- Home

- Physiology of Sport and Exercise

- Kinesiology/Exercise and Sport Science

- Biomechanics

- Exercise Biochemistry

Exercise Biochemistry

496 Pages

Exercise Biochemistry, Second Edition, takes a potentially difficult and technical subject and translates it into a clear explanation of how exercise affects molecular-level functioning in athletes and nonathletes, both healthy and diseased. Extremely student friendly, this text is written in conversational style by Vassilis Mougios, who poses and then answers questions as if having a dialogue with a student. Using simple language supported by ample analogies and numerous illustrations, he is able to drive home important concepts for students without compromising scientific accuracy and content.

With significantly updated research, the second edition of Exercise Biochemistry offers a complete compilation, from basic topics to more advanced topics. It includes coverage of metabolism, endocrinology, and assessment all in one volume. This edition also adds the following:

• A chapter on vitamins and minerals present in the human diet

• An evidence-based chapter on exercise and disease that shows how appropriate exercise prescriptions can mobilize biochemical mechanisms in the body to fight obesity, cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, cancer, osteoporosis, mental disease, and aging

• Updated information on nucleic acids and gene expression, including exercise genetics, RNA interference, and epigenetics

• An examination of caffeine as an ergogenic aid to better demonstrate the relationship between caffeine and fatigue

• Up-to-date findings on how different types of exercise affect lipid metabolism and the use of individual fatty acids during exercise

To facilitate student learning, Exercise Biochemistry incorporates chapter objectives and summaries, key terms, sidebars, and questions and problems posed at the end of each chapter. It leads students through four successive parts. Part I introduces biochemistry basics, including metabolism, proteins, nucleic acids and gene expression, carbohydrates and lipids, and vitamins and minerals. Part II applies the basics to explore neural control of movement and muscle activity. The essence of the book is found in part III, which details exercise metabolism related to carbohydrates, lipids, and protein; compounds of high phosphoryl-transfer potential; effects of exercise on gene expression; integration of exercise metabolism; and the use of exercise to fight disease. Part IV focuses on biochemical assessment of people who exercise, with chapters on iron status, metabolites, enzymes, and hormones. Simple biochemical assessments of health and performance are also discussed.

Exercise Biochemistry, Second Edition, is an authoritative resource that will arm future sport and exercise scientists with a clear understanding of the effects of exercise on the function of the human body.

Part I. Biochemistry Basics

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1 Chemical Elements

1.2 Chemical Bonds

1.3 Molecules

1.4 Ions

1.5 Radicals

1.6 Polarity Influences Miscibility

1.7 Solutions

1.8 Chemical Reactions

1.9 Chemical Equilibrium

1.10 pH

1.11 Acid-Base Interconversions

1.12 Buffer Systems

1.13 Classes of Biological Substances

1.14 Classes of Nutrients

1.15 Cell Structure

Chapter 2. Metabolism

2.1 Free-Energy Changes of Metabolic Reactions

2.2 Determinants of Free-Energy Change

2.3 ATP, the Energy Currency of Cells

2.4 Phases of Metabolism

2.5 Redox Reactions

2.6 Overview of Catabolism

Chapter 3. Proteins

3.1 Amino Acids

3.2 The Peptide Bond

3.3 Primary Structure of Proteins

3.4 Secondary Structure

3.5 Tertiary Structure

3.6 Denaturation

3.7 Quaternary Structure

3.8 Protein Function

3.9 Oxygen Carriers

3.10 Myoglobin

3.11 Hemoglobin Structure

3.12 The Wondrous Properties of Hemoglobin

3.13 Enzymes

3.14 The Active Site

3.15 How Enzymes Speed up Metabolic Reactions

3.16 Factors Affecting the Rate of Enzyme Reactions

Chapter 4. Nucleic Acids and Gene Expression

4.1 Introducing Nucleic Acids

4.2 Flow of Genetic Information

4.3 Deoxyribonucleotides, the Building Blocks of DNA

4.4 Primary Structure of DNA

4.5 The Double Helix of DNA

4.6 The Genome of Living Organisms

4.7 DNA Replication

4.8 Mutations

4.9 RNA

4.10 Transcription

4.11 Delimiting Transcription

4.12 Genes and Gene Expression

4.13 Messenger RNA

4.14 Translation

4.15 The Genetic Code

4.16 Transfer RNA

4.17 Translation Continued

4.18 In the Beginning, RNA?

Chapter 5. Carbohydrates and Lipids

5.1 Carbohydrates

5.2 Monosaccharides

5.3 Oligosaccharides

5.4 Polysaccharides

5.5 Carbohydrate Categories in Nutrition

5.6 Lipids

5.7 Fatty Acids

5.8 Triacylglycerols

5.9 Phospholipids

5.10 Steroids

5.11 Cell Membranes

Chapter 6. Vitamins and Minerals

6.1 Water Soluble Vitamins

6.2 Fat Soluble Vitamins

6.3 Metal Minerals

6.4 Nonmetal Minerals

6.5 Elements in the Human Body

Part II. Biochemistry of the Neural and Muscular Processes of Movement

Chapter 7. Neural Control of Movement

7.1 Two Ways of Transmission of Nerve Signals

7.2 The Resting Potential

7.3 The Action Potential

7.4 Propagation of an Action Potential

7.5 Transmission of a Nerve Impulse from One Neuron to Another

7.6 Birth of a Nerve Impulse

7.7 The Neuromuscular Junction

7.8 Changes in Motor Neuron Activity During Exercise

7.9 A Lethal Arsenal at the Service of Research

Chapter 8. Muscle Activity

8.1 Structure of a Muscle Cell

8.2 The Sliding-Filament Theory

8.3 The Wondrous Properties of Myosin

8.4 Myosin Structure

8.5 Actin

8.6 Sarcomere Architecture

8.7 Mechanism of Force Generation

8.8 Myosin Isoforms and Muscle Fiber Types

8.9 Control of Muscle Contraction by Ca2+

8.10 Excitation-Contraction Coupling

Part III. Exercise Metabolism

III.1 Principles of Exercise Metabolism

III.2 Exercise Parameters

III.3 Experimental Models Used to Study Exercise Metabolism

III.4 Five Means of Metabolic Control in Exercise

III.5 Four Classes of Energy Sources in Exercise

Chapter 9. Compounds of High Phosphoryl Transfer Potential

9.1 The ATP-ADP Cycle

9.2 The ATP-ADP Cycle in Exercise

9.3 Phosphocreatine

9.4 Watching Exercise Metabolism

9.5 Loss of AMP by Deamination

9.6 Purine Degradation

Chapter 10. Carbohydrate Metabolism in Exercise

10.1 Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption

10.2 Glycogen Content of the Human Body

10.3 Glycogenesis

10.4 Glycogenolysis

10.5 Exercise Speeds Up Glycogenolysis in Muscle

10.6 The Cyclic-AMP Cascade

10.7 Recapping the Effect of Exercise on Muscle Glycogen Metabolism

10.8 Glycolysis

10.9 Exercise Speeds Up Glycolysis in Muscle

10.10 Pyruvate Oxidation

10.11 Exercise Speeds Up Pyruvate Oxidation in Muscle

10.12 The Citric Acid Cycle

10.13 Exercise Speeds Up the Citric Acid Cycle in Muscle

10.14 The Electron Transport Chain

10.15 Oxidative Phosphorylation

10.16 Energy Yield of the Electron Transport Chain

10.17 Energy Yield of Carbohydrate Oxidation

10.18 Exercise Speeds Up Oxidative Phosphorylation in Muscle

10.19 Lactate Production in Muscle During Exercise

10.20 Is Lactate Production a Cause of Fatigue?

10.21 Is Lactate Production Due to a Lack of Oxygen?

10.22 Features of the Anaerobic Carbohydrate Catabolism

10.23 Utilizing Lactate

10.24 Gluconeogenesis

10.25 A Shortcut in Gluconeogenesis

10.26 Exercise Speeds Up Gluconeogenesis in the Liver

10.27 The Cori Cycle

10.28 Exercise Speeds Up Glycogenolysis in the Liver

10.29 Control of the Plasma Glucose Concentration in Exercise

10.30 Blood Lactate Accumulation

10.31 Blood Lactate Decline

10.32 “Thresholds”

Chapter 11. Lipid Metabolism in Exercise

11.1 Triacylglycerol Digestion, Absorption, and Distribution

11.2 Digestion, Absorption, and Distribution of Other Lipids

11.3 Fat Content of the Human Body

11.4 Triacylglycerol Synthesis in Adipose Tissue

11.5 Lipolysis

11.6 Exercise Speeds Up Lipolysis in Adipose Tissue

11.7 Exercise Speeds Up Lipolysis in Muscle

11.8 Fate of the Lipolytic Products During Exercise

11.9 Fatty Acid Degradation

11.10 Energy Yield of Fatty Acid Oxidation

11.11 Degradation of Unsaturated Fatty Acids

11.12 Degradation of Odd-Number Fatty Acids

11.13 Fatty Acid Synthesis

11.14 Synthesis of Fatty Acids Other Than Palmitate

11.15 Exercise Speeds Up Fatty Acid Oxidation in Muscle

11.16 Changes in the Plasma Fatty Acid Concentration and Profile During Exercise

11.17 Interconversion of Lipids and Carbohydrates

11.18 Brown Adipose Tissue

11.19 Plasma Lipoproteins

11.20 A Lipoprotein Odyssey

11.21 Effects of Exercise on Plasma Triacylglycerols

11.22 Effects of Exercise on Plasma Cholesterol

11.23 Exercise Increases Ketone Body Formation

Chapter 12. Protein Metabolism in Exercise

12.1 Processing of Dietary Proteins

12.2 Protein Content of the Human Body

12.3 Protein Turnover

12.4 Effects of Exercise on Protein Turnover

12.5 Amino Acid Degradation

12.6 Amino Acid Synthesis

12.7 Effects of Exercise on Amino Acid Metabolism in Muscle

12.8 Effects of Exercise on Amino Acid Metabolism in the Liver

12.9 The Urea Cycle

12.6 Amino Acid Synthesis

12.10 Plasma Amino Acid, Ammonia, and Urea Concentrations During Exercise

12.11 Contribution of Proteins to the Energy Expenditure of Exercise

12.12 Effects of Training on Protein Turnover

Chapter 13. Effects of Exercise on Gene Expression

13.1 Stages in the Control of Gene Expression

13.2 Stages in the Control of Gene Expression Affected by Exercise

13.3 Kinetics of a Gene Product After Exercise

13.4 Exercise-Induced Changes That May Modify Gene Expression

13.5 Mechanisms of Exercise-Induced Muscle Hypertrophy

13.6 Mechanisms of Exercise-Induced Increase in Muscle-Mitochondrial Content

13.7 Exercise and Epigenetics

Chapter 14. Integration of Exercise Metabolism

14.1 Interconnections of Metabolic Pathways

14.2 Energy Systems

14.3 Energy Sources in Exercise

14.4 Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.5 Effect of Exercise Intensity on the Choice of Energy Sources

14.6 Effect of Exercise Duration on the Choice of Energy Sources

14.7 Interplay of Duration and Intensity: Energy Sources in Running and Swimming

14.8 Effect of the Exercise Program on the Choice of Energy Sources

14.9 Sex Differences in the Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.10 How Sex Influences the Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.11 Effect of Age on the Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.12 Effect of Carbohydrate Intake on the Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.13 Effect of Fat Intake on the Choice of Energy Sources During Exercise

14.14 Adaptations of the Proportion of Energy Sources During Exercise to Endurance Training

14.15 How Endurance Training Modifies the Proportion of Energy Sources During Exercise?

14.16 Adaptations of Energy Metabolism to Resistance and Sprint Training

14.17 Adaptations of Exercise Metabolism to Interval Training

14.18 Effect of the Genome on the Choice of Energy Sources in Exercise

14.19 Muscle Fiber Type Transitions

14.20 Effects of Environmental Factors on the Choice of Energy Sources in Exercise

14.21 The Proportion of Fuels Can Be Measured Bloodlessly

14.22 Hormonal Effects on Exercise Metabolism

14.23 Redox State and Exercise Metabolism

14.24 Causes of Fatigue

14.25 Recovery of the Energy State After Exercise

14.26 Metabolic Changes in Detraining

Chapter 15. Exercise to Fight Disease

15.1 Health, Disease, and Exercise

15.2 Exercise to Fight Cardiovascular Disease

15.3 Adaptations of the Heart to Training

15.4 Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

15.5 Exercise to Fight Cancer

15.6 Diabetes, a Major Metabolic Upset

15.7 Exercise to Fight Diabetes

15.8 Obesity, a Health-Threatening Condition

15.9 Why Obesity Is Harmful

15.10 Exercise to Fight Obesity

15.11 Exercise to Fight Osteoporosis

15.12 Exercise to Fight Mental Dysfunction

15.13 The Detriments of Physical Inactivity

15.14 Exercise for Healthy Aging and Longevity

15.15 Benefits From Regular Exercise in Other Diseases

15.16 A Final Word on the Value of Exercise

Part IV. Biochemical Assessment of Exercising Persons

IV.1 The Blood

IV.2 Aims and Scope of the Biochemical Assessment

IV.3 The Reference Interval

IV.4 Classes of Biochemical Parameters

Chapter 16. Iron Status

16.1 Hemoglobin

16.2 Hematologic Parameters

16.3 Does Sports Anemia Exist?

16.4 Iron

16.5 Total Iron-Binding Capacity

16.6 Transferrin Saturation

16.7 Soluble Transferrin Receptor

16.8 Ferritin

16.9 Iron Deficiency

Chapter 17. Metabolites

17.1 Lactate

17.2 Estimating the Anaerobic Lactic Capacity

17.3 Programming Training

17.4 Estimating Aerobic Endurance

17.5 Glucose

17.6 Triacylglycerols

17.7 Cholesterol

17.8 Recapping the Lipidemic Profile

17.9 Glycerol

17.10 Urea

17.11 Ammonia

17.12 Creatinine

17.13 Uric acid

17.14 Glutathione

Chapter 18. Enzymes and Hormones

18.1 Enzymes

18.2 Creatine Kinase

18.3 Glutamyltransferase

18.4 Antioxidant Enzymes

18.5 Steroid Hormones

18.6 Cortisol

18.7 Testosterone

18.8 Overtraining Syndrome

18.9 Epilogue

Part IV Summary

Vassilis Mougios, PhD, is a professor of exercise biochemistry and director of the Laboratory of Evaluation of Human Biological Performance at the University of Thessaloniki in Greece. A teacher of exercise biochemistry, sport nutrition, and ergogenic aspects of sport for 30 years, Mougios served on the Scientific Committee of the 2004 Pre-Olympic Congress. He has coauthored many articles in international scientific journals and has done research on muscle contraction, exercise metabolism, biochemical assessment of athletes, and sport nutrition.

Mougios is a member of the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Physiological Society. He is a fellow and member of the reviewing panel of the European College of Sport Science. He serves as a topic editor for Frontiers in Physiology and a reviewer for Journal of Applied Physiology, British Journal of Sports Medicine, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Acta Physiologica, Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, Metabolism, and Obesity. In his leisure time, he enjoys rafting, hiking, and photography.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.

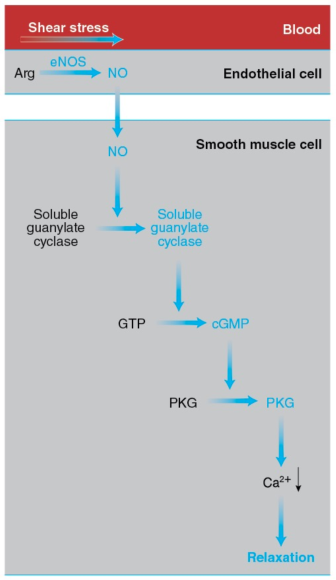

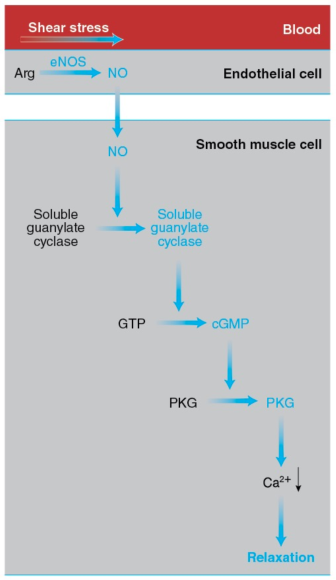

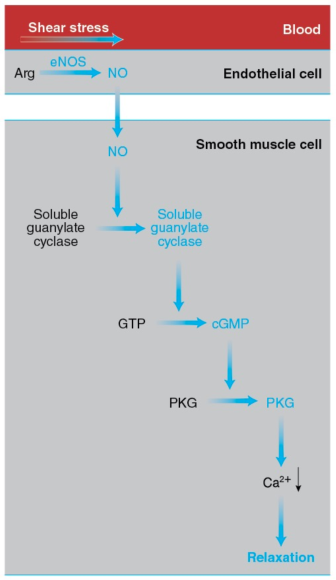

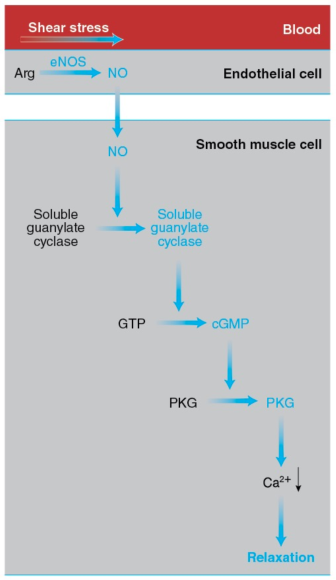

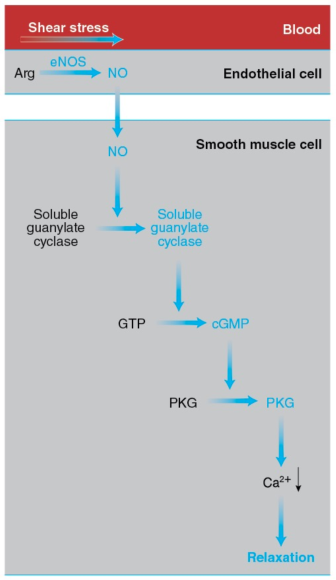

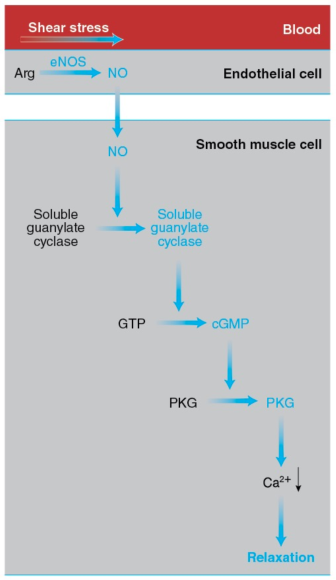

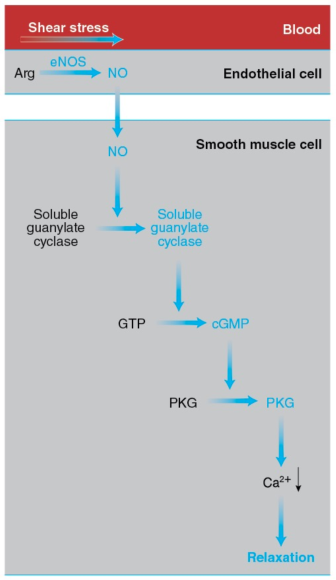

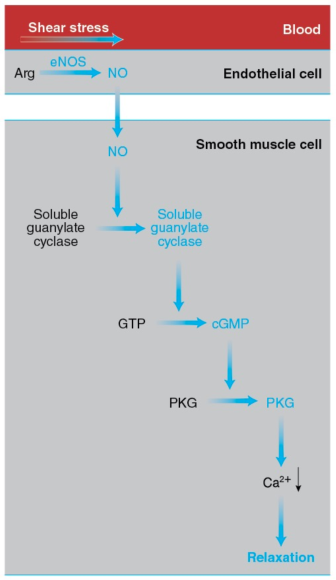

In addition, the increases in blood flow and pressure accompanying exercise cause structural and functional adaptations of the vascular wall that lower the risk of atherosclerosis. These beneficial effects seem to be mediated by the endothelium, the single layer of cells lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, in direct contact with blood on the inside and surrounded by smooth muscle cells on the outside (figure 15.3).

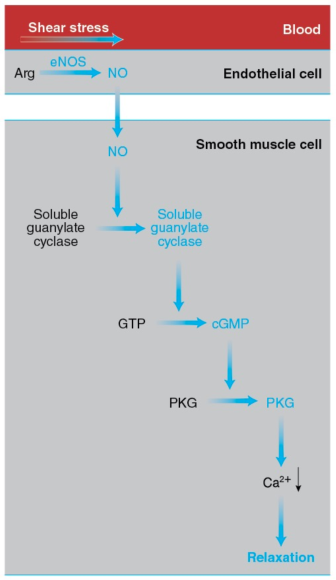

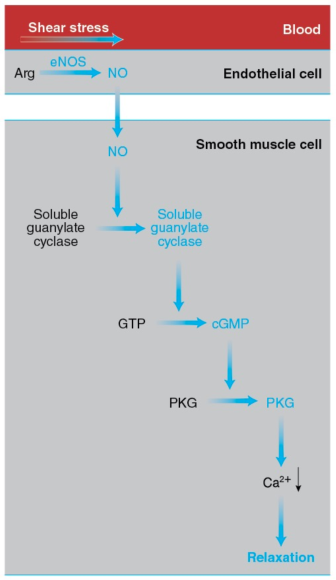

Figure 15.3 How exercise elicits vasodilation. The increase in the pumping activity of the heart during exercise augments the shear stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This mechanical stimulus leads to activation of eNOS, which catalyzes the synthesis of NO from arginine. NO diffuses to the smooth muscle cells forming the walls of blood vessels and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP. Cyclic GMP activates PKG, leading to a drop in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, relaxation of the smooth muscle cells, and vasodilation.

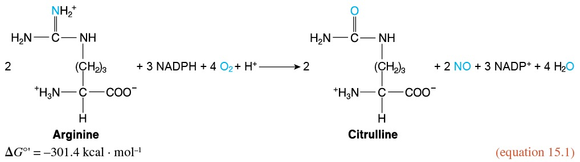

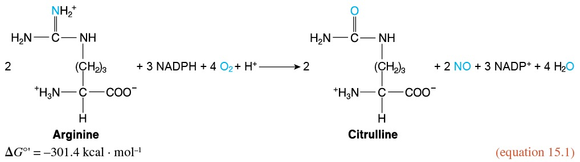

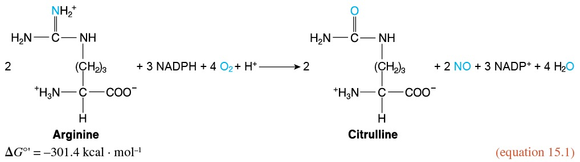

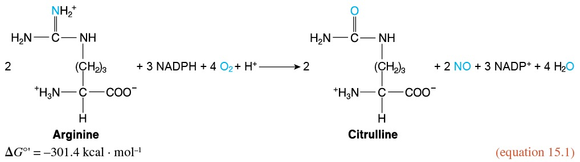

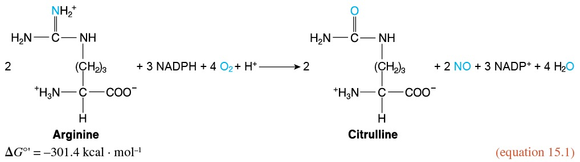

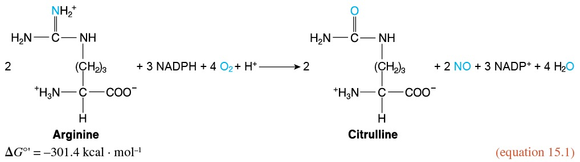

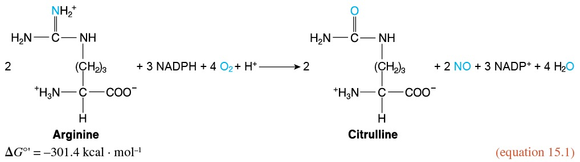

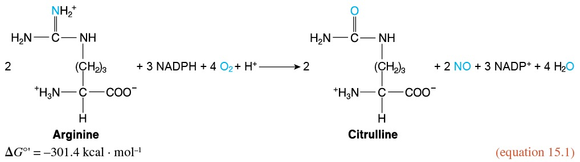

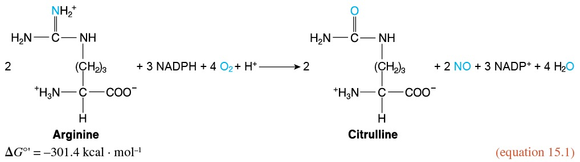

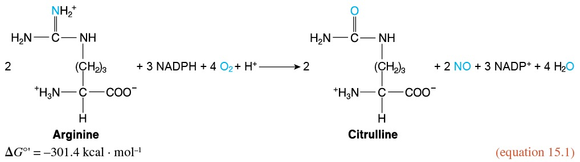

The endothelial cells possess a variety of proteins that convert the mechanical stimulus of the exercise-induced increase in shear stress into chemical signals. In turn, these signals activate endothelial nitrogen oxide synthase (eNOS). This enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nitric oxide (introduced in section 1.5) from arginine and oxygen in a reaction requiring NADPH as a reductant and yielding citrulline (the intermediate compound of the urea cycle introduced in section 12.9 and figure 12.10) in addition to NO.

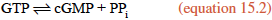

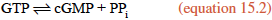

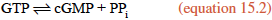

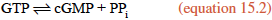

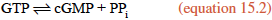

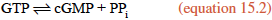

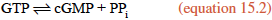

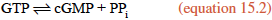

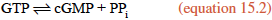

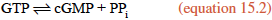

NO diffuses out of the endothelial cells and enters neighboring smooth muscle cells, where it activates soluble guanylate cyclase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanylate, or cyclic GMP (cGMP), from GTP, in a manner analogous to the synthesis of cAMP (section 10.6 and reaction 10.5).

Cyclic GMP, in turn, activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, or PKG, which promotes smooth muscle relaxation by activating an ion pump that removes Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus preventing the interaction of myosin and actin. (Ca2+ allows myosin binding to actin in smooth muscle cells and skeletal muscle fibers through a series of interactions differing from the one described in section 8.10.) Smooth muscle relaxation results in dilation of the blood vessels, or vasodilation. The capacity of the vessels to dilate in response to increased blood flow, a property termed flow-mediated dilation, is considered an index of cardiovascular health.

As Green and coworkers review, training improves flow-mediated dilation—especially in individuals with or at risk of CVD—and reduces arterial wall stiffness by enhancing the endothelium-dependent signal transduction pathway described earlier. The enhancement includes higher eNOS content or activity. It is also possible that training influences other pathways of flow-mediated dilation. In addition, training increases the diameter of vessels—such as the coronary arteries, as well as arteries that nourish the exercising limbs—thus supplying more blood where it is needed. The stimulus, again, appears to be the increased shear stress imposed by blood on the endothelium with exercise.

Finally, training influences the smaller blood vessels: It increases the amount and diameter of the arterioles (the branches of arteries leading to capillaries) and muscle capillarization. The latter is measured as either the total number of capillaries in a muscle, or the number of capillaries per muscle fiber, or capillary density (defined in section 14.15 as the number of capillaries per unit of muscle cross-sectional area). Increased capillarization enhances the delivery of nutrients and O2 to muscle, as well as the uptake of muscle CO2 by blood.

Training-induced capillarization may be due to increased blood flow or to muscle activity itself. Both factors may promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key angiogenic (that is, vessel-generating) protein, from muscle fibers. VEGF binds to the VEGF receptor in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells and activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, leading to endothelial cell proliferation and, hence, formation of new capillaries.

You can see that training provides more than one way of increasing blood supply to the active muscles. It seems that these beneficial adaptations can be elicited by endurance, resistance, and interval training. Improvements in vascular function with training are evident in both healthy humans and (possibly more evident) humans with or at risk of CVD.

Control of Muscle Activity by Ca2+

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered.

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered. Today we know that Ca2+ controls muscle activity and that it does so by permitting the binding of myosin to F-actin. This action of Ca2+ is not direct but indirect. As the Japanese physiologist Setsuro Ebashi discovered in the 1960s, control is exerted through tropomyosin and troponin, the two proteins that coexist with actin in the thin filaments, constituting about one third of the thin-filament mass. Let's meet them.

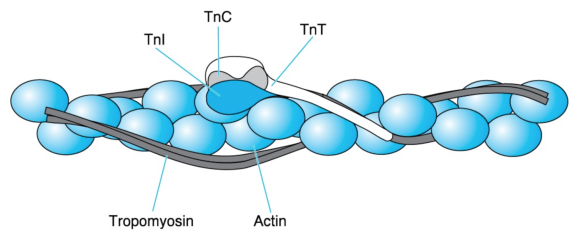

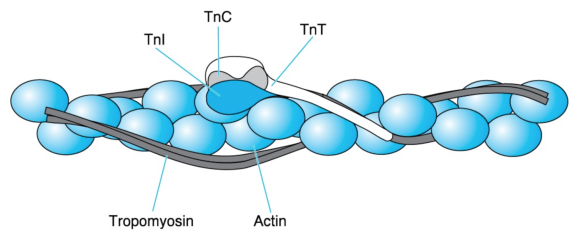

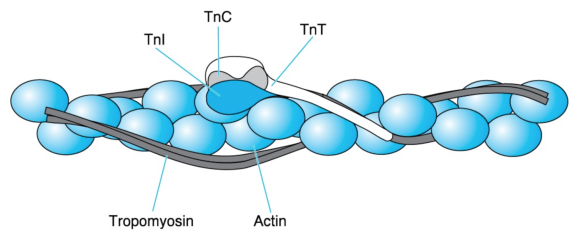

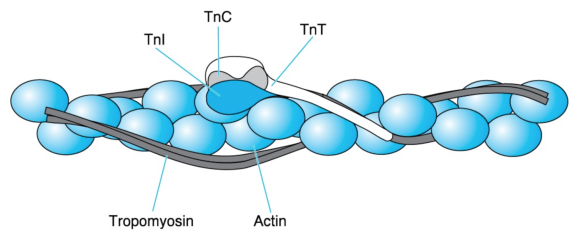

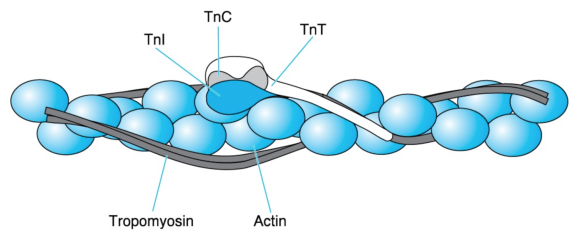

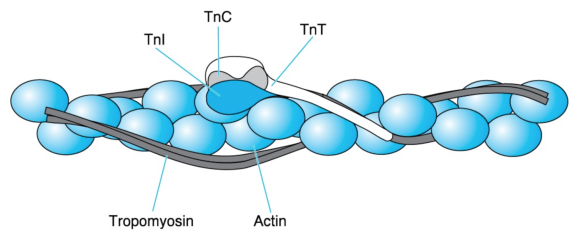

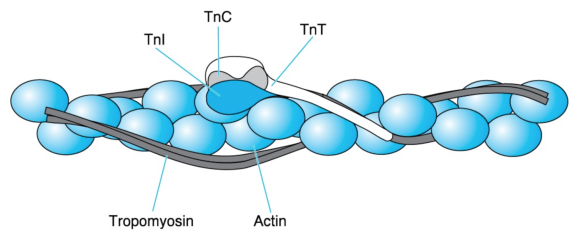

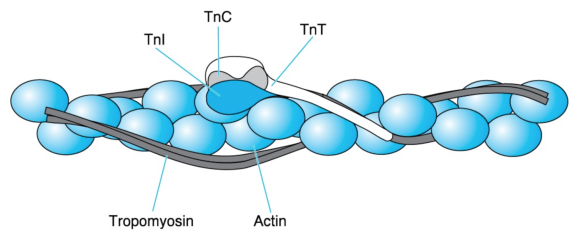

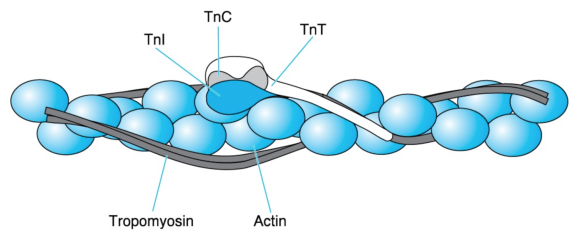

Tropomyosin has a molecular mass of 70 kDa and consists of two similar stringlike subunits in -helical conformation. The two subunits wind around each other just as the myosin heavy chains do in the myosin tail. The resulting extremely long tropomyosin molecules join in a row to form fibers. Two such fibers run along each thin filament while following the twisting of the actin monomers (figure 8.11).

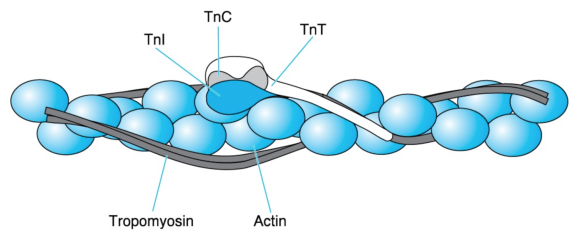

Figure 8.11 Thin-filament proteins. A thin filament consists of an F-actin fiber (the double necklace of figure 8.7), two series of tropomyosin molecules, and troponin (Tn) complexes placed at regular intervals. Each troponin complex consists of TnC, which is the Ca2+ acceptor; TnI, which binds to actin; and TnT, which extends by way of a long tail along tropomyosin.

Adapted from L. Smillie and S. Ebashi, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 10, edited by P.N. Campbell and F. Dickens (Orlando, FL: Academic, 1974), 1-35; C. Cohen Scientific America 233 (1975): 36 - 45. Courtesy of L. Smillie.

Troponin, symbolized as Tn, is a complex of three different subunits: TnC (18 kDa), TnI (24 kDa), and TnT (37 kDa). TnC binds Ca2+, TnI binds to actin, and TnT binds to tropomyosin. Two troponin complexes appear on the two sides of a thin filament every 39 nm, which is approximately the length of a tropomyosin molecule. One troponin complex attached to one tropomyosin molecule controls approximately seven actin monomers.

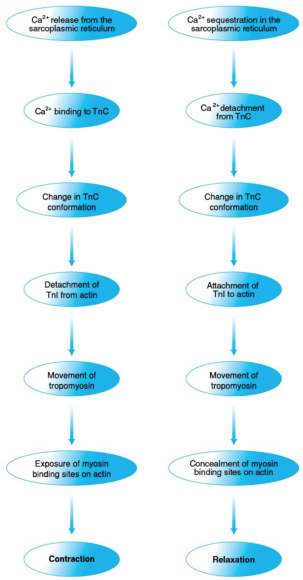

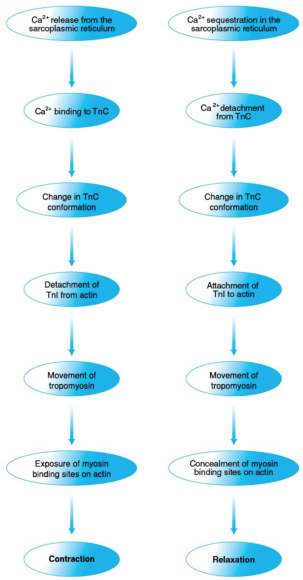

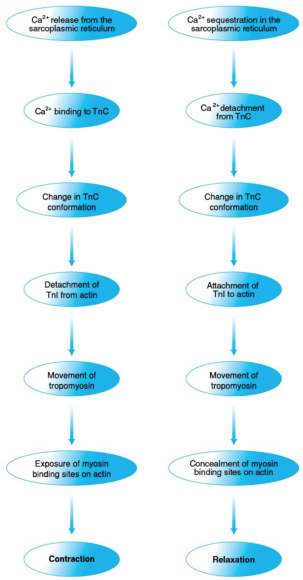

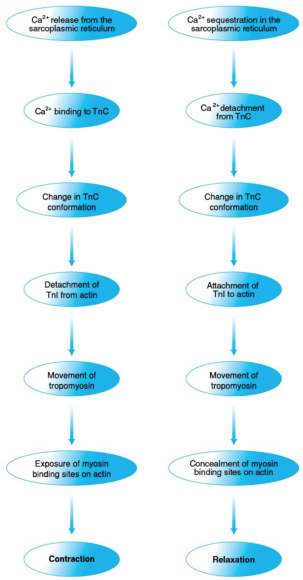

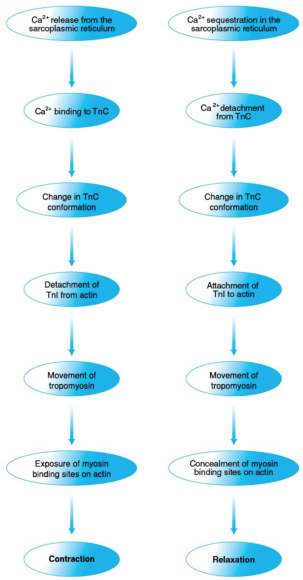

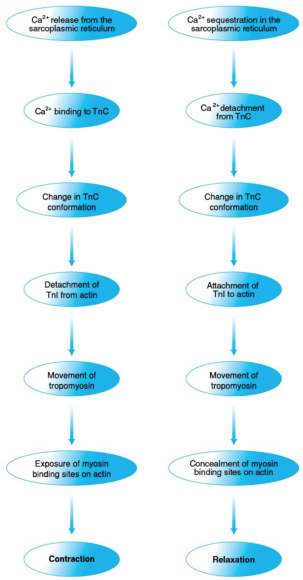

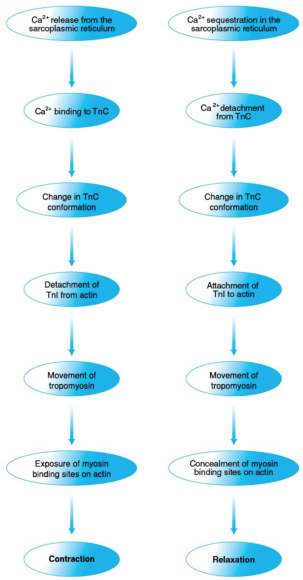

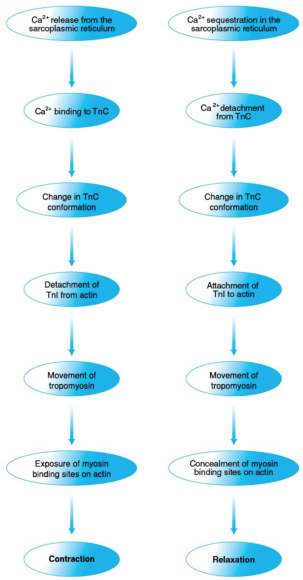

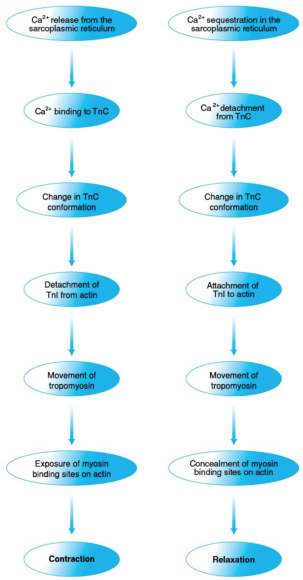

When a muscle is at rest (relaxed), the cytosol has a very low [Ca2+], approximately 10-7 mol · L-1. Researchers believe that, in this case, interactions among F-actin, TnI, TnT, and tropomyosin hold the latter close to the sites on the actin monomers where the myosin heads bind. Thus, tropomyosin hinders the interaction of thin and thick filaments. As we will see in the next section, muscle excitation by the nervous system results in the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular reservoir called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This release causes a 100-fold surge in the cytosolic [Ca2+], from 10-7 to 10-5 mol · L-1.

The increased Ca2+ ions encounter TnC, bind to it, and elicit a change in its conformation. As a result, TnC detaches TnI from F-actin. This detachment lets tropomyosin move over the surface of the thin filament, away from the binding sites of myosin on F-actin. Myosin then binds to F-actin, and the muscle contracts. In fact, there is evidence that myosin binding to F-actin is cooperative; that is, the binding of some myosin heads facilitates the binding of additional ones by promoting the displacement of tropomyosin. This effect is reminiscent of the cooperative binding of O2 to hemoglobin (section 3.12).

Muscle activity continues until Ca2+ is sequestered in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (in a manner that we will examine shortly). The actin-TnI-TnT-tropomyosin interaction is then restored. Tropomyosin returns to a position hindering cross-bridge formation, and the muscle relaxes. The chain of events through which Ca2+ controls muscle contraction is summarized in figure 8.12.

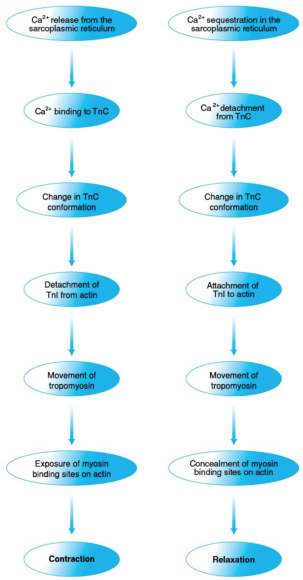

Figure 8.12 Control of muscle contraction and relaxation by Ca2+. Ca2+ controls muscle contraction (left) and relaxation (right) through a series of protein interactions triggered by, respectively, Ca2+ release from and sequestration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and involving troponin, tropomyosin, actin, and myosin.

What are triacylglycerols, and how do they serve us?

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils.

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils. Because of this abundance, they constitute 90% to 95% of dietary fat. In both animals and plants, triacylglycerols serve mainly as energy depots.

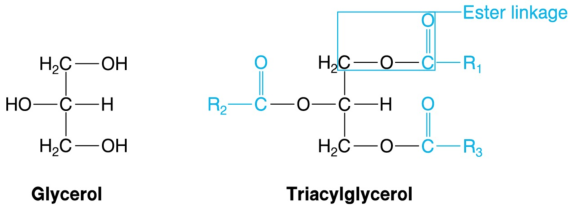

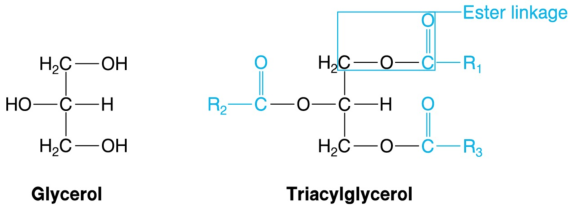

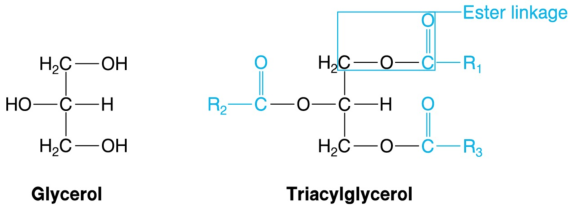

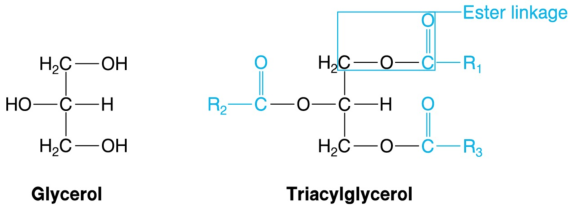

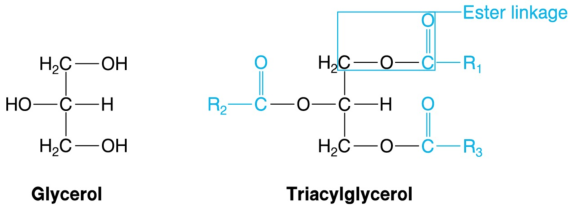

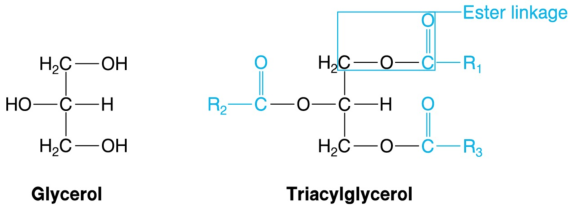

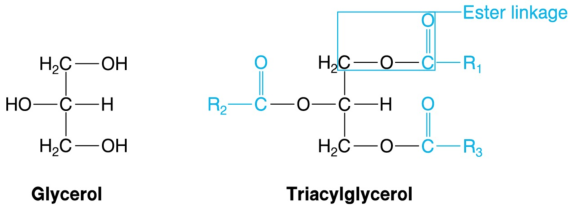

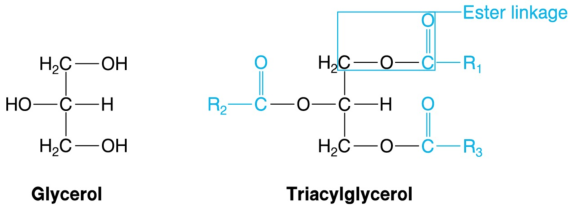

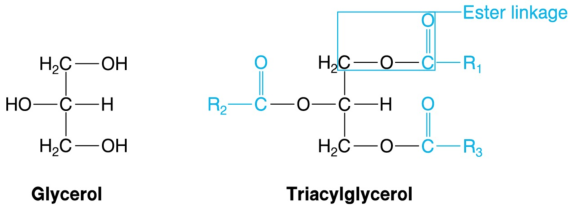

A triacylglycerol consists of a glycerol unit and three fatty acid units. Glycerol (figure 5.12), also known as glycerin or glycerine, is a compound of three carbons and three hydroxyl groups, each of which connects with the carboxyl group of a fatty acid to form an ester linkage. Thus, every triacylglycerol (figure 5.12) contains three ester linkages, which makes it a triester.

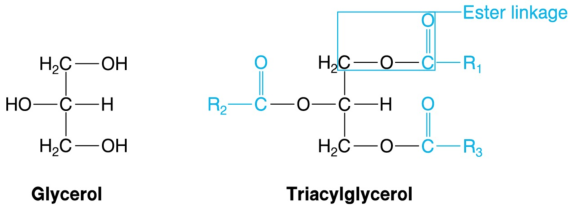

Figure 5.12 Glycerol and triacylglycerol. Triacylglycerols, the largest energy depot in living organisms, are triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. R1, R2, and R3 represent the aliphatic chains of the fatty acids, which usually differ. Acyl groups are shown in color.

Because there is a great variety of available fatty acids, and because any of them can be linked to any of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol, we end up with an even greater variety of triacylglycerols. Chances are that there will be both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids present in a single triacylglycerol. Therefore, it is not accurate to state that a certain food contains only saturated or unsaturated fat. Instead, one should state that a certain food contains primarily saturated or unsaturated fatty acids.

Triacylglycerols are hydrophobic, which is evident by the immiscibility of fats or oils with water. Moreover, triacylglycerols have low thermal conductivity, rendering the subcutaneous fat of animals an efficient insulator of their internal organs against cold exposure.

The part of a fatty acid connected to an oxygen of glycerol in a triacylglycerol is called an acyl group. This is where the term tri-acyl-glycerol comes from; hence it is more accurate than triglyceride. The acyl groups derive from the ion of a fatty acid by removal of O-, and they bear the name of the fatty acid with the ending -oyl in place of -ate. Thus, the acyl group of palmitate is called the palmitoyl group.

The difference in melting point between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids described in the previous section is reflected in triacylglycerols: The more saturated acyl groups they contain, the higher their melting point is. Triacylglycerols of animal origin have a high content of saturated acyl groups, which is why animal fat is solid at room temperature. Conversely, plant triacylglycerols have a high content of unsaturated acyl groups, which is why vegetable oils are liquid in the same conditions.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.

In addition, the increases in blood flow and pressure accompanying exercise cause structural and functional adaptations of the vascular wall that lower the risk of atherosclerosis. These beneficial effects seem to be mediated by the endothelium, the single layer of cells lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, in direct contact with blood on the inside and surrounded by smooth muscle cells on the outside (figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 How exercise elicits vasodilation. The increase in the pumping activity of the heart during exercise augments the shear stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This mechanical stimulus leads to activation of eNOS, which catalyzes the synthesis of NO from arginine. NO diffuses to the smooth muscle cells forming the walls of blood vessels and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP. Cyclic GMP activates PKG, leading to a drop in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, relaxation of the smooth muscle cells, and vasodilation.

The endothelial cells possess a variety of proteins that convert the mechanical stimulus of the exercise-induced increase in shear stress into chemical signals. In turn, these signals activate endothelial nitrogen oxide synthase (eNOS). This enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nitric oxide (introduced in section 1.5) from arginine and oxygen in a reaction requiring NADPH as a reductant and yielding citrulline (the intermediate compound of the urea cycle introduced in section 12.9 and figure 12.10) in addition to NO.

NO diffuses out of the endothelial cells and enters neighboring smooth muscle cells, where it activates soluble guanylate cyclase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanylate, or cyclic GMP (cGMP), from GTP, in a manner analogous to the synthesis of cAMP (section 10.6 and reaction 10.5).

Cyclic GMP, in turn, activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, or PKG, which promotes smooth muscle relaxation by activating an ion pump that removes Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus preventing the interaction of myosin and actin. (Ca2+ allows myosin binding to actin in smooth muscle cells and skeletal muscle fibers through a series of interactions differing from the one described in section 8.10.) Smooth muscle relaxation results in dilation of the blood vessels, or vasodilation. The capacity of the vessels to dilate in response to increased blood flow, a property termed flow-mediated dilation, is considered an index of cardiovascular health.

As Green and coworkers review, training improves flow-mediated dilation—especially in individuals with or at risk of CVD—and reduces arterial wall stiffness by enhancing the endothelium-dependent signal transduction pathway described earlier. The enhancement includes higher eNOS content or activity. It is also possible that training influences other pathways of flow-mediated dilation. In addition, training increases the diameter of vessels—such as the coronary arteries, as well as arteries that nourish the exercising limbs—thus supplying more blood where it is needed. The stimulus, again, appears to be the increased shear stress imposed by blood on the endothelium with exercise.

Finally, training influences the smaller blood vessels: It increases the amount and diameter of the arterioles (the branches of arteries leading to capillaries) and muscle capillarization. The latter is measured as either the total number of capillaries in a muscle, or the number of capillaries per muscle fiber, or capillary density (defined in section 14.15 as the number of capillaries per unit of muscle cross-sectional area). Increased capillarization enhances the delivery of nutrients and O2 to muscle, as well as the uptake of muscle CO2 by blood.

Training-induced capillarization may be due to increased blood flow or to muscle activity itself. Both factors may promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key angiogenic (that is, vessel-generating) protein, from muscle fibers. VEGF binds to the VEGF receptor in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells and activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, leading to endothelial cell proliferation and, hence, formation of new capillaries.

You can see that training provides more than one way of increasing blood supply to the active muscles. It seems that these beneficial adaptations can be elicited by endurance, resistance, and interval training. Improvements in vascular function with training are evident in both healthy humans and (possibly more evident) humans with or at risk of CVD.

Control of Muscle Activity by Ca2+

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered.

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered. Today we know that Ca2+ controls muscle activity and that it does so by permitting the binding of myosin to F-actin. This action of Ca2+ is not direct but indirect. As the Japanese physiologist Setsuro Ebashi discovered in the 1960s, control is exerted through tropomyosin and troponin, the two proteins that coexist with actin in the thin filaments, constituting about one third of the thin-filament mass. Let's meet them.

Tropomyosin has a molecular mass of 70 kDa and consists of two similar stringlike subunits in -helical conformation. The two subunits wind around each other just as the myosin heavy chains do in the myosin tail. The resulting extremely long tropomyosin molecules join in a row to form fibers. Two such fibers run along each thin filament while following the twisting of the actin monomers (figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Thin-filament proteins. A thin filament consists of an F-actin fiber (the double necklace of figure 8.7), two series of tropomyosin molecules, and troponin (Tn) complexes placed at regular intervals. Each troponin complex consists of TnC, which is the Ca2+ acceptor; TnI, which binds to actin; and TnT, which extends by way of a long tail along tropomyosin.

Adapted from L. Smillie and S. Ebashi, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 10, edited by P.N. Campbell and F. Dickens (Orlando, FL: Academic, 1974), 1-35; C. Cohen Scientific America 233 (1975): 36 - 45. Courtesy of L. Smillie.

Troponin, symbolized as Tn, is a complex of three different subunits: TnC (18 kDa), TnI (24 kDa), and TnT (37 kDa). TnC binds Ca2+, TnI binds to actin, and TnT binds to tropomyosin. Two troponin complexes appear on the two sides of a thin filament every 39 nm, which is approximately the length of a tropomyosin molecule. One troponin complex attached to one tropomyosin molecule controls approximately seven actin monomers.

When a muscle is at rest (relaxed), the cytosol has a very low [Ca2+], approximately 10-7 mol · L-1. Researchers believe that, in this case, interactions among F-actin, TnI, TnT, and tropomyosin hold the latter close to the sites on the actin monomers where the myosin heads bind. Thus, tropomyosin hinders the interaction of thin and thick filaments. As we will see in the next section, muscle excitation by the nervous system results in the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular reservoir called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This release causes a 100-fold surge in the cytosolic [Ca2+], from 10-7 to 10-5 mol · L-1.

The increased Ca2+ ions encounter TnC, bind to it, and elicit a change in its conformation. As a result, TnC detaches TnI from F-actin. This detachment lets tropomyosin move over the surface of the thin filament, away from the binding sites of myosin on F-actin. Myosin then binds to F-actin, and the muscle contracts. In fact, there is evidence that myosin binding to F-actin is cooperative; that is, the binding of some myosin heads facilitates the binding of additional ones by promoting the displacement of tropomyosin. This effect is reminiscent of the cooperative binding of O2 to hemoglobin (section 3.12).

Muscle activity continues until Ca2+ is sequestered in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (in a manner that we will examine shortly). The actin-TnI-TnT-tropomyosin interaction is then restored. Tropomyosin returns to a position hindering cross-bridge formation, and the muscle relaxes. The chain of events through which Ca2+ controls muscle contraction is summarized in figure 8.12.

Figure 8.12 Control of muscle contraction and relaxation by Ca2+. Ca2+ controls muscle contraction (left) and relaxation (right) through a series of protein interactions triggered by, respectively, Ca2+ release from and sequestration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and involving troponin, tropomyosin, actin, and myosin.

What are triacylglycerols, and how do they serve us?

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils.

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils. Because of this abundance, they constitute 90% to 95% of dietary fat. In both animals and plants, triacylglycerols serve mainly as energy depots.

A triacylglycerol consists of a glycerol unit and three fatty acid units. Glycerol (figure 5.12), also known as glycerin or glycerine, is a compound of three carbons and three hydroxyl groups, each of which connects with the carboxyl group of a fatty acid to form an ester linkage. Thus, every triacylglycerol (figure 5.12) contains three ester linkages, which makes it a triester.

Figure 5.12 Glycerol and triacylglycerol. Triacylglycerols, the largest energy depot in living organisms, are triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. R1, R2, and R3 represent the aliphatic chains of the fatty acids, which usually differ. Acyl groups are shown in color.

Because there is a great variety of available fatty acids, and because any of them can be linked to any of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol, we end up with an even greater variety of triacylglycerols. Chances are that there will be both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids present in a single triacylglycerol. Therefore, it is not accurate to state that a certain food contains only saturated or unsaturated fat. Instead, one should state that a certain food contains primarily saturated or unsaturated fatty acids.

Triacylglycerols are hydrophobic, which is evident by the immiscibility of fats or oils with water. Moreover, triacylglycerols have low thermal conductivity, rendering the subcutaneous fat of animals an efficient insulator of their internal organs against cold exposure.

The part of a fatty acid connected to an oxygen of glycerol in a triacylglycerol is called an acyl group. This is where the term tri-acyl-glycerol comes from; hence it is more accurate than triglyceride. The acyl groups derive from the ion of a fatty acid by removal of O-, and they bear the name of the fatty acid with the ending -oyl in place of -ate. Thus, the acyl group of palmitate is called the palmitoyl group.

The difference in melting point between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids described in the previous section is reflected in triacylglycerols: The more saturated acyl groups they contain, the higher their melting point is. Triacylglycerols of animal origin have a high content of saturated acyl groups, which is why animal fat is solid at room temperature. Conversely, plant triacylglycerols have a high content of unsaturated acyl groups, which is why vegetable oils are liquid in the same conditions.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.

In addition, the increases in blood flow and pressure accompanying exercise cause structural and functional adaptations of the vascular wall that lower the risk of atherosclerosis. These beneficial effects seem to be mediated by the endothelium, the single layer of cells lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, in direct contact with blood on the inside and surrounded by smooth muscle cells on the outside (figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 How exercise elicits vasodilation. The increase in the pumping activity of the heart during exercise augments the shear stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This mechanical stimulus leads to activation of eNOS, which catalyzes the synthesis of NO from arginine. NO diffuses to the smooth muscle cells forming the walls of blood vessels and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP. Cyclic GMP activates PKG, leading to a drop in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, relaxation of the smooth muscle cells, and vasodilation.

The endothelial cells possess a variety of proteins that convert the mechanical stimulus of the exercise-induced increase in shear stress into chemical signals. In turn, these signals activate endothelial nitrogen oxide synthase (eNOS). This enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nitric oxide (introduced in section 1.5) from arginine and oxygen in a reaction requiring NADPH as a reductant and yielding citrulline (the intermediate compound of the urea cycle introduced in section 12.9 and figure 12.10) in addition to NO.

NO diffuses out of the endothelial cells and enters neighboring smooth muscle cells, where it activates soluble guanylate cyclase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanylate, or cyclic GMP (cGMP), from GTP, in a manner analogous to the synthesis of cAMP (section 10.6 and reaction 10.5).

Cyclic GMP, in turn, activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, or PKG, which promotes smooth muscle relaxation by activating an ion pump that removes Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus preventing the interaction of myosin and actin. (Ca2+ allows myosin binding to actin in smooth muscle cells and skeletal muscle fibers through a series of interactions differing from the one described in section 8.10.) Smooth muscle relaxation results in dilation of the blood vessels, or vasodilation. The capacity of the vessels to dilate in response to increased blood flow, a property termed flow-mediated dilation, is considered an index of cardiovascular health.

As Green and coworkers review, training improves flow-mediated dilation—especially in individuals with or at risk of CVD—and reduces arterial wall stiffness by enhancing the endothelium-dependent signal transduction pathway described earlier. The enhancement includes higher eNOS content or activity. It is also possible that training influences other pathways of flow-mediated dilation. In addition, training increases the diameter of vessels—such as the coronary arteries, as well as arteries that nourish the exercising limbs—thus supplying more blood where it is needed. The stimulus, again, appears to be the increased shear stress imposed by blood on the endothelium with exercise.

Finally, training influences the smaller blood vessels: It increases the amount and diameter of the arterioles (the branches of arteries leading to capillaries) and muscle capillarization. The latter is measured as either the total number of capillaries in a muscle, or the number of capillaries per muscle fiber, or capillary density (defined in section 14.15 as the number of capillaries per unit of muscle cross-sectional area). Increased capillarization enhances the delivery of nutrients and O2 to muscle, as well as the uptake of muscle CO2 by blood.

Training-induced capillarization may be due to increased blood flow or to muscle activity itself. Both factors may promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key angiogenic (that is, vessel-generating) protein, from muscle fibers. VEGF binds to the VEGF receptor in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells and activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, leading to endothelial cell proliferation and, hence, formation of new capillaries.

You can see that training provides more than one way of increasing blood supply to the active muscles. It seems that these beneficial adaptations can be elicited by endurance, resistance, and interval training. Improvements in vascular function with training are evident in both healthy humans and (possibly more evident) humans with or at risk of CVD.

Control of Muscle Activity by Ca2+

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered.

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered. Today we know that Ca2+ controls muscle activity and that it does so by permitting the binding of myosin to F-actin. This action of Ca2+ is not direct but indirect. As the Japanese physiologist Setsuro Ebashi discovered in the 1960s, control is exerted through tropomyosin and troponin, the two proteins that coexist with actin in the thin filaments, constituting about one third of the thin-filament mass. Let's meet them.

Tropomyosin has a molecular mass of 70 kDa and consists of two similar stringlike subunits in -helical conformation. The two subunits wind around each other just as the myosin heavy chains do in the myosin tail. The resulting extremely long tropomyosin molecules join in a row to form fibers. Two such fibers run along each thin filament while following the twisting of the actin monomers (figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Thin-filament proteins. A thin filament consists of an F-actin fiber (the double necklace of figure 8.7), two series of tropomyosin molecules, and troponin (Tn) complexes placed at regular intervals. Each troponin complex consists of TnC, which is the Ca2+ acceptor; TnI, which binds to actin; and TnT, which extends by way of a long tail along tropomyosin.

Adapted from L. Smillie and S. Ebashi, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 10, edited by P.N. Campbell and F. Dickens (Orlando, FL: Academic, 1974), 1-35; C. Cohen Scientific America 233 (1975): 36 - 45. Courtesy of L. Smillie.

Troponin, symbolized as Tn, is a complex of three different subunits: TnC (18 kDa), TnI (24 kDa), and TnT (37 kDa). TnC binds Ca2+, TnI binds to actin, and TnT binds to tropomyosin. Two troponin complexes appear on the two sides of a thin filament every 39 nm, which is approximately the length of a tropomyosin molecule. One troponin complex attached to one tropomyosin molecule controls approximately seven actin monomers.

When a muscle is at rest (relaxed), the cytosol has a very low [Ca2+], approximately 10-7 mol · L-1. Researchers believe that, in this case, interactions among F-actin, TnI, TnT, and tropomyosin hold the latter close to the sites on the actin monomers where the myosin heads bind. Thus, tropomyosin hinders the interaction of thin and thick filaments. As we will see in the next section, muscle excitation by the nervous system results in the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular reservoir called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This release causes a 100-fold surge in the cytosolic [Ca2+], from 10-7 to 10-5 mol · L-1.

The increased Ca2+ ions encounter TnC, bind to it, and elicit a change in its conformation. As a result, TnC detaches TnI from F-actin. This detachment lets tropomyosin move over the surface of the thin filament, away from the binding sites of myosin on F-actin. Myosin then binds to F-actin, and the muscle contracts. In fact, there is evidence that myosin binding to F-actin is cooperative; that is, the binding of some myosin heads facilitates the binding of additional ones by promoting the displacement of tropomyosin. This effect is reminiscent of the cooperative binding of O2 to hemoglobin (section 3.12).

Muscle activity continues until Ca2+ is sequestered in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (in a manner that we will examine shortly). The actin-TnI-TnT-tropomyosin interaction is then restored. Tropomyosin returns to a position hindering cross-bridge formation, and the muscle relaxes. The chain of events through which Ca2+ controls muscle contraction is summarized in figure 8.12.

Figure 8.12 Control of muscle contraction and relaxation by Ca2+. Ca2+ controls muscle contraction (left) and relaxation (right) through a series of protein interactions triggered by, respectively, Ca2+ release from and sequestration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and involving troponin, tropomyosin, actin, and myosin.

What are triacylglycerols, and how do they serve us?

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils.

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils. Because of this abundance, they constitute 90% to 95% of dietary fat. In both animals and plants, triacylglycerols serve mainly as energy depots.

A triacylglycerol consists of a glycerol unit and three fatty acid units. Glycerol (figure 5.12), also known as glycerin or glycerine, is a compound of three carbons and three hydroxyl groups, each of which connects with the carboxyl group of a fatty acid to form an ester linkage. Thus, every triacylglycerol (figure 5.12) contains three ester linkages, which makes it a triester.

Figure 5.12 Glycerol and triacylglycerol. Triacylglycerols, the largest energy depot in living organisms, are triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. R1, R2, and R3 represent the aliphatic chains of the fatty acids, which usually differ. Acyl groups are shown in color.

Because there is a great variety of available fatty acids, and because any of them can be linked to any of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol, we end up with an even greater variety of triacylglycerols. Chances are that there will be both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids present in a single triacylglycerol. Therefore, it is not accurate to state that a certain food contains only saturated or unsaturated fat. Instead, one should state that a certain food contains primarily saturated or unsaturated fatty acids.

Triacylglycerols are hydrophobic, which is evident by the immiscibility of fats or oils with water. Moreover, triacylglycerols have low thermal conductivity, rendering the subcutaneous fat of animals an efficient insulator of their internal organs against cold exposure.

The part of a fatty acid connected to an oxygen of glycerol in a triacylglycerol is called an acyl group. This is where the term tri-acyl-glycerol comes from; hence it is more accurate than triglyceride. The acyl groups derive from the ion of a fatty acid by removal of O-, and they bear the name of the fatty acid with the ending -oyl in place of -ate. Thus, the acyl group of palmitate is called the palmitoyl group.

The difference in melting point between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids described in the previous section is reflected in triacylglycerols: The more saturated acyl groups they contain, the higher their melting point is. Triacylglycerols of animal origin have a high content of saturated acyl groups, which is why animal fat is solid at room temperature. Conversely, plant triacylglycerols have a high content of unsaturated acyl groups, which is why vegetable oils are liquid in the same conditions.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.

In addition, the increases in blood flow and pressure accompanying exercise cause structural and functional adaptations of the vascular wall that lower the risk of atherosclerosis. These beneficial effects seem to be mediated by the endothelium, the single layer of cells lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, in direct contact with blood on the inside and surrounded by smooth muscle cells on the outside (figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 How exercise elicits vasodilation. The increase in the pumping activity of the heart during exercise augments the shear stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This mechanical stimulus leads to activation of eNOS, which catalyzes the synthesis of NO from arginine. NO diffuses to the smooth muscle cells forming the walls of blood vessels and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP. Cyclic GMP activates PKG, leading to a drop in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, relaxation of the smooth muscle cells, and vasodilation.

The endothelial cells possess a variety of proteins that convert the mechanical stimulus of the exercise-induced increase in shear stress into chemical signals. In turn, these signals activate endothelial nitrogen oxide synthase (eNOS). This enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nitric oxide (introduced in section 1.5) from arginine and oxygen in a reaction requiring NADPH as a reductant and yielding citrulline (the intermediate compound of the urea cycle introduced in section 12.9 and figure 12.10) in addition to NO.

NO diffuses out of the endothelial cells and enters neighboring smooth muscle cells, where it activates soluble guanylate cyclase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanylate, or cyclic GMP (cGMP), from GTP, in a manner analogous to the synthesis of cAMP (section 10.6 and reaction 10.5).

Cyclic GMP, in turn, activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, or PKG, which promotes smooth muscle relaxation by activating an ion pump that removes Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus preventing the interaction of myosin and actin. (Ca2+ allows myosin binding to actin in smooth muscle cells and skeletal muscle fibers through a series of interactions differing from the one described in section 8.10.) Smooth muscle relaxation results in dilation of the blood vessels, or vasodilation. The capacity of the vessels to dilate in response to increased blood flow, a property termed flow-mediated dilation, is considered an index of cardiovascular health.

As Green and coworkers review, training improves flow-mediated dilation—especially in individuals with or at risk of CVD—and reduces arterial wall stiffness by enhancing the endothelium-dependent signal transduction pathway described earlier. The enhancement includes higher eNOS content or activity. It is also possible that training influences other pathways of flow-mediated dilation. In addition, training increases the diameter of vessels—such as the coronary arteries, as well as arteries that nourish the exercising limbs—thus supplying more blood where it is needed. The stimulus, again, appears to be the increased shear stress imposed by blood on the endothelium with exercise.

Finally, training influences the smaller blood vessels: It increases the amount and diameter of the arterioles (the branches of arteries leading to capillaries) and muscle capillarization. The latter is measured as either the total number of capillaries in a muscle, or the number of capillaries per muscle fiber, or capillary density (defined in section 14.15 as the number of capillaries per unit of muscle cross-sectional area). Increased capillarization enhances the delivery of nutrients and O2 to muscle, as well as the uptake of muscle CO2 by blood.

Training-induced capillarization may be due to increased blood flow or to muscle activity itself. Both factors may promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key angiogenic (that is, vessel-generating) protein, from muscle fibers. VEGF binds to the VEGF receptor in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells and activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, leading to endothelial cell proliferation and, hence, formation of new capillaries.

You can see that training provides more than one way of increasing blood supply to the active muscles. It seems that these beneficial adaptations can be elicited by endurance, resistance, and interval training. Improvements in vascular function with training are evident in both healthy humans and (possibly more evident) humans with or at risk of CVD.

Control of Muscle Activity by Ca2+

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered.

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered. Today we know that Ca2+ controls muscle activity and that it does so by permitting the binding of myosin to F-actin. This action of Ca2+ is not direct but indirect. As the Japanese physiologist Setsuro Ebashi discovered in the 1960s, control is exerted through tropomyosin and troponin, the two proteins that coexist with actin in the thin filaments, constituting about one third of the thin-filament mass. Let's meet them.

Tropomyosin has a molecular mass of 70 kDa and consists of two similar stringlike subunits in -helical conformation. The two subunits wind around each other just as the myosin heavy chains do in the myosin tail. The resulting extremely long tropomyosin molecules join in a row to form fibers. Two such fibers run along each thin filament while following the twisting of the actin monomers (figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Thin-filament proteins. A thin filament consists of an F-actin fiber (the double necklace of figure 8.7), two series of tropomyosin molecules, and troponin (Tn) complexes placed at regular intervals. Each troponin complex consists of TnC, which is the Ca2+ acceptor; TnI, which binds to actin; and TnT, which extends by way of a long tail along tropomyosin.

Adapted from L. Smillie and S. Ebashi, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 10, edited by P.N. Campbell and F. Dickens (Orlando, FL: Academic, 1974), 1-35; C. Cohen Scientific America 233 (1975): 36 - 45. Courtesy of L. Smillie.

Troponin, symbolized as Tn, is a complex of three different subunits: TnC (18 kDa), TnI (24 kDa), and TnT (37 kDa). TnC binds Ca2+, TnI binds to actin, and TnT binds to tropomyosin. Two troponin complexes appear on the two sides of a thin filament every 39 nm, which is approximately the length of a tropomyosin molecule. One troponin complex attached to one tropomyosin molecule controls approximately seven actin monomers.

When a muscle is at rest (relaxed), the cytosol has a very low [Ca2+], approximately 10-7 mol · L-1. Researchers believe that, in this case, interactions among F-actin, TnI, TnT, and tropomyosin hold the latter close to the sites on the actin monomers where the myosin heads bind. Thus, tropomyosin hinders the interaction of thin and thick filaments. As we will see in the next section, muscle excitation by the nervous system results in the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular reservoir called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This release causes a 100-fold surge in the cytosolic [Ca2+], from 10-7 to 10-5 mol · L-1.

The increased Ca2+ ions encounter TnC, bind to it, and elicit a change in its conformation. As a result, TnC detaches TnI from F-actin. This detachment lets tropomyosin move over the surface of the thin filament, away from the binding sites of myosin on F-actin. Myosin then binds to F-actin, and the muscle contracts. In fact, there is evidence that myosin binding to F-actin is cooperative; that is, the binding of some myosin heads facilitates the binding of additional ones by promoting the displacement of tropomyosin. This effect is reminiscent of the cooperative binding of O2 to hemoglobin (section 3.12).

Muscle activity continues until Ca2+ is sequestered in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (in a manner that we will examine shortly). The actin-TnI-TnT-tropomyosin interaction is then restored. Tropomyosin returns to a position hindering cross-bridge formation, and the muscle relaxes. The chain of events through which Ca2+ controls muscle contraction is summarized in figure 8.12.

Figure 8.12 Control of muscle contraction and relaxation by Ca2+. Ca2+ controls muscle contraction (left) and relaxation (right) through a series of protein interactions triggered by, respectively, Ca2+ release from and sequestration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and involving troponin, tropomyosin, actin, and myosin.

What are triacylglycerols, and how do they serve us?

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils.

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils. Because of this abundance, they constitute 90% to 95% of dietary fat. In both animals and plants, triacylglycerols serve mainly as energy depots.

A triacylglycerol consists of a glycerol unit and three fatty acid units. Glycerol (figure 5.12), also known as glycerin or glycerine, is a compound of three carbons and three hydroxyl groups, each of which connects with the carboxyl group of a fatty acid to form an ester linkage. Thus, every triacylglycerol (figure 5.12) contains three ester linkages, which makes it a triester.

Figure 5.12 Glycerol and triacylglycerol. Triacylglycerols, the largest energy depot in living organisms, are triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. R1, R2, and R3 represent the aliphatic chains of the fatty acids, which usually differ. Acyl groups are shown in color.

Because there is a great variety of available fatty acids, and because any of them can be linked to any of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol, we end up with an even greater variety of triacylglycerols. Chances are that there will be both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids present in a single triacylglycerol. Therefore, it is not accurate to state that a certain food contains only saturated or unsaturated fat. Instead, one should state that a certain food contains primarily saturated or unsaturated fatty acids.

Triacylglycerols are hydrophobic, which is evident by the immiscibility of fats or oils with water. Moreover, triacylglycerols have low thermal conductivity, rendering the subcutaneous fat of animals an efficient insulator of their internal organs against cold exposure.

The part of a fatty acid connected to an oxygen of glycerol in a triacylglycerol is called an acyl group. This is where the term tri-acyl-glycerol comes from; hence it is more accurate than triglyceride. The acyl groups derive from the ion of a fatty acid by removal of O-, and they bear the name of the fatty acid with the ending -oyl in place of -ate. Thus, the acyl group of palmitate is called the palmitoyl group.

The difference in melting point between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids described in the previous section is reflected in triacylglycerols: The more saturated acyl groups they contain, the higher their melting point is. Triacylglycerols of animal origin have a high content of saturated acyl groups, which is why animal fat is solid at room temperature. Conversely, plant triacylglycerols have a high content of unsaturated acyl groups, which is why vegetable oils are liquid in the same conditions.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.

In addition, the increases in blood flow and pressure accompanying exercise cause structural and functional adaptations of the vascular wall that lower the risk of atherosclerosis. These beneficial effects seem to be mediated by the endothelium, the single layer of cells lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, in direct contact with blood on the inside and surrounded by smooth muscle cells on the outside (figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 How exercise elicits vasodilation. The increase in the pumping activity of the heart during exercise augments the shear stress on the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels. This mechanical stimulus leads to activation of eNOS, which catalyzes the synthesis of NO from arginine. NO diffuses to the smooth muscle cells forming the walls of blood vessels and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which catalyzes the synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) from GTP. Cyclic GMP activates PKG, leading to a drop in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, relaxation of the smooth muscle cells, and vasodilation.

The endothelial cells possess a variety of proteins that convert the mechanical stimulus of the exercise-induced increase in shear stress into chemical signals. In turn, these signals activate endothelial nitrogen oxide synthase (eNOS). This enzyme catalyzes the synthesis of nitric oxide (introduced in section 1.5) from arginine and oxygen in a reaction requiring NADPH as a reductant and yielding citrulline (the intermediate compound of the urea cycle introduced in section 12.9 and figure 12.10) in addition to NO.

NO diffuses out of the endothelial cells and enters neighboring smooth muscle cells, where it activates soluble guanylate cyclase, a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic guanylate, or cyclic GMP (cGMP), from GTP, in a manner analogous to the synthesis of cAMP (section 10.6 and reaction 10.5).

Cyclic GMP, in turn, activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase, or PKG, which promotes smooth muscle relaxation by activating an ion pump that removes Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus preventing the interaction of myosin and actin. (Ca2+ allows myosin binding to actin in smooth muscle cells and skeletal muscle fibers through a series of interactions differing from the one described in section 8.10.) Smooth muscle relaxation results in dilation of the blood vessels, or vasodilation. The capacity of the vessels to dilate in response to increased blood flow, a property termed flow-mediated dilation, is considered an index of cardiovascular health.

As Green and coworkers review, training improves flow-mediated dilation—especially in individuals with or at risk of CVD—and reduces arterial wall stiffness by enhancing the endothelium-dependent signal transduction pathway described earlier. The enhancement includes higher eNOS content or activity. It is also possible that training influences other pathways of flow-mediated dilation. In addition, training increases the diameter of vessels—such as the coronary arteries, as well as arteries that nourish the exercising limbs—thus supplying more blood where it is needed. The stimulus, again, appears to be the increased shear stress imposed by blood on the endothelium with exercise.

Finally, training influences the smaller blood vessels: It increases the amount and diameter of the arterioles (the branches of arteries leading to capillaries) and muscle capillarization. The latter is measured as either the total number of capillaries in a muscle, or the number of capillaries per muscle fiber, or capillary density (defined in section 14.15 as the number of capillaries per unit of muscle cross-sectional area). Increased capillarization enhances the delivery of nutrients and O2 to muscle, as well as the uptake of muscle CO2 by blood.

Training-induced capillarization may be due to increased blood flow or to muscle activity itself. Both factors may promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key angiogenic (that is, vessel-generating) protein, from muscle fibers. VEGF binds to the VEGF receptor in the plasma membrane of endothelial cells and activates a variety of signal transduction pathways, leading to endothelial cell proliferation and, hence, formation of new capillaries.

You can see that training provides more than one way of increasing blood supply to the active muscles. It seems that these beneficial adaptations can be elicited by endurance, resistance, and interval training. Improvements in vascular function with training are evident in both healthy humans and (possibly more evident) humans with or at risk of CVD.

Control of Muscle Activity by Ca2+

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered.

For more than 130 years (since 1883), it has been known that muscles cannot contract in the absence of calcium cations. However, 80 years had to pass before the exact role of Ca2+ was discovered. Today we know that Ca2+ controls muscle activity and that it does so by permitting the binding of myosin to F-actin. This action of Ca2+ is not direct but indirect. As the Japanese physiologist Setsuro Ebashi discovered in the 1960s, control is exerted through tropomyosin and troponin, the two proteins that coexist with actin in the thin filaments, constituting about one third of the thin-filament mass. Let's meet them.

Tropomyosin has a molecular mass of 70 kDa and consists of two similar stringlike subunits in -helical conformation. The two subunits wind around each other just as the myosin heavy chains do in the myosin tail. The resulting extremely long tropomyosin molecules join in a row to form fibers. Two such fibers run along each thin filament while following the twisting of the actin monomers (figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 Thin-filament proteins. A thin filament consists of an F-actin fiber (the double necklace of figure 8.7), two series of tropomyosin molecules, and troponin (Tn) complexes placed at regular intervals. Each troponin complex consists of TnC, which is the Ca2+ acceptor; TnI, which binds to actin; and TnT, which extends by way of a long tail along tropomyosin.

Adapted from L. Smillie and S. Ebashi, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 10, edited by P.N. Campbell and F. Dickens (Orlando, FL: Academic, 1974), 1-35; C. Cohen Scientific America 233 (1975): 36 - 45. Courtesy of L. Smillie.

Troponin, symbolized as Tn, is a complex of three different subunits: TnC (18 kDa), TnI (24 kDa), and TnT (37 kDa). TnC binds Ca2+, TnI binds to actin, and TnT binds to tropomyosin. Two troponin complexes appear on the two sides of a thin filament every 39 nm, which is approximately the length of a tropomyosin molecule. One troponin complex attached to one tropomyosin molecule controls approximately seven actin monomers.

When a muscle is at rest (relaxed), the cytosol has a very low [Ca2+], approximately 10-7 mol · L-1. Researchers believe that, in this case, interactions among F-actin, TnI, TnT, and tropomyosin hold the latter close to the sites on the actin monomers where the myosin heads bind. Thus, tropomyosin hinders the interaction of thin and thick filaments. As we will see in the next section, muscle excitation by the nervous system results in the release of Ca2+ from an intracellular reservoir called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This release causes a 100-fold surge in the cytosolic [Ca2+], from 10-7 to 10-5 mol · L-1.

The increased Ca2+ ions encounter TnC, bind to it, and elicit a change in its conformation. As a result, TnC detaches TnI from F-actin. This detachment lets tropomyosin move over the surface of the thin filament, away from the binding sites of myosin on F-actin. Myosin then binds to F-actin, and the muscle contracts. In fact, there is evidence that myosin binding to F-actin is cooperative; that is, the binding of some myosin heads facilitates the binding of additional ones by promoting the displacement of tropomyosin. This effect is reminiscent of the cooperative binding of O2 to hemoglobin (section 3.12).

Muscle activity continues until Ca2+ is sequestered in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (in a manner that we will examine shortly). The actin-TnI-TnT-tropomyosin interaction is then restored. Tropomyosin returns to a position hindering cross-bridge formation, and the muscle relaxes. The chain of events through which Ca2+ controls muscle contraction is summarized in figure 8.12.

Figure 8.12 Control of muscle contraction and relaxation by Ca2+. Ca2+ controls muscle contraction (left) and relaxation (right) through a series of protein interactions triggered by, respectively, Ca2+ release from and sequestration in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and involving troponin, tropomyosin, actin, and myosin.

What are triacylglycerols, and how do they serve us?

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils.

Triacylglycerols, or triglycerides, are the most abundant lipid category. They are the main components of animal (including human) fat, most of which is concentrated in adipose tissue; they are also the main components of vegetable oils. Because of this abundance, they constitute 90% to 95% of dietary fat. In both animals and plants, triacylglycerols serve mainly as energy depots.

A triacylglycerol consists of a glycerol unit and three fatty acid units. Glycerol (figure 5.12), also known as glycerin or glycerine, is a compound of three carbons and three hydroxyl groups, each of which connects with the carboxyl group of a fatty acid to form an ester linkage. Thus, every triacylglycerol (figure 5.12) contains three ester linkages, which makes it a triester.

Figure 5.12 Glycerol and triacylglycerol. Triacylglycerols, the largest energy depot in living organisms, are triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. R1, R2, and R3 represent the aliphatic chains of the fatty acids, which usually differ. Acyl groups are shown in color.

Because there is a great variety of available fatty acids, and because any of them can be linked to any of the hydroxyl groups of glycerol, we end up with an even greater variety of triacylglycerols. Chances are that there will be both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids present in a single triacylglycerol. Therefore, it is not accurate to state that a certain food contains only saturated or unsaturated fat. Instead, one should state that a certain food contains primarily saturated or unsaturated fatty acids.

Triacylglycerols are hydrophobic, which is evident by the immiscibility of fats or oils with water. Moreover, triacylglycerols have low thermal conductivity, rendering the subcutaneous fat of animals an efficient insulator of their internal organs against cold exposure.

The part of a fatty acid connected to an oxygen of glycerol in a triacylglycerol is called an acyl group. This is where the term tri-acyl-glycerol comes from; hence it is more accurate than triglyceride. The acyl groups derive from the ion of a fatty acid by removal of O-, and they bear the name of the fatty acid with the ending -oyl in place of -ate. Thus, the acyl group of palmitate is called the palmitoyl group.

The difference in melting point between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids described in the previous section is reflected in triacylglycerols: The more saturated acyl groups they contain, the higher their melting point is. Triacylglycerols of animal origin have a high content of saturated acyl groups, which is why animal fat is solid at room temperature. Conversely, plant triacylglycerols have a high content of unsaturated acyl groups, which is why vegetable oils are liquid in the same conditions.

Adaptations of the Vasculature to Training

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol.

Training benefits the blood vessels as well as the heart. As discussed in sections 11.21 and 11.22, endurance and resistance training can lower the risk of atherosclerosis by decreasing plasma triacylglycerols, total cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. On top of these effects, endurance training contributes to lowering the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing HDL cholesterol.