Learn how to maximize training gains with Tudor O. Bompa, the pioneer of periodization training, and Carlo A. Buzzichelli, one of the world’s foremost experts on training methods, in the sixth edition of Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training. Guided by the authors’ expertise, the sixth edition offers information central to understanding the latest research and practices related to training theory while providing scientific support for the fundamental principles of periodization.

The sixth edition of this definitive text presents a comprehensive discussion of periodization based on the philosophy of Tudor Bompa. It features the following:

• A review of the history, terms, and theories related to periodization

• Discussion of the importance of designing a sport-specific and competition-level annual plan and discarding any one-size-fits-all approach

• An expanded chapter on the integration of biomotor abilities within the training process

• Comprehensive updates to the information on training sessions, microcycles, and macrocycles

• An expanded chapter on the methods for developing muscle strength, including manipulation of loading variables and the conversion to specific strength

• A more detailed explanation of speed and agility training, differentiating between individual and team sports

In addition to applying periodization models to resistance training, Periodization also discusses sport-specific endurance. You’ll be introduced to different methods of testing and developing endurance, including the physiological basis for each method.

Instructors will also find a newly added image bank, allowing access to tables and figures in the text for use when creating lecture materials.

Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training presents the latest refinements to Bompa’s theories on periodization to help you create training programs that enhance sport skills and ensure peak performance.

Part I. Training Theory

Chapter 1. Basis for Training

Scope of Training

Objectives of Training

Classification of Skills

System of Training

Adaptation

Supercompensation Cycle and Adaptation

Sources of Energy

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 2. Principles of Training

Multilateral Development Versus Specialization

Individualization

Development of the Training Model

Load Progression

Sequence of the Training Load

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 3. Preparation for Training

Physical Training

Exercise for Physical Training

Technical Training

Tactical Training

Theoretical Training

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 4. Variables of Training

Volume

Intensity

Relationship Between Volume and Intensity

Frequency

Complexity

Index of Overall Demand

Summary of Major Concepts

Part II. Planning and Periodization

Chapter 5. Periodization of Biomotor Abilities

Brief History of Periodization

Periodization Terminology

Applying Periodization to the Development of Biomotor Abilities

Simultaneous Versus Sequential Integration of Biomotor Abilities

Periodization of Strength

Periodization of Power, Agility, and Movement Time

Periodization of Speed

Periodization of Endurance

Integrated Periodization

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 6. Planning the Training Session

Importance of Planning

Planning Requirements

Types of Training Plans

Training Session

Daily Cycle of Training

Modeling the Training Session Plan

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 7. Planning the Training Cycles

Microcycle

Macrocycle

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 8. Periodization of the Annual Plan

Annual Training Plan and Its Characteristics

Classifying Annual Plans

Chart of the Annual Training Plan

Criteria for Compiling an Annual Plan

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 9. Peaking for Competition

Training Conditions for Peaking

Peaking

Defining a Taper

Competition Phase of the Annual Plan

Identifying Peaking

Maintaining a Peak

Summary of Major Concepts

Part III. Training Methods

Chapter 10. Strength and Power Development

The Relationship Between the Main Biomotor Abilities

Strength

Methods of Strength Training

Manipulation of Training Variables

Implementation of a Strength Training Program

Periodization of Strength

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 11. Endurance Training

Classification of Endurance

Factors Affecting Aerobic Endurance Performance

Factors Affecting Anaerobic Endurance Performance

Methods for Developing Endurance

Methods for Developing High-Intensity Exercise Endurance

Periodization of Endurance

Summary of Major Concepts

Chapter 12. Speed and Agility Training

Speed Training

Agility Training

Program Design

Periodization of Speed and Agility Training

Summary of Major Concepts

Tudor O. Bompa, PhD, revolutionized Western training methods when he introduced his groundbreaking theory of periodization in his native Romania in 1963. After adopting his training system, the Eastern Bloc countries dominated international sports through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1988, Bompa began applying his principles of periodization to the sport of bodybuilding. He has personally trained 11 Olympic medalists (including four gold medalists) and has served as a consultant to coaches and athletes worldwide.

Bompa’s books on training methods, including Theory and Methodology of Training: The Key to Athletic Performance and Periodization of Training for Sports, have been translated into 19 languages and used in more than 180 countries for training athletes and educating and certifying coaches. Bompa has been invited to speak about training in more than 30 countries and has been awarded certificates of honor and appreciation from such prestigious organizations as the Ministry of Culture of Argentina, the Australian Sports Council, the Spanish Olympic Committee, NSCA (2014 Alvin Roy Award for Career Achievement), and the International Olympic Committee.

A member of the Canadian Olympic Association and the Romanian National Council of Sports, Bompa is a professor emeritus at York University, where he taught training theories since 1987. In 2017, Bompa was awarded the honorary title of doctor honoris causa in his home country of Romania. He and his wife, Tamara, live in Sharon, Ontario.

Carlo A. Buzzichelli is a PhD candidate at the Superior Institute of Physical Culture and Sports of Havana (Cuba), a professional strength and conditioning coach, the director of the International Strength and Conditioning Institute, a consultant for the Cuban track and field Olympic team, an adjunct professor of theory and methodology of training at the University of Milan (Italy), and a member of the President’s Program Advisory Council of the International Sports Sciences Association (ISSA). Buzzichelli has held seminars and lectures at various universities and sport institutes worldwide and was an invited lecturer at the 2012 International Workshop on Strength and Conditioning of Trivandrum (India), the 2015 Performance Training Summit of Beijing (China), the 2016 International Workshop on Strength and Conditioning in Bucharest (Romania), and the 2017 Track and Field National Team Coaches Forum in Havana.

Buzzichelli’s coaching experience includes the 2002 Commonwealth Games, the 2003 and 2017 World Track and Field Championships, and the 2016 Summer Olympics. As a strength and conditioning coach for team sports, his senior teams have achieved a first place and a second place in their respective league cups, and his junior teams have won two regional cups. As a coach of individual sports, Buzzichelli’s athletes have won 23 medals at national championships in four different sports (track and field, swimming, Brazilian jiujitsu, and powerlifting), set nine national records in powerlifting and track and field, and won 10 medals at international competitions. In 2015, Buzzichelli coached two Italian champions in two different sports; in 2016, two of his athletes earned international titles in two different combat sports.

Link training periods with a transition phase

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan.

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan. The transition phase serves an important role in preparing the athlete for the next training cycle. The athlete should start the new preparatory phase only when fully recovered from the previous competitive season. If the athlete initiates a new preparatory phase without full recovery, it is likely that performances will be impaired in future competitive cycles and the risk of injury will increase.

The transition phase, often inappropriately called the off-season, links two annual training plans. This phase facilitates psychological rest, relaxation, and biological regeneration while maintaining an acceptable level of general physical preparation (40% to 50% of the competitive phase). Training should be low key: All loading factors should be reduced; the main training components should be centered on general training, with minimal, if any, technical or tactical development. The transition phase generally should last 2 to 4 weeks but could be extended to 6 weeks, especially for younger athletes. Under normal circumstances the transition phase should not last longer than 6 weeks.

There are two common approaches to the transition phase. The first (incorrect) approach encourages complete rest with no physical activity; in this case, the term off-season fits perfectly. This abrupt interruption of training and the complete inactivity can lead to significant detraining even if only undertaken for a short period of time (

Some authors have suggested that an abrupt cessation of training by highly trained athletes creates a phenomenon known as detraining syndrome, relaxation syndrome, exercise abstinence, or exercise dependency syndrome. This type of detraining appears to occur in athletes who either intentionally cease training or are forced to stop training in response to an injury. Detraining syndrome can be characterized by many symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, depression, alterations to cardiovascular function, and a loss of appetite (see the sidebar, Potential Symptoms of Detraining Syndrome, for additional symptoms). These symptoms usually are not pathological and can be reversed if training is resumed within a short time. If the cessation of training is prolonged, these symptoms can become more pronounced, indicating that the athlete's body is unable to adapt to this sudden inactivity. The time frame in which these symptoms manifest themselves is highly specific to the individual athlete; generally, it can occur within 2 to 3 weeks of inactivity and varies in severity.

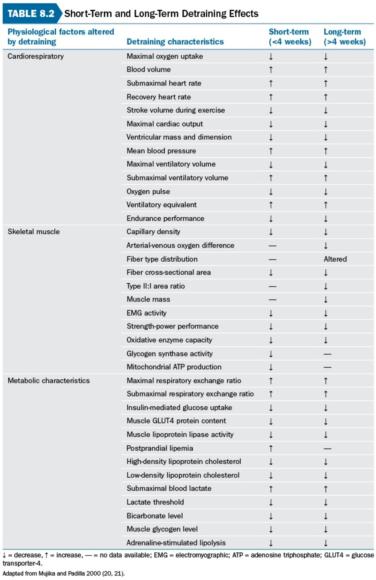

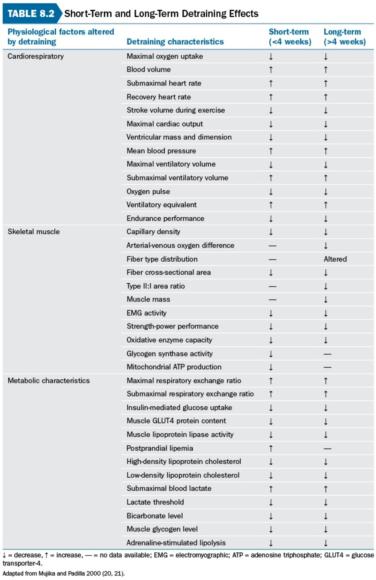

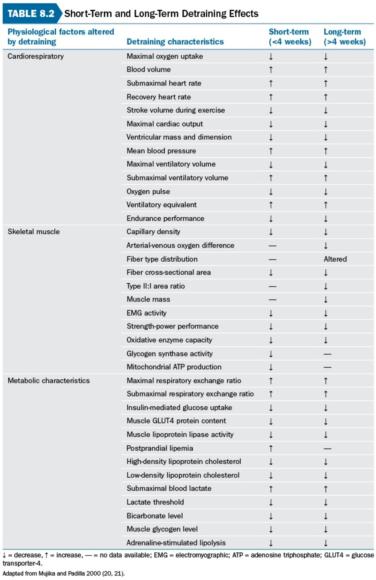

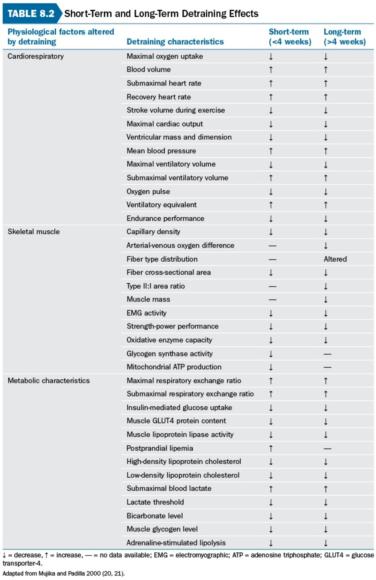

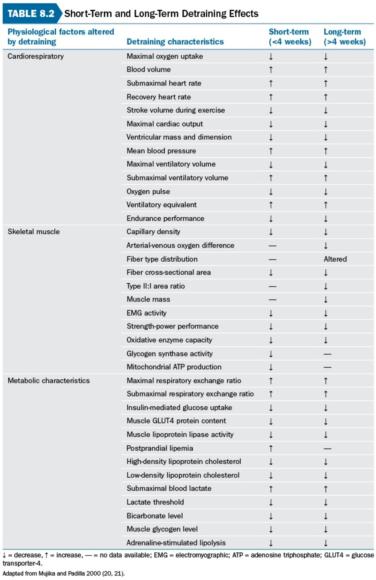

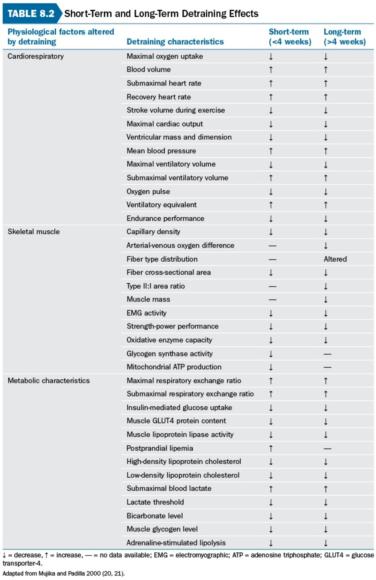

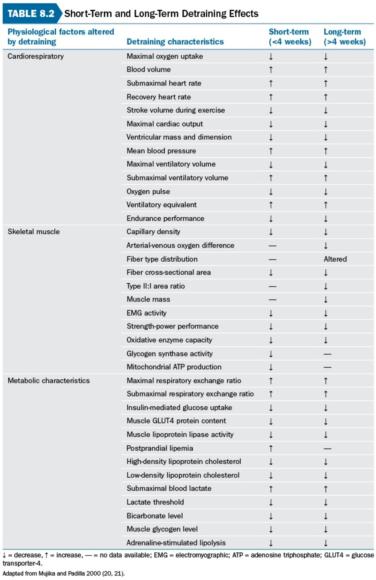

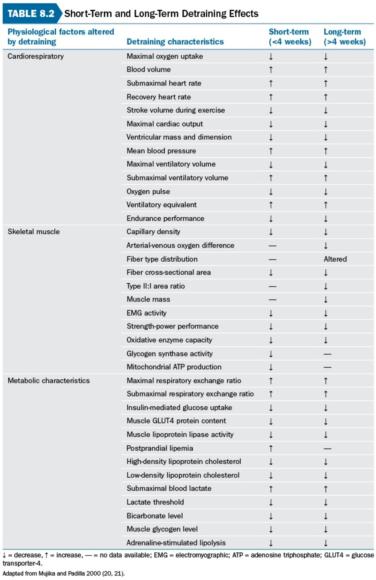

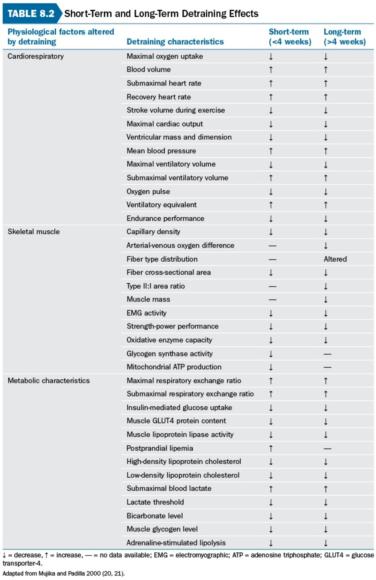

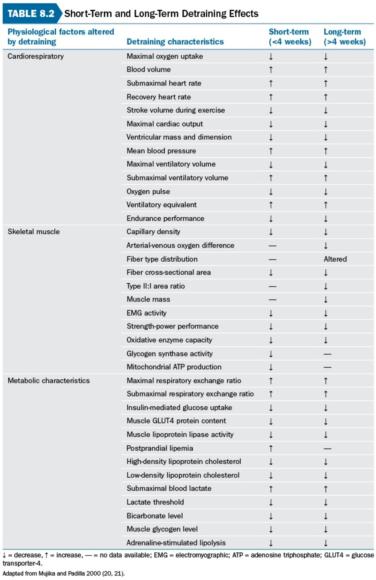

Simply decreasing the level of training can also stimulate a detraining effect that will decrease physiological (table 8.2) and performance capacity. The magnitude of the detraining effects will be related to the duration of the detraining period. Short-term detraining, which occurs in less than 4 weeks, can result in some significant decreases in endurance and strength performance.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Understand the objectives of training

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible.

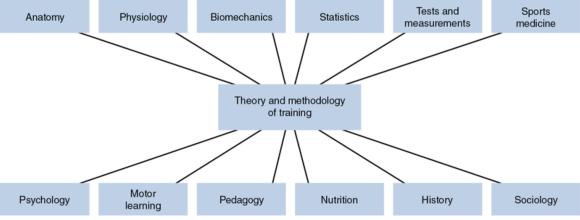

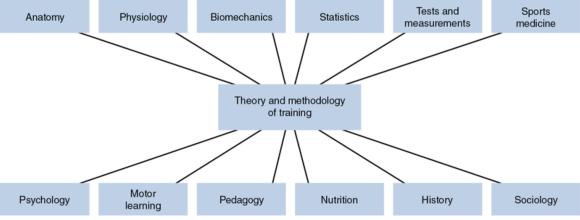

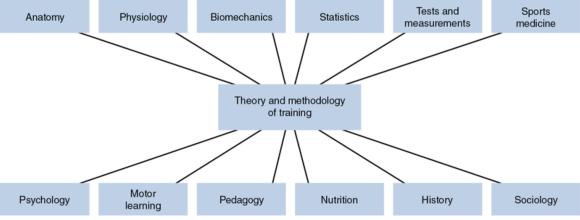

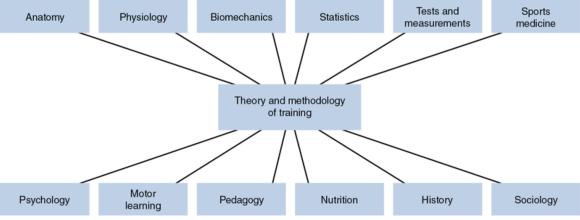

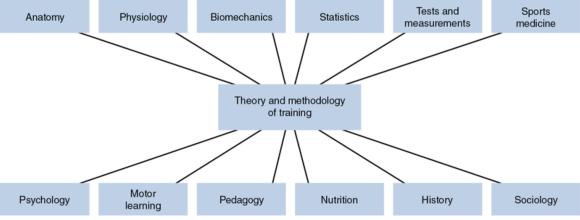

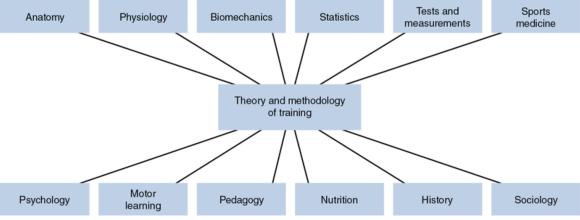

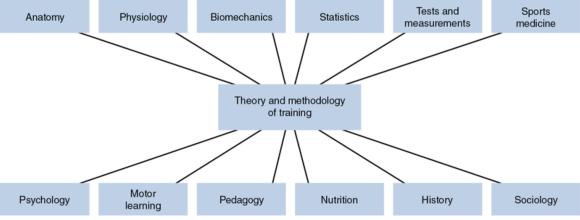

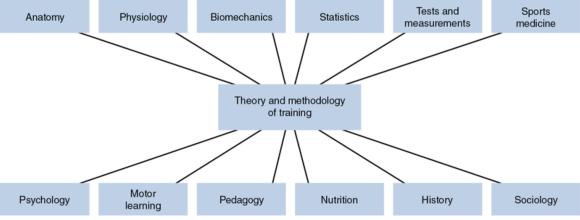

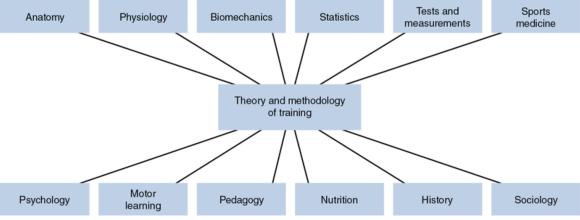

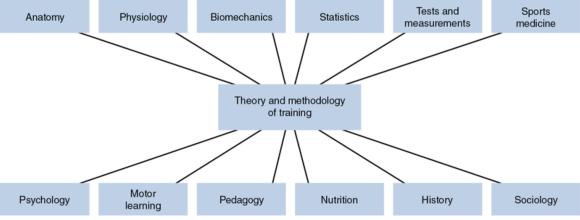

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible. The ability of a coach to direct the optimization of performance is achieved through the development of systematic training plans that draw upon knowledge garnered from a vast array of scientific disciplines, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Auxiliary sciences.

The process of training targets the development of specific attributes correlated with the execution of various tasks. These specific attributes include multilateral physical development, sport-specific physical development, technical skills, tactical abilities, psychological characteristics, health maintenance, injury resistance, and theoretical knowledge. The successful acquisition of these attributes is based upon utilizing means and methods that are individualized and appropriate for the athletes' age, experience, and talent level.

- Multilateral physical development: Multilateral development, or general fitness as it is also known, provides the training foundation for success in all sports. This type of development targets the improvement of the basic biomotor abilities, such as endurance, strength, speed, flexibility, and coordination. Athletes who develop a strong foundation will be able to better tolerate sport-specific training activities and ultimately have a greater potential for athletic development.

- Sport-specific physical development: Sport-specific physical development, or sport-specific fitness as it is sometimes referred to, is the development of physiological or fitness characteristics that are specific to the sport. This type of training may target several specific needs of the sport such as strength, skill, endurance, speed, and flexibility. However, many sports require a blending of key aspects of performance, such as power, muscle endurance, or speed-endurance.

- Technical skills: This training focuses on the development of the technical skills necessary for success in the sporting activity. The ability to perfect technical skills is based upon both multilateral and sport-specific physical development. For example, the ability to perform the iron cross in gymnastics appears to be limited by strength, one of the biomotor abilities. Ultimately the purpose of training that targets the development of technical skills is to perfect technique and allow for the optimization of the sport-specific skills necessary for successful athletic performance. The development of technique should occur under both normal and unusual conditions (e.g., weather, noise, etc.) and should always focus on perfecting the specific skills required by the sport.

- Tactical abilities: The development of tactical abilities is also of particular importance to the training process. Training in this area is designed to improve competitive strategies and is based upon studying the tactics of opponents. Specifically, this type of training is designed to develop strategies that take advantage of the technical and physical capabilities of the athlete so that the chances of success in competition are increased.

- Psychological factors: Psychological preparation is also necessary to ensure the optimization of physical performance. Some authors have also called this type of training personality development training. Regardless of the terminology, the development of psychological characteristics such as discipline, courage, perseverance, and confidence are essential for successful athletic performance.

- Health maintenance: The overall health of the athlete should be considered very important. Proper health can be maintained by periodic medical examinations and appropriate scheduling of training, including alternating between periods of hard work and periods of regeneration or restoration. Injuries and illness require specific attention, and proper management of these occurrences is an important priority to consider during the training process.

- Injury resistance: The best way to prevent injuries is to ensure that the athlete has developed the physical capacity and physiological characteristics necessary to participate in rigorous training and competition and to ensure appropriate application of training. The inappropriate application of training, which includes excessive loading, will increase the risk of injury. With young athletes it is crucial that multilateral physical development is targeted, as this allows for the development of biomotor abilities that will help decrease the potential for injury. Additionally, the management of fatigue appears to be of particular importance. When fatigue is high, the occurrence of injuries is markedly increased; therefore, the development of a training plan that manages fatigue should be considered to be of the utmost importance.

- Theoretical knowledge: Training should increase the athletes' knowledge of the physiological and psychological basis of training, planning, nutrition, and regeneration. It is crucial that the athlete understands why certain training activities are being undertaken. This can be accomplished through discussing the training objectives established for each aspect of the training plan or by requiring the athlete to attend seminars and conferences about training. Arming the athlete with theoretical knowledge about the training process and the sport improves the likelihood that the athlete will make good personal decisions and approach the training process with a strong focus, which will allow the coach and athlete to better set training goals.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Consider the individual athlete's needs when developing a training plan

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete’s abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete’s sport, regardless of the performance level.

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete's abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete's sport, regardless of the performance level. Each athlete has physiological and psychological attributes that need to be considered when developing a training plan.

Too often, coaches take an unscientific approach to training by literally following training programs of successful athletes or sport programs with complete disregard for the athlete's training experience, abilities, and physiological makeup. Even worse, some coaches take programs from elite athletes and apply them to junior athletes who have not yet developed the physical literacy, physiological base, or psychological skills needed to undertake these types of programs. Young athletes are not physiologically or psychologically able to tolerate programs created for advanced athletes. The coach needs to understand the athlete's needs and develop training plans that meet those needs. This can be accomplished by following some guidelines.

Plan According to Tolerance Level

The training plan must be based on a comprehensive analysis of the athlete's physiological and psychological parameters, which will give the coach insight into the athlete's work capacity. An individual's training capacity can be determined by the following factors:

- Biological age: The biological age of an athlete is considered a more accurate indicator of the individual's physical performance potential than his chronological age. One of the best indicators of biological age is sexual maturation because it indicates an increase in circulating testosterone levels. Athletes who are more physically mature, as indicated by a higher biological age, appear to be stronger, faster, and better at team sports than their peers who exhibit a lower biological age, even when chronological age is the same. In general children have a greater resistance to fatigue, which may explain why they respond better to higher volumes of training. On the other hand, older adults appear to exhibit a decreased motivation to train intensely, an increased prevalence of injuries, and an increased occurrence of social stressors, all of which may contribute to a decreased ability to tolerate intense training. Most junior athletes tolerate high volumes of training with moderate loads better than high-intensity or high-load training. The combination of heavy loading and high volume is of concern with youth athletes because this practice may increase the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.

- Training age: Training age is defined as the number of years an individual has been preparing for a sporting activity, and it is considerably different than the biological or chronological age. Athletes with a high training age have developed a substantial training base and most likely will be able to participate in a specialized training plan, especially if their early training was multilateral. An athlete who has a high chronological age in conjunction with a low training age may need more multilateral and skill acquisition training because he lacks the training base to allow for a high degree of specialization in his sport.

- Training history: The athlete's training history influences his work capacity. An athlete who has undertaken substantial multilateral training is more likely to have developed her physical potential and readiness for more challenging training, compared with an athlete who has not been trained as well.

- Health status:An athlete who is ill or injured will have a reduced work capacity and often will not be able to tolerate the prescribed training loads. The type of illness or degree of injury and the physiological base converge to determine the training load that the athlete can tolerate. The coach must monitor the athlete's health status to determine an appropriate training load.

- Stress and the recovery rate:The ability to tolerate a training load is often related to all of the stressors that the athlete encounters. Overall stressors are considered additive, and factors that place a high demand on the athlete can alter his ability to tolerate a training load. For example, heavy involvement in school, work, or family activities can affect the athlete's ability to tolerate a training load. Travel to and from work, school, or training can further contribute to stress levels. Coaches should consider these factors and adjust the training load accordingly. For example, during times of high stress, such as academic examinations, a reduction in training load may be warranted.

The age and skill level of an athlete, along with other factors, must be taken into consideration when planning training and practice sessions.

Individualize the Training Load

The ability to adapt to a training load depends on the individual's capacity. As outlined in the preceding section, many factors contribute to the individualized response to training loads and progressions: the athlete's training history, health status, life stress, chronological age, biological age, and training age. Simply mimicking the training plans of elite athletes will not result in high levels of performance. Rather, the coach must address the athlete's needs and capacities by developing an individualized program; this requires detailed observations of the athlete's technical and tactical abilities, physical characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses. As will be discussed later in this chapter, in the section about training models, periodic testing of the athlete will allow for more specific and individualized training plans to be developed. If athletes are roughly at the same level of development and stage of training, less individualization of the training plan may be needed.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Link training periods with a transition phase

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan.

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan. The transition phase serves an important role in preparing the athlete for the next training cycle. The athlete should start the new preparatory phase only when fully recovered from the previous competitive season. If the athlete initiates a new preparatory phase without full recovery, it is likely that performances will be impaired in future competitive cycles and the risk of injury will increase.

The transition phase, often inappropriately called the off-season, links two annual training plans. This phase facilitates psychological rest, relaxation, and biological regeneration while maintaining an acceptable level of general physical preparation (40% to 50% of the competitive phase). Training should be low key: All loading factors should be reduced; the main training components should be centered on general training, with minimal, if any, technical or tactical development. The transition phase generally should last 2 to 4 weeks but could be extended to 6 weeks, especially for younger athletes. Under normal circumstances the transition phase should not last longer than 6 weeks.

There are two common approaches to the transition phase. The first (incorrect) approach encourages complete rest with no physical activity; in this case, the term off-season fits perfectly. This abrupt interruption of training and the complete inactivity can lead to significant detraining even if only undertaken for a short period of time (

Some authors have suggested that an abrupt cessation of training by highly trained athletes creates a phenomenon known as detraining syndrome, relaxation syndrome, exercise abstinence, or exercise dependency syndrome. This type of detraining appears to occur in athletes who either intentionally cease training or are forced to stop training in response to an injury. Detraining syndrome can be characterized by many symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, depression, alterations to cardiovascular function, and a loss of appetite (see the sidebar, Potential Symptoms of Detraining Syndrome, for additional symptoms). These symptoms usually are not pathological and can be reversed if training is resumed within a short time. If the cessation of training is prolonged, these symptoms can become more pronounced, indicating that the athlete's body is unable to adapt to this sudden inactivity. The time frame in which these symptoms manifest themselves is highly specific to the individual athlete; generally, it can occur within 2 to 3 weeks of inactivity and varies in severity.

Simply decreasing the level of training can also stimulate a detraining effect that will decrease physiological (table 8.2) and performance capacity. The magnitude of the detraining effects will be related to the duration of the detraining period. Short-term detraining, which occurs in less than 4 weeks, can result in some significant decreases in endurance and strength performance.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Understand the objectives of training

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible.

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible. The ability of a coach to direct the optimization of performance is achieved through the development of systematic training plans that draw upon knowledge garnered from a vast array of scientific disciplines, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Auxiliary sciences.

The process of training targets the development of specific attributes correlated with the execution of various tasks. These specific attributes include multilateral physical development, sport-specific physical development, technical skills, tactical abilities, psychological characteristics, health maintenance, injury resistance, and theoretical knowledge. The successful acquisition of these attributes is based upon utilizing means and methods that are individualized and appropriate for the athletes' age, experience, and talent level.

- Multilateral physical development: Multilateral development, or general fitness as it is also known, provides the training foundation for success in all sports. This type of development targets the improvement of the basic biomotor abilities, such as endurance, strength, speed, flexibility, and coordination. Athletes who develop a strong foundation will be able to better tolerate sport-specific training activities and ultimately have a greater potential for athletic development.

- Sport-specific physical development: Sport-specific physical development, or sport-specific fitness as it is sometimes referred to, is the development of physiological or fitness characteristics that are specific to the sport. This type of training may target several specific needs of the sport such as strength, skill, endurance, speed, and flexibility. However, many sports require a blending of key aspects of performance, such as power, muscle endurance, or speed-endurance.

- Technical skills: This training focuses on the development of the technical skills necessary for success in the sporting activity. The ability to perfect technical skills is based upon both multilateral and sport-specific physical development. For example, the ability to perform the iron cross in gymnastics appears to be limited by strength, one of the biomotor abilities. Ultimately the purpose of training that targets the development of technical skills is to perfect technique and allow for the optimization of the sport-specific skills necessary for successful athletic performance. The development of technique should occur under both normal and unusual conditions (e.g., weather, noise, etc.) and should always focus on perfecting the specific skills required by the sport.

- Tactical abilities: The development of tactical abilities is also of particular importance to the training process. Training in this area is designed to improve competitive strategies and is based upon studying the tactics of opponents. Specifically, this type of training is designed to develop strategies that take advantage of the technical and physical capabilities of the athlete so that the chances of success in competition are increased.

- Psychological factors: Psychological preparation is also necessary to ensure the optimization of physical performance. Some authors have also called this type of training personality development training. Regardless of the terminology, the development of psychological characteristics such as discipline, courage, perseverance, and confidence are essential for successful athletic performance.

- Health maintenance: The overall health of the athlete should be considered very important. Proper health can be maintained by periodic medical examinations and appropriate scheduling of training, including alternating between periods of hard work and periods of regeneration or restoration. Injuries and illness require specific attention, and proper management of these occurrences is an important priority to consider during the training process.

- Injury resistance: The best way to prevent injuries is to ensure that the athlete has developed the physical capacity and physiological characteristics necessary to participate in rigorous training and competition and to ensure appropriate application of training. The inappropriate application of training, which includes excessive loading, will increase the risk of injury. With young athletes it is crucial that multilateral physical development is targeted, as this allows for the development of biomotor abilities that will help decrease the potential for injury. Additionally, the management of fatigue appears to be of particular importance. When fatigue is high, the occurrence of injuries is markedly increased; therefore, the development of a training plan that manages fatigue should be considered to be of the utmost importance.

- Theoretical knowledge: Training should increase the athletes' knowledge of the physiological and psychological basis of training, planning, nutrition, and regeneration. It is crucial that the athlete understands why certain training activities are being undertaken. This can be accomplished through discussing the training objectives established for each aspect of the training plan or by requiring the athlete to attend seminars and conferences about training. Arming the athlete with theoretical knowledge about the training process and the sport improves the likelihood that the athlete will make good personal decisions and approach the training process with a strong focus, which will allow the coach and athlete to better set training goals.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Consider the individual athlete's needs when developing a training plan

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete’s abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete’s sport, regardless of the performance level.

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete's abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete's sport, regardless of the performance level. Each athlete has physiological and psychological attributes that need to be considered when developing a training plan.

Too often, coaches take an unscientific approach to training by literally following training programs of successful athletes or sport programs with complete disregard for the athlete's training experience, abilities, and physiological makeup. Even worse, some coaches take programs from elite athletes and apply them to junior athletes who have not yet developed the physical literacy, physiological base, or psychological skills needed to undertake these types of programs. Young athletes are not physiologically or psychologically able to tolerate programs created for advanced athletes. The coach needs to understand the athlete's needs and develop training plans that meet those needs. This can be accomplished by following some guidelines.

Plan According to Tolerance Level

The training plan must be based on a comprehensive analysis of the athlete's physiological and psychological parameters, which will give the coach insight into the athlete's work capacity. An individual's training capacity can be determined by the following factors:

- Biological age: The biological age of an athlete is considered a more accurate indicator of the individual's physical performance potential than his chronological age. One of the best indicators of biological age is sexual maturation because it indicates an increase in circulating testosterone levels. Athletes who are more physically mature, as indicated by a higher biological age, appear to be stronger, faster, and better at team sports than their peers who exhibit a lower biological age, even when chronological age is the same. In general children have a greater resistance to fatigue, which may explain why they respond better to higher volumes of training. On the other hand, older adults appear to exhibit a decreased motivation to train intensely, an increased prevalence of injuries, and an increased occurrence of social stressors, all of which may contribute to a decreased ability to tolerate intense training. Most junior athletes tolerate high volumes of training with moderate loads better than high-intensity or high-load training. The combination of heavy loading and high volume is of concern with youth athletes because this practice may increase the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.

- Training age: Training age is defined as the number of years an individual has been preparing for a sporting activity, and it is considerably different than the biological or chronological age. Athletes with a high training age have developed a substantial training base and most likely will be able to participate in a specialized training plan, especially if their early training was multilateral. An athlete who has a high chronological age in conjunction with a low training age may need more multilateral and skill acquisition training because he lacks the training base to allow for a high degree of specialization in his sport.

- Training history: The athlete's training history influences his work capacity. An athlete who has undertaken substantial multilateral training is more likely to have developed her physical potential and readiness for more challenging training, compared with an athlete who has not been trained as well.

- Health status:An athlete who is ill or injured will have a reduced work capacity and often will not be able to tolerate the prescribed training loads. The type of illness or degree of injury and the physiological base converge to determine the training load that the athlete can tolerate. The coach must monitor the athlete's health status to determine an appropriate training load.

- Stress and the recovery rate:The ability to tolerate a training load is often related to all of the stressors that the athlete encounters. Overall stressors are considered additive, and factors that place a high demand on the athlete can alter his ability to tolerate a training load. For example, heavy involvement in school, work, or family activities can affect the athlete's ability to tolerate a training load. Travel to and from work, school, or training can further contribute to stress levels. Coaches should consider these factors and adjust the training load accordingly. For example, during times of high stress, such as academic examinations, a reduction in training load may be warranted.

The age and skill level of an athlete, along with other factors, must be taken into consideration when planning training and practice sessions.

Individualize the Training Load

The ability to adapt to a training load depends on the individual's capacity. As outlined in the preceding section, many factors contribute to the individualized response to training loads and progressions: the athlete's training history, health status, life stress, chronological age, biological age, and training age. Simply mimicking the training plans of elite athletes will not result in high levels of performance. Rather, the coach must address the athlete's needs and capacities by developing an individualized program; this requires detailed observations of the athlete's technical and tactical abilities, physical characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses. As will be discussed later in this chapter, in the section about training models, periodic testing of the athlete will allow for more specific and individualized training plans to be developed. If athletes are roughly at the same level of development and stage of training, less individualization of the training plan may be needed.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Link training periods with a transition phase

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan.

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan. The transition phase serves an important role in preparing the athlete for the next training cycle. The athlete should start the new preparatory phase only when fully recovered from the previous competitive season. If the athlete initiates a new preparatory phase without full recovery, it is likely that performances will be impaired in future competitive cycles and the risk of injury will increase.

The transition phase, often inappropriately called the off-season, links two annual training plans. This phase facilitates psychological rest, relaxation, and biological regeneration while maintaining an acceptable level of general physical preparation (40% to 50% of the competitive phase). Training should be low key: All loading factors should be reduced; the main training components should be centered on general training, with minimal, if any, technical or tactical development. The transition phase generally should last 2 to 4 weeks but could be extended to 6 weeks, especially for younger athletes. Under normal circumstances the transition phase should not last longer than 6 weeks.

There are two common approaches to the transition phase. The first (incorrect) approach encourages complete rest with no physical activity; in this case, the term off-season fits perfectly. This abrupt interruption of training and the complete inactivity can lead to significant detraining even if only undertaken for a short period of time (

Some authors have suggested that an abrupt cessation of training by highly trained athletes creates a phenomenon known as detraining syndrome, relaxation syndrome, exercise abstinence, or exercise dependency syndrome. This type of detraining appears to occur in athletes who either intentionally cease training or are forced to stop training in response to an injury. Detraining syndrome can be characterized by many symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, depression, alterations to cardiovascular function, and a loss of appetite (see the sidebar, Potential Symptoms of Detraining Syndrome, for additional symptoms). These symptoms usually are not pathological and can be reversed if training is resumed within a short time. If the cessation of training is prolonged, these symptoms can become more pronounced, indicating that the athlete's body is unable to adapt to this sudden inactivity. The time frame in which these symptoms manifest themselves is highly specific to the individual athlete; generally, it can occur within 2 to 3 weeks of inactivity and varies in severity.

Simply decreasing the level of training can also stimulate a detraining effect that will decrease physiological (table 8.2) and performance capacity. The magnitude of the detraining effects will be related to the duration of the detraining period. Short-term detraining, which occurs in less than 4 weeks, can result in some significant decreases in endurance and strength performance.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Understand the objectives of training

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible.

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible. The ability of a coach to direct the optimization of performance is achieved through the development of systematic training plans that draw upon knowledge garnered from a vast array of scientific disciplines, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Auxiliary sciences.

The process of training targets the development of specific attributes correlated with the execution of various tasks. These specific attributes include multilateral physical development, sport-specific physical development, technical skills, tactical abilities, psychological characteristics, health maintenance, injury resistance, and theoretical knowledge. The successful acquisition of these attributes is based upon utilizing means and methods that are individualized and appropriate for the athletes' age, experience, and talent level.

- Multilateral physical development: Multilateral development, or general fitness as it is also known, provides the training foundation for success in all sports. This type of development targets the improvement of the basic biomotor abilities, such as endurance, strength, speed, flexibility, and coordination. Athletes who develop a strong foundation will be able to better tolerate sport-specific training activities and ultimately have a greater potential for athletic development.

- Sport-specific physical development: Sport-specific physical development, or sport-specific fitness as it is sometimes referred to, is the development of physiological or fitness characteristics that are specific to the sport. This type of training may target several specific needs of the sport such as strength, skill, endurance, speed, and flexibility. However, many sports require a blending of key aspects of performance, such as power, muscle endurance, or speed-endurance.

- Technical skills: This training focuses on the development of the technical skills necessary for success in the sporting activity. The ability to perfect technical skills is based upon both multilateral and sport-specific physical development. For example, the ability to perform the iron cross in gymnastics appears to be limited by strength, one of the biomotor abilities. Ultimately the purpose of training that targets the development of technical skills is to perfect technique and allow for the optimization of the sport-specific skills necessary for successful athletic performance. The development of technique should occur under both normal and unusual conditions (e.g., weather, noise, etc.) and should always focus on perfecting the specific skills required by the sport.

- Tactical abilities: The development of tactical abilities is also of particular importance to the training process. Training in this area is designed to improve competitive strategies and is based upon studying the tactics of opponents. Specifically, this type of training is designed to develop strategies that take advantage of the technical and physical capabilities of the athlete so that the chances of success in competition are increased.

- Psychological factors: Psychological preparation is also necessary to ensure the optimization of physical performance. Some authors have also called this type of training personality development training. Regardless of the terminology, the development of psychological characteristics such as discipline, courage, perseverance, and confidence are essential for successful athletic performance.

- Health maintenance: The overall health of the athlete should be considered very important. Proper health can be maintained by periodic medical examinations and appropriate scheduling of training, including alternating between periods of hard work and periods of regeneration or restoration. Injuries and illness require specific attention, and proper management of these occurrences is an important priority to consider during the training process.

- Injury resistance: The best way to prevent injuries is to ensure that the athlete has developed the physical capacity and physiological characteristics necessary to participate in rigorous training and competition and to ensure appropriate application of training. The inappropriate application of training, which includes excessive loading, will increase the risk of injury. With young athletes it is crucial that multilateral physical development is targeted, as this allows for the development of biomotor abilities that will help decrease the potential for injury. Additionally, the management of fatigue appears to be of particular importance. When fatigue is high, the occurrence of injuries is markedly increased; therefore, the development of a training plan that manages fatigue should be considered to be of the utmost importance.

- Theoretical knowledge: Training should increase the athletes' knowledge of the physiological and psychological basis of training, planning, nutrition, and regeneration. It is crucial that the athlete understands why certain training activities are being undertaken. This can be accomplished through discussing the training objectives established for each aspect of the training plan or by requiring the athlete to attend seminars and conferences about training. Arming the athlete with theoretical knowledge about the training process and the sport improves the likelihood that the athlete will make good personal decisions and approach the training process with a strong focus, which will allow the coach and athlete to better set training goals.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Consider the individual athlete's needs when developing a training plan

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete’s abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete’s sport, regardless of the performance level.

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete's abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete's sport, regardless of the performance level. Each athlete has physiological and psychological attributes that need to be considered when developing a training plan.

Too often, coaches take an unscientific approach to training by literally following training programs of successful athletes or sport programs with complete disregard for the athlete's training experience, abilities, and physiological makeup. Even worse, some coaches take programs from elite athletes and apply them to junior athletes who have not yet developed the physical literacy, physiological base, or psychological skills needed to undertake these types of programs. Young athletes are not physiologically or psychologically able to tolerate programs created for advanced athletes. The coach needs to understand the athlete's needs and develop training plans that meet those needs. This can be accomplished by following some guidelines.

Plan According to Tolerance Level

The training plan must be based on a comprehensive analysis of the athlete's physiological and psychological parameters, which will give the coach insight into the athlete's work capacity. An individual's training capacity can be determined by the following factors:

- Biological age: The biological age of an athlete is considered a more accurate indicator of the individual's physical performance potential than his chronological age. One of the best indicators of biological age is sexual maturation because it indicates an increase in circulating testosterone levels. Athletes who are more physically mature, as indicated by a higher biological age, appear to be stronger, faster, and better at team sports than their peers who exhibit a lower biological age, even when chronological age is the same. In general children have a greater resistance to fatigue, which may explain why they respond better to higher volumes of training. On the other hand, older adults appear to exhibit a decreased motivation to train intensely, an increased prevalence of injuries, and an increased occurrence of social stressors, all of which may contribute to a decreased ability to tolerate intense training. Most junior athletes tolerate high volumes of training with moderate loads better than high-intensity or high-load training. The combination of heavy loading and high volume is of concern with youth athletes because this practice may increase the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.

- Training age: Training age is defined as the number of years an individual has been preparing for a sporting activity, and it is considerably different than the biological or chronological age. Athletes with a high training age have developed a substantial training base and most likely will be able to participate in a specialized training plan, especially if their early training was multilateral. An athlete who has a high chronological age in conjunction with a low training age may need more multilateral and skill acquisition training because he lacks the training base to allow for a high degree of specialization in his sport.

- Training history: The athlete's training history influences his work capacity. An athlete who has undertaken substantial multilateral training is more likely to have developed her physical potential and readiness for more challenging training, compared with an athlete who has not been trained as well.

- Health status:An athlete who is ill or injured will have a reduced work capacity and often will not be able to tolerate the prescribed training loads. The type of illness or degree of injury and the physiological base converge to determine the training load that the athlete can tolerate. The coach must monitor the athlete's health status to determine an appropriate training load.

- Stress and the recovery rate:The ability to tolerate a training load is often related to all of the stressors that the athlete encounters. Overall stressors are considered additive, and factors that place a high demand on the athlete can alter his ability to tolerate a training load. For example, heavy involvement in school, work, or family activities can affect the athlete's ability to tolerate a training load. Travel to and from work, school, or training can further contribute to stress levels. Coaches should consider these factors and adjust the training load accordingly. For example, during times of high stress, such as academic examinations, a reduction in training load may be warranted.

The age and skill level of an athlete, along with other factors, must be taken into consideration when planning training and practice sessions.

Individualize the Training Load

The ability to adapt to a training load depends on the individual's capacity. As outlined in the preceding section, many factors contribute to the individualized response to training loads and progressions: the athlete's training history, health status, life stress, chronological age, biological age, and training age. Simply mimicking the training plans of elite athletes will not result in high levels of performance. Rather, the coach must address the athlete's needs and capacities by developing an individualized program; this requires detailed observations of the athlete's technical and tactical abilities, physical characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses. As will be discussed later in this chapter, in the section about training models, periodic testing of the athlete will allow for more specific and individualized training plans to be developed. If athletes are roughly at the same level of development and stage of training, less individualization of the training plan may be needed.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Link training periods with a transition phase

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan.

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan. The transition phase serves an important role in preparing the athlete for the next training cycle. The athlete should start the new preparatory phase only when fully recovered from the previous competitive season. If the athlete initiates a new preparatory phase without full recovery, it is likely that performances will be impaired in future competitive cycles and the risk of injury will increase.

The transition phase, often inappropriately called the off-season, links two annual training plans. This phase facilitates psychological rest, relaxation, and biological regeneration while maintaining an acceptable level of general physical preparation (40% to 50% of the competitive phase). Training should be low key: All loading factors should be reduced; the main training components should be centered on general training, with minimal, if any, technical or tactical development. The transition phase generally should last 2 to 4 weeks but could be extended to 6 weeks, especially for younger athletes. Under normal circumstances the transition phase should not last longer than 6 weeks.

There are two common approaches to the transition phase. The first (incorrect) approach encourages complete rest with no physical activity; in this case, the term off-season fits perfectly. This abrupt interruption of training and the complete inactivity can lead to significant detraining even if only undertaken for a short period of time (

Some authors have suggested that an abrupt cessation of training by highly trained athletes creates a phenomenon known as detraining syndrome, relaxation syndrome, exercise abstinence, or exercise dependency syndrome. This type of detraining appears to occur in athletes who either intentionally cease training or are forced to stop training in response to an injury. Detraining syndrome can be characterized by many symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, depression, alterations to cardiovascular function, and a loss of appetite (see the sidebar, Potential Symptoms of Detraining Syndrome, for additional symptoms). These symptoms usually are not pathological and can be reversed if training is resumed within a short time. If the cessation of training is prolonged, these symptoms can become more pronounced, indicating that the athlete's body is unable to adapt to this sudden inactivity. The time frame in which these symptoms manifest themselves is highly specific to the individual athlete; generally, it can occur within 2 to 3 weeks of inactivity and varies in severity.

Simply decreasing the level of training can also stimulate a detraining effect that will decrease physiological (table 8.2) and performance capacity. The magnitude of the detraining effects will be related to the duration of the detraining period. Short-term detraining, which occurs in less than 4 weeks, can result in some significant decreases in endurance and strength performance.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Understand the objectives of training

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible.

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible. The ability of a coach to direct the optimization of performance is achieved through the development of systematic training plans that draw upon knowledge garnered from a vast array of scientific disciplines, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Auxiliary sciences.

The process of training targets the development of specific attributes correlated with the execution of various tasks. These specific attributes include multilateral physical development, sport-specific physical development, technical skills, tactical abilities, psychological characteristics, health maintenance, injury resistance, and theoretical knowledge. The successful acquisition of these attributes is based upon utilizing means and methods that are individualized and appropriate for the athletes' age, experience, and talent level.

- Multilateral physical development: Multilateral development, or general fitness as it is also known, provides the training foundation for success in all sports. This type of development targets the improvement of the basic biomotor abilities, such as endurance, strength, speed, flexibility, and coordination. Athletes who develop a strong foundation will be able to better tolerate sport-specific training activities and ultimately have a greater potential for athletic development.

- Sport-specific physical development: Sport-specific physical development, or sport-specific fitness as it is sometimes referred to, is the development of physiological or fitness characteristics that are specific to the sport. This type of training may target several specific needs of the sport such as strength, skill, endurance, speed, and flexibility. However, many sports require a blending of key aspects of performance, such as power, muscle endurance, or speed-endurance.

- Technical skills: This training focuses on the development of the technical skills necessary for success in the sporting activity. The ability to perfect technical skills is based upon both multilateral and sport-specific physical development. For example, the ability to perform the iron cross in gymnastics appears to be limited by strength, one of the biomotor abilities. Ultimately the purpose of training that targets the development of technical skills is to perfect technique and allow for the optimization of the sport-specific skills necessary for successful athletic performance. The development of technique should occur under both normal and unusual conditions (e.g., weather, noise, etc.) and should always focus on perfecting the specific skills required by the sport.

- Tactical abilities: The development of tactical abilities is also of particular importance to the training process. Training in this area is designed to improve competitive strategies and is based upon studying the tactics of opponents. Specifically, this type of training is designed to develop strategies that take advantage of the technical and physical capabilities of the athlete so that the chances of success in competition are increased.

- Psychological factors: Psychological preparation is also necessary to ensure the optimization of physical performance. Some authors have also called this type of training personality development training. Regardless of the terminology, the development of psychological characteristics such as discipline, courage, perseverance, and confidence are essential for successful athletic performance.

- Health maintenance: The overall health of the athlete should be considered very important. Proper health can be maintained by periodic medical examinations and appropriate scheduling of training, including alternating between periods of hard work and periods of regeneration or restoration. Injuries and illness require specific attention, and proper management of these occurrences is an important priority to consider during the training process.

- Injury resistance: The best way to prevent injuries is to ensure that the athlete has developed the physical capacity and physiological characteristics necessary to participate in rigorous training and competition and to ensure appropriate application of training. The inappropriate application of training, which includes excessive loading, will increase the risk of injury. With young athletes it is crucial that multilateral physical development is targeted, as this allows for the development of biomotor abilities that will help decrease the potential for injury. Additionally, the management of fatigue appears to be of particular importance. When fatigue is high, the occurrence of injuries is markedly increased; therefore, the development of a training plan that manages fatigue should be considered to be of the utmost importance.

- Theoretical knowledge: Training should increase the athletes' knowledge of the physiological and psychological basis of training, planning, nutrition, and regeneration. It is crucial that the athlete understands why certain training activities are being undertaken. This can be accomplished through discussing the training objectives established for each aspect of the training plan or by requiring the athlete to attend seminars and conferences about training. Arming the athlete with theoretical knowledge about the training process and the sport improves the likelihood that the athlete will make good personal decisions and approach the training process with a strong focus, which will allow the coach and athlete to better set training goals.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Consider the individual athlete's needs when developing a training plan

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete’s abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete’s sport, regardless of the performance level.

Individualization is one of the main requirements of contemporary training. Individualization requires that the coach consider the athlete's abilities, potential, and learning characteristics and the demands of the athlete's sport, regardless of the performance level. Each athlete has physiological and psychological attributes that need to be considered when developing a training plan.

Too often, coaches take an unscientific approach to training by literally following training programs of successful athletes or sport programs with complete disregard for the athlete's training experience, abilities, and physiological makeup. Even worse, some coaches take programs from elite athletes and apply them to junior athletes who have not yet developed the physical literacy, physiological base, or psychological skills needed to undertake these types of programs. Young athletes are not physiologically or psychologically able to tolerate programs created for advanced athletes. The coach needs to understand the athlete's needs and develop training plans that meet those needs. This can be accomplished by following some guidelines.

Plan According to Tolerance Level

The training plan must be based on a comprehensive analysis of the athlete's physiological and psychological parameters, which will give the coach insight into the athlete's work capacity. An individual's training capacity can be determined by the following factors:

- Biological age: The biological age of an athlete is considered a more accurate indicator of the individual's physical performance potential than his chronological age. One of the best indicators of biological age is sexual maturation because it indicates an increase in circulating testosterone levels. Athletes who are more physically mature, as indicated by a higher biological age, appear to be stronger, faster, and better at team sports than their peers who exhibit a lower biological age, even when chronological age is the same. In general children have a greater resistance to fatigue, which may explain why they respond better to higher volumes of training. On the other hand, older adults appear to exhibit a decreased motivation to train intensely, an increased prevalence of injuries, and an increased occurrence of social stressors, all of which may contribute to a decreased ability to tolerate intense training. Most junior athletes tolerate high volumes of training with moderate loads better than high-intensity or high-load training. The combination of heavy loading and high volume is of concern with youth athletes because this practice may increase the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.

- Training age: Training age is defined as the number of years an individual has been preparing for a sporting activity, and it is considerably different than the biological or chronological age. Athletes with a high training age have developed a substantial training base and most likely will be able to participate in a specialized training plan, especially if their early training was multilateral. An athlete who has a high chronological age in conjunction with a low training age may need more multilateral and skill acquisition training because he lacks the training base to allow for a high degree of specialization in his sport.

- Training history: The athlete's training history influences his work capacity. An athlete who has undertaken substantial multilateral training is more likely to have developed her physical potential and readiness for more challenging training, compared with an athlete who has not been trained as well.

- Health status:An athlete who is ill or injured will have a reduced work capacity and often will not be able to tolerate the prescribed training loads. The type of illness or degree of injury and the physiological base converge to determine the training load that the athlete can tolerate. The coach must monitor the athlete's health status to determine an appropriate training load.

- Stress and the recovery rate:The ability to tolerate a training load is often related to all of the stressors that the athlete encounters. Overall stressors are considered additive, and factors that place a high demand on the athlete can alter his ability to tolerate a training load. For example, heavy involvement in school, work, or family activities can affect the athlete's ability to tolerate a training load. Travel to and from work, school, or training can further contribute to stress levels. Coaches should consider these factors and adjust the training load accordingly. For example, during times of high stress, such as academic examinations, a reduction in training load may be warranted.

The age and skill level of an athlete, along with other factors, must be taken into consideration when planning training and practice sessions.

Individualize the Training Load

The ability to adapt to a training load depends on the individual's capacity. As outlined in the preceding section, many factors contribute to the individualized response to training loads and progressions: the athlete's training history, health status, life stress, chronological age, biological age, and training age. Simply mimicking the training plans of elite athletes will not result in high levels of performance. Rather, the coach must address the athlete's needs and capacities by developing an individualized program; this requires detailed observations of the athlete's technical and tactical abilities, physical characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses. As will be discussed later in this chapter, in the section about training models, periodic testing of the athlete will allow for more specific and individualized training plans to be developed. If athletes are roughly at the same level of development and stage of training, less individualization of the training plan may be needed.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Link training periods with a transition phase

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan.

After long periods of training, hard work, and stressful competitions in which both physiological and psychological fatigue can accumulate, a transition period should be used to link annual training plans or preparation for another major competition, as in the case of the bi-cycle, tri-cycle, and multicycle annual training plan. The transition phase serves an important role in preparing the athlete for the next training cycle. The athlete should start the new preparatory phase only when fully recovered from the previous competitive season. If the athlete initiates a new preparatory phase without full recovery, it is likely that performances will be impaired in future competitive cycles and the risk of injury will increase.

The transition phase, often inappropriately called the off-season, links two annual training plans. This phase facilitates psychological rest, relaxation, and biological regeneration while maintaining an acceptable level of general physical preparation (40% to 50% of the competitive phase). Training should be low key: All loading factors should be reduced; the main training components should be centered on general training, with minimal, if any, technical or tactical development. The transition phase generally should last 2 to 4 weeks but could be extended to 6 weeks, especially for younger athletes. Under normal circumstances the transition phase should not last longer than 6 weeks.

There are two common approaches to the transition phase. The first (incorrect) approach encourages complete rest with no physical activity; in this case, the term off-season fits perfectly. This abrupt interruption of training and the complete inactivity can lead to significant detraining even if only undertaken for a short period of time (

Some authors have suggested that an abrupt cessation of training by highly trained athletes creates a phenomenon known as detraining syndrome, relaxation syndrome, exercise abstinence, or exercise dependency syndrome. This type of detraining appears to occur in athletes who either intentionally cease training or are forced to stop training in response to an injury. Detraining syndrome can be characterized by many symptoms including insomnia, anxiety, depression, alterations to cardiovascular function, and a loss of appetite (see the sidebar, Potential Symptoms of Detraining Syndrome, for additional symptoms). These symptoms usually are not pathological and can be reversed if training is resumed within a short time. If the cessation of training is prolonged, these symptoms can become more pronounced, indicating that the athlete's body is unable to adapt to this sudden inactivity. The time frame in which these symptoms manifest themselves is highly specific to the individual athlete; generally, it can occur within 2 to 3 weeks of inactivity and varies in severity.

Simply decreasing the level of training can also stimulate a detraining effect that will decrease physiological (table 8.2) and performance capacity. The magnitude of the detraining effects will be related to the duration of the detraining period. Short-term detraining, which occurs in less than 4 weeks, can result in some significant decreases in endurance and strength performance.

Learn more about Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Sixth Edition.

Understand the objectives of training

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible.

Training is a process by which an athlete is prepared for the highest level of performance possible. The ability of a coach to direct the optimization of performance is achieved through the development of systematic training plans that draw upon knowledge garnered from a vast array of scientific disciplines, as shown in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Auxiliary sciences.

The process of training targets the development of specific attributes correlated with the execution of various tasks. These specific attributes include multilateral physical development, sport-specific physical development, technical skills, tactical abilities, psychological characteristics, health maintenance, injury resistance, and theoretical knowledge. The successful acquisition of these attributes is based upon utilizing means and methods that are individualized and appropriate for the athletes' age, experience, and talent level.

- Multilateral physical development: Multilateral development, or general fitness as it is also known, provides the training foundation for success in all sports. This type of development targets the improvement of the basic biomotor abilities, such as endurance, strength, speed, flexibility, and coordination. Athletes who develop a strong foundation will be able to better tolerate sport-specific training activities and ultimately have a greater potential for athletic development.

- Sport-specific physical development: Sport-specific physical development, or sport-specific fitness as it is sometimes referred to, is the development of physiological or fitness characteristics that are specific to the sport. This type of training may target several specific needs of the sport such as strength, skill, endurance, speed, and flexibility. However, many sports require a blending of key aspects of performance, such as power, muscle endurance, or speed-endurance.

- Technical skills: This training focuses on the development of the technical skills necessary for success in the sporting activity. The ability to perfect technical skills is based upon both multilateral and sport-specific physical development. For example, the ability to perform the iron cross in gymnastics appears to be limited by strength, one of the biomotor abilities. Ultimately the purpose of training that targets the development of technical skills is to perfect technique and allow for the optimization of the sport-specific skills necessary for successful athletic performance. The development of technique should occur under both normal and unusual conditions (e.g., weather, noise, etc.) and should always focus on perfecting the specific skills required by the sport.

- Tactical abilities: The development of tactical abilities is also of particular importance to the training process. Training in this area is designed to improve competitive strategies and is based upon studying the tactics of opponents. Specifically, this type of training is designed to develop strategies that take advantage of the technical and physical capabilities of the athlete so that the chances of success in competition are increased.

- Psychological factors: Psychological preparation is also necessary to ensure the optimization of physical performance. Some authors have also called this type of training personality development training. Regardless of the terminology, the development of psychological characteristics such as discipline, courage, perseverance, and confidence are essential for successful athletic performance.