscles.

- Practitioners of wing chun kung fu frequently demonstrate internal rotation of both the hips and shoulders. This is because of the stance adopted for practicing many of the chi saus, the repetitive arm movements inherent to this form of martial art.

- Postural problems also develop in association with immobility:

- People who work at desks often display internal rotation of the shoulders and thoracic kyphosis due to prolonged sitting postures.

- People who use wheelchairs or who spend many hours sitting or driving as part of their occupation may develop postures associated with hip and knee flexion.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

The Ins and Outs of Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods.

Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods. Viewed laterally, an imaginary line drawn vertically from just anterior to the lateral malleolus bisects the tibia longitudinally in normal knee posture (figure 8.6a). In the genu flexum posture the knee itself falls anterior to this line, which no longer bisects the leg (figure 8.6b). This posture is best identified by viewing your client in the sagittal plane, as with the patient in figure 8.6c. Note the increased ankle dorsiflexion commonly associated with this posture.

|  |  |

Figure 8.6 Genu flexum posture: (a) normal knee alignment, (b) knee alignment in genu flexum, and (c) genu flexum of the right leg.

What You Can Do as a Therapist

Caution is needed when attempting to address genu flexum after knee surgery and when working with clients who use wheelchairs or spend much of their time in a chair, such as someone who might be frail or recovering from illness or injury. For each of the techniques suggested, consider whether deep pressure (as might be used when applying soft tissue release or addressing trigger points) is contraindicated for your client; ensure that your client has sufficient balance when performing any standing exercises.

- Recognize that intervention may be limited for clients where genu flexum results from abnormal high tone (e.g., spasticity associated with cerebral palsy).

- Passively release posterior knee tissues using myofascial release technique. This is an ideal technique to use for this posture where tissues on the back of the knee are tensed and pressure into the back of the knee must be avoided because of the presence of the popliteal artery and lymph nodes. A simple cross-hand technique could work well here, with one hand placed superior to the knee and one inferior to it.

- Passively stretch shortened muscles, in this case hamstrings and soleus. There are many ways to do this, including simple stretches held at the end of the existing range (figure 8.7). One of the advantages of this simple supine hamstring stretch is that it can be performed with the knee flexed and, instead of passively flexing the hip at the end of range, ask your client to extend the knee. Contraction of quadriceps will facilitate relaxation of the hamstrings, increasing knee extension without the need for further hip flexion.

Figure 8.7 Therapist techniques for genu flexum include passive stretch of knee flexors.

- Apply massage to encourage a relaxation and lengthening of hamstrings and soleus. This could be deep tissue massage or soft tissue release to address tension you discover localized in specific tissues. Soft tissue release is useful here because it permits you to work within a range of knee flexion postures, stretching localized tissues only as far as is comfortable for your client.

- Treat any trigger points that you find in posterior tissues using localized static pressure and taking care not to press directly into the popliteal space.

- Genu flexum may be secondary to hip flexion (anterior tilt of the pelvis). If your assessments indicate an anteriorly tilted pelvis and shortened hip flexors, treat accordingly using the ideas put forward in chapter 7.

- Using the ideas set out in other sections of this book, treat the altered postures in other joints associated with genu flexum such as foot pronation, medial rotation of the hip, hip hitch and convexity of the spine.

What Your Client Can Do

- Rest in positions likely to stretch the posterior knee tissues. For example, using a footrest, the posterior knee is stretched through gravity (figure 8.8a). It is in the prone position, feet off the couch, and a light weight can be added to the ankle. Take care when using the prone position so as not to injure the front of the knee against the side of the couch or bed. This position is not suitable for clients with patellofemoral conditions when compression of the patella could be aggravating.

- Practice standing knee extension exercises using a stretchy band. Take care that the band is not too narrow because this could press into the back of the knee and cause pain. Active contraction of knee extensors in this manner encourages relaxation in the opposing muscle group, the knee flexors.

- Practice knee extension in supine (figure 8.8b). This is a good starting point for clients with pain or balance issues, for whom the previous exercise may be too demanding. Simply rest comfortably and attempt to press the back of the knee into the bed, floor or treatment couch. Some people place a bolster or small rolled-up towel beneath the ankle to provide leverage.

- Actively stretch the soleus muscle.

- Avoid prolonged sitting where possible unless it is with the legs outstretched and knees extended. If in a seated job, take short breaks and stand every hour to stretch the back of the leg.

- Active soft tissue release can be useful in addressing specific regions of tension in posterior thigh tissues; it is a technique that enables the client to self-treat the knee in flexion.

- Temporarily avoid sports that might perpetuate a flexed knee posture, such as rowing and cycling.

|  |

Figure 8.8 Client techniques for genu flexum include letting gravity stretch the posterior tissues in (a) sitting or (b) active knee extension in a supine position.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Posture through the Habituation Lens

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Identification and Avoidance of Causal Habits

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture. Is your client performing some activity in her occupation, sport or recreational activity that contributes to the perpetuation of this posture? In some cases a client may know what these behaviours are. For example, she may have realized that wearing high heels shortens calf muscles because when she wears flat-heeled shoes, she has pain or a stretching sensation in those muscles. In many cases a client may be unaware that a behaviour is aggravating a particular posture. For example, regularly using the same hand to carry a heavy bag or always slinging a rucksack over the same shoulder results in more frequent contraction of levator scapulae muscles on that shoulder than of the other shoulder.

In a random selection of 100 participants, Guimond and Massrieh (2012) found a correlation between a person's demeanour and posture (see table 2.3), supporting the notion that the body shapes itself into various postures depending on the underlying mental and emotional state. Grouping particpants according to the four postures described by Kendall and McCreary (1983), they used a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to determine characteristics of personality and discovered a relationship between posture type and two aspects of personality: extroversion and introversion. For example, they found that 96% of participants with 'perfect posture' were extrovert and only 4% were introvert, whereas the converse was true for participants with a kyphosis - lordosis posture, where only 17% were extrovert and 83% were introvert. This makes for slightly uncomfortable reading. If postural deviations are purely anatomical, manual correction of a joint or joints by either the client or a therapist is a good starting point in minimizing, eradicating or preventing an undesirable posture. There are enough variables to make this challenging. To add the variable of whether your client's personality might be correlated with posture raises many questions. For example, when attempting to correct the kyphosis - lordosis posture of your client, which Guimond and Massrieh found to correlate with the introverted personality type, would you be more successful if your client agreed to behave in a manner normally associated with extroversion? Can personality types be changed from introvert to extrovert, and would this affect posture?

There may, however, be a link between posture and emotion. Consider what happens to your own posture when you feel embarrassed, shy, ashamed, uncertain or withdrawn. Do you flex your spine, lower your head, flex your elbows, bring your hand to your mouth or jaw or hug yourself, making yourself physically smaller? Compare this to how your posture changes when you feel confident, certain and elated. Does your spine straighten, do you raise your head and do you pull back your shoulders? Changing how you feel affects muscle tone and overall posture, so the significance of the part played by your client in helping to correct his own posture - whether via physiological or emotional means - cannot be overemphasized.

Helping Your Client Identify, Eliminate or Reduce Causal Habits

- Use of pertinent questions during the subject stage of your assessment will help you identify factors that contribute to the posture that needs correction. A change in posture may be acute (e.g., an altered upper-limb posture after elbow fracture or altered neck or back posture associated with sudden spasm of a muscle), or it may be insidious (e.g., with progressive arthritis in the knee). Ask your client whether she regularly sustains a particular posture or regularly performs a repetitive action. These are likely to be contributing factors to imbalance in the body.

- Encourage your client to take an active part in the correction of posture.

- Encourage honest feedback. For example, did he do all of the exercises and stretches?

- Avoid overloading a client with too many stretches or exercises; instead, help him to focus on performing one or two correctly.

- Explain that, in some cases, correction can take weeks or months, depending on how long the body part has been out of alignment. In some cases correction may be readily attained, but what is important is sustained correction. Expecting gradual progress is probably a more realistic expectation than wanting immediate results.

- If you believe that some aspect of your client's work environment may be contributing to his posture, you may wish to refer him to the occupational health department of his organization, if there is one, or to an ergonomist. Factors affecting work-related musculoskeletal conditions are complex, and interventions require a tailored approach (Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2001). It seems reasonable that postural problems believed to have a work-related component are also likely to be complex and require an individualized approach.

- If your client has a job in which he remains seated at a computer, an ideal situation is for you to visit him and to assess how he is using the computer. Provide advice on basic computer setup and, if possible, follow the guidelines set forth in the appendix: Correct setup for display screen equipment to minimize postural stress in sitting. Give this advice to your client verbally and in printed form. Many sources of information are available for your client to refer to should he fall back into bad habits. Examples are Working With Display Screen Equipment (Health & Safety Executive 2013), How to Sit at a Computer (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2007), Perfect Posture (Chartered Society of Physiotherapists 2013) and Ergonomics Program: The Computer Workstation (National Institutes of Health 2014).

- Discourage reliance on your intervention in the long term. Hopefully, you will work with your client to help him correct a certain posture, and in doing so he will become aware of poor postural habits. Many professional sources are available for tips on postural correction, such as the American Chiropractic Association (2014). Your client may turn to these for gentle reminders on sitting, standing and sleeping postures in general.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Find Out Who Benefits from Postural Correction

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Who Might Benefit From Postural Correction?

The 30 postures described in Postural Correction are not specific to any one population, and many clients are likely to benefit from advice on avoiding or correcting postures that are likely to cause unwanted symptoms. The following list is not exhaustive but provides examples of the kinds of clients who may be susceptible to malalignment and for whom postural correction may be beneficial:

- Elderly people are more likely to present with genu valgum or genu varum when they are in the advanced stages of osteoarthritis. These postures can also be seen in people who have suffered knee injury or where injury or pathology affects the hips or ankles.

- The elderly are frequently observed to have kyphotic thoracic spines. So too are people who sit for prolonged periods or whose occupations involve repeated stooping.

- Many manual workers have asymmetric postures. For example, in the days when refuse bins were carried and emptied manually, refuse collectors portrayed lateral flexion of the spine as they repeatedly contracted muscles on one side in order to pick up and transport a dustbin. Whether such a working posture develops into true postural change is unknown but provides a good example of an activity that could lead to postural imbalance. Lateral flexion of the spine can also be observed in anyone who repeatedly carries a heavy bag on one side of the body. Vehicle-based camera crews filming sporting events have to look upwards to television screens for long periods, and at rest they may be observed to have hyperextension of the cervical spine. This is also common in linesmen employed to maintain overhead electrical cables, a job that necessitates climbing telegraph poles or using mobile elevated platforms whilst looking upwards. People with certain medical conditions are predisposed to malalignment. For example, hypermobile people lack stability in their joints and are likely to suffer increased cervical lordosis due to spondylolisthesis. Scoliosis is seen in 30% to 50% of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type; 23.7% have thoracic kyphosis and 43% to 55% have acquired flatfoot, and genu valgum often results from this foot posture (Tinkle 2008). In a study of 30 female teenagers with Down's syndrome, Dehghani and colleagues (2012) report the following percentages relating to specific postures: flatfoot (96%), genu valgum (83%), increased lumbar lordosis (63%), torticollis (lateral neck flexion) (60%), genu recurvatum (43%), kyphosis (10%), scoliosis (6%) and genu varum (3%).

- People who sustain injury to a joint may undergo a change in the posture of that joint, something that may be exacerbated through weight bearing. People who sustain injury during childhood sometimes develop marked asymmetrical postures in the lower limb and spine as they avoided bearing weight on the injured side. In some cases they never develop weight bearing equally through both lower limbs and show an unconscious preference for the uninjured side, despite having recovered many years previously from the initial injury.

- Non-symmetrical cervical postures may be observed in some people after whiplash injury.

- Pregnant women often appear to have increased lordotic lumbar spines, in which the spine is pulled forward due to the additional weight carried anteriorly.

- In addition to the postures described by Bloomfield and colleagues, in table 1.2 you can observe specific postures in sportspeople:

- The upper fibres of the trapezius muscles in tennis players tend to hypertrophy on the dominant side due to repeated elevation of the batting arm above shoulder height. The scapula on the dominant side of asymptomatic tennis players has been found to be more protracted than the scapula on the non-dominant side, and this asymmetry may be normal for this group of sportspeople (Oyama et al. 2008).

- Golfers may develop postures associated with rotation not just in the back and hips but at the knees and feet also.

- Boxers may have elbows that are flexed at rest due to hypertrophy and shortening of the elbow flexor muscles.

- Practitioners of wing chun kung fu frequently demonstrate internal rotation of both the hips and shoulders. This is because of the stance adopted for practicing many of the chi saus, the repetitive arm movements inherent to this form of martial art.

- Postural problems also develop in association with immobility:

- People who work at desks often display internal rotation of the shoulders and thoracic kyphosis due to prolonged sitting postures.

- People who use wheelchairs or who spend many hours sitting or driving as part of their occupation may develop postures associated with hip and knee flexion.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

The Ins and Outs of Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods.

Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods. Viewed laterally, an imaginary line drawn vertically from just anterior to the lateral malleolus bisects the tibia longitudinally in normal knee posture (figure 8.6a). In the genu flexum posture the knee itself falls anterior to this line, which no longer bisects the leg (figure 8.6b). This posture is best identified by viewing your client in the sagittal plane, as with the patient in figure 8.6c. Note the increased ankle dorsiflexion commonly associated with this posture.

|  |  |

Figure 8.6 Genu flexum posture: (a) normal knee alignment, (b) knee alignment in genu flexum, and (c) genu flexum of the right leg.

What You Can Do as a Therapist

Caution is needed when attempting to address genu flexum after knee surgery and when working with clients who use wheelchairs or spend much of their time in a chair, such as someone who might be frail or recovering from illness or injury. For each of the techniques suggested, consider whether deep pressure (as might be used when applying soft tissue release or addressing trigger points) is contraindicated for your client; ensure that your client has sufficient balance when performing any standing exercises.

- Recognize that intervention may be limited for clients where genu flexum results from abnormal high tone (e.g., spasticity associated with cerebral palsy).

- Passively release posterior knee tissues using myofascial release technique. This is an ideal technique to use for this posture where tissues on the back of the knee are tensed and pressure into the back of the knee must be avoided because of the presence of the popliteal artery and lymph nodes. A simple cross-hand technique could work well here, with one hand placed superior to the knee and one inferior to it.

- Passively stretch shortened muscles, in this case hamstrings and soleus. There are many ways to do this, including simple stretches held at the end of the existing range (figure 8.7). One of the advantages of this simple supine hamstring stretch is that it can be performed with the knee flexed and, instead of passively flexing the hip at the end of range, ask your client to extend the knee. Contraction of quadriceps will facilitate relaxation of the hamstrings, increasing knee extension without the need for further hip flexion.

Figure 8.7 Therapist techniques for genu flexum include passive stretch of knee flexors.

- Apply massage to encourage a relaxation and lengthening of hamstrings and soleus. This could be deep tissue massage or soft tissue release to address tension you discover localized in specific tissues. Soft tissue release is useful here because it permits you to work within a range of knee flexion postures, stretching localized tissues only as far as is comfortable for your client.

- Treat any trigger points that you find in posterior tissues using localized static pressure and taking care not to press directly into the popliteal space.

- Genu flexum may be secondary to hip flexion (anterior tilt of the pelvis). If your assessments indicate an anteriorly tilted pelvis and shortened hip flexors, treat accordingly using the ideas put forward in chapter 7.

- Using the ideas set out in other sections of this book, treat the altered postures in other joints associated with genu flexum such as foot pronation, medial rotation of the hip, hip hitch and convexity of the spine.

What Your Client Can Do

- Rest in positions likely to stretch the posterior knee tissues. For example, using a footrest, the posterior knee is stretched through gravity (figure 8.8a). It is in the prone position, feet off the couch, and a light weight can be added to the ankle. Take care when using the prone position so as not to injure the front of the knee against the side of the couch or bed. This position is not suitable for clients with patellofemoral conditions when compression of the patella could be aggravating.

- Practice standing knee extension exercises using a stretchy band. Take care that the band is not too narrow because this could press into the back of the knee and cause pain. Active contraction of knee extensors in this manner encourages relaxation in the opposing muscle group, the knee flexors.

- Practice knee extension in supine (figure 8.8b). This is a good starting point for clients with pain or balance issues, for whom the previous exercise may be too demanding. Simply rest comfortably and attempt to press the back of the knee into the bed, floor or treatment couch. Some people place a bolster or small rolled-up towel beneath the ankle to provide leverage.

- Actively stretch the soleus muscle.

- Avoid prolonged sitting where possible unless it is with the legs outstretched and knees extended. If in a seated job, take short breaks and stand every hour to stretch the back of the leg.

- Active soft tissue release can be useful in addressing specific regions of tension in posterior thigh tissues; it is a technique that enables the client to self-treat the knee in flexion.

- Temporarily avoid sports that might perpetuate a flexed knee posture, such as rowing and cycling.

|  |

Figure 8.8 Client techniques for genu flexum include letting gravity stretch the posterior tissues in (a) sitting or (b) active knee extension in a supine position.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Posture through the Habituation Lens

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Identification and Avoidance of Causal Habits

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture. Is your client performing some activity in her occupation, sport or recreational activity that contributes to the perpetuation of this posture? In some cases a client may know what these behaviours are. For example, she may have realized that wearing high heels shortens calf muscles because when she wears flat-heeled shoes, she has pain or a stretching sensation in those muscles. In many cases a client may be unaware that a behaviour is aggravating a particular posture. For example, regularly using the same hand to carry a heavy bag or always slinging a rucksack over the same shoulder results in more frequent contraction of levator scapulae muscles on that shoulder than of the other shoulder.

In a random selection of 100 participants, Guimond and Massrieh (2012) found a correlation between a person's demeanour and posture (see table 2.3), supporting the notion that the body shapes itself into various postures depending on the underlying mental and emotional state. Grouping particpants according to the four postures described by Kendall and McCreary (1983), they used a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to determine characteristics of personality and discovered a relationship between posture type and two aspects of personality: extroversion and introversion. For example, they found that 96% of participants with 'perfect posture' were extrovert and only 4% were introvert, whereas the converse was true for participants with a kyphosis - lordosis posture, where only 17% were extrovert and 83% were introvert. This makes for slightly uncomfortable reading. If postural deviations are purely anatomical, manual correction of a joint or joints by either the client or a therapist is a good starting point in minimizing, eradicating or preventing an undesirable posture. There are enough variables to make this challenging. To add the variable of whether your client's personality might be correlated with posture raises many questions. For example, when attempting to correct the kyphosis - lordosis posture of your client, which Guimond and Massrieh found to correlate with the introverted personality type, would you be more successful if your client agreed to behave in a manner normally associated with extroversion? Can personality types be changed from introvert to extrovert, and would this affect posture?

There may, however, be a link between posture and emotion. Consider what happens to your own posture when you feel embarrassed, shy, ashamed, uncertain or withdrawn. Do you flex your spine, lower your head, flex your elbows, bring your hand to your mouth or jaw or hug yourself, making yourself physically smaller? Compare this to how your posture changes when you feel confident, certain and elated. Does your spine straighten, do you raise your head and do you pull back your shoulders? Changing how you feel affects muscle tone and overall posture, so the significance of the part played by your client in helping to correct his own posture - whether via physiological or emotional means - cannot be overemphasized.

Helping Your Client Identify, Eliminate or Reduce Causal Habits

- Use of pertinent questions during the subject stage of your assessment will help you identify factors that contribute to the posture that needs correction. A change in posture may be acute (e.g., an altered upper-limb posture after elbow fracture or altered neck or back posture associated with sudden spasm of a muscle), or it may be insidious (e.g., with progressive arthritis in the knee). Ask your client whether she regularly sustains a particular posture or regularly performs a repetitive action. These are likely to be contributing factors to imbalance in the body.

- Encourage your client to take an active part in the correction of posture.

- Encourage honest feedback. For example, did he do all of the exercises and stretches?

- Avoid overloading a client with too many stretches or exercises; instead, help him to focus on performing one or two correctly.

- Explain that, in some cases, correction can take weeks or months, depending on how long the body part has been out of alignment. In some cases correction may be readily attained, but what is important is sustained correction. Expecting gradual progress is probably a more realistic expectation than wanting immediate results.

- If you believe that some aspect of your client's work environment may be contributing to his posture, you may wish to refer him to the occupational health department of his organization, if there is one, or to an ergonomist. Factors affecting work-related musculoskeletal conditions are complex, and interventions require a tailored approach (Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2001). It seems reasonable that postural problems believed to have a work-related component are also likely to be complex and require an individualized approach.

- If your client has a job in which he remains seated at a computer, an ideal situation is for you to visit him and to assess how he is using the computer. Provide advice on basic computer setup and, if possible, follow the guidelines set forth in the appendix: Correct setup for display screen equipment to minimize postural stress in sitting. Give this advice to your client verbally and in printed form. Many sources of information are available for your client to refer to should he fall back into bad habits. Examples are Working With Display Screen Equipment (Health & Safety Executive 2013), How to Sit at a Computer (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2007), Perfect Posture (Chartered Society of Physiotherapists 2013) and Ergonomics Program: The Computer Workstation (National Institutes of Health 2014).

- Discourage reliance on your intervention in the long term. Hopefully, you will work with your client to help him correct a certain posture, and in doing so he will become aware of poor postural habits. Many professional sources are available for tips on postural correction, such as the American Chiropractic Association (2014). Your client may turn to these for gentle reminders on sitting, standing and sleeping postures in general.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Find Out Who Benefits from Postural Correction

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Who Might Benefit From Postural Correction?

The 30 postures described in Postural Correction are not specific to any one population, and many clients are likely to benefit from advice on avoiding or correcting postures that are likely to cause unwanted symptoms. The following list is not exhaustive but provides examples of the kinds of clients who may be susceptible to malalignment and for whom postural correction may be beneficial:

- Elderly people are more likely to present with genu valgum or genu varum when they are in the advanced stages of osteoarthritis. These postures can also be seen in people who have suffered knee injury or where injury or pathology affects the hips or ankles.

- The elderly are frequently observed to have kyphotic thoracic spines. So too are people who sit for prolonged periods or whose occupations involve repeated stooping.

- Many manual workers have asymmetric postures. For example, in the days when refuse bins were carried and emptied manually, refuse collectors portrayed lateral flexion of the spine as they repeatedly contracted muscles on one side in order to pick up and transport a dustbin. Whether such a working posture develops into true postural change is unknown but provides a good example of an activity that could lead to postural imbalance. Lateral flexion of the spine can also be observed in anyone who repeatedly carries a heavy bag on one side of the body. Vehicle-based camera crews filming sporting events have to look upwards to television screens for long periods, and at rest they may be observed to have hyperextension of the cervical spine. This is also common in linesmen employed to maintain overhead electrical cables, a job that necessitates climbing telegraph poles or using mobile elevated platforms whilst looking upwards. People with certain medical conditions are predisposed to malalignment. For example, hypermobile people lack stability in their joints and are likely to suffer increased cervical lordosis due to spondylolisthesis. Scoliosis is seen in 30% to 50% of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type; 23.7% have thoracic kyphosis and 43% to 55% have acquired flatfoot, and genu valgum often results from this foot posture (Tinkle 2008). In a study of 30 female teenagers with Down's syndrome, Dehghani and colleagues (2012) report the following percentages relating to specific postures: flatfoot (96%), genu valgum (83%), increased lumbar lordosis (63%), torticollis (lateral neck flexion) (60%), genu recurvatum (43%), kyphosis (10%), scoliosis (6%) and genu varum (3%).

- People who sustain injury to a joint may undergo a change in the posture of that joint, something that may be exacerbated through weight bearing. People who sustain injury during childhood sometimes develop marked asymmetrical postures in the lower limb and spine as they avoided bearing weight on the injured side. In some cases they never develop weight bearing equally through both lower limbs and show an unconscious preference for the uninjured side, despite having recovered many years previously from the initial injury.

- Non-symmetrical cervical postures may be observed in some people after whiplash injury.

- Pregnant women often appear to have increased lordotic lumbar spines, in which the spine is pulled forward due to the additional weight carried anteriorly.

- In addition to the postures described by Bloomfield and colleagues, in table 1.2 you can observe specific postures in sportspeople:

- The upper fibres of the trapezius muscles in tennis players tend to hypertrophy on the dominant side due to repeated elevation of the batting arm above shoulder height. The scapula on the dominant side of asymptomatic tennis players has been found to be more protracted than the scapula on the non-dominant side, and this asymmetry may be normal for this group of sportspeople (Oyama et al. 2008).

- Golfers may develop postures associated with rotation not just in the back and hips but at the knees and feet also.

- Boxers may have elbows that are flexed at rest due to hypertrophy and shortening of the elbow flexor muscles.

- Practitioners of wing chun kung fu frequently demonstrate internal rotation of both the hips and shoulders. This is because of the stance adopted for practicing many of the chi saus, the repetitive arm movements inherent to this form of martial art.

- Postural problems also develop in association with immobility:

- People who work at desks often display internal rotation of the shoulders and thoracic kyphosis due to prolonged sitting postures.

- People who use wheelchairs or who spend many hours sitting or driving as part of their occupation may develop postures associated with hip and knee flexion.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

The Ins and Outs of Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods.

Genu Flexum

As the name indicates, in the genu flexum (flexed knee) posture a person bears weight through a knee that is flexed to a greater degree than is normal when standing. Less common than genu recurvatum, it is a posture observed in the elderly or in patients who have been sedentary and their knees have been allowed to rest in a flexed position for prolonged periods. Viewed laterally, an imaginary line drawn vertically from just anterior to the lateral malleolus bisects the tibia longitudinally in normal knee posture (figure 8.6a). In the genu flexum posture the knee itself falls anterior to this line, which no longer bisects the leg (figure 8.6b). This posture is best identified by viewing your client in the sagittal plane, as with the patient in figure 8.6c. Note the increased ankle dorsiflexion commonly associated with this posture.

|  |  |

Figure 8.6 Genu flexum posture: (a) normal knee alignment, (b) knee alignment in genu flexum, and (c) genu flexum of the right leg.

What You Can Do as a Therapist

Caution is needed when attempting to address genu flexum after knee surgery and when working with clients who use wheelchairs or spend much of their time in a chair, such as someone who might be frail or recovering from illness or injury. For each of the techniques suggested, consider whether deep pressure (as might be used when applying soft tissue release or addressing trigger points) is contraindicated for your client; ensure that your client has sufficient balance when performing any standing exercises.

- Recognize that intervention may be limited for clients where genu flexum results from abnormal high tone (e.g., spasticity associated with cerebral palsy).

- Passively release posterior knee tissues using myofascial release technique. This is an ideal technique to use for this posture where tissues on the back of the knee are tensed and pressure into the back of the knee must be avoided because of the presence of the popliteal artery and lymph nodes. A simple cross-hand technique could work well here, with one hand placed superior to the knee and one inferior to it.

- Passively stretch shortened muscles, in this case hamstrings and soleus. There are many ways to do this, including simple stretches held at the end of the existing range (figure 8.7). One of the advantages of this simple supine hamstring stretch is that it can be performed with the knee flexed and, instead of passively flexing the hip at the end of range, ask your client to extend the knee. Contraction of quadriceps will facilitate relaxation of the hamstrings, increasing knee extension without the need for further hip flexion.

Figure 8.7 Therapist techniques for genu flexum include passive stretch of knee flexors.

- Apply massage to encourage a relaxation and lengthening of hamstrings and soleus. This could be deep tissue massage or soft tissue release to address tension you discover localized in specific tissues. Soft tissue release is useful here because it permits you to work within a range of knee flexion postures, stretching localized tissues only as far as is comfortable for your client.

- Treat any trigger points that you find in posterior tissues using localized static pressure and taking care not to press directly into the popliteal space.

- Genu flexum may be secondary to hip flexion (anterior tilt of the pelvis). If your assessments indicate an anteriorly tilted pelvis and shortened hip flexors, treat accordingly using the ideas put forward in chapter 7.

- Using the ideas set out in other sections of this book, treat the altered postures in other joints associated with genu flexum such as foot pronation, medial rotation of the hip, hip hitch and convexity of the spine.

What Your Client Can Do

- Rest in positions likely to stretch the posterior knee tissues. For example, using a footrest, the posterior knee is stretched through gravity (figure 8.8a). It is in the prone position, feet off the couch, and a light weight can be added to the ankle. Take care when using the prone position so as not to injure the front of the knee against the side of the couch or bed. This position is not suitable for clients with patellofemoral conditions when compression of the patella could be aggravating.

- Practice standing knee extension exercises using a stretchy band. Take care that the band is not too narrow because this could press into the back of the knee and cause pain. Active contraction of knee extensors in this manner encourages relaxation in the opposing muscle group, the knee flexors.

- Practice knee extension in supine (figure 8.8b). This is a good starting point for clients with pain or balance issues, for whom the previous exercise may be too demanding. Simply rest comfortably and attempt to press the back of the knee into the bed, floor or treatment couch. Some people place a bolster or small rolled-up towel beneath the ankle to provide leverage.

- Actively stretch the soleus muscle.

- Avoid prolonged sitting where possible unless it is with the legs outstretched and knees extended. If in a seated job, take short breaks and stand every hour to stretch the back of the leg.

- Active soft tissue release can be useful in addressing specific regions of tension in posterior thigh tissues; it is a technique that enables the client to self-treat the knee in flexion.

- Temporarily avoid sports that might perpetuate a flexed knee posture, such as rowing and cycling.

|  |

Figure 8.8 Client techniques for genu flexum include letting gravity stretch the posterior tissues in (a) sitting or (b) active knee extension in a supine position.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Posture through the Habituation Lens

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Identification and Avoidance of Causal Habits

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture. Is your client performing some activity in her occupation, sport or recreational activity that contributes to the perpetuation of this posture? In some cases a client may know what these behaviours are. For example, she may have realized that wearing high heels shortens calf muscles because when she wears flat-heeled shoes, she has pain or a stretching sensation in those muscles. In many cases a client may be unaware that a behaviour is aggravating a particular posture. For example, regularly using the same hand to carry a heavy bag or always slinging a rucksack over the same shoulder results in more frequent contraction of levator scapulae muscles on that shoulder than of the other shoulder.

In a random selection of 100 participants, Guimond and Massrieh (2012) found a correlation between a person's demeanour and posture (see table 2.3), supporting the notion that the body shapes itself into various postures depending on the underlying mental and emotional state. Grouping particpants according to the four postures described by Kendall and McCreary (1983), they used a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator to determine characteristics of personality and discovered a relationship between posture type and two aspects of personality: extroversion and introversion. For example, they found that 96% of participants with 'perfect posture' were extrovert and only 4% were introvert, whereas the converse was true for participants with a kyphosis - lordosis posture, where only 17% were extrovert and 83% were introvert. This makes for slightly uncomfortable reading. If postural deviations are purely anatomical, manual correction of a joint or joints by either the client or a therapist is a good starting point in minimizing, eradicating or preventing an undesirable posture. There are enough variables to make this challenging. To add the variable of whether your client's personality might be correlated with posture raises many questions. For example, when attempting to correct the kyphosis - lordosis posture of your client, which Guimond and Massrieh found to correlate with the introverted personality type, would you be more successful if your client agreed to behave in a manner normally associated with extroversion? Can personality types be changed from introvert to extrovert, and would this affect posture?

There may, however, be a link between posture and emotion. Consider what happens to your own posture when you feel embarrassed, shy, ashamed, uncertain or withdrawn. Do you flex your spine, lower your head, flex your elbows, bring your hand to your mouth or jaw or hug yourself, making yourself physically smaller? Compare this to how your posture changes when you feel confident, certain and elated. Does your spine straighten, do you raise your head and do you pull back your shoulders? Changing how you feel affects muscle tone and overall posture, so the significance of the part played by your client in helping to correct his own posture - whether via physiological or emotional means - cannot be overemphasized.

Helping Your Client Identify, Eliminate or Reduce Causal Habits

- Use of pertinent questions during the subject stage of your assessment will help you identify factors that contribute to the posture that needs correction. A change in posture may be acute (e.g., an altered upper-limb posture after elbow fracture or altered neck or back posture associated with sudden spasm of a muscle), or it may be insidious (e.g., with progressive arthritis in the knee). Ask your client whether she regularly sustains a particular posture or regularly performs a repetitive action. These are likely to be contributing factors to imbalance in the body.

- Encourage your client to take an active part in the correction of posture.

- Encourage honest feedback. For example, did he do all of the exercises and stretches?

- Avoid overloading a client with too many stretches or exercises; instead, help him to focus on performing one or two correctly.

- Explain that, in some cases, correction can take weeks or months, depending on how long the body part has been out of alignment. In some cases correction may be readily attained, but what is important is sustained correction. Expecting gradual progress is probably a more realistic expectation than wanting immediate results.

- If you believe that some aspect of your client's work environment may be contributing to his posture, you may wish to refer him to the occupational health department of his organization, if there is one, or to an ergonomist. Factors affecting work-related musculoskeletal conditions are complex, and interventions require a tailored approach (Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2001). It seems reasonable that postural problems believed to have a work-related component are also likely to be complex and require an individualized approach.

- If your client has a job in which he remains seated at a computer, an ideal situation is for you to visit him and to assess how he is using the computer. Provide advice on basic computer setup and, if possible, follow the guidelines set forth in the appendix: Correct setup for display screen equipment to minimize postural stress in sitting. Give this advice to your client verbally and in printed form. Many sources of information are available for your client to refer to should he fall back into bad habits. Examples are Working With Display Screen Equipment (Health & Safety Executive 2013), How to Sit at a Computer (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2007), Perfect Posture (Chartered Society of Physiotherapists 2013) and Ergonomics Program: The Computer Workstation (National Institutes of Health 2014).

- Discourage reliance on your intervention in the long term. Hopefully, you will work with your client to help him correct a certain posture, and in doing so he will become aware of poor postural habits. Many professional sources are available for tips on postural correction, such as the American Chiropractic Association (2014). Your client may turn to these for gentle reminders on sitting, standing and sleeping postures in general.

Learn more about Postural Correction.

Find Out Who Benefits from Postural Correction

This is included as a technique because it is so important to the correction of posture. The physiological benefits of postural correction may be short lived if your client returns to those behaviours that were significant in bringing about such posture.

Who Might Benefit From Postural Correction?

The 30 postures described in Postural Correction are not specific to any one population, and many clients are likely to benefit from advice on avoiding or correcting postures that are likely to cause unwanted symptoms. The following list is not exhaustive but provides examples of the kinds of clients who may be susceptible to malalignment and for whom postural correction may be beneficial:

- Elderly people are more likely to present with genu valgum or genu varum when they are in the advanced stages of osteoarthritis. These postures can also be seen in people who have suffered knee injury or where injury or pathology affects the hips or ankles.

- The elderly are frequently observed to have kyphotic thoracic spines. So too are people who sit for prolonged periods or whose occupations involve repeated stooping.

- Many manual workers have asymmetric postures. For example, in the days when refuse bins were carried and emptied manually, refuse collectors portrayed lateral flexion of the spine as they repeatedly contracted muscles on one side in order to pick up and transport a dustbin. Whether such a working posture develops into true postural change is unknown but provides a good example of an activity that could lead to postural imbalance. Lateral flexion of the spine can also be observed in anyone who repeatedly carries a heavy bag on one side of the body. Vehicle-based camera crews filming sporting events have to look upwards to television screens for long periods, and at rest they may be observed to have hyperextension of the cervical spine. This is also common in linesmen employed to maintain overhead electrical cables, a job that necessitates climbing telegraph poles or using mobile elevated platforms whilst looking upwards. People with certain medical conditions are predisposed to malalignment. For example, hypermobile people lack stability in their joints and are likely to suffer increased cervical lordosis due to spondylolisthesis. Scoliosis is seen in 30% to 50% of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type; 23.7% have thoracic kyphosis and 43% to 55% have acquired flatfoot, and genu valgum often results from this foot posture (Tinkle 2008). In a study of 30 female teenagers with Down's syndrome, Dehghani and colleagues (2012) report the following percentages relating to specific postures: flatfoot (96%), genu valgum (83%), increased lumbar lordosis (63%), torticollis (lateral neck flexion) (60%), genu recurvatum (43%), kyphosis (10%), scoliosis (6%) and genu varum (3%).

- People who sustain injury to a joint may undergo a change in the posture of that joint, something that may be exacerbated through weight bearing. People who sustain injury during childhood sometimes develop marked asymmetrical postures in the lower limb and spine as they avoided bearing weight on the injured side. In some cases they never develop weight bearing equally through both lower limbs and show an unconscious preference for the uninjured side, despite having recovered many years previously from the initial injury.

- Non-symmetrical cervical postures may be observed in some people after whiplash injury.