- Home

- Tennis / Racquet Sports

- Strength Training and Conditioning

- Sports and Activities

- Complete Conditioning for Tennis

Complete Conditioning for Tennis

by Mark Kovacs, E. Paul Roetert, Todd S. Ellenbecker and United States Tennis Association (USTA)

Series: Complete Conditioning for Sports

304 Pages

Improve shot power, increase on-court speed and agility, and outlast the opposition with Complete Conditioning for Tennis, the most comprehensive tennis conditioning resource available!

The only strength and conditioning resource endorsed by the United States Tennis Association, Complete Conditioning for Tennis details how to maximize your training with exercises, drills, and programs that

• assess physical strengths and deficiencies,

• improve footwork and agility,

• increase speed and quickness,

• enhance stamina,

• increase flexibility,

• reduce recovery time, and

• prevent common injuries.

Throughout, you will have access to the same recommendations and routines used by today’s top professional players. From increasing the speed and power of your serve and groundstrokes to enhancing on-court agility and stamina, you will be ready to take the court with confidence and endure even the most grueling matches. Off the court, you’ll learn recovery techniques and preventive exercises for keeping shoulder and elbow injuries at bay.

Featuring more than 200 on- and off-court drills and exercises combined with exclusive online access to 56 video clips, Complete Conditioning for Tennis is an essential resource for players, coaches, instructors, and anyone serious about the sport.

Chapter 1. Meeting the Physical Demands of Tennis

Chapter 2. Muscles and Tennis Strokes

Chapter 3. Muscles and Tennis Movements

Chapter 4. High-Performance Fitness Testing

Chapter 5. Dynamic Warm-Up and Flexibility Training

Chapter 6. Speed, Agility, and Footwork Training

Chapter 7. Core Stability Training

Chapter 8. Strength Training

Chapter 9. Power Training

Chapter 10. Tennis-Specific Endurance Training

Chapter 11. Program Design and Periodization

Chapter 12. Solid Shoulder Stability

Chapter 13. Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation

Chapter 14. Nutrition and Hydration

Chapter 15. Recovery

Chapter 16. Age and Gender Considerations

The United States Tennis Association (USTA) is the national governing body for the sport of tennis and the recognized leader in promoting and developing the sport’s growth on every level in the United States, from local communities to the crown jewel of the professional game, the U.S. Open.

Established in 1881, the USTA is a progressive and diverse not-for-profit organization whose volunteers, professional staff, and financial resources support the singular mission.

The USTA is the largest tennis organization in the world, with 17 geographical sections, more than 700,000 individual members and more than 7,800 organizational members, thousands of volunteers, and a professional staff dedicated to growing the game.

In addition to the professional side of the sport, the USTA offers sanctioned league-play opportunities to players 18 years of age and older. Camps and other instructional opportunities are also provided to younger players around the country.

Mark Kovacs, PhD, FACSM, CTPS, MTPS, CSCS,*D, USPTA, PTR, is a performance physiologist, researcher, professor, author, speaker, and coach with an extensive background in training and researching elite athletes. He runs a consulting firm focused on optimizing human performance by the practical application of cutting-edge science. He is a consultant to the ATP, WTA, USTA, and NCAA. Dr. Kovacs also is the director of the Life Sport Science Institute and associate professor of sport health science at Life University. Heovacs has worked with hundreds of elite athletes and more than two dozen top professional tennis players, including John Isner, Robby Ginepri, Ryan Harrison, and Sloane Stephens.

He formerly directed the sport science, strength and conditioning, and coaching education departments for the United States Tennis Association and was the director of the Gatorade Sport Science Institute as well as an executive at Pepsico. He is coauthor of the book Tennis Anatomy (Human Kinetics, 2011).

Dr. Kovacs currently is the executive director of the International Tennis Performance Association (iTPA), the worldwide association for tennis-specific performance and injury prevention. He is a certified tennis performance specialist and a master tennis performance specialist through the iTPA. He is also a certified strength and conditioning specialist through the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) and both a USPTA and PTR certified tennis coach. Dr. Kovacs is a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine. In 2012, he was the youngest-ever recipient of the International Tennis Hall of Fame Educational Merit Award.

Kovacs was a collegiate All-American and NCAA doubles champion in tennis at Auburn University. After playing professionally, he performed tennis-specific research and earned a master’s degree in exercise science from Auburn University and a PhD in exercise physiology from the University of Alabama.

E. Paul Roetert, PhD, FACSM, is the chief executive officer of SHAPE America, the largest organization of professionals involved in school-based health, physical education, and physical activity. Founded in 1885, SHAPE America is committed to ensuring all children have the opportunity to lead healthy, physically active lives. He holds a PhD in biomechanics from the University of Connecticut and completed his bachelor

Major Movements

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot.

Split Step

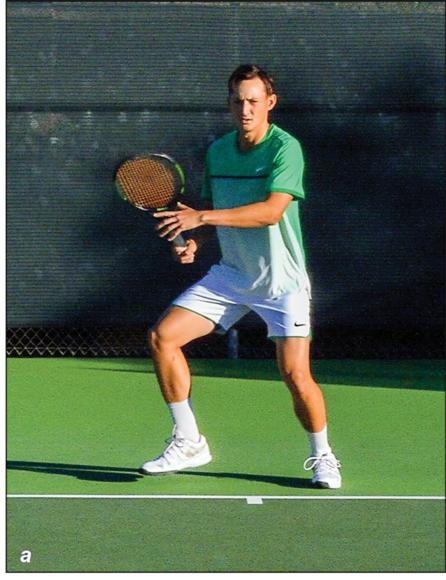

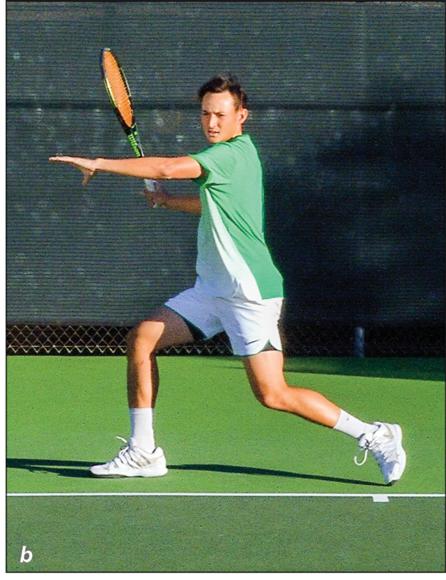

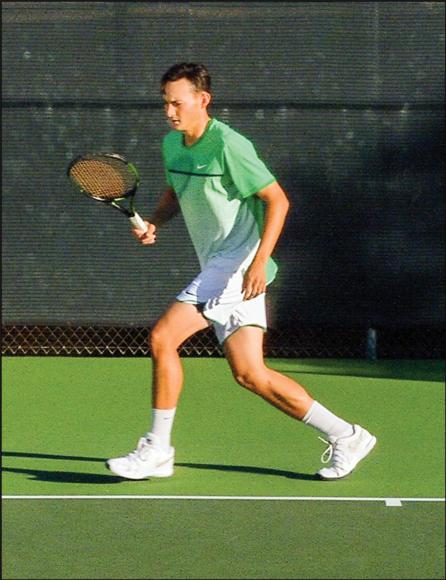

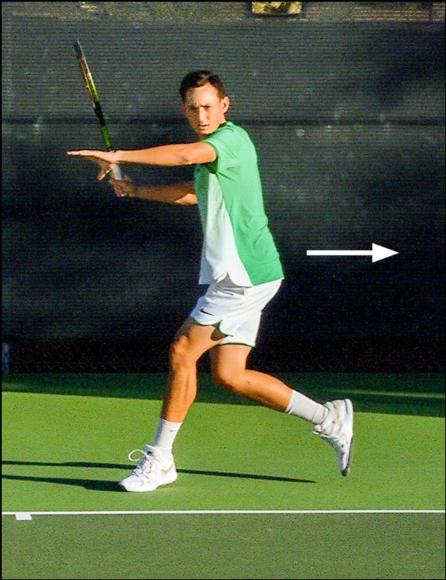

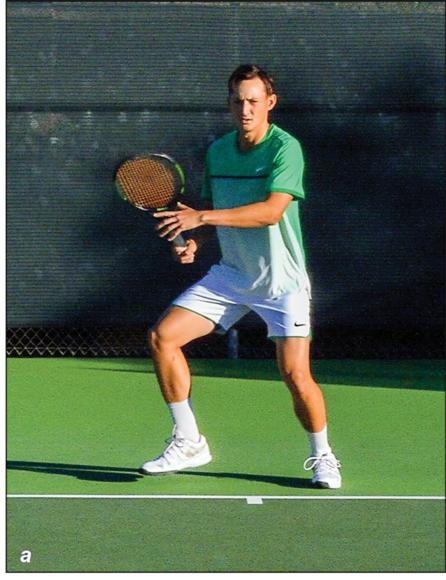

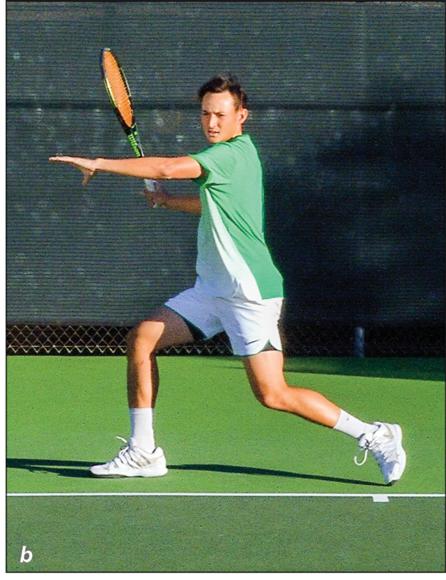

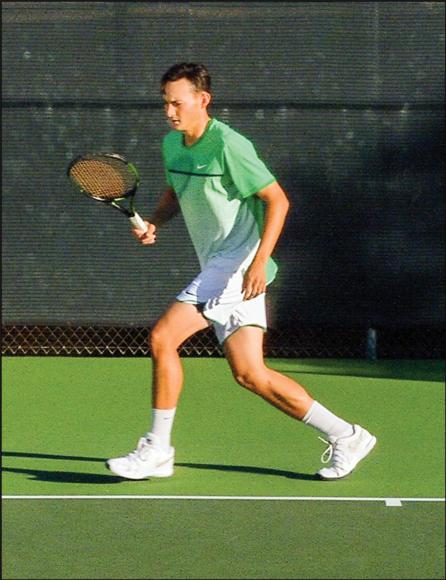

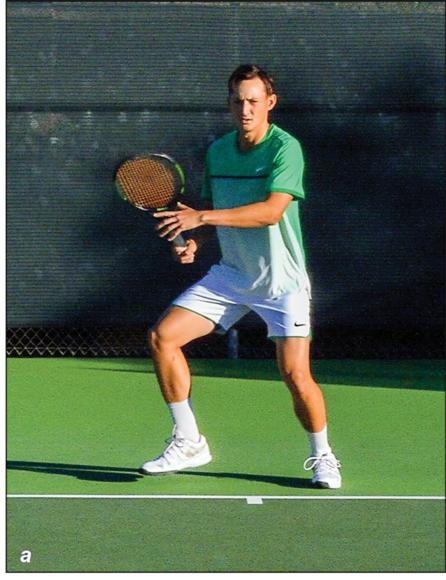

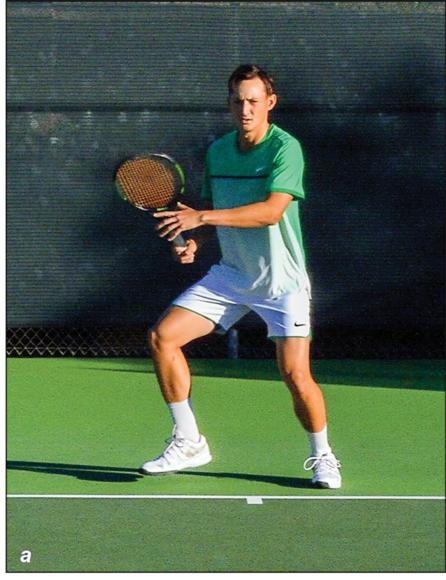

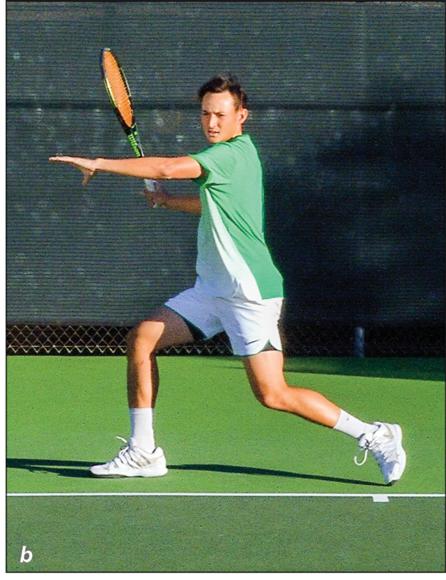

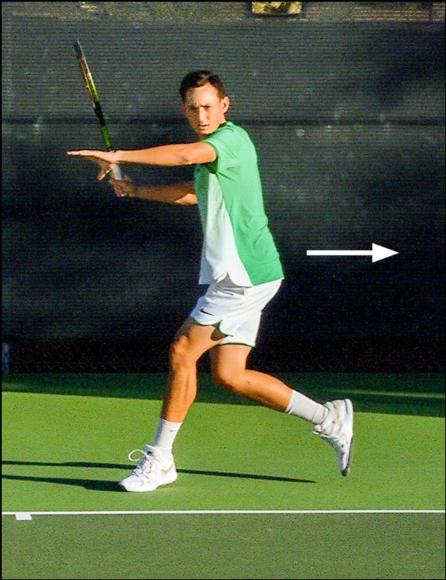

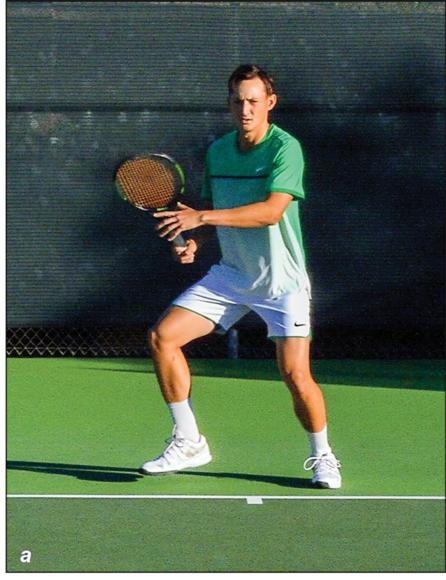

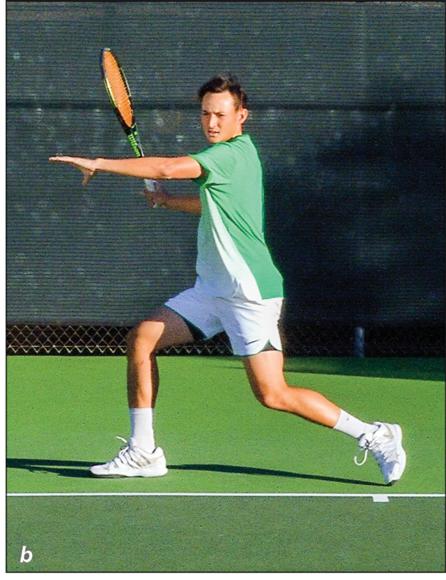

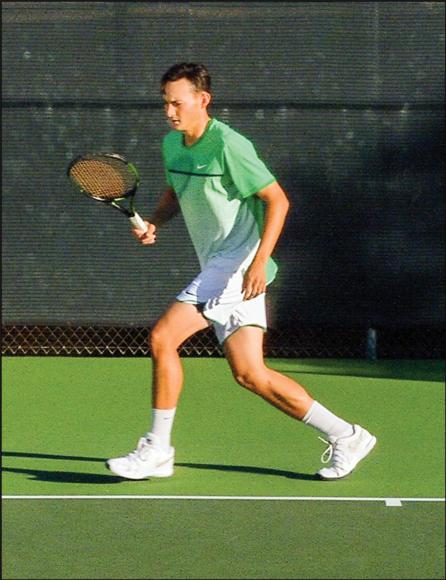

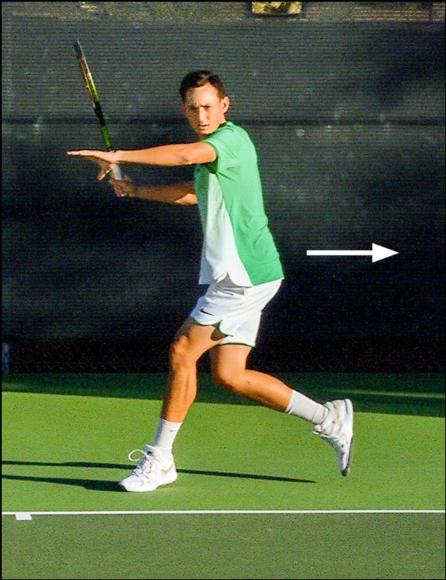

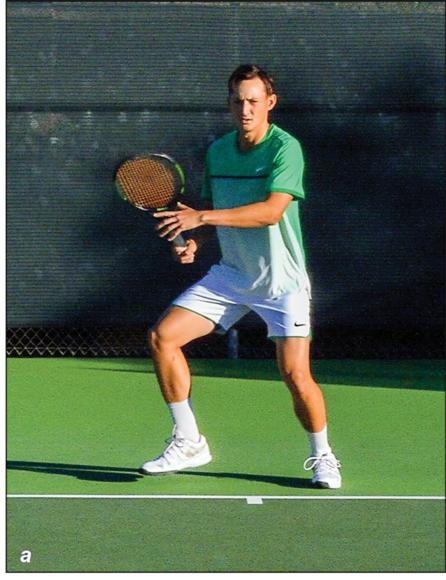

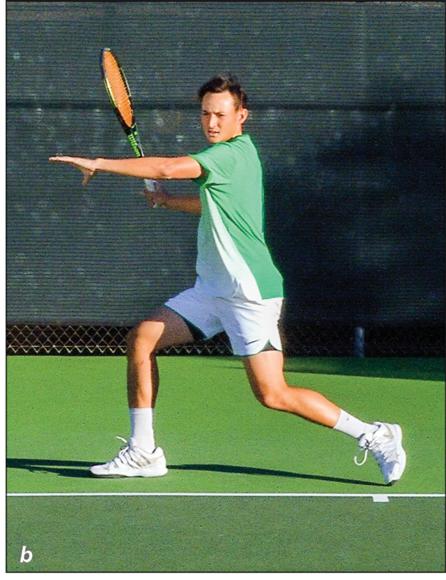

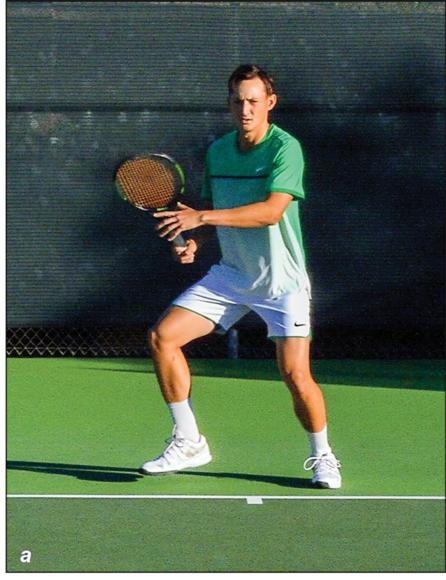

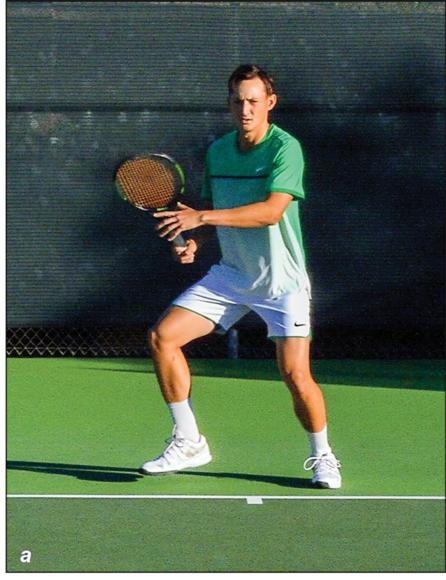

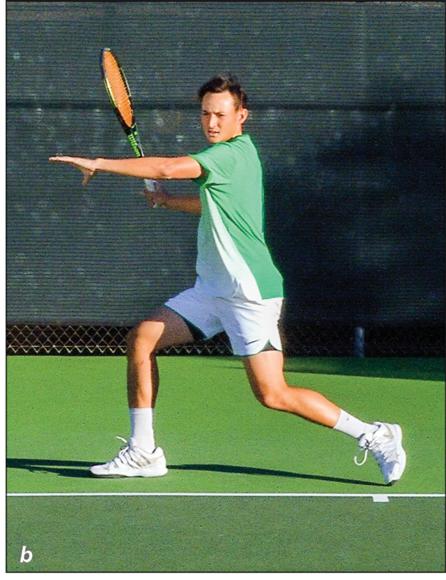

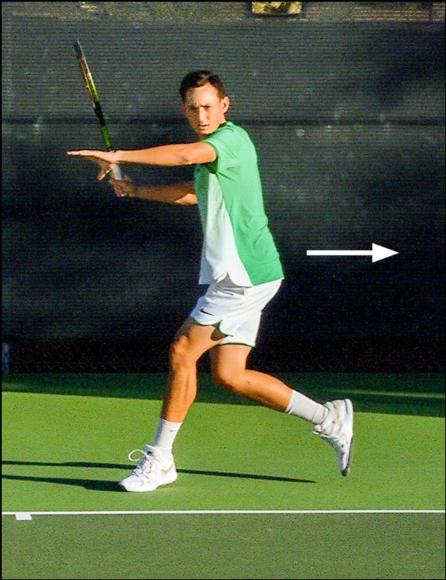

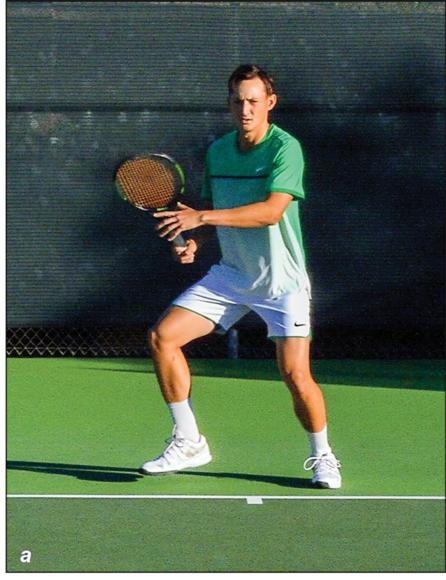

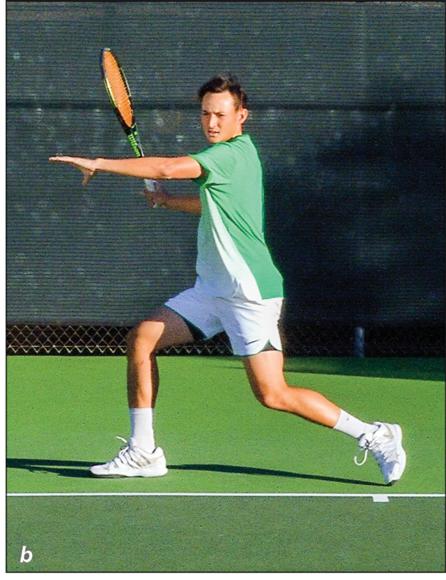

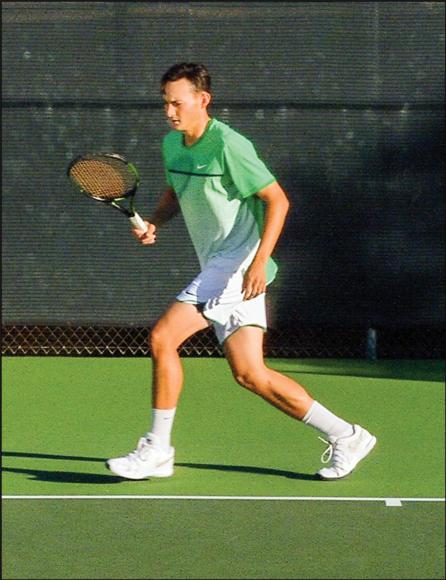

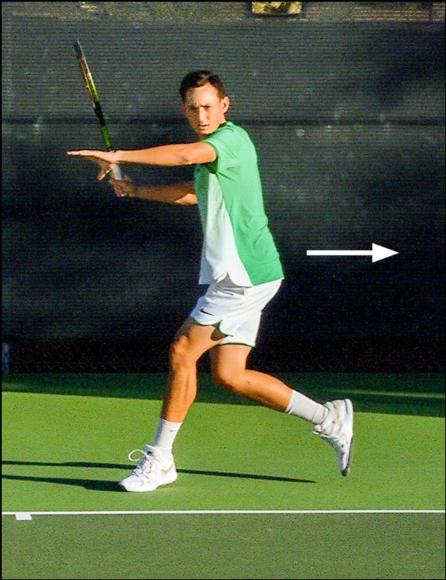

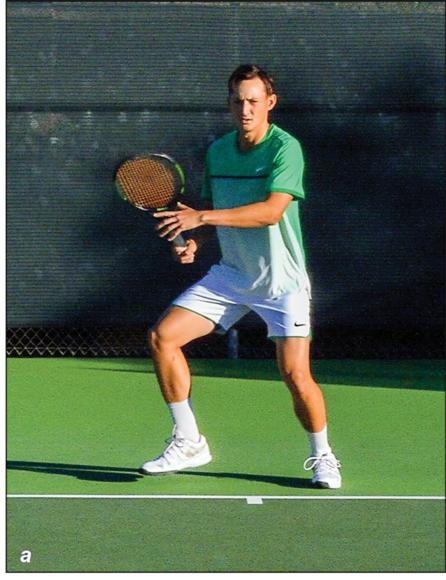

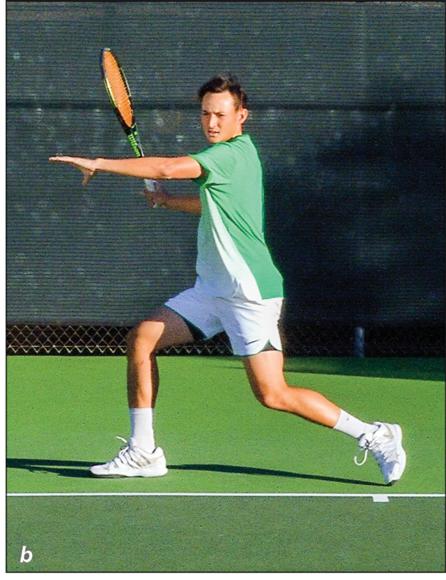

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot. For example, a right-handed player who is preparing to hit a forehand would land on the left foot first (figure 3.2a). Before the right foot touches the ground, the athlete subtly rotates the foot externally toward the intended movement toward the ball. For a right-handed player, this would result in the right foot landing and pointing outward (figure 3.2b). This movement pattern has been a natural evolution to improve the athletes' ability to react to the incoming ball and maximize their ratio of movement to time.

|  |

Split step landing: (a) loading on left foot; (b) right hip rotation.

Major Movements

Although thousands of movements occur in a single tennis match, a certain number of movements are common to the sport of tennis. Becoming proficient in these major movements will help you become a better mover on the tennis court and therefore a better overall player. Training for tennis requires that you repeat good quality movement patterns on a regular basis. Having a clear understanding of the correct movement patterns and how best to train to improve them will speed your improvement and make you more efficient on the court. Over time it can also reduce the chance of injury resulting from inefficient movements, poor loading patterns, and overuse as a result of inappropriate mechanics.

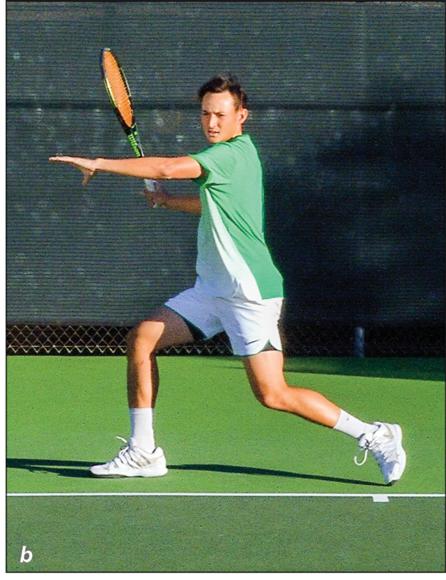

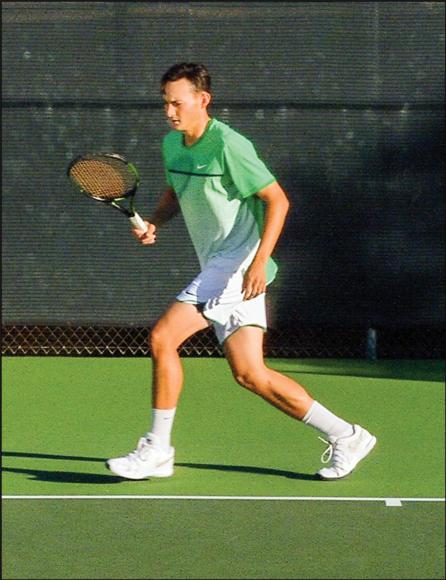

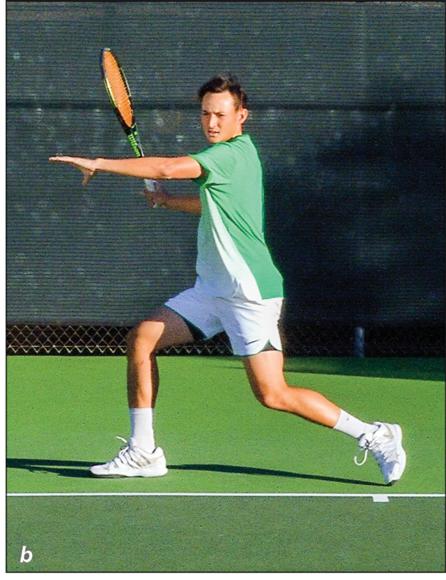

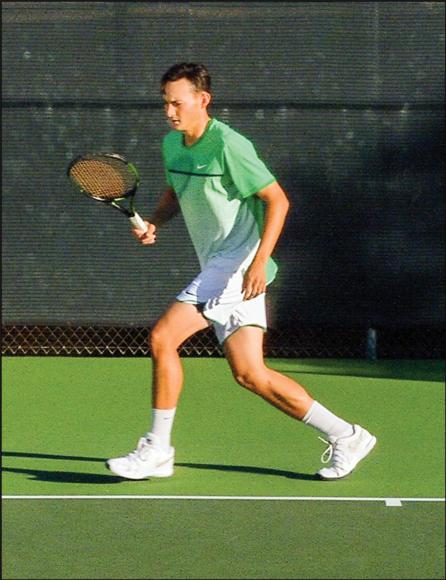

The jab step is defined as stepping first with the lead foot in the direction of the oncoming ball (figure 3.3).

Jab step.

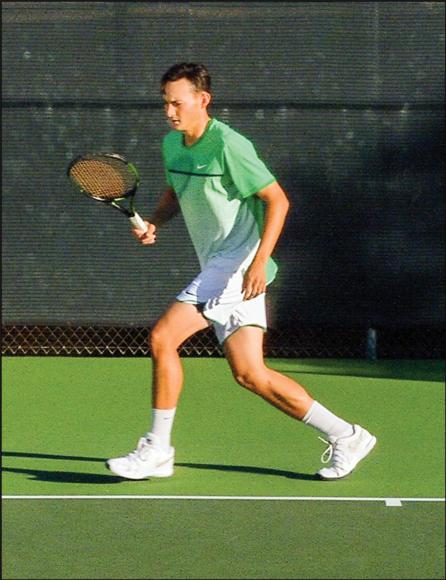

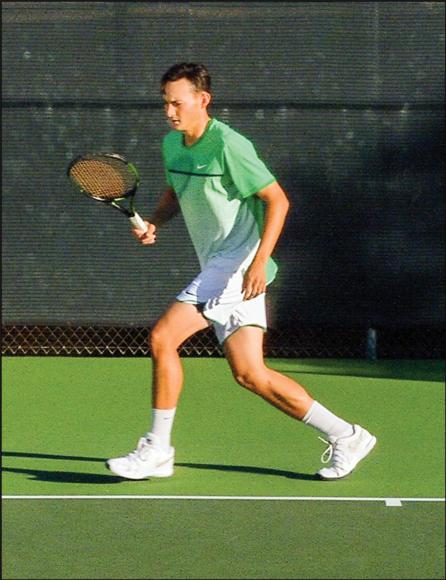

The pivot step involves pivoting on the lead foot while turning the hip toward the ball and making the first step toward the ball with the opposite leg (figure 3.4).

Pivot step.

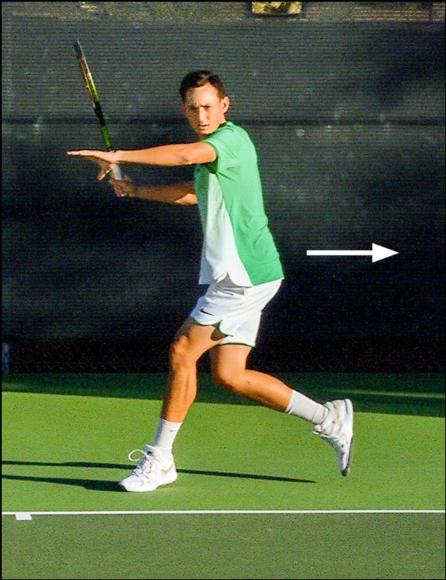

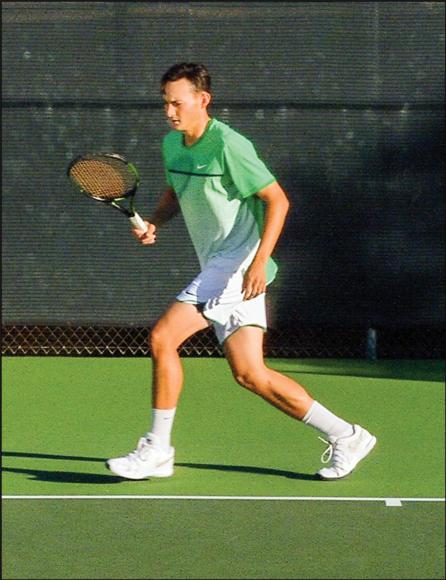

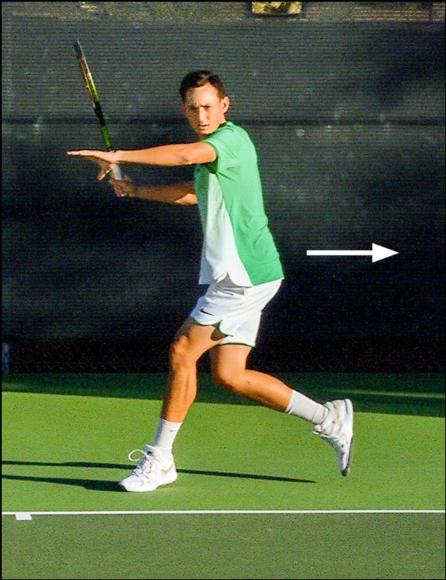

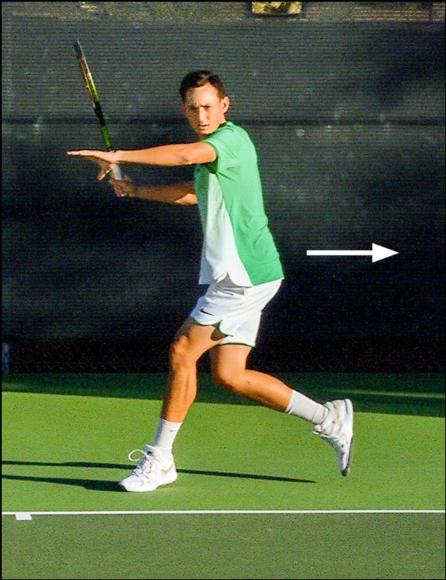

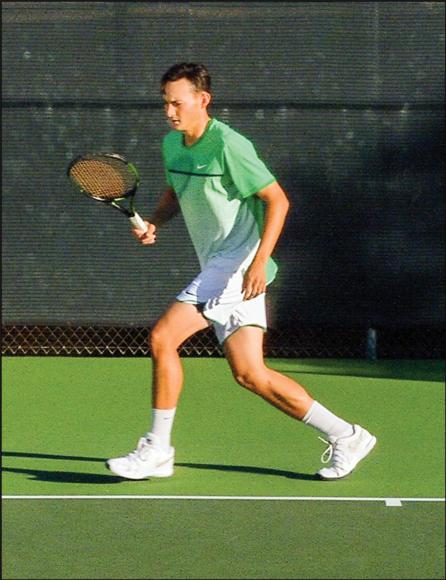

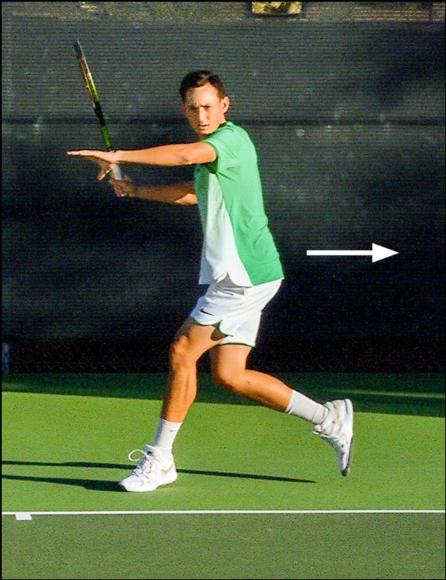

The drop step (i.e., run-around forehand) involves explosively turning the hips and dropping the outside leg behind the body to instigate the first movement when working on setting up for a run-around forehand stroke (figure 3.5).

Drop step.

Save

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Tennis and Energy Systems

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session.

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session. Aerobic fitness is also important for recovery following a strenuous baseline rally, bursts of movement, and maximal skills such as executing a serve-and-volley sequence or an overhead shot.

Anaerobic energy production is required for maximal activities during points. Testing (in the form of treadmill tests and intermittent endurance runs) on elite tennis players indicates high levels of aerobic fitness. Sprinting and agility tests indicate superior anaerobic power. These results explain a player's ability to maximally sprint from side to side during a baseline rally and then, after 20 to 25 seconds rest, do it again. Athletes with better aerobic fitness levels can clear the accumulated lactic acid from the working muscles more rapidly than players with less aerobic fitness. Likewise, athletes with greater aerobic power can run faster and jump higher because of greater energy stores in the trained muscle. However, tennis requires a balance, and the best tennis players have high levels of both anaerobic and aerobic fitness. Training needs to be structured appropriately to accurately match the demands of the sport of tennis and the player's game style.

Tennis Training for Anaerobic Power

Analysis of tennis matches generally determines that the average point lasts less than 10 seconds; some points can last 20 to 30 seconds. Most players' average rest time is 18 to 20 seconds, with a maximum allowable rest time between points being 20 or 25 seconds, depending on competition rules. The ratio of work time to rest time is termed the work - rest cycle. A 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle is most representative of the physiological activity pattern experienced during tennis. This means that for every 1 second of work, you will have 2 to 5 seconds of rest. In practical terms, a 10-second point would result in a 20- to 50-second rest. The reason that some matches involve a work - ratio of 1:5 is that it accounts for the time during change-overs (90 seconds), and some matches have shorter work periods than 10 seconds as well. Therefore, to appropriately cover all environments seen during tennis matches it is appropriate to cycle your tennis-specific training using a 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest ratio. In addition to the work - rest cycle concept, the term specificity is often applied. Specificity involves training the athlete in a manner most similar to the actual demands of the sport. It means using movement patterns, distances, and times similar to tennis play. For example, running 5 miles builds aerobic conditioning, but it has very little specificity to tennis play. Performing tennis-specific endurance training involves a number of short-duration, multidirectional movements at high intensity with the work - rest ratios mentioned earlier. This training is more specific to tennis than running at a slow pace for 5 miles.

Anaerobic training techniques in tennis use both concepts of work - rest cycle and specificity. Drills and activities used to improve anaerobic power follow the 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle and include relatively short-duration, multidirectional movement patterns. The characteristics of tennis play that can be incorporated into tennis-specific training include the following:

- A tennis point usually includes four or five directional changes.

- Most tennis points last fewer than 10 seconds.

- Tennis players always carry their rackets during points.

- Players seldom run more than 30 feet (9 m) in one direction during a point.

- Movement patterns contain acceleration and controlled deceleration.

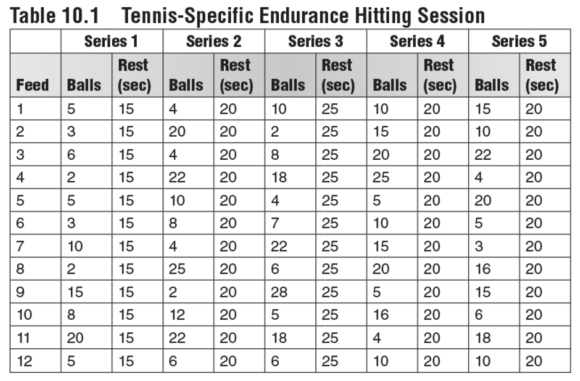

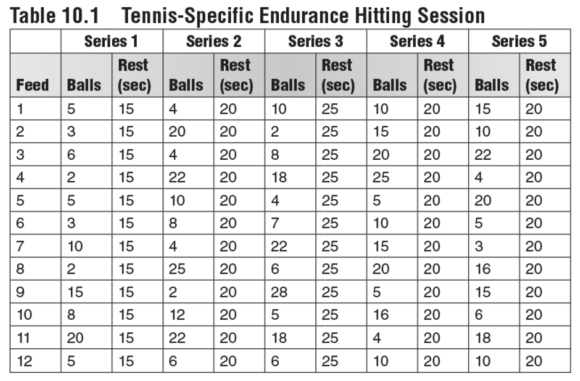

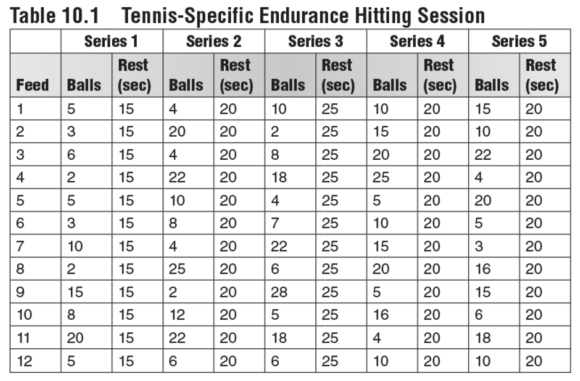

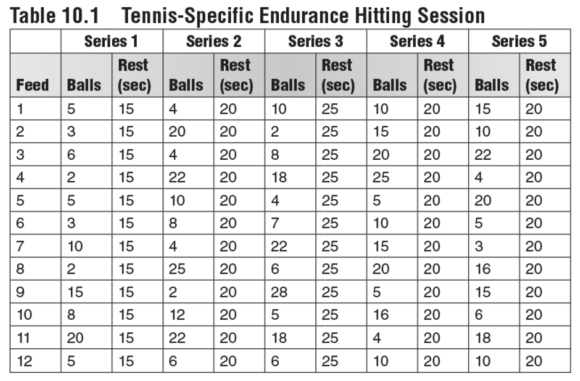

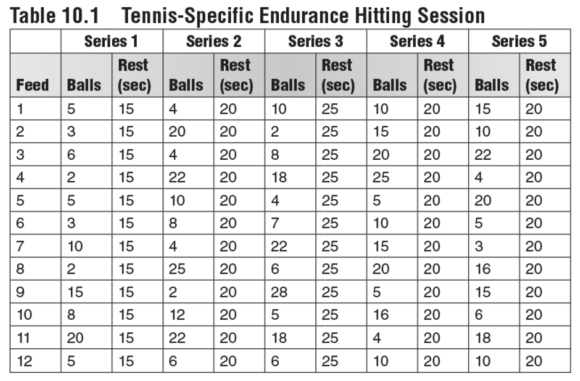

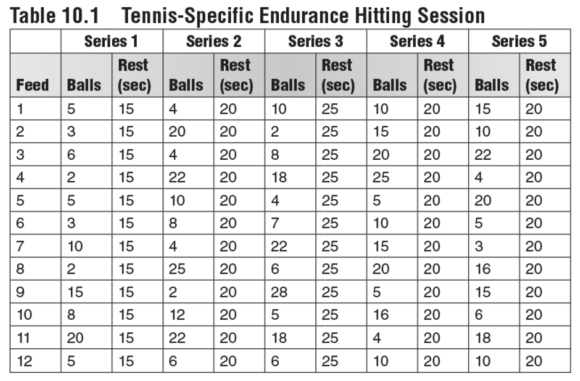

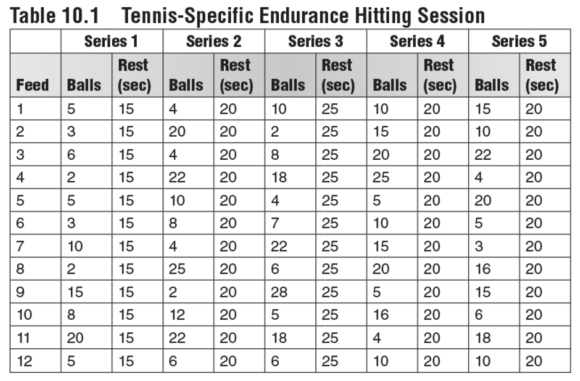

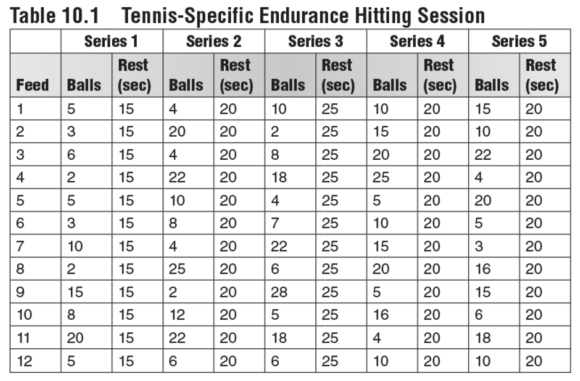

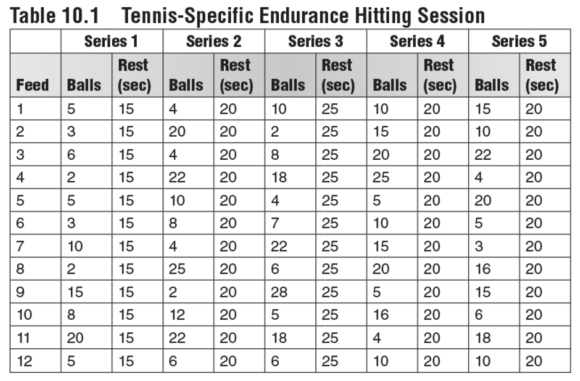

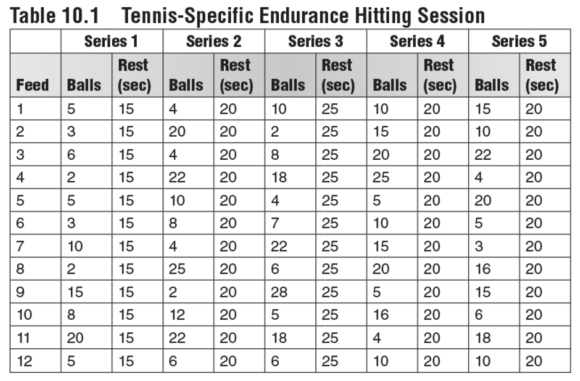

These characteristics can be incorporated into a hitting session with a ball machine or coach (table 10.1). The player takes a 90-second sit-down break between each series. During the 90-second break, the feeder must pick up the balls and prepare for the next series. Heart rate can be recorded at the start and end of each 90-second break between series. The goal would be to reduce heart rate significantly during that time period. Also, you could set up targets to hit within. If so, record the number of balls hit outside the designated target areas. The goal is to keep errors to a minimum during all sequences.

Tennis-specific drills to improve on-court movement and footwork as well as anaerobic power are included in chapters 5 and 6. Any exercise that includes a relatively short period of maximal-intensity work followed by a period of recovery that is approximately two times longer than the period of work stresses the anaerobic energy system. General anaerobic training drills for tennis include classic on-court movement drills such as cross cones (chapter 6) and line drills such as the sideways shuffle, alley hop, and spider run (chapter 6). To make these general anaerobic training drills more specific to tennis, perform them with a tennis racket in hand as you would do when you play tennis.

Another beneficial training exercise is also sometimes used as a fitness test for tennis. The MK drill (described as a test in chapter 4) is one of the most useful training exercises to develop tennis-specific endurance; it follows ratios of work to rest for tennis and covers distances seen on the tennis court; you sprint 36 feet (10.97 m) in one direction before turning. The MK drill is a good drill that takes 15 to 20 minutes and can be performed on the tennis court once or twice per week as part of a structured periodized training program to help improve tennis-specific endurance.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Shoulder Injuries in Tennis

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched.

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched. When this happens over and over again, it can injure the tendon. The labrum or cartilage in the shoulder socket also can become injured (torn) in overhead athletes, especially those with very loose shoulders and poor rotator cuff strength and shoulder stability. Many of the shoulder injuries seen in tennis can be prevented with a proper stretching and strengthening program.

Stretches to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

The two most important shoulder stretches for tennis players are the cross-arm stretch and the sleeper stretch. Research shows that using these stretches as part of a regular program will improve the range of motion of internal rotation.

Preventive Shoulder Stretches

As with any stretch, perform them after tennis play and complete 2 or 3 repetitions of each stretch, holding each for 20 to 30 seconds. This will improve or maintain flexibility in the shoulder.

Posterior Shoulder Stretch (Cross-Arm Stretch)

Focus

Improve flexibility of the muscles in the back of the shoulder and back of the shoulder joint capsule.

Procedure

- Stand next to a doorway or fence. Raise your racket arm to shoulder level. Brace the side of your shoulder and shoulder blade against the wall or fence to keep the shoulder blade from sliding forward when you begin the stretch.

- Using the other hand, grab the outside of the elbow of your racket hand and pull your arm across your chest (figure 12.3). You should feel the stretch in the back of your shoulder.

- Hold the position, then switch sides.

Note

If you feel a pinching sensation in the front of your shoulder, discontinue this stretch and use the sleeper stretch to accomplish a similar stretch for this portion of the shoulder.

Cross-arm stretch.

Strengthening Exercises to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

Increasing muscular endurance and building a base level of strength in the rotator cuff and upper back should be the goals of any shoulder-strengthening program. The following exercises can be used to strengthen the back, or posterior part, of the rotator cuff. Perform each of these exercises slowly and with proper form.

Begin by performing these exercises using three sets of 15 to 20 repetitions. However, you must maintain proper technique when performing these exercises, even on the 20th repetition in the third set. Do not hesitate to do fewer repetitions or sets if you cannot maintain proper technique; it is better to do fewer repetitions correctly than more repetitions incorrectly. When done correctly, these exercises should not produce pain, just a feeling of burning around the shoulder. These exercises should be done after tennis play, to prevent fatiguing the shoulder prior to tennis play. The exercises are most important to be done with the dominant (tennis playing) shoulder.

Shoulder Strengthening Exercises With Weights

Most young players need to use only a 1-pound (0.45-kg) weight to start strengthening the shoulder muscles. Remember, these muscles are small, and tennis players do not need to lift a lot of weight to strengthen them appropriately. In fact, if using too much weight, players will substitute and use muscles other than the rotator cuff to perform the exercise.

Older, more experienced players will experience significant muscular fatigue doing these exercises using a 1.5- or 2-pound (0.7- or 0.9-kg) weight if the exercises are done correctly. Control the weight as you lift it (while muscles are shortening) and when you lower it (while muscles are lengthening), because this control prepares the muscle for the specific performance demands encountered during tennis play. As you get stronger, increase the weight in 1/2-pound (0.2-kg) increments, but only after you can do all three sets without significant fatigue and without using other parts of your body to compensate.

Sidelying External Rotation

Focus

Strengthen the external rotator muscles of the shoulder.

Procedure

- Lie on one side with your working arm (top arm) at your side and a small pillow between your arm and body. Hold a small dumbbell in the hand of your working arm.

- Keeping the elbow of your working arm bent and fixed to your side, raise your arm into external rotation until it is just short of pointing straight up (figure 12.5).

- Slowly lower the arm to the starting position.

- Repeat the exercise on the other side.

Sidelying external rotation.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Flexibility Training

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following: Stretching may not feel particularly good. The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following:

- Stretching may not feel particularly good.

- The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

- Most players have been given no specific individualized guidelines as to how, why, what, and when to stretch.

- Many coaches emphasize stretching less than the other components of conditioning

The term flexibility can be defined as the degree of extensibility of the soft tissue structures surrounding the joint, such as muscles, tendons, and connective tissue. Two main types of flexibility exist. Static flexibility describes the measured range of motion about a joint or series of joints, and dynamic flexibility refers to the active motion about a joint or series of joints. Dynamic flexibility is limited by the resistance to motion of the joint structures, the ability of the soft connective tissues to deform, and neuromuscular components.

Factors influencing flexibility include heredity, neuromuscular components, and tissue temperature. In regard to heredity, body design determines overall flexibility potential. While most people tend to be relatively inflexible, a small few are hyperflexible. Aspects of heredity and body design that affect flexibility potential include the shape and orientation of joint surfaces, as well as the physiological characteristics of the joint capsule, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. In addition, because of the nature of the movements performed while playing tennis and from the repetitive nature of these stresses, some areas of the tennis player's body can be very tight and inflexible. These areas include the hamstrings, low back, and muscles in the back of the shoulder. At the same time, other areas in the tennis player's body may be overly flexible, such as the front of the shoulder (external rotation). These adaptations are the result of many years of playing tennis.

Sleeper Stretch

Focus

Improve flexibility of the shoulder rotators and upper-back (scapular) muscles.

Procedure

- Lie on your dominant shoulder as you would when sleeping on your side.

- Place your dominant arm directly in front of you at a 90-degree angle, keeping the elbow bent 90 degrees as well.

- Using your other arm, push your hand down toward your feet, internally rotating your shoulder (figure 5.15).

- Hold the position for 15 to 30 seconds, then repeat the stretch on the other side.

Note

You can make this stretch even more intense by placing your chin against the front of the shoulder you are lying on, pressing it down even more to provide greater stabilization to increase the stretch.

Sleeper stretch.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Major Movements

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot.

Split Step

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot. For example, a right-handed player who is preparing to hit a forehand would land on the left foot first (figure 3.2a). Before the right foot touches the ground, the athlete subtly rotates the foot externally toward the intended movement toward the ball. For a right-handed player, this would result in the right foot landing and pointing outward (figure 3.2b). This movement pattern has been a natural evolution to improve the athletes' ability to react to the incoming ball and maximize their ratio of movement to time.

|  |

Split step landing: (a) loading on left foot; (b) right hip rotation.

Major Movements

Although thousands of movements occur in a single tennis match, a certain number of movements are common to the sport of tennis. Becoming proficient in these major movements will help you become a better mover on the tennis court and therefore a better overall player. Training for tennis requires that you repeat good quality movement patterns on a regular basis. Having a clear understanding of the correct movement patterns and how best to train to improve them will speed your improvement and make you more efficient on the court. Over time it can also reduce the chance of injury resulting from inefficient movements, poor loading patterns, and overuse as a result of inappropriate mechanics.

The jab step is defined as stepping first with the lead foot in the direction of the oncoming ball (figure 3.3).

Jab step.

The pivot step involves pivoting on the lead foot while turning the hip toward the ball and making the first step toward the ball with the opposite leg (figure 3.4).

Pivot step.

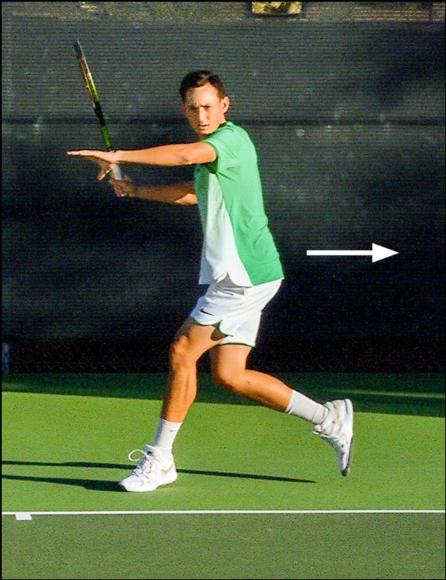

The drop step (i.e., run-around forehand) involves explosively turning the hips and dropping the outside leg behind the body to instigate the first movement when working on setting up for a run-around forehand stroke (figure 3.5).

Drop step.

Save

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Tennis and Energy Systems

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session.

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session. Aerobic fitness is also important for recovery following a strenuous baseline rally, bursts of movement, and maximal skills such as executing a serve-and-volley sequence or an overhead shot.

Anaerobic energy production is required for maximal activities during points. Testing (in the form of treadmill tests and intermittent endurance runs) on elite tennis players indicates high levels of aerobic fitness. Sprinting and agility tests indicate superior anaerobic power. These results explain a player's ability to maximally sprint from side to side during a baseline rally and then, after 20 to 25 seconds rest, do it again. Athletes with better aerobic fitness levels can clear the accumulated lactic acid from the working muscles more rapidly than players with less aerobic fitness. Likewise, athletes with greater aerobic power can run faster and jump higher because of greater energy stores in the trained muscle. However, tennis requires a balance, and the best tennis players have high levels of both anaerobic and aerobic fitness. Training needs to be structured appropriately to accurately match the demands of the sport of tennis and the player's game style.

Tennis Training for Anaerobic Power

Analysis of tennis matches generally determines that the average point lasts less than 10 seconds; some points can last 20 to 30 seconds. Most players' average rest time is 18 to 20 seconds, with a maximum allowable rest time between points being 20 or 25 seconds, depending on competition rules. The ratio of work time to rest time is termed the work - rest cycle. A 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle is most representative of the physiological activity pattern experienced during tennis. This means that for every 1 second of work, you will have 2 to 5 seconds of rest. In practical terms, a 10-second point would result in a 20- to 50-second rest. The reason that some matches involve a work - ratio of 1:5 is that it accounts for the time during change-overs (90 seconds), and some matches have shorter work periods than 10 seconds as well. Therefore, to appropriately cover all environments seen during tennis matches it is appropriate to cycle your tennis-specific training using a 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest ratio. In addition to the work - rest cycle concept, the term specificity is often applied. Specificity involves training the athlete in a manner most similar to the actual demands of the sport. It means using movement patterns, distances, and times similar to tennis play. For example, running 5 miles builds aerobic conditioning, but it has very little specificity to tennis play. Performing tennis-specific endurance training involves a number of short-duration, multidirectional movements at high intensity with the work - rest ratios mentioned earlier. This training is more specific to tennis than running at a slow pace for 5 miles.

Anaerobic training techniques in tennis use both concepts of work - rest cycle and specificity. Drills and activities used to improve anaerobic power follow the 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle and include relatively short-duration, multidirectional movement patterns. The characteristics of tennis play that can be incorporated into tennis-specific training include the following:

- A tennis point usually includes four or five directional changes.

- Most tennis points last fewer than 10 seconds.

- Tennis players always carry their rackets during points.

- Players seldom run more than 30 feet (9 m) in one direction during a point.

- Movement patterns contain acceleration and controlled deceleration.

These characteristics can be incorporated into a hitting session with a ball machine or coach (table 10.1). The player takes a 90-second sit-down break between each series. During the 90-second break, the feeder must pick up the balls and prepare for the next series. Heart rate can be recorded at the start and end of each 90-second break between series. The goal would be to reduce heart rate significantly during that time period. Also, you could set up targets to hit within. If so, record the number of balls hit outside the designated target areas. The goal is to keep errors to a minimum during all sequences.

Tennis-specific drills to improve on-court movement and footwork as well as anaerobic power are included in chapters 5 and 6. Any exercise that includes a relatively short period of maximal-intensity work followed by a period of recovery that is approximately two times longer than the period of work stresses the anaerobic energy system. General anaerobic training drills for tennis include classic on-court movement drills such as cross cones (chapter 6) and line drills such as the sideways shuffle, alley hop, and spider run (chapter 6). To make these general anaerobic training drills more specific to tennis, perform them with a tennis racket in hand as you would do when you play tennis.

Another beneficial training exercise is also sometimes used as a fitness test for tennis. The MK drill (described as a test in chapter 4) is one of the most useful training exercises to develop tennis-specific endurance; it follows ratios of work to rest for tennis and covers distances seen on the tennis court; you sprint 36 feet (10.97 m) in one direction before turning. The MK drill is a good drill that takes 15 to 20 minutes and can be performed on the tennis court once or twice per week as part of a structured periodized training program to help improve tennis-specific endurance.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Shoulder Injuries in Tennis

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched.

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched. When this happens over and over again, it can injure the tendon. The labrum or cartilage in the shoulder socket also can become injured (torn) in overhead athletes, especially those with very loose shoulders and poor rotator cuff strength and shoulder stability. Many of the shoulder injuries seen in tennis can be prevented with a proper stretching and strengthening program.

Stretches to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

The two most important shoulder stretches for tennis players are the cross-arm stretch and the sleeper stretch. Research shows that using these stretches as part of a regular program will improve the range of motion of internal rotation.

Preventive Shoulder Stretches

As with any stretch, perform them after tennis play and complete 2 or 3 repetitions of each stretch, holding each for 20 to 30 seconds. This will improve or maintain flexibility in the shoulder.

Posterior Shoulder Stretch (Cross-Arm Stretch)

Focus

Improve flexibility of the muscles in the back of the shoulder and back of the shoulder joint capsule.

Procedure

- Stand next to a doorway or fence. Raise your racket arm to shoulder level. Brace the side of your shoulder and shoulder blade against the wall or fence to keep the shoulder blade from sliding forward when you begin the stretch.

- Using the other hand, grab the outside of the elbow of your racket hand and pull your arm across your chest (figure 12.3). You should feel the stretch in the back of your shoulder.

- Hold the position, then switch sides.

Note

If you feel a pinching sensation in the front of your shoulder, discontinue this stretch and use the sleeper stretch to accomplish a similar stretch for this portion of the shoulder.

Cross-arm stretch.

Strengthening Exercises to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

Increasing muscular endurance and building a base level of strength in the rotator cuff and upper back should be the goals of any shoulder-strengthening program. The following exercises can be used to strengthen the back, or posterior part, of the rotator cuff. Perform each of these exercises slowly and with proper form.

Begin by performing these exercises using three sets of 15 to 20 repetitions. However, you must maintain proper technique when performing these exercises, even on the 20th repetition in the third set. Do not hesitate to do fewer repetitions or sets if you cannot maintain proper technique; it is better to do fewer repetitions correctly than more repetitions incorrectly. When done correctly, these exercises should not produce pain, just a feeling of burning around the shoulder. These exercises should be done after tennis play, to prevent fatiguing the shoulder prior to tennis play. The exercises are most important to be done with the dominant (tennis playing) shoulder.

Shoulder Strengthening Exercises With Weights

Most young players need to use only a 1-pound (0.45-kg) weight to start strengthening the shoulder muscles. Remember, these muscles are small, and tennis players do not need to lift a lot of weight to strengthen them appropriately. In fact, if using too much weight, players will substitute and use muscles other than the rotator cuff to perform the exercise.

Older, more experienced players will experience significant muscular fatigue doing these exercises using a 1.5- or 2-pound (0.7- or 0.9-kg) weight if the exercises are done correctly. Control the weight as you lift it (while muscles are shortening) and when you lower it (while muscles are lengthening), because this control prepares the muscle for the specific performance demands encountered during tennis play. As you get stronger, increase the weight in 1/2-pound (0.2-kg) increments, but only after you can do all three sets without significant fatigue and without using other parts of your body to compensate.

Sidelying External Rotation

Focus

Strengthen the external rotator muscles of the shoulder.

Procedure

- Lie on one side with your working arm (top arm) at your side and a small pillow between your arm and body. Hold a small dumbbell in the hand of your working arm.

- Keeping the elbow of your working arm bent and fixed to your side, raise your arm into external rotation until it is just short of pointing straight up (figure 12.5).

- Slowly lower the arm to the starting position.

- Repeat the exercise on the other side.

Sidelying external rotation.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Flexibility Training

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following: Stretching may not feel particularly good. The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following:

- Stretching may not feel particularly good.

- The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

- Most players have been given no specific individualized guidelines as to how, why, what, and when to stretch.

- Many coaches emphasize stretching less than the other components of conditioning

The term flexibility can be defined as the degree of extensibility of the soft tissue structures surrounding the joint, such as muscles, tendons, and connective tissue. Two main types of flexibility exist. Static flexibility describes the measured range of motion about a joint or series of joints, and dynamic flexibility refers to the active motion about a joint or series of joints. Dynamic flexibility is limited by the resistance to motion of the joint structures, the ability of the soft connective tissues to deform, and neuromuscular components.

Factors influencing flexibility include heredity, neuromuscular components, and tissue temperature. In regard to heredity, body design determines overall flexibility potential. While most people tend to be relatively inflexible, a small few are hyperflexible. Aspects of heredity and body design that affect flexibility potential include the shape and orientation of joint surfaces, as well as the physiological characteristics of the joint capsule, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. In addition, because of the nature of the movements performed while playing tennis and from the repetitive nature of these stresses, some areas of the tennis player's body can be very tight and inflexible. These areas include the hamstrings, low back, and muscles in the back of the shoulder. At the same time, other areas in the tennis player's body may be overly flexible, such as the front of the shoulder (external rotation). These adaptations are the result of many years of playing tennis.

Sleeper Stretch

Focus

Improve flexibility of the shoulder rotators and upper-back (scapular) muscles.

Procedure

- Lie on your dominant shoulder as you would when sleeping on your side.

- Place your dominant arm directly in front of you at a 90-degree angle, keeping the elbow bent 90 degrees as well.

- Using your other arm, push your hand down toward your feet, internally rotating your shoulder (figure 5.15).

- Hold the position for 15 to 30 seconds, then repeat the stretch on the other side.

Note

You can make this stretch even more intense by placing your chin against the front of the shoulder you are lying on, pressing it down even more to provide greater stabilization to increase the stretch.

Sleeper stretch.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Major Movements

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot.

Split Step

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot. For example, a right-handed player who is preparing to hit a forehand would land on the left foot first (figure 3.2a). Before the right foot touches the ground, the athlete subtly rotates the foot externally toward the intended movement toward the ball. For a right-handed player, this would result in the right foot landing and pointing outward (figure 3.2b). This movement pattern has been a natural evolution to improve the athletes' ability to react to the incoming ball and maximize their ratio of movement to time.

|  |

Split step landing: (a) loading on left foot; (b) right hip rotation.

Major Movements

Although thousands of movements occur in a single tennis match, a certain number of movements are common to the sport of tennis. Becoming proficient in these major movements will help you become a better mover on the tennis court and therefore a better overall player. Training for tennis requires that you repeat good quality movement patterns on a regular basis. Having a clear understanding of the correct movement patterns and how best to train to improve them will speed your improvement and make you more efficient on the court. Over time it can also reduce the chance of injury resulting from inefficient movements, poor loading patterns, and overuse as a result of inappropriate mechanics.

The jab step is defined as stepping first with the lead foot in the direction of the oncoming ball (figure 3.3).

Jab step.

The pivot step involves pivoting on the lead foot while turning the hip toward the ball and making the first step toward the ball with the opposite leg (figure 3.4).

Pivot step.

The drop step (i.e., run-around forehand) involves explosively turning the hips and dropping the outside leg behind the body to instigate the first movement when working on setting up for a run-around forehand stroke (figure 3.5).

Drop step.

Save

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Tennis and Energy Systems

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session.

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session. Aerobic fitness is also important for recovery following a strenuous baseline rally, bursts of movement, and maximal skills such as executing a serve-and-volley sequence or an overhead shot.

Anaerobic energy production is required for maximal activities during points. Testing (in the form of treadmill tests and intermittent endurance runs) on elite tennis players indicates high levels of aerobic fitness. Sprinting and agility tests indicate superior anaerobic power. These results explain a player's ability to maximally sprint from side to side during a baseline rally and then, after 20 to 25 seconds rest, do it again. Athletes with better aerobic fitness levels can clear the accumulated lactic acid from the working muscles more rapidly than players with less aerobic fitness. Likewise, athletes with greater aerobic power can run faster and jump higher because of greater energy stores in the trained muscle. However, tennis requires a balance, and the best tennis players have high levels of both anaerobic and aerobic fitness. Training needs to be structured appropriately to accurately match the demands of the sport of tennis and the player's game style.

Tennis Training for Anaerobic Power

Analysis of tennis matches generally determines that the average point lasts less than 10 seconds; some points can last 20 to 30 seconds. Most players' average rest time is 18 to 20 seconds, with a maximum allowable rest time between points being 20 or 25 seconds, depending on competition rules. The ratio of work time to rest time is termed the work - rest cycle. A 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle is most representative of the physiological activity pattern experienced during tennis. This means that for every 1 second of work, you will have 2 to 5 seconds of rest. In practical terms, a 10-second point would result in a 20- to 50-second rest. The reason that some matches involve a work - ratio of 1:5 is that it accounts for the time during change-overs (90 seconds), and some matches have shorter work periods than 10 seconds as well. Therefore, to appropriately cover all environments seen during tennis matches it is appropriate to cycle your tennis-specific training using a 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest ratio. In addition to the work - rest cycle concept, the term specificity is often applied. Specificity involves training the athlete in a manner most similar to the actual demands of the sport. It means using movement patterns, distances, and times similar to tennis play. For example, running 5 miles builds aerobic conditioning, but it has very little specificity to tennis play. Performing tennis-specific endurance training involves a number of short-duration, multidirectional movements at high intensity with the work - rest ratios mentioned earlier. This training is more specific to tennis than running at a slow pace for 5 miles.

Anaerobic training techniques in tennis use both concepts of work - rest cycle and specificity. Drills and activities used to improve anaerobic power follow the 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle and include relatively short-duration, multidirectional movement patterns. The characteristics of tennis play that can be incorporated into tennis-specific training include the following:

- A tennis point usually includes four or five directional changes.

- Most tennis points last fewer than 10 seconds.

- Tennis players always carry their rackets during points.

- Players seldom run more than 30 feet (9 m) in one direction during a point.

- Movement patterns contain acceleration and controlled deceleration.

These characteristics can be incorporated into a hitting session with a ball machine or coach (table 10.1). The player takes a 90-second sit-down break between each series. During the 90-second break, the feeder must pick up the balls and prepare for the next series. Heart rate can be recorded at the start and end of each 90-second break between series. The goal would be to reduce heart rate significantly during that time period. Also, you could set up targets to hit within. If so, record the number of balls hit outside the designated target areas. The goal is to keep errors to a minimum during all sequences.

Tennis-specific drills to improve on-court movement and footwork as well as anaerobic power are included in chapters 5 and 6. Any exercise that includes a relatively short period of maximal-intensity work followed by a period of recovery that is approximately two times longer than the period of work stresses the anaerobic energy system. General anaerobic training drills for tennis include classic on-court movement drills such as cross cones (chapter 6) and line drills such as the sideways shuffle, alley hop, and spider run (chapter 6). To make these general anaerobic training drills more specific to tennis, perform them with a tennis racket in hand as you would do when you play tennis.

Another beneficial training exercise is also sometimes used as a fitness test for tennis. The MK drill (described as a test in chapter 4) is one of the most useful training exercises to develop tennis-specific endurance; it follows ratios of work to rest for tennis and covers distances seen on the tennis court; you sprint 36 feet (10.97 m) in one direction before turning. The MK drill is a good drill that takes 15 to 20 minutes and can be performed on the tennis court once or twice per week as part of a structured periodized training program to help improve tennis-specific endurance.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Shoulder Injuries in Tennis

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched.

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched. When this happens over and over again, it can injure the tendon. The labrum or cartilage in the shoulder socket also can become injured (torn) in overhead athletes, especially those with very loose shoulders and poor rotator cuff strength and shoulder stability. Many of the shoulder injuries seen in tennis can be prevented with a proper stretching and strengthening program.

Stretches to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

The two most important shoulder stretches for tennis players are the cross-arm stretch and the sleeper stretch. Research shows that using these stretches as part of a regular program will improve the range of motion of internal rotation.

Preventive Shoulder Stretches

As with any stretch, perform them after tennis play and complete 2 or 3 repetitions of each stretch, holding each for 20 to 30 seconds. This will improve or maintain flexibility in the shoulder.

Posterior Shoulder Stretch (Cross-Arm Stretch)

Focus

Improve flexibility of the muscles in the back of the shoulder and back of the shoulder joint capsule.

Procedure

- Stand next to a doorway or fence. Raise your racket arm to shoulder level. Brace the side of your shoulder and shoulder blade against the wall or fence to keep the shoulder blade from sliding forward when you begin the stretch.

- Using the other hand, grab the outside of the elbow of your racket hand and pull your arm across your chest (figure 12.3). You should feel the stretch in the back of your shoulder.

- Hold the position, then switch sides.

Note

If you feel a pinching sensation in the front of your shoulder, discontinue this stretch and use the sleeper stretch to accomplish a similar stretch for this portion of the shoulder.

Cross-arm stretch.

Strengthening Exercises to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

Increasing muscular endurance and building a base level of strength in the rotator cuff and upper back should be the goals of any shoulder-strengthening program. The following exercises can be used to strengthen the back, or posterior part, of the rotator cuff. Perform each of these exercises slowly and with proper form.

Begin by performing these exercises using three sets of 15 to 20 repetitions. However, you must maintain proper technique when performing these exercises, even on the 20th repetition in the third set. Do not hesitate to do fewer repetitions or sets if you cannot maintain proper technique; it is better to do fewer repetitions correctly than more repetitions incorrectly. When done correctly, these exercises should not produce pain, just a feeling of burning around the shoulder. These exercises should be done after tennis play, to prevent fatiguing the shoulder prior to tennis play. The exercises are most important to be done with the dominant (tennis playing) shoulder.

Shoulder Strengthening Exercises With Weights

Most young players need to use only a 1-pound (0.45-kg) weight to start strengthening the shoulder muscles. Remember, these muscles are small, and tennis players do not need to lift a lot of weight to strengthen them appropriately. In fact, if using too much weight, players will substitute and use muscles other than the rotator cuff to perform the exercise.

Older, more experienced players will experience significant muscular fatigue doing these exercises using a 1.5- or 2-pound (0.7- or 0.9-kg) weight if the exercises are done correctly. Control the weight as you lift it (while muscles are shortening) and when you lower it (while muscles are lengthening), because this control prepares the muscle for the specific performance demands encountered during tennis play. As you get stronger, increase the weight in 1/2-pound (0.2-kg) increments, but only after you can do all three sets without significant fatigue and without using other parts of your body to compensate.

Sidelying External Rotation

Focus

Strengthen the external rotator muscles of the shoulder.

Procedure

- Lie on one side with your working arm (top arm) at your side and a small pillow between your arm and body. Hold a small dumbbell in the hand of your working arm.

- Keeping the elbow of your working arm bent and fixed to your side, raise your arm into external rotation until it is just short of pointing straight up (figure 12.5).

- Slowly lower the arm to the starting position.

- Repeat the exercise on the other side.

Sidelying external rotation.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Flexibility Training

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following: Stretching may not feel particularly good. The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following:

- Stretching may not feel particularly good.

- The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

- Most players have been given no specific individualized guidelines as to how, why, what, and when to stretch.

- Many coaches emphasize stretching less than the other components of conditioning

The term flexibility can be defined as the degree of extensibility of the soft tissue structures surrounding the joint, such as muscles, tendons, and connective tissue. Two main types of flexibility exist. Static flexibility describes the measured range of motion about a joint or series of joints, and dynamic flexibility refers to the active motion about a joint or series of joints. Dynamic flexibility is limited by the resistance to motion of the joint structures, the ability of the soft connective tissues to deform, and neuromuscular components.

Factors influencing flexibility include heredity, neuromuscular components, and tissue temperature. In regard to heredity, body design determines overall flexibility potential. While most people tend to be relatively inflexible, a small few are hyperflexible. Aspects of heredity and body design that affect flexibility potential include the shape and orientation of joint surfaces, as well as the physiological characteristics of the joint capsule, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. In addition, because of the nature of the movements performed while playing tennis and from the repetitive nature of these stresses, some areas of the tennis player's body can be very tight and inflexible. These areas include the hamstrings, low back, and muscles in the back of the shoulder. At the same time, other areas in the tennis player's body may be overly flexible, such as the front of the shoulder (external rotation). These adaptations are the result of many years of playing tennis.

Sleeper Stretch

Focus

Improve flexibility of the shoulder rotators and upper-back (scapular) muscles.

Procedure

- Lie on your dominant shoulder as you would when sleeping on your side.

- Place your dominant arm directly in front of you at a 90-degree angle, keeping the elbow bent 90 degrees as well.

- Using your other arm, push your hand down toward your feet, internally rotating your shoulder (figure 5.15).

- Hold the position for 15 to 30 seconds, then repeat the stretch on the other side.

Note

You can make this stretch even more intense by placing your chin against the front of the shoulder you are lying on, pressing it down even more to provide greater stabilization to increase the stretch.

Sleeper stretch.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Major Movements

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot.

Split Step

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot. For example, a right-handed player who is preparing to hit a forehand would land on the left foot first (figure 3.2a). Before the right foot touches the ground, the athlete subtly rotates the foot externally toward the intended movement toward the ball. For a right-handed player, this would result in the right foot landing and pointing outward (figure 3.2b). This movement pattern has been a natural evolution to improve the athletes' ability to react to the incoming ball and maximize their ratio of movement to time.

|  |

Split step landing: (a) loading on left foot; (b) right hip rotation.

Major Movements

Although thousands of movements occur in a single tennis match, a certain number of movements are common to the sport of tennis. Becoming proficient in these major movements will help you become a better mover on the tennis court and therefore a better overall player. Training for tennis requires that you repeat good quality movement patterns on a regular basis. Having a clear understanding of the correct movement patterns and how best to train to improve them will speed your improvement and make you more efficient on the court. Over time it can also reduce the chance of injury resulting from inefficient movements, poor loading patterns, and overuse as a result of inappropriate mechanics.

The jab step is defined as stepping first with the lead foot in the direction of the oncoming ball (figure 3.3).

Jab step.

The pivot step involves pivoting on the lead foot while turning the hip toward the ball and making the first step toward the ball with the opposite leg (figure 3.4).

Pivot step.

The drop step (i.e., run-around forehand) involves explosively turning the hips and dropping the outside leg behind the body to instigate the first movement when working on setting up for a run-around forehand stroke (figure 3.5).

Drop step.

Save

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Tennis and Energy Systems

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session.

Applying the energy system continuum to tennis is easy and helps illustrate the reason that both anaerobic and aerobic conditioning are necessary for enhancing tennis performance. Because tennis ultimately involves repetitive muscular contractions and exertion, the aerobic energy system provides the baseline energy production over the duration of a tennis match or practice session. Aerobic fitness is also important for recovery following a strenuous baseline rally, bursts of movement, and maximal skills such as executing a serve-and-volley sequence or an overhead shot.

Anaerobic energy production is required for maximal activities during points. Testing (in the form of treadmill tests and intermittent endurance runs) on elite tennis players indicates high levels of aerobic fitness. Sprinting and agility tests indicate superior anaerobic power. These results explain a player's ability to maximally sprint from side to side during a baseline rally and then, after 20 to 25 seconds rest, do it again. Athletes with better aerobic fitness levels can clear the accumulated lactic acid from the working muscles more rapidly than players with less aerobic fitness. Likewise, athletes with greater aerobic power can run faster and jump higher because of greater energy stores in the trained muscle. However, tennis requires a balance, and the best tennis players have high levels of both anaerobic and aerobic fitness. Training needs to be structured appropriately to accurately match the demands of the sport of tennis and the player's game style.

Tennis Training for Anaerobic Power

Analysis of tennis matches generally determines that the average point lasts less than 10 seconds; some points can last 20 to 30 seconds. Most players' average rest time is 18 to 20 seconds, with a maximum allowable rest time between points being 20 or 25 seconds, depending on competition rules. The ratio of work time to rest time is termed the work - rest cycle. A 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle is most representative of the physiological activity pattern experienced during tennis. This means that for every 1 second of work, you will have 2 to 5 seconds of rest. In practical terms, a 10-second point would result in a 20- to 50-second rest. The reason that some matches involve a work - ratio of 1:5 is that it accounts for the time during change-overs (90 seconds), and some matches have shorter work periods than 10 seconds as well. Therefore, to appropriately cover all environments seen during tennis matches it is appropriate to cycle your tennis-specific training using a 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest ratio. In addition to the work - rest cycle concept, the term specificity is often applied. Specificity involves training the athlete in a manner most similar to the actual demands of the sport. It means using movement patterns, distances, and times similar to tennis play. For example, running 5 miles builds aerobic conditioning, but it has very little specificity to tennis play. Performing tennis-specific endurance training involves a number of short-duration, multidirectional movements at high intensity with the work - rest ratios mentioned earlier. This training is more specific to tennis than running at a slow pace for 5 miles.

Anaerobic training techniques in tennis use both concepts of work - rest cycle and specificity. Drills and activities used to improve anaerobic power follow the 1:2 to 1:5 work - rest cycle and include relatively short-duration, multidirectional movement patterns. The characteristics of tennis play that can be incorporated into tennis-specific training include the following:

- A tennis point usually includes four or five directional changes.

- Most tennis points last fewer than 10 seconds.

- Tennis players always carry their rackets during points.

- Players seldom run more than 30 feet (9 m) in one direction during a point.

- Movement patterns contain acceleration and controlled deceleration.

These characteristics can be incorporated into a hitting session with a ball machine or coach (table 10.1). The player takes a 90-second sit-down break between each series. During the 90-second break, the feeder must pick up the balls and prepare for the next series. Heart rate can be recorded at the start and end of each 90-second break between series. The goal would be to reduce heart rate significantly during that time period. Also, you could set up targets to hit within. If so, record the number of balls hit outside the designated target areas. The goal is to keep errors to a minimum during all sequences.

Tennis-specific drills to improve on-court movement and footwork as well as anaerobic power are included in chapters 5 and 6. Any exercise that includes a relatively short period of maximal-intensity work followed by a period of recovery that is approximately two times longer than the period of work stresses the anaerobic energy system. General anaerobic training drills for tennis include classic on-court movement drills such as cross cones (chapter 6) and line drills such as the sideways shuffle, alley hop, and spider run (chapter 6). To make these general anaerobic training drills more specific to tennis, perform them with a tennis racket in hand as you would do when you play tennis.

Another beneficial training exercise is also sometimes used as a fitness test for tennis. The MK drill (described as a test in chapter 4) is one of the most useful training exercises to develop tennis-specific endurance; it follows ratios of work to rest for tennis and covers distances seen on the tennis court; you sprint 36 feet (10.97 m) in one direction before turning. The MK drill is a good drill that takes 15 to 20 minutes and can be performed on the tennis court once or twice per week as part of a structured periodized training program to help improve tennis-specific endurance.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Shoulder Injuries in Tennis

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched.

The most common injury site in the shoulder is not the rotator cuff muscles themselves but rather the tendons that attach these muscles to the upper arm. There is not a lot of space inside the shoulder. When muscles fatigue or improper technique is used, it is very easy for one of the rotator cuff tendons that pass through this space to get pinched. When this happens over and over again, it can injure the tendon. The labrum or cartilage in the shoulder socket also can become injured (torn) in overhead athletes, especially those with very loose shoulders and poor rotator cuff strength and shoulder stability. Many of the shoulder injuries seen in tennis can be prevented with a proper stretching and strengthening program.

Stretches to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

The two most important shoulder stretches for tennis players are the cross-arm stretch and the sleeper stretch. Research shows that using these stretches as part of a regular program will improve the range of motion of internal rotation.

Preventive Shoulder Stretches

As with any stretch, perform them after tennis play and complete 2 or 3 repetitions of each stretch, holding each for 20 to 30 seconds. This will improve or maintain flexibility in the shoulder.

Posterior Shoulder Stretch (Cross-Arm Stretch)

Focus

Improve flexibility of the muscles in the back of the shoulder and back of the shoulder joint capsule.

Procedure

- Stand next to a doorway or fence. Raise your racket arm to shoulder level. Brace the side of your shoulder and shoulder blade against the wall or fence to keep the shoulder blade from sliding forward when you begin the stretch.

- Using the other hand, grab the outside of the elbow of your racket hand and pull your arm across your chest (figure 12.3). You should feel the stretch in the back of your shoulder.

- Hold the position, then switch sides.

Note

If you feel a pinching sensation in the front of your shoulder, discontinue this stretch and use the sleeper stretch to accomplish a similar stretch for this portion of the shoulder.

Cross-arm stretch.

Strengthening Exercises to Prevent Shoulder Injuries

Increasing muscular endurance and building a base level of strength in the rotator cuff and upper back should be the goals of any shoulder-strengthening program. The following exercises can be used to strengthen the back, or posterior part, of the rotator cuff. Perform each of these exercises slowly and with proper form.

Begin by performing these exercises using three sets of 15 to 20 repetitions. However, you must maintain proper technique when performing these exercises, even on the 20th repetition in the third set. Do not hesitate to do fewer repetitions or sets if you cannot maintain proper technique; it is better to do fewer repetitions correctly than more repetitions incorrectly. When done correctly, these exercises should not produce pain, just a feeling of burning around the shoulder. These exercises should be done after tennis play, to prevent fatiguing the shoulder prior to tennis play. The exercises are most important to be done with the dominant (tennis playing) shoulder.

Shoulder Strengthening Exercises With Weights

Most young players need to use only a 1-pound (0.45-kg) weight to start strengthening the shoulder muscles. Remember, these muscles are small, and tennis players do not need to lift a lot of weight to strengthen them appropriately. In fact, if using too much weight, players will substitute and use muscles other than the rotator cuff to perform the exercise.

Older, more experienced players will experience significant muscular fatigue doing these exercises using a 1.5- or 2-pound (0.7- or 0.9-kg) weight if the exercises are done correctly. Control the weight as you lift it (while muscles are shortening) and when you lower it (while muscles are lengthening), because this control prepares the muscle for the specific performance demands encountered during tennis play. As you get stronger, increase the weight in 1/2-pound (0.2-kg) increments, but only after you can do all three sets without significant fatigue and without using other parts of your body to compensate.

Sidelying External Rotation

Focus

Strengthen the external rotator muscles of the shoulder.

Procedure

- Lie on one side with your working arm (top arm) at your side and a small pillow between your arm and body. Hold a small dumbbell in the hand of your working arm.

- Keeping the elbow of your working arm bent and fixed to your side, raise your arm into external rotation until it is just short of pointing straight up (figure 12.5).

- Slowly lower the arm to the starting position.

- Repeat the exercise on the other side.

Sidelying external rotation.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Flexibility Training

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following: Stretching may not feel particularly good. The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

Flexibility training is often the most overlooked component of a quality conditioning program. Some of the reasons people do not adhere to flexibility programs include the following:

- Stretching may not feel particularly good.

- The on-court benefits are not obvious to the player.

- Most players have been given no specific individualized guidelines as to how, why, what, and when to stretch.

- Many coaches emphasize stretching less than the other components of conditioning

The term flexibility can be defined as the degree of extensibility of the soft tissue structures surrounding the joint, such as muscles, tendons, and connective tissue. Two main types of flexibility exist. Static flexibility describes the measured range of motion about a joint or series of joints, and dynamic flexibility refers to the active motion about a joint or series of joints. Dynamic flexibility is limited by the resistance to motion of the joint structures, the ability of the soft connective tissues to deform, and neuromuscular components.

Factors influencing flexibility include heredity, neuromuscular components, and tissue temperature. In regard to heredity, body design determines overall flexibility potential. While most people tend to be relatively inflexible, a small few are hyperflexible. Aspects of heredity and body design that affect flexibility potential include the shape and orientation of joint surfaces, as well as the physiological characteristics of the joint capsule, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. In addition, because of the nature of the movements performed while playing tennis and from the repetitive nature of these stresses, some areas of the tennis player's body can be very tight and inflexible. These areas include the hamstrings, low back, and muscles in the back of the shoulder. At the same time, other areas in the tennis player's body may be overly flexible, such as the front of the shoulder (external rotation). These adaptations are the result of many years of playing tennis.

Sleeper Stretch

Focus

Improve flexibility of the shoulder rotators and upper-back (scapular) muscles.

Procedure

- Lie on your dominant shoulder as you would when sleeping on your side.

- Place your dominant arm directly in front of you at a 90-degree angle, keeping the elbow bent 90 degrees as well.

- Using your other arm, push your hand down toward your feet, internally rotating your shoulder (figure 5.15).

- Hold the position for 15 to 30 seconds, then repeat the stretch on the other side.

Note

You can make this stretch even more intense by placing your chin against the front of the shoulder you are lying on, pressing it down even more to provide greater stabilization to increase the stretch.

Sleeper stretch.

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Major Movements

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot.

Split Step

Early descriptions of the split step reported both feet landing on the court simultaneously after the athlete made a small jump and then reacted left, right, forward, or backward, depending on where the ball was hit. Now it is known that good athletes react in the air during the split and land on the foot farthest from their intended target a split second ahead of their other foot. For example, a right-handed player who is preparing to hit a forehand would land on the left foot first (figure 3.2a). Before the right foot touches the ground, the athlete subtly rotates the foot externally toward the intended movement toward the ball. For a right-handed player, this would result in the right foot landing and pointing outward (figure 3.2b). This movement pattern has been a natural evolution to improve the athletes' ability to react to the incoming ball and maximize their ratio of movement to time.

|  |

Split step landing: (a) loading on left foot; (b) right hip rotation.

Major Movements

Although thousands of movements occur in a single tennis match, a certain number of movements are common to the sport of tennis. Becoming proficient in these major movements will help you become a better mover on the tennis court and therefore a better overall player. Training for tennis requires that you repeat good quality movement patterns on a regular basis. Having a clear understanding of the correct movement patterns and how best to train to improve them will speed your improvement and make you more efficient on the court. Over time it can also reduce the chance of injury resulting from inefficient movements, poor loading patterns, and overuse as a result of inappropriate mechanics.

The jab step is defined as stepping first with the lead foot in the direction of the oncoming ball (figure 3.3).

Jab step.

The pivot step involves pivoting on the lead foot while turning the hip toward the ball and making the first step toward the ball with the opposite leg (figure 3.4).

Pivot step.

The drop step (i.e., run-around forehand) involves explosively turning the hips and dropping the outside leg behind the body to instigate the first movement when working on setting up for a run-around forehand stroke (figure 3.5).

Drop step.

Save

Save

Learn more about Complete Conditioning for Tennis.

Tennis and Energy Systems