- Home

- Psychology of Sport and Exercise

- Kinesiology/Exercise and Sport Science

- Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology

Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology is a comprehensive resource that offers both students and professionals the opportunity to hone their skills to help their clients, starting with the initial consultation and lasting through a long-term relationship. In this text, Jim Taylor and a team of sport psychology experts help practitioners gain a deep understanding of assessment in order to build trusting relationships and effective intervention plans that address the needs and goals of their clients.

Part I of Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology covers topics such as the importance of assessment, the appropriateness of qualitative and quantitative assessment, ethical issues that can arise from assessment, and the impact of diversity in the use of assessment. Part II introduces readers to six ways that consultants can assess athletes: mental health screening, personality tests, sport-specific objective measures, interviewing, observation, and applied psychophysiology. Chapters in this section explain the strengths and weaknesses of each approach—for example, when traditional pencil-and-paper and observation approaches may be more appropriate than interviewing—and offer consultants a more complete toolbox of assessments to use when working with athletes. Part III addresses special issues, such as career transition, talent identification, and sport injury and rehabilitation. One chapter is devoted to the hot-button issue of sport-related concussions.

Tables at the end of most chapters in parts II and III contain invaluable information about each of the assessment tools described, including its purpose, publication details, and how to obtain it. Chapters also contain sidebars that provide sample scenarios, recommended approaches, and exercises to use with clients.

Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology works toward two main goals. The first is to help consultants gain a complete understanding of their clients through the use of a broad range of assessment tools. The second is to show consultants how to ethically and effectively use assessments to develop a comprehensive understanding of their clients, thus enabling them to assist their clients in achieving their competitive and personal goals.

Part I: Foundation of Assessment in Sport Psychology Consulting

Chapter 1: Importance of Assessment in Sport Psychology Consulting

Jim Taylor

Assessment Terminology

Purpose of Assessment

Practical Value and Use of Assessment

Assessment Skill Sets

Assessment Is Judgment

Assessment Toolbox

Choosing Assessment Tools

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 2: Science of Sport Psychology Assessment

Anita N. Lee and Jim Taylor

Assessment for Individuals Versus Groups

Validity and Reliability of Assessments

Determining the Value of Sport Psychology Assessments

Critical Evaluation of Assessment Research

Specificity of Assessment Instruments

Quantitative and Qualitative Assessments

Assessment Myths

Creating Your Own Assessments

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 3: Ethical Issues in Sport Psychology Assessment

Marshall Mintz and Michael Zito

Ethical Principles

Ethical Guidelines

When Ethical Dilemmas Arise

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 4: Diversity in Sport Psychology Assessment

Latisha Forster Scott, Taunya Marie Tinsley, Kwok Ng, Jenny Lind Withycombe, and Melanie Poudevigne

Marginalization of Cultural Diversity in Sport Psychology and Assessment

Multicultural Sport Psychology Competencies

Overview of Multicultural Assessment

Assessment Tools

Implications for Consultants

Future Directions for Professional Development

Chapter Takeaways

Part II: Assessment Tools

Chapter 5: Mental Health Screening: Identifying Clinical Issues

Erin N. J. Haugen, Jenni Thome, Megan E. Pietrucha, and M. Penny Levin

Stress

Depression and Suicide

Anxiety

Disordered Eating and Eating Disorders

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Substance Use and Abuse

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 6: Personality Tests: Understanding the Athlete as Person

James Tabano and Steve Portenga

History of Personality Assessment in Sport

Self-Esteem

Perfectionism

Fear of Failure

Need for Control

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 7: Inventories: Using Objective Measures

Graig M. Chow and Todd A. Gilson

Importance of Practicality When Choosing Assessments

Benefits of Objective Measures in Consulting with Athletes

Assessment Tools for Individual Athletes

Mental Skills and Techniques

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 8: Interviewing: Asking the Right Questions

Jim Taylor, Duncan Simpson, and Angel L. Brutus

Importance of Client Information

Best Practices of Interviewing

Sport Interviewing Protocol

Sport-Clinical Intake Protocol

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 9: Observation: Seeing Athletes on the Field

Tim Holder, Stacy Winter, and Brandon Orr

Underlying Professional Philosophy

Use and Benefits of Direct Observation

Categories of Observational Assessment

Observation Assessment Tools

Limitations and Concerns

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 10: Applied Psychophysiology: Using Biofeedback, Neurofeedback, and Visual Feedback

Sheryl Smith, Melissa Hunfalvay, Tim Herzog, and Pierre Beauchamp

Stress Response and Self-Regulation

Benefits of Psychophysiological Assessment

Biofeedback and Neurofeedback Assessment

Visual Assessment

Chapter Takeaways

Part III: Special Issues in Assessment

Chapter 11: Coach, Team, and Parent Assessments

Andy Gillham, Travis Dorsch, Barbara J. Walker, and Jim Taylor

Coach Assessment

Team Assessment

Parent Assessment

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 12: Talent Identification

Barbara B. Meyer, Stacy L. Gnacinski, and Teresa B. Fletcher

Talent Identification Models and Research

Assessment of Psychosocial Factors Linked to Talent in Sport

Behavioral Observation

Qualitative Interviews

Implications for Consultants

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 13: Sport Injury, Rehabilitation, and Return to Sport

Monna Arvinen-Barrow, Jordan Hamson-Utley, and J.D. DeFreese

Assessment of Psychosocial Factors Linked to Sport Injury

Assessment for Musculoskeletal Sport Injury

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 14: Assessment and Management of Sport-Related Concussions

Robert Conder and Alanna Adler Conder

SRC Consultation Essentials

Components of SRC Assessment

Role of Assessment in RTL

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 15: Career Transition

Claire-Marie Roberts and Marisa O. Davis

Athletic Career Transitions

Key Issues in Consultation and Recommendations for Assessment

Retirement

Postsport Career Planning and Development

Limitations and Concerns

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 16: Systems Approach to Consulting in Sport Organizations

Charles A. Maher and Jim Taylor

Systems Approach

Identifying Assessment Needs

Determining Readiness for Assessment Services

Chapter Takeaways

Chapter 17: Consultant Effectiveness

Stephen P. Gonzalez, Ian Connole, Angus Mugford, and Jim Taylor

Benefits of Assessing Consultant Effectiveness

Assessing Consultant Effectiveness

Chapter Takeaways

Jim Taylor, PhD, CC-AASP, is an internationally recognized consultant and presenter on the psychology of sport and parenting. He has served as a consultant for the U.S. and Japanese ski teams, the United States Tennis Association, and USA Triathlon. He has worked with professional and world-class athletes in tennis, skiing, cycling, triathlon, track and field, swimming, golf, and many other sports. He has been invited to lecture by the Olympic Committees of Spain, France, Poland, and the United States, and he has been a consultant to the athletic departments at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley. Taylor has authored or edited 18 books, published more than 800 articles, and given more than 1,000 workshops and presentations throughout North and South America, Europe, and the Middle East.

A former world-ranked alpine ski racer, Taylor is a second-degree black belt and certified instructor in karate, a marathon runner, and an Ironman triathlete. He earned his PhD in psychology from the University of Colorado. He is a former associate professor in the school of psychology at Nova University and a former clinical associate professor in the sport and performance psychology graduate program at the University of Denver. Taylor is currently an adjunct faculty member at the University of San Francisco.

Visual Assessment

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another.

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another. An athlete's ability to track objects and react appropriately develops with experience and at an individualized pace. Visual attention, perceptual information processing, and response selection can be disrupted by anxiety and distraction. Training to improve the allocation of attentional resources can enhance the development of these skills and protect them against the effects of pressure (Vine, Moore, & Wilson, 2014).

Benefits of Visual Search Assessment

Effective use of visual gaze behaviors (see table 10.2) and, in turn, the assessment of perceptual-cognitive skills, provides the following benefits:

- Anticipation: Looking at the right spot at the right time and making sense of what is seen enhances the ability to predict future events (Farrow & Abernathy, 2002; Savelsbergh, Williams, van der Kamp, & Ward, 2002).

- Attention: Efficient use of attentional resources involves focusing on the most important cues while ignoring distractions to take in the minimum amount of essential information. This results in the most efficient processing (Williams & Davids, 1998).

- Memory:Synthesis of past events into meaningful chunks of information enables athletes to employ effective strategies and tactics (Abernathy, Baker, & Cote, 2005).

- Pattern recognition:The ability to read plays based on experience (North & Williams, 2008) allows athletes to synthesize patterns and learn from them.

- Problem solving: The ability to conceptually organize thoughts based on visual information processing influences athletes' ability to determine what has worked and what hasn't (McPherson & Kernodle, 2003).

- Decision making: Athletes with effective perceptual-cognitive skills can read, anticipate, and make accurate decisions quickly (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, Mazyn, & Philippaerts, 2007).

- Situational awareness: The ability to perceive and understand the environment (Caserta & Abrams, 2007) improves as athletes know what is visually important and what to ignore.

- Motor efficiency: The result of effective perception and cognition in sport is often motor efficiency (Williams & Ericsson, 2007).

- Stress reduction: A further benefit of effective perceptual-cognitive skills is reduced stress (Gerstenberg, 2012). Being more focused and reducing information processing can lead to a cascading reduction in stress (Vickers & Lewinski, 2012).

- Alertness and resilience: The ability to stay alert over time is an important benefit of perceptual-cognitive skills. In any situation with a potential for fatigue, the more efficient the perceptions, cognitions, and motor responses, the greater the alertness and resilience (Williams, Hodges, North, & Barton, 2006).

Eye Tracking

Unlike biomechanical changes, which are readily observable, visual and cognitive processes are not so easily scrutinized. An eye tracker is a special pair of glasses that records athletes' point of gaze upon the environment, taking pictures of the location of the gaze at various frame rates (e.g., 60 times per second), similar to a camera. Eye-tracking technology enables us to make three types of visual feedback assessments.

Gaze Location

An eye tracker examines the location of a person's focal vision (gaze point) within an environment to determine if the subject is attending to the appropriate cues (see figure 10.4). For example, research has demonstrated that looking at the contact point when returning a serve in tennis assists in ball tracking (Murray & Hunfalvay, 2016). In baseball, the pitcher's hand positioning on the ball helps hitters determine the type of pitch that will be thrown (Takeuchi & Inomata, 2009).

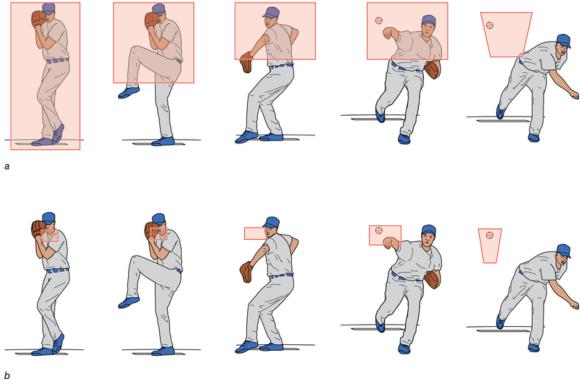

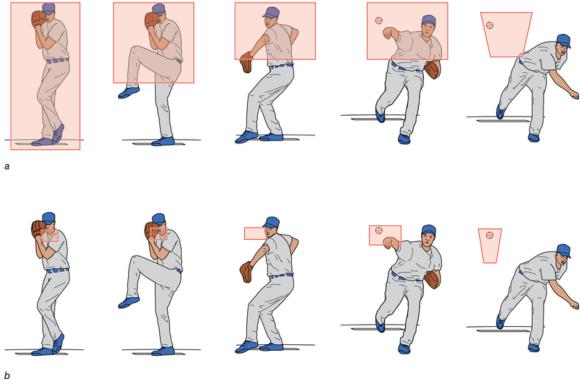

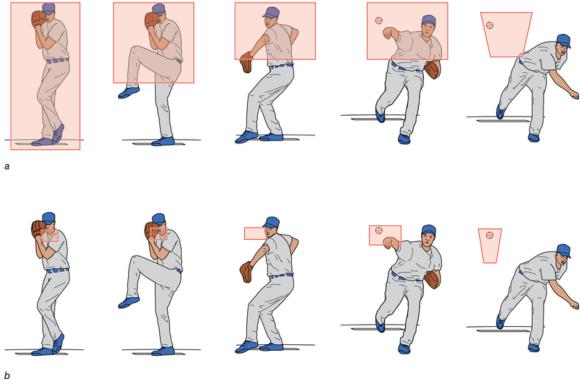

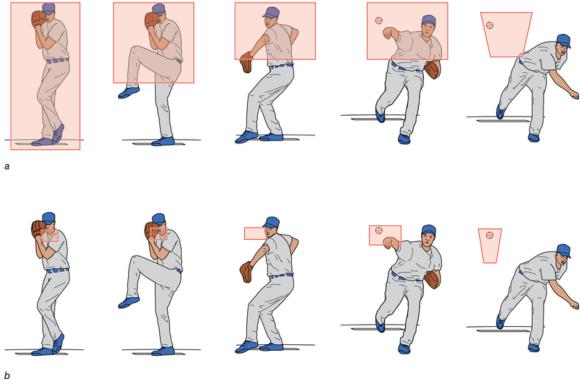

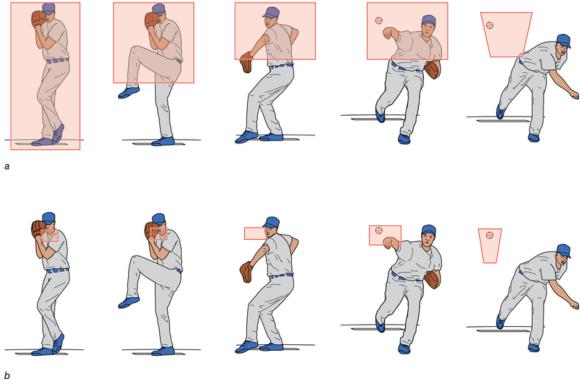

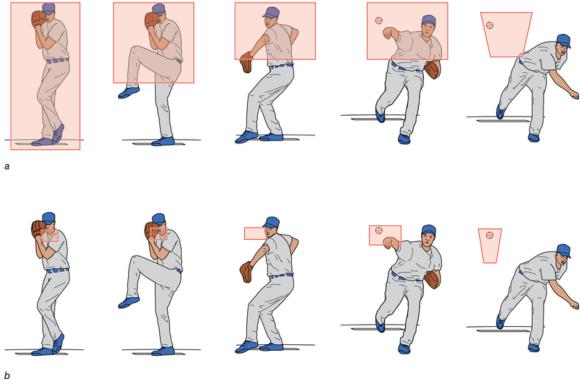

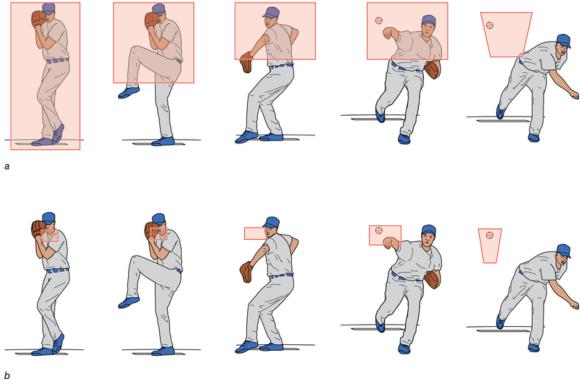

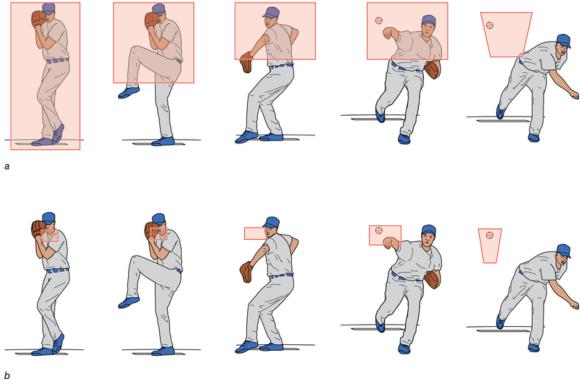

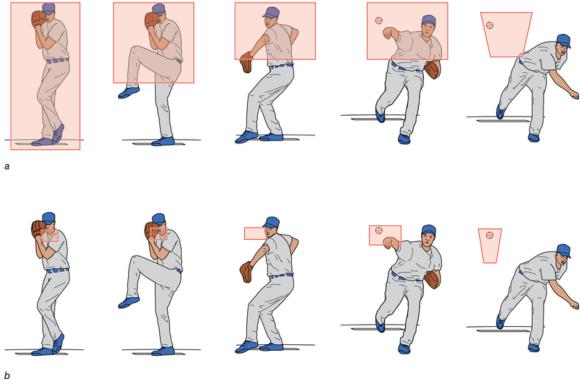

(a) Minor League Baseball aggregate visual search cues versus (b) Major League Baseball aggregate visual search cues. Major leaguers demonstrate attention to fewer and more localized visual cues.

Assessment of visual feedback gaze location using eye trackers is based on research using temporal occlusion (Farrow, Abernathy, & Jackson, 2005), where the task being viewed is stopped at various points before completion and athletes are asked to extrapolate information about what will happen in the future, such as the direction a ball will travel. Visual feedback is also based on cue occlusion (also called spatial occlusion) research (Muller & Abernathy, 2006), where important cues are blocked from view to determine their impact on performance. These assessment paradigms measure performance outcomes using additional tools such as pressure-sensitive floor mats and infrared beams that detect response time (Williams & Ericsson, 2005).

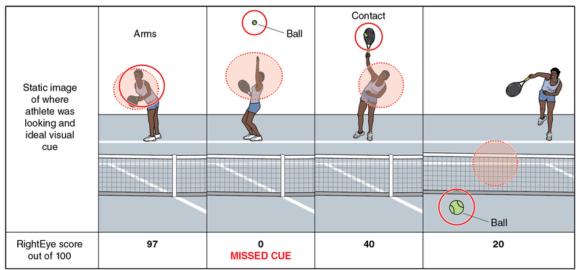

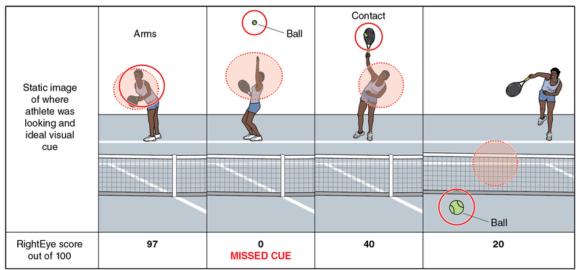

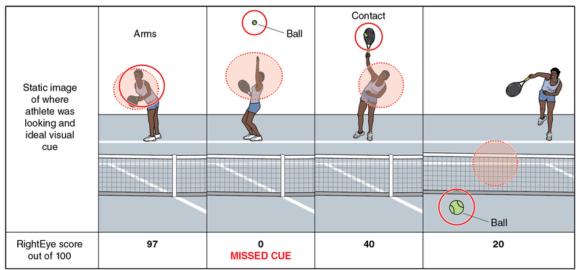

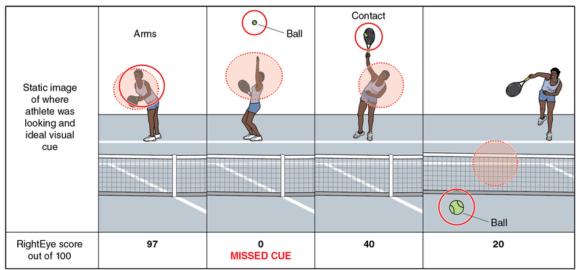

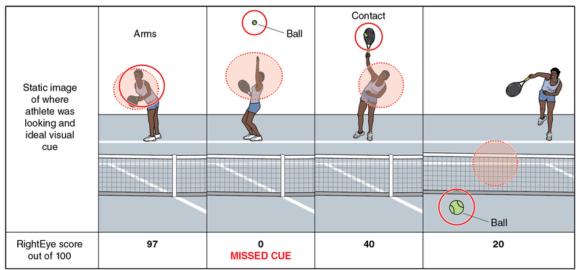

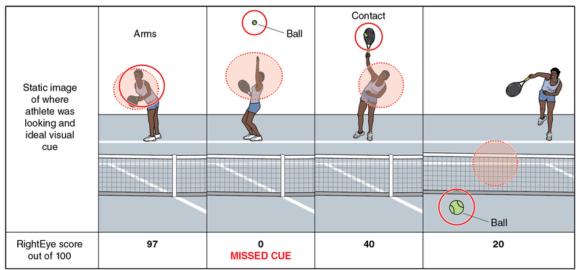

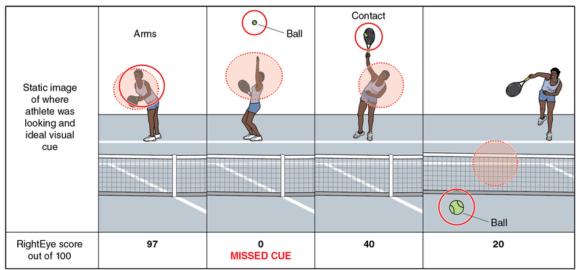

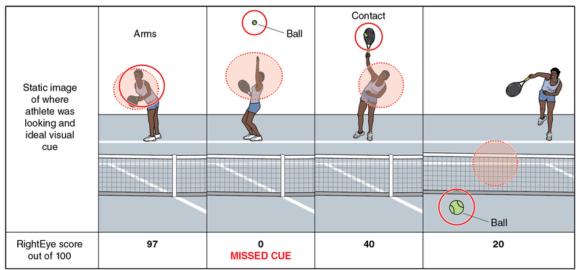

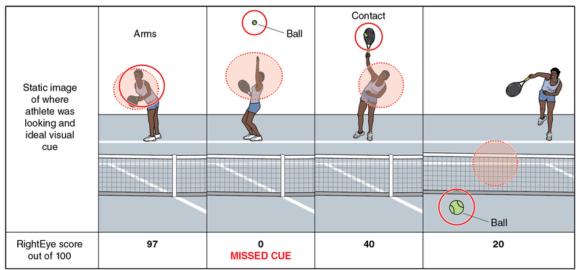

Common assessments of gaze error include missed cues, scattered visual search, and late tracking. Missed cues (see figure 10.5) are often caused by a lack of perceptual-cognitive expertise or a failure to understand what the cue reveals, why it is important, and how it can be used to improve performance.

Gaze location and important visual cues. Solid circles represent important visual cues. Dotted circles represent the athlete's actual gaze location. Convergence of the two is scored out of a possible 100. Here, the missed cue in the toss phase results in failure to target the contact point and late ball tracking.

A second common error in gaze location is a scattered visual search pattern. Figure 10.4a demonstrates the wider visual search area of a less experienced baseball player. Research demonstrates that experts exhibit fewer fixations of longer duration compared with less skilled performers (Gegenfurtner, Lehtinen, & Säljö, 2011; Mann, Ward, Williams, & Janelle, 2007). Less skilled athletes who display a scattered search pattern end up processing too many cues because they are unsure where to look and what is important.

Late tracking is another common error in gaze location. This occurs especially in fast-moving, open-skilled sports when athletes start late and do not have time to catch up. This can be due to a lack of expertise or a lack of attention or readiness. Late tracking in the beginning of a sequence has negative consequences that multiply further along the biomechanical phases.

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

Purpose of Assessment

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people.

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people. Assessment also tells clients a great deal about who you are and how you work and about your field more broadly.

Understanding the Person as an Athlete

The most obvious part of understanding involves the person as an athlete - that is, what makes her tick in training and competition. This understanding involves a wide range of psychology, including how athletes think, the emotions they experience, and the way they behave, particularly in the heat of competition. Specific components of athletes' psychology consist of their attitudes toward and relationships with success, failure, expectations, and competition. Mental factors that must be understood include motivation, confidence, intensity (e.g., energy, arousal, anxiety), focus, and emotions. Athletes' psychology can also include the mental tools athletes use in their preparation and performance, such as goal setting, mental imagery, routines, self-talk, and breathing. Furthermore, it can include their relationships with teammates, coaches, competitors, officials, and, importantly for young athletes, parents.

Even though consultants may be focusing on athletes' psychology, a true understanding of athletes must also include every area that affects performance, such as physical conditioning, technique, tactics, equipment, and team dynamics. Consultants need to know athletes' strengths and weaknesses in these areas, as well as how they approach their training and competitive performances.

Understanding the Athlete as a Person

In sport psychology there may be a tendency to view clients as athletes alone, forgetting that they are first and foremost people. For example, when athletes enter the field of competition, they don't leave their personness, so to speak, on the sidelines. Whoever they are as people will be expressed on the field as they pursue their athletic goals. Whatever weaknesses they hold as people, such as doubts, worries, or fears, will come out in their athletic performance. In a more positive light, whatever strengths they possess as people - whether determination, confidence, or resilience - will also emerge in practice and competition.

Just thinking about exploring the depth and breadth of a client's internal athletic life, much less her personal psyche, can be a daunting task. The athlete as person encompasses every aspect of who athletes are:

- Their innate dispositions, temperament, and tendencies (e.g., introverted or extroverted, stoic or emotional)

- Their values and priorities that act as signposts for their aspirations and goals

- Their beliefs about themselves (e.g., self-assessment, self-identity, self-esteem), which guide their internal dialogues, emotional reactions to situations, and the way they act on their world, interact with others, and perform in their sport

- The way they think and how this influences them both off and on the field (e.g., optimistic or pessimistic, critical or accepting, analytical or intuitive)

- Their emotional life, including their sensitivity, expressiveness, lability, and emotional reactions to setbacks and failure

- Their behavior in sport and nonsport settings

- The quality of their relationships and the way they interact with others (e.g., with empathy, support, divisiveness, or aggressiveness)

How Clients UnderstandThemselves

Self-knowledge on the part of athletes is an essential piece of the sport performance puzzle. Yet, the mental can lag behind the physical and technical facets of sport performance in terms of the athlete's appreciation, understanding, and development. Perhaps the most fundamental reason for this is that the physical and technical aspects of sport are readily observable and measurable. For example, if athletes want to determine their cardiovascular fitness, they can take a ![]() O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

In contrast, the mental side of sport is quite ethereal; it can't be seen, touched, or measured directly. Also, whereas the physical and technical elements of sport are highly objective, the mental components are very subjective. From the outside, we can only indirectly measure an athlete's psychology. From the inside, athletes don't always have great insight into the psychological and emotional machinations that occur between their ears. In a sense, assessment can enable athletes to build a better relationship with themselves by helping them understand what makes them tick.

Assessment can be a powerful tool for helping athletes plumb the depths of their psyches both on and off the field. All assessment tools, whether interviews, mental status exams, personality tests, sport-specific inventories, or psychophysiological measures, can help athletes understand their mental strengths and areas in need of improvement. This understanding can be valuable in several ways. Most obviously, assessment can clarify what areas athletes need to work on in their mental training. At a more basic level, effective assessment and the understanding it provides can explain to athletes why they do what they do mentally, such as why they get nervous before competitions or why they become frustrated when they can't readily learn a new technique. These realizations are often accompanied by the statement, "Now I know why I react that way!" From this epiphany and the greater understanding that psychological assessment provides, athletes gain the impetus and means to improve their strengths and alleviate their mental shortcomings.

How Clients Understand You

Assessment isn't just a unidirectional collecting of information in which you gather data about your client. Rather, it is a valuable tool for developing and strengthening the burgeoning relationship between you and your client. Assessment is a powerful way to begin building the connection, rapport, and trust that are so important for establishing an effective and comfortable professional relationship.

The assessments you use and the ways in which you collect information about your clients tells them a great deal about who you are as a person and as a professional. It is an opportunity for you to demonstrate appreciation for why your clients come to you. You can use assessments as a means of expressing concern and empathy for the difficulties that brought your clients to you. Assessment can also send the powerful message to clients that you understand them, and that understanding can act as the foundation for their belief that you can help them.

The assessment tools you use also educate clients about your areas of expertise, such as whether you focus on mental skills or administer psychophysiological protocols. Additionally, your choice of assessments reveals the mental areas that you believe are most important to athletic performance, such as motivation, confidence, focus, or mental imagery, and it communicates those areas that you intuit are at the heart of your clients' performance challenges, such as perfectionism or fear of failure. The assessments you select for clients give them their first hint at the intervention tools you may use (e.g., mental imagery, goal setting, cognitive restructuring) and how you may help the clients overcome their mental obstacles to achieve their athletic goals.

How Clients Understand Sport Psychology

As students or professionals in sport psychology, we have a clear and sophisticated understanding of what it is and how it can benefit athletes. However, clients who come to us for assistance related to the mental aspects of sport don't have this perspective. For many athletes, sport psychology is an amorphous concept; they only hold a vague sense that their mind is getting in the way of achieving their competitive goals. Yes, they know that the mental side of sport is important to athletic performance and success. At the same time, many would be hard pressed to provide an extensive accounting of what sport psychology entails, specific examples of mental factors that affect their performance, or mental skills they might use to improve their performance.

During the assessment, you evaluate your clients on many areas that are common to mental training programs offered by sport psychologists and mental coaches, including motivation, confidence, anxiety, focus, and mental imagery, as well as other performance-relevant areas such as perfectionism, fear of failure, and stress. As a consequence, assessment can provide clients with the opportunity to gain a better understanding of sport psychology, its components, its impact on their performance, and how it may benefit them. You are not only gaining a better understanding of your clients, but they are also learning more about all aspects of sport psychology. Thus, the assessment not only informs you about your clients and how best to assist them, but it is also provides them with an introduction to the field.

Save

Save

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

SRC Consultation Essentials

A critical first step in concussion management is accurate detection and diagnosis. Among several diagnostic schema for SRCs, the most comprehensive currently accepted diagnostic criteria were formulated in the consensus statement from the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, generally referred to as the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013).

A critical first step in concussion management is accurate detection and diagnosis. Among several diagnostic schema for SRCs, the most comprehensive currently accepted diagnostic criteria were formulated in the consensus statement from the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, generally referred to as the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013). According to this document, "Concussion is a brain injury and is defined as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by biomechanical forces" (p. 250). The statement further elaborates that the force may be from a direct blow to the head or may come from physical forces elsewhere on the body transmitted to the head; that the concussion results in time-limited neurologic impairment (although there may be a longer time course); that the immediate symptoms are due to a functional neurometabolic process rather than a structural injury that can be imaged using traditional neuroimaging techniques; and that concussion symptoms have a typical clinical presentation and should resolve in a typical sequential course. A majority of single, uncomplicated concussions resolve within 7 to 10 days; however, a longer recovery time may be needed in children and adolescents(McCrory et al., 2013).

SRC Symptoms and Course of Recovery

As shown in table 14.1, SRC symptoms are grouped into four clusters: physical, cognitive, emotional, and sleep.

Though a majority of collegiate and professional athletes with single, uncomplicated SRCs recover within 7 to 10 days, emerging data from a multiclinical assessment approach suggest it often takes three to four weeks for a complete recovery, especially for younger athletes (Henry, Elbin, Collins, Marchetti, & Kontos, 2015). This parallels the work of McCrea and colleagues, which supports a longer period of physiologic vulnerability even after traditional post-SRC assessment suggests symptom resolution (Nelson, Janecek, & McCrea, 2013). Growing consensus suggests that SRCs are best managed within a comprehensive education, prevention, and management program based in a clinic, school, or team or league. This program should provide resources and information geared toward all stakeholders involved, including athletes, parents, coaches, teachers, consultants, and sports medicine professionals. As a consultant working with athletes with SRCs, you are likely mandated by your state law and professional organization to know the fundamentals of SRC injury to ensure you can play an active role in helping athletes receive the best possible care.

Concussion Education Resources

Several resources for concussion education are available to consultants. The CDC's Heads Up Concussion in Youth Sports website (www.cdc.gov/HeadsUp/youthsports) provides free downloadable educational handouts for players, coaches, sport officials, and parents. It is particularly suitable for K - 12 sport programs. Collegiate and professional sport organizations have specific SRC training programs for their health care personnel that are based on material from the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013). The NCAA program addresses the special needs of the collegiate student-athlete (www.ncaa.org/health-and-safety/concussion-guidelines). The NHL, the NFL, and Major League Soccer (MLS) use a neuropsychological concussion evaluation model (Lovell, 2006). Finally, many professional organizations have developed concussion guidelines for their disciplines, such as the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and NATA (Echemendia, Giza, & Kutcher, 2015). Of these guidelines, the NATA position statement is one of the most comprehensive and pragmatic documents available. It is useful for all disciplines (Broglio et al., 2014), and therefore consultants working with concussed athletes should be familiar with it regardless of their discipline.

Components of SRC Assessment

With the preceding SRC education and management guidelines in mind, this section provides an overview of essential components of SRC assessment. Integrating data obtained from each assessment component during the postconcussion period is critical to maximize safe SRC recovery and expedite return to play (RTP) and return to learn (RTL) baseline assessment.

Preseason baseline neurocognitive assessment is essential, providing an individualized reference point for comparison in the event of an SRC, especially if the athlete has a preexisting academic learning disability, ADHD, or chronic medical or psychological condition. No athlete is perfect, and many have preexisting symptoms when not injured that can confound postinjury assessment and symptom management, necessitating the need for baseline assessment. Serial postinjury evaluations can be compared against the baseline to establish that an SRC has occurred, to quantify the initial degree of impairment and graduated improvement with rehabilitation and intervention, and to document final recovery. Some argue that this testing is too expensive to be practical and does not prevent concussions (Randolph, 2011); however, the consensus among sports medicine professionals is that it is essential when used within an integrated management program.

The Post-Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) is an established self-report tool for assessing preinjury baseline symptoms and for assessing and monitoring postinjury concussion symptoms (Pardini et al., 2004). When administered soon after SRC injury, PCSS scores can measure the extent of the injury compared with baseline functioning and may help predict which athletes may have a longer or more complicated recovery (Meehan, Mannix, Straccioloni, Elbin, & Collins, 2013). As with any psychometric instrument, education and training for using the PCSS instrument is necessary. The PCSS is widely used by both athletic trainers and consultants alike, provided that they have the education required to assess and monitor SRC injuries.

The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool-3 (SCAT3; McCrory et al., 2013) is another useful comprehensive instrument that can be administered both at baseline and field-side after a suspected SRC injury by the sports medicine professional responsible for immediate postinjury care. It assesses levels of consciousness, learning and memory, orientation, balance, range of motion, and coordination. A child version of the SCAT3 is available for athletes aged 5 to 12 years. The NHL has used the X2 iPad app version of the SCAT3 for baseline assessment. Due to the complexity of this instrument, advanced training in assessment and interpretation may be needed. However, athletic trainers, physicians, and psychologists with appropriate training can administer the SCAT3. If the consultant responsible for immediate care does not have such training, it is recommended that you use the Sport Concussion Recognition Tool, which relies more on observation of the athlete and a brief game-specific memory questionnaire (McCrory et al., 2013).

Administration of computerized neurocognitive assessment at preinjury baseline is a well-established protocol for assessing large numbers of athletes at one time (e.g., team level). However, although computerized assessment offers ease of administration, concerns remain about reliable and valid psychometrics and valid data interpretation. Appropriate personnel can supervise administration of computerized testing, but test results must be interpreted by consultants with appropriate training in psychometric theory and concussion management. It is recommended that neuropsychologists provide such test interpretation or be available for consultation (Echemendia et al., 2013). Two commonly used computerized instruments for SRC assessment include ImPACT(ImPACT Applications, 2015) and Cogstate CCAT. Core neurocognitive functions assessed by computer programs include attention, reaction time and processing speed, and memory. Scores are compared against general athletic groups. Postinjury reevaluation with the computerized instrument used at baseline can identify specific neurocognitive concussion sequelae and help track the course of recovery from the SRC. The computer program chosen should provide statistics indicating if the change in performance is truly significant and greater than changes due to practice effects, and it should have sound psychometrics that support the statistical reliability and validity of the instrument. Otherwise, the obtained results could be inaccurate (Alsalaheen, Stockdale, Pechumer, & Broglio, 2015; Nelson et al., 2016).

In summary, assessment tools used at baseline assist in establishing critical preinjury baseline functioning and preexisting symptoms necessary for comparison when assessing the presence and extent of postinjury concussion. Assessing a concussed athlete without an appropriate preinjury baseline can be done, but results must be interpreted with greater caution.

Assessment in Action

Using the PCSS in a Guided Interview Format

Consultants should complete this assessment tool in an interview format with concussed clients to better understand their SRC experience. The athlete rates each current SRC symptom on a scale from 0 to 6, and the consultant's interview elucidates activity and setting triggers and patterns in symptom clusters while encouraging the athlete to identify coping behaviors that reduce symptoms. Though only the PCSS total symptom score reliably predicts symptoms lasting longer than 28 days postinjury (Meehan et al., 2013), this recommended approach provides the consultant with valuable information for tailoring interventions and making appropriate, timely referrals to speed up SRC recovery.

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

Visual Assessment

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another.

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another. An athlete's ability to track objects and react appropriately develops with experience and at an individualized pace. Visual attention, perceptual information processing, and response selection can be disrupted by anxiety and distraction. Training to improve the allocation of attentional resources can enhance the development of these skills and protect them against the effects of pressure (Vine, Moore, & Wilson, 2014).

Benefits of Visual Search Assessment

Effective use of visual gaze behaviors (see table 10.2) and, in turn, the assessment of perceptual-cognitive skills, provides the following benefits:

- Anticipation: Looking at the right spot at the right time and making sense of what is seen enhances the ability to predict future events (Farrow & Abernathy, 2002; Savelsbergh, Williams, van der Kamp, & Ward, 2002).

- Attention: Efficient use of attentional resources involves focusing on the most important cues while ignoring distractions to take in the minimum amount of essential information. This results in the most efficient processing (Williams & Davids, 1998).

- Memory:Synthesis of past events into meaningful chunks of information enables athletes to employ effective strategies and tactics (Abernathy, Baker, & Cote, 2005).

- Pattern recognition:The ability to read plays based on experience (North & Williams, 2008) allows athletes to synthesize patterns and learn from them.

- Problem solving: The ability to conceptually organize thoughts based on visual information processing influences athletes' ability to determine what has worked and what hasn't (McPherson & Kernodle, 2003).

- Decision making: Athletes with effective perceptual-cognitive skills can read, anticipate, and make accurate decisions quickly (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, Mazyn, & Philippaerts, 2007).

- Situational awareness: The ability to perceive and understand the environment (Caserta & Abrams, 2007) improves as athletes know what is visually important and what to ignore.

- Motor efficiency: The result of effective perception and cognition in sport is often motor efficiency (Williams & Ericsson, 2007).

- Stress reduction: A further benefit of effective perceptual-cognitive skills is reduced stress (Gerstenberg, 2012). Being more focused and reducing information processing can lead to a cascading reduction in stress (Vickers & Lewinski, 2012).

- Alertness and resilience: The ability to stay alert over time is an important benefit of perceptual-cognitive skills. In any situation with a potential for fatigue, the more efficient the perceptions, cognitions, and motor responses, the greater the alertness and resilience (Williams, Hodges, North, & Barton, 2006).

Eye Tracking

Unlike biomechanical changes, which are readily observable, visual and cognitive processes are not so easily scrutinized. An eye tracker is a special pair of glasses that records athletes' point of gaze upon the environment, taking pictures of the location of the gaze at various frame rates (e.g., 60 times per second), similar to a camera. Eye-tracking technology enables us to make three types of visual feedback assessments.

Gaze Location

An eye tracker examines the location of a person's focal vision (gaze point) within an environment to determine if the subject is attending to the appropriate cues (see figure 10.4). For example, research has demonstrated that looking at the contact point when returning a serve in tennis assists in ball tracking (Murray & Hunfalvay, 2016). In baseball, the pitcher's hand positioning on the ball helps hitters determine the type of pitch that will be thrown (Takeuchi & Inomata, 2009).

(a) Minor League Baseball aggregate visual search cues versus (b) Major League Baseball aggregate visual search cues. Major leaguers demonstrate attention to fewer and more localized visual cues.

Assessment of visual feedback gaze location using eye trackers is based on research using temporal occlusion (Farrow, Abernathy, & Jackson, 2005), where the task being viewed is stopped at various points before completion and athletes are asked to extrapolate information about what will happen in the future, such as the direction a ball will travel. Visual feedback is also based on cue occlusion (also called spatial occlusion) research (Muller & Abernathy, 2006), where important cues are blocked from view to determine their impact on performance. These assessment paradigms measure performance outcomes using additional tools such as pressure-sensitive floor mats and infrared beams that detect response time (Williams & Ericsson, 2005).

Common assessments of gaze error include missed cues, scattered visual search, and late tracking. Missed cues (see figure 10.5) are often caused by a lack of perceptual-cognitive expertise or a failure to understand what the cue reveals, why it is important, and how it can be used to improve performance.

Gaze location and important visual cues. Solid circles represent important visual cues. Dotted circles represent the athlete's actual gaze location. Convergence of the two is scored out of a possible 100. Here, the missed cue in the toss phase results in failure to target the contact point and late ball tracking.

A second common error in gaze location is a scattered visual search pattern. Figure 10.4a demonstrates the wider visual search area of a less experienced baseball player. Research demonstrates that experts exhibit fewer fixations of longer duration compared with less skilled performers (Gegenfurtner, Lehtinen, & Säljö, 2011; Mann, Ward, Williams, & Janelle, 2007). Less skilled athletes who display a scattered search pattern end up processing too many cues because they are unsure where to look and what is important.

Late tracking is another common error in gaze location. This occurs especially in fast-moving, open-skilled sports when athletes start late and do not have time to catch up. This can be due to a lack of expertise or a lack of attention or readiness. Late tracking in the beginning of a sequence has negative consequences that multiply further along the biomechanical phases.

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

Purpose of Assessment

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people.

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people. Assessment also tells clients a great deal about who you are and how you work and about your field more broadly.

Understanding the Person as an Athlete

The most obvious part of understanding involves the person as an athlete - that is, what makes her tick in training and competition. This understanding involves a wide range of psychology, including how athletes think, the emotions they experience, and the way they behave, particularly in the heat of competition. Specific components of athletes' psychology consist of their attitudes toward and relationships with success, failure, expectations, and competition. Mental factors that must be understood include motivation, confidence, intensity (e.g., energy, arousal, anxiety), focus, and emotions. Athletes' psychology can also include the mental tools athletes use in their preparation and performance, such as goal setting, mental imagery, routines, self-talk, and breathing. Furthermore, it can include their relationships with teammates, coaches, competitors, officials, and, importantly for young athletes, parents.

Even though consultants may be focusing on athletes' psychology, a true understanding of athletes must also include every area that affects performance, such as physical conditioning, technique, tactics, equipment, and team dynamics. Consultants need to know athletes' strengths and weaknesses in these areas, as well as how they approach their training and competitive performances.

Understanding the Athlete as a Person

In sport psychology there may be a tendency to view clients as athletes alone, forgetting that they are first and foremost people. For example, when athletes enter the field of competition, they don't leave their personness, so to speak, on the sidelines. Whoever they are as people will be expressed on the field as they pursue their athletic goals. Whatever weaknesses they hold as people, such as doubts, worries, or fears, will come out in their athletic performance. In a more positive light, whatever strengths they possess as people - whether determination, confidence, or resilience - will also emerge in practice and competition.

Just thinking about exploring the depth and breadth of a client's internal athletic life, much less her personal psyche, can be a daunting task. The athlete as person encompasses every aspect of who athletes are:

- Their innate dispositions, temperament, and tendencies (e.g., introverted or extroverted, stoic or emotional)

- Their values and priorities that act as signposts for their aspirations and goals

- Their beliefs about themselves (e.g., self-assessment, self-identity, self-esteem), which guide their internal dialogues, emotional reactions to situations, and the way they act on their world, interact with others, and perform in their sport

- The way they think and how this influences them both off and on the field (e.g., optimistic or pessimistic, critical or accepting, analytical or intuitive)

- Their emotional life, including their sensitivity, expressiveness, lability, and emotional reactions to setbacks and failure

- Their behavior in sport and nonsport settings

- The quality of their relationships and the way they interact with others (e.g., with empathy, support, divisiveness, or aggressiveness)

How Clients UnderstandThemselves

Self-knowledge on the part of athletes is an essential piece of the sport performance puzzle. Yet, the mental can lag behind the physical and technical facets of sport performance in terms of the athlete's appreciation, understanding, and development. Perhaps the most fundamental reason for this is that the physical and technical aspects of sport are readily observable and measurable. For example, if athletes want to determine their cardiovascular fitness, they can take a ![]() O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

In contrast, the mental side of sport is quite ethereal; it can't be seen, touched, or measured directly. Also, whereas the physical and technical elements of sport are highly objective, the mental components are very subjective. From the outside, we can only indirectly measure an athlete's psychology. From the inside, athletes don't always have great insight into the psychological and emotional machinations that occur between their ears. In a sense, assessment can enable athletes to build a better relationship with themselves by helping them understand what makes them tick.

Assessment can be a powerful tool for helping athletes plumb the depths of their psyches both on and off the field. All assessment tools, whether interviews, mental status exams, personality tests, sport-specific inventories, or psychophysiological measures, can help athletes understand their mental strengths and areas in need of improvement. This understanding can be valuable in several ways. Most obviously, assessment can clarify what areas athletes need to work on in their mental training. At a more basic level, effective assessment and the understanding it provides can explain to athletes why they do what they do mentally, such as why they get nervous before competitions or why they become frustrated when they can't readily learn a new technique. These realizations are often accompanied by the statement, "Now I know why I react that way!" From this epiphany and the greater understanding that psychological assessment provides, athletes gain the impetus and means to improve their strengths and alleviate their mental shortcomings.

How Clients Understand You

Assessment isn't just a unidirectional collecting of information in which you gather data about your client. Rather, it is a valuable tool for developing and strengthening the burgeoning relationship between you and your client. Assessment is a powerful way to begin building the connection, rapport, and trust that are so important for establishing an effective and comfortable professional relationship.

The assessments you use and the ways in which you collect information about your clients tells them a great deal about who you are as a person and as a professional. It is an opportunity for you to demonstrate appreciation for why your clients come to you. You can use assessments as a means of expressing concern and empathy for the difficulties that brought your clients to you. Assessment can also send the powerful message to clients that you understand them, and that understanding can act as the foundation for their belief that you can help them.

The assessment tools you use also educate clients about your areas of expertise, such as whether you focus on mental skills or administer psychophysiological protocols. Additionally, your choice of assessments reveals the mental areas that you believe are most important to athletic performance, such as motivation, confidence, focus, or mental imagery, and it communicates those areas that you intuit are at the heart of your clients' performance challenges, such as perfectionism or fear of failure. The assessments you select for clients give them their first hint at the intervention tools you may use (e.g., mental imagery, goal setting, cognitive restructuring) and how you may help the clients overcome their mental obstacles to achieve their athletic goals.

How Clients Understand Sport Psychology

As students or professionals in sport psychology, we have a clear and sophisticated understanding of what it is and how it can benefit athletes. However, clients who come to us for assistance related to the mental aspects of sport don't have this perspective. For many athletes, sport psychology is an amorphous concept; they only hold a vague sense that their mind is getting in the way of achieving their competitive goals. Yes, they know that the mental side of sport is important to athletic performance and success. At the same time, many would be hard pressed to provide an extensive accounting of what sport psychology entails, specific examples of mental factors that affect their performance, or mental skills they might use to improve their performance.

During the assessment, you evaluate your clients on many areas that are common to mental training programs offered by sport psychologists and mental coaches, including motivation, confidence, anxiety, focus, and mental imagery, as well as other performance-relevant areas such as perfectionism, fear of failure, and stress. As a consequence, assessment can provide clients with the opportunity to gain a better understanding of sport psychology, its components, its impact on their performance, and how it may benefit them. You are not only gaining a better understanding of your clients, but they are also learning more about all aspects of sport psychology. Thus, the assessment not only informs you about your clients and how best to assist them, but it is also provides them with an introduction to the field.

Save

Save

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

SRC Consultation Essentials

A critical first step in concussion management is accurate detection and diagnosis. Among several diagnostic schema for SRCs, the most comprehensive currently accepted diagnostic criteria were formulated in the consensus statement from the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, generally referred to as the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013).

A critical first step in concussion management is accurate detection and diagnosis. Among several diagnostic schema for SRCs, the most comprehensive currently accepted diagnostic criteria were formulated in the consensus statement from the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, generally referred to as the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013). According to this document, "Concussion is a brain injury and is defined as a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by biomechanical forces" (p. 250). The statement further elaborates that the force may be from a direct blow to the head or may come from physical forces elsewhere on the body transmitted to the head; that the concussion results in time-limited neurologic impairment (although there may be a longer time course); that the immediate symptoms are due to a functional neurometabolic process rather than a structural injury that can be imaged using traditional neuroimaging techniques; and that concussion symptoms have a typical clinical presentation and should resolve in a typical sequential course. A majority of single, uncomplicated concussions resolve within 7 to 10 days; however, a longer recovery time may be needed in children and adolescents(McCrory et al., 2013).

SRC Symptoms and Course of Recovery

As shown in table 14.1, SRC symptoms are grouped into four clusters: physical, cognitive, emotional, and sleep.

Though a majority of collegiate and professional athletes with single, uncomplicated SRCs recover within 7 to 10 days, emerging data from a multiclinical assessment approach suggest it often takes three to four weeks for a complete recovery, especially for younger athletes (Henry, Elbin, Collins, Marchetti, & Kontos, 2015). This parallels the work of McCrea and colleagues, which supports a longer period of physiologic vulnerability even after traditional post-SRC assessment suggests symptom resolution (Nelson, Janecek, & McCrea, 2013). Growing consensus suggests that SRCs are best managed within a comprehensive education, prevention, and management program based in a clinic, school, or team or league. This program should provide resources and information geared toward all stakeholders involved, including athletes, parents, coaches, teachers, consultants, and sports medicine professionals. As a consultant working with athletes with SRCs, you are likely mandated by your state law and professional organization to know the fundamentals of SRC injury to ensure you can play an active role in helping athletes receive the best possible care.

Concussion Education Resources

Several resources for concussion education are available to consultants. The CDC's Heads Up Concussion in Youth Sports website (www.cdc.gov/HeadsUp/youthsports) provides free downloadable educational handouts for players, coaches, sport officials, and parents. It is particularly suitable for K - 12 sport programs. Collegiate and professional sport organizations have specific SRC training programs for their health care personnel that are based on material from the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013). The NCAA program addresses the special needs of the collegiate student-athlete (www.ncaa.org/health-and-safety/concussion-guidelines). The NHL, the NFL, and Major League Soccer (MLS) use a neuropsychological concussion evaluation model (Lovell, 2006). Finally, many professional organizations have developed concussion guidelines for their disciplines, such as the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and NATA (Echemendia, Giza, & Kutcher, 2015). Of these guidelines, the NATA position statement is one of the most comprehensive and pragmatic documents available. It is useful for all disciplines (Broglio et al., 2014), and therefore consultants working with concussed athletes should be familiar with it regardless of their discipline.

Components of SRC Assessment

With the preceding SRC education and management guidelines in mind, this section provides an overview of essential components of SRC assessment. Integrating data obtained from each assessment component during the postconcussion period is critical to maximize safe SRC recovery and expedite return to play (RTP) and return to learn (RTL) baseline assessment.

Preseason baseline neurocognitive assessment is essential, providing an individualized reference point for comparison in the event of an SRC, especially if the athlete has a preexisting academic learning disability, ADHD, or chronic medical or psychological condition. No athlete is perfect, and many have preexisting symptoms when not injured that can confound postinjury assessment and symptom management, necessitating the need for baseline assessment. Serial postinjury evaluations can be compared against the baseline to establish that an SRC has occurred, to quantify the initial degree of impairment and graduated improvement with rehabilitation and intervention, and to document final recovery. Some argue that this testing is too expensive to be practical and does not prevent concussions (Randolph, 2011); however, the consensus among sports medicine professionals is that it is essential when used within an integrated management program.

The Post-Concussion Symptom Scale (PCSS) is an established self-report tool for assessing preinjury baseline symptoms and for assessing and monitoring postinjury concussion symptoms (Pardini et al., 2004). When administered soon after SRC injury, PCSS scores can measure the extent of the injury compared with baseline functioning and may help predict which athletes may have a longer or more complicated recovery (Meehan, Mannix, Straccioloni, Elbin, & Collins, 2013). As with any psychometric instrument, education and training for using the PCSS instrument is necessary. The PCSS is widely used by both athletic trainers and consultants alike, provided that they have the education required to assess and monitor SRC injuries.

The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool-3 (SCAT3; McCrory et al., 2013) is another useful comprehensive instrument that can be administered both at baseline and field-side after a suspected SRC injury by the sports medicine professional responsible for immediate postinjury care. It assesses levels of consciousness, learning and memory, orientation, balance, range of motion, and coordination. A child version of the SCAT3 is available for athletes aged 5 to 12 years. The NHL has used the X2 iPad app version of the SCAT3 for baseline assessment. Due to the complexity of this instrument, advanced training in assessment and interpretation may be needed. However, athletic trainers, physicians, and psychologists with appropriate training can administer the SCAT3. If the consultant responsible for immediate care does not have such training, it is recommended that you use the Sport Concussion Recognition Tool, which relies more on observation of the athlete and a brief game-specific memory questionnaire (McCrory et al., 2013).

Administration of computerized neurocognitive assessment at preinjury baseline is a well-established protocol for assessing large numbers of athletes at one time (e.g., team level). However, although computerized assessment offers ease of administration, concerns remain about reliable and valid psychometrics and valid data interpretation. Appropriate personnel can supervise administration of computerized testing, but test results must be interpreted by consultants with appropriate training in psychometric theory and concussion management. It is recommended that neuropsychologists provide such test interpretation or be available for consultation (Echemendia et al., 2013). Two commonly used computerized instruments for SRC assessment include ImPACT(ImPACT Applications, 2015) and Cogstate CCAT. Core neurocognitive functions assessed by computer programs include attention, reaction time and processing speed, and memory. Scores are compared against general athletic groups. Postinjury reevaluation with the computerized instrument used at baseline can identify specific neurocognitive concussion sequelae and help track the course of recovery from the SRC. The computer program chosen should provide statistics indicating if the change in performance is truly significant and greater than changes due to practice effects, and it should have sound psychometrics that support the statistical reliability and validity of the instrument. Otherwise, the obtained results could be inaccurate (Alsalaheen, Stockdale, Pechumer, & Broglio, 2015; Nelson et al., 2016).

In summary, assessment tools used at baseline assist in establishing critical preinjury baseline functioning and preexisting symptoms necessary for comparison when assessing the presence and extent of postinjury concussion. Assessing a concussed athlete without an appropriate preinjury baseline can be done, but results must be interpreted with greater caution.

Assessment in Action

Using the PCSS in a Guided Interview Format

Consultants should complete this assessment tool in an interview format with concussed clients to better understand their SRC experience. The athlete rates each current SRC symptom on a scale from 0 to 6, and the consultant's interview elucidates activity and setting triggers and patterns in symptom clusters while encouraging the athlete to identify coping behaviors that reduce symptoms. Though only the PCSS total symptom score reliably predicts symptoms lasting longer than 28 days postinjury (Meehan et al., 2013), this recommended approach provides the consultant with valuable information for tailoring interventions and making appropriate, timely referrals to speed up SRC recovery.

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

Visual Assessment

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another.

The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another. An athlete's ability to track objects and react appropriately develops with experience and at an individualized pace. Visual attention, perceptual information processing, and response selection can be disrupted by anxiety and distraction. Training to improve the allocation of attentional resources can enhance the development of these skills and protect them against the effects of pressure (Vine, Moore, & Wilson, 2014).

Benefits of Visual Search Assessment

Effective use of visual gaze behaviors (see table 10.2) and, in turn, the assessment of perceptual-cognitive skills, provides the following benefits:

- Anticipation: Looking at the right spot at the right time and making sense of what is seen enhances the ability to predict future events (Farrow & Abernathy, 2002; Savelsbergh, Williams, van der Kamp, & Ward, 2002).

- Attention: Efficient use of attentional resources involves focusing on the most important cues while ignoring distractions to take in the minimum amount of essential information. This results in the most efficient processing (Williams & Davids, 1998).

- Memory:Synthesis of past events into meaningful chunks of information enables athletes to employ effective strategies and tactics (Abernathy, Baker, & Cote, 2005).

- Pattern recognition:The ability to read plays based on experience (North & Williams, 2008) allows athletes to synthesize patterns and learn from them.

- Problem solving: The ability to conceptually organize thoughts based on visual information processing influences athletes' ability to determine what has worked and what hasn't (McPherson & Kernodle, 2003).

- Decision making: Athletes with effective perceptual-cognitive skills can read, anticipate, and make accurate decisions quickly (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, Mazyn, & Philippaerts, 2007).

- Situational awareness: The ability to perceive and understand the environment (Caserta & Abrams, 2007) improves as athletes know what is visually important and what to ignore.

- Motor efficiency: The result of effective perception and cognition in sport is often motor efficiency (Williams & Ericsson, 2007).

- Stress reduction: A further benefit of effective perceptual-cognitive skills is reduced stress (Gerstenberg, 2012). Being more focused and reducing information processing can lead to a cascading reduction in stress (Vickers & Lewinski, 2012).

- Alertness and resilience: The ability to stay alert over time is an important benefit of perceptual-cognitive skills. In any situation with a potential for fatigue, the more efficient the perceptions, cognitions, and motor responses, the greater the alertness and resilience (Williams, Hodges, North, & Barton, 2006).

Eye Tracking

Unlike biomechanical changes, which are readily observable, visual and cognitive processes are not so easily scrutinized. An eye tracker is a special pair of glasses that records athletes' point of gaze upon the environment, taking pictures of the location of the gaze at various frame rates (e.g., 60 times per second), similar to a camera. Eye-tracking technology enables us to make three types of visual feedback assessments.

Gaze Location

An eye tracker examines the location of a person's focal vision (gaze point) within an environment to determine if the subject is attending to the appropriate cues (see figure 10.4). For example, research has demonstrated that looking at the contact point when returning a serve in tennis assists in ball tracking (Murray & Hunfalvay, 2016). In baseball, the pitcher's hand positioning on the ball helps hitters determine the type of pitch that will be thrown (Takeuchi & Inomata, 2009).

(a) Minor League Baseball aggregate visual search cues versus (b) Major League Baseball aggregate visual search cues. Major leaguers demonstrate attention to fewer and more localized visual cues.

Assessment of visual feedback gaze location using eye trackers is based on research using temporal occlusion (Farrow, Abernathy, & Jackson, 2005), where the task being viewed is stopped at various points before completion and athletes are asked to extrapolate information about what will happen in the future, such as the direction a ball will travel. Visual feedback is also based on cue occlusion (also called spatial occlusion) research (Muller & Abernathy, 2006), where important cues are blocked from view to determine their impact on performance. These assessment paradigms measure performance outcomes using additional tools such as pressure-sensitive floor mats and infrared beams that detect response time (Williams & Ericsson, 2005).

Common assessments of gaze error include missed cues, scattered visual search, and late tracking. Missed cues (see figure 10.5) are often caused by a lack of perceptual-cognitive expertise or a failure to understand what the cue reveals, why it is important, and how it can be used to improve performance.

Gaze location and important visual cues. Solid circles represent important visual cues. Dotted circles represent the athlete's actual gaze location. Convergence of the two is scored out of a possible 100. Here, the missed cue in the toss phase results in failure to target the contact point and late ball tracking.

A second common error in gaze location is a scattered visual search pattern. Figure 10.4a demonstrates the wider visual search area of a less experienced baseball player. Research demonstrates that experts exhibit fewer fixations of longer duration compared with less skilled performers (Gegenfurtner, Lehtinen, & Säljö, 2011; Mann, Ward, Williams, & Janelle, 2007). Less skilled athletes who display a scattered search pattern end up processing too many cues because they are unsure where to look and what is important.

Late tracking is another common error in gaze location. This occurs especially in fast-moving, open-skilled sports when athletes start late and do not have time to catch up. This can be due to a lack of expertise or a lack of attention or readiness. Late tracking in the beginning of a sequence has negative consequences that multiply further along the biomechanical phases.

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

Purpose of Assessment

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people.

To understand your athletes, you need a comprehensive knowledge of all aspects of the athletes that will affect their performance. This broad understanding involves who they are as athletes and, just as importantly, who they are as people. Assessment also tells clients a great deal about who you are and how you work and about your field more broadly.

Understanding the Person as an Athlete

The most obvious part of understanding involves the person as an athlete - that is, what makes her tick in training and competition. This understanding involves a wide range of psychology, including how athletes think, the emotions they experience, and the way they behave, particularly in the heat of competition. Specific components of athletes' psychology consist of their attitudes toward and relationships with success, failure, expectations, and competition. Mental factors that must be understood include motivation, confidence, intensity (e.g., energy, arousal, anxiety), focus, and emotions. Athletes' psychology can also include the mental tools athletes use in their preparation and performance, such as goal setting, mental imagery, routines, self-talk, and breathing. Furthermore, it can include their relationships with teammates, coaches, competitors, officials, and, importantly for young athletes, parents.

Even though consultants may be focusing on athletes' psychology, a true understanding of athletes must also include every area that affects performance, such as physical conditioning, technique, tactics, equipment, and team dynamics. Consultants need to know athletes' strengths and weaknesses in these areas, as well as how they approach their training and competitive performances.

Understanding the Athlete as a Person

In sport psychology there may be a tendency to view clients as athletes alone, forgetting that they are first and foremost people. For example, when athletes enter the field of competition, they don't leave their personness, so to speak, on the sidelines. Whoever they are as people will be expressed on the field as they pursue their athletic goals. Whatever weaknesses they hold as people, such as doubts, worries, or fears, will come out in their athletic performance. In a more positive light, whatever strengths they possess as people - whether determination, confidence, or resilience - will also emerge in practice and competition.

Just thinking about exploring the depth and breadth of a client's internal athletic life, much less her personal psyche, can be a daunting task. The athlete as person encompasses every aspect of who athletes are:

- Their innate dispositions, temperament, and tendencies (e.g., introverted or extroverted, stoic or emotional)

- Their values and priorities that act as signposts for their aspirations and goals

- Their beliefs about themselves (e.g., self-assessment, self-identity, self-esteem), which guide their internal dialogues, emotional reactions to situations, and the way they act on their world, interact with others, and perform in their sport

- The way they think and how this influences them both off and on the field (e.g., optimistic or pessimistic, critical or accepting, analytical or intuitive)

- Their emotional life, including their sensitivity, expressiveness, lability, and emotional reactions to setbacks and failure

- Their behavior in sport and nonsport settings

- The quality of their relationships and the way they interact with others (e.g., with empathy, support, divisiveness, or aggressiveness)

How Clients UnderstandThemselves

Self-knowledge on the part of athletes is an essential piece of the sport performance puzzle. Yet, the mental can lag behind the physical and technical facets of sport performance in terms of the athlete's appreciation, understanding, and development. Perhaps the most fundamental reason for this is that the physical and technical aspects of sport are readily observable and measurable. For example, if athletes want to determine their cardiovascular fitness, they can take a ![]() O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

O2max test. If they want to be evaluated technically, they can watch themselves on video or participate in biomechanical testing.

In contrast, the mental side of sport is quite ethereal; it can't be seen, touched, or measured directly. Also, whereas the physical and technical elements of sport are highly objective, the mental components are very subjective. From the outside, we can only indirectly measure an athlete's psychology. From the inside, athletes don't always have great insight into the psychological and emotional machinations that occur between their ears. In a sense, assessment can enable athletes to build a better relationship with themselves by helping them understand what makes them tick.

Assessment can be a powerful tool for helping athletes plumb the depths of their psyches both on and off the field. All assessment tools, whether interviews, mental status exams, personality tests, sport-specific inventories, or psychophysiological measures, can help athletes understand their mental strengths and areas in need of improvement. This understanding can be valuable in several ways. Most obviously, assessment can clarify what areas athletes need to work on in their mental training. At a more basic level, effective assessment and the understanding it provides can explain to athletes why they do what they do mentally, such as why they get nervous before competitions or why they become frustrated when they can't readily learn a new technique. These realizations are often accompanied by the statement, "Now I know why I react that way!" From this epiphany and the greater understanding that psychological assessment provides, athletes gain the impetus and means to improve their strengths and alleviate their mental shortcomings.

How Clients Understand You

Assessment isn't just a unidirectional collecting of information in which you gather data about your client. Rather, it is a valuable tool for developing and strengthening the burgeoning relationship between you and your client. Assessment is a powerful way to begin building the connection, rapport, and trust that are so important for establishing an effective and comfortable professional relationship.

The assessments you use and the ways in which you collect information about your clients tells them a great deal about who you are as a person and as a professional. It is an opportunity for you to demonstrate appreciation for why your clients come to you. You can use assessments as a means of expressing concern and empathy for the difficulties that brought your clients to you. Assessment can also send the powerful message to clients that you understand them, and that understanding can act as the foundation for their belief that you can help them.

The assessment tools you use also educate clients about your areas of expertise, such as whether you focus on mental skills or administer psychophysiological protocols. Additionally, your choice of assessments reveals the mental areas that you believe are most important to athletic performance, such as motivation, confidence, focus, or mental imagery, and it communicates those areas that you intuit are at the heart of your clients' performance challenges, such as perfectionism or fear of failure. The assessments you select for clients give them their first hint at the intervention tools you may use (e.g., mental imagery, goal setting, cognitive restructuring) and how you may help the clients overcome their mental obstacles to achieve their athletic goals.

How Clients Understand Sport Psychology

As students or professionals in sport psychology, we have a clear and sophisticated understanding of what it is and how it can benefit athletes. However, clients who come to us for assistance related to the mental aspects of sport don't have this perspective. For many athletes, sport psychology is an amorphous concept; they only hold a vague sense that their mind is getting in the way of achieving their competitive goals. Yes, they know that the mental side of sport is important to athletic performance and success. At the same time, many would be hard pressed to provide an extensive accounting of what sport psychology entails, specific examples of mental factors that affect their performance, or mental skills they might use to improve their performance.

During the assessment, you evaluate your clients on many areas that are common to mental training programs offered by sport psychologists and mental coaches, including motivation, confidence, anxiety, focus, and mental imagery, as well as other performance-relevant areas such as perfectionism, fear of failure, and stress. As a consequence, assessment can provide clients with the opportunity to gain a better understanding of sport psychology, its components, its impact on their performance, and how it may benefit them. You are not only gaining a better understanding of your clients, but they are also learning more about all aspects of sport psychology. Thus, the assessment not only informs you about your clients and how best to assist them, but it is also provides them with an introduction to the field.

Save

Save

Learn more about Assessment in Applied Sport Psychology.

SRC Consultation Essentials

A critical first step in concussion management is accurate detection and diagnosis. Among several diagnostic schema for SRCs, the most comprehensive currently accepted diagnostic criteria were formulated in the consensus statement from the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, generally referred to as the Zurich Conference (McCrory et al., 2013).