- Home

- Sport Management and Sport Business

- Research Methods, Measurements, and Evaluation

- Research Methods and Design in Sport Management

Research Methods and Design in Sport Management

by Damon P.S. Andrew, Paul M. Pedersen and Chad D. McEvoy

376 Pages

An invaluable resource for both students and practitioners, the text first helps readers understand the research process and then delves into specific research methods. Special attention is devoted to the process of reading and understanding research in the field, preparing readers to apply the concepts long after reading the text and learning the foundational skills:

- How to conduct a thorough literature review

- Theoretical and conceptual frameworks to guide the research process

- How to develop appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Techniques for conducting qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research

- Methods for analyzing data and reporting results

To ensure readers can effectively apply the research concepts presented, practical examples of past research by leading sport management scholars are incorporated throughout the text. At the conclusion of each chapter, a Research Methods and Design in Action feature presents excerpts from the Journal of Sport Management to serve as case study examples with noteworthy descriptions of the employed research methods. Each journal article is then featured in its entirety in the new companion web resource, along with discussion questions that may serve as additional learning activities to guide students through challenging concepts.

Research Methods and Design in Sport Management, Second Edition, presents the tools to engage in the broad spectrum of research opportunities in sport management. With the help of this book, readers will ensure that they properly collect, analyze, and share research to inform strategic business decisions.

Chapter 1. Research Concepts in Sport Management

Research Defined

Types of Research

Research Traditions

The Evolution of Sport Management Research

Summary

Chapter 2. Ethical Issues in Research

Protection of Human Subjects

Ethical Principles and Guidelines

Institutional Review Board

Informed Consent

Scientific Dishonesty

Summary

Part II. The Research Process

Chapter 3. Creation of Research Questions

Problem Selection

Literature Review

Development of a Conceptual Framework

Focusing of Research Questions

Identification of Variables

Clarification of Hypotheses

Summary

Chapter 4. Research Design

Types of Research Design

Sampling

Determination of Sample Size

Reliability

Validity

Summary

Chapter 5. Data Collection and Analysis

Nonresponse Bias

Preparation of Data for Analysis

Scales of Measurement

Descriptive Statistics

Inferential Statistics

Statistical Design

Drawing Conclusions

Summary

Chapter 6. Dissemination of Findings

Academic Conference Presentation

Academic Journal Selection

Manuscript Structure

Journal Publication Process

Evaluation of Journal Articles

Summary

Part III. Research Design in Sport Management

Chapter 7. Surveys

Interviews

Questionnaires

Internet Surveys

Questionnaire Development and Design

Types of Error

Summary

Chapter 8. Interviews

Interview Techniques

Interview Process

Data Analysis

Summary

Chapter 9. Observation Research

Methodological Foundations

Observation Site

Observer Roles

Autoethnography in Sport Management

Online Observation in Sport Management

Data Collection

Field Notes

Data Analysis

Summary

Chapter 10. Case Study Research

Applied Research Advantages

Defining Sport Management Case Study Research

Research Versus Teaching Case Studies

Design and Implementation

Research Preparation

Data Collection

Data Analysis

Case Study Report

Summary

Chapter 11. Historical Research

Academic Perspective

Practical Applications

Research Prerequisites

Topic Selection

Source Material

Data Analysis

Historical Writing

Summary

Chapter 12. Legal Research

Qualities of Legal Research

Nature of the Law and Legal Research

Legal Research Techniques

Sources of Legal Information

Design and Implementation

Summary

Part IV. Statistical Methods in Sport Management

Chapter 13. Analyses of Structure

Importance of Reliability and Validity

Cronbach’s Alpha

Exploratory Factor Analysis and Principal Component Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Summary

Chapter 14. Relationships Between Variables

Bivariate Correlation

Simple Linear Regression

Multiple Regression

Path Analysis

Summary

Chapter 15. Significance of Group Differences

T-Test

One-Way ANOVA

One-Way ANCOVA

Factorial ANOVA

Factorial ANCOVA

One-Way MANOVA

One-Way MANCOVA

Factorial MANOVA

Factorial MANCOVA

Summary

Chapter 16. Prediction of Group Membership

Discriminant Analysis

Logistic Regression

Cluster Analysis

Summary

Part V. Emerging Methods and Trends in Sport Management Research

Chapter 17. Social Network Analysis in Sport

Background and History of Social Network Analysis

Social Network Analysis in Sport

Collecting Social Network Data

Analyzing Social Network Data

Strengths and Limitations of Social Network Analysis

Future Directions for Social Network Analysis in Sport

Summary

Chapter 18. Sport Analytics

Defining Sport Analytics and Its Process

Analytical Techniques and Metrics in Sport

Team and Player Performance Metrics

Sport Business Metrics

Sport Analytics Process Examples

Summary

Damon Andrew, PhD, serves as dean and professor in the College of Education at Florida State University. He earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education and a master’s degree in exercise physiology from the University of South Alabama, two additional master’s degrees in biomechanics and sport management from the University of Florida, and a PhD in sport management from Florida State University. In addition, he completed postgraduate certificates in higher education administration from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education and Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development.

Andrew’s research has been supported by over $2.5 million in funding via 29 grants and contracts; it includes over 150 peer-reviewed articles, reviews, proceedings, and book chapters, and more than 100 presentations at national and international conferences. He has been elected to serve as president and member-at-large for the North American Society for Sport Management; as financial officer for the Sport and Recreation Law Association; and as vice chair, chair-elect, and board chair of the American Association of University Administrators. He is currently the senior editor of the Journal of Higher Education Management and associate editor of the International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, as well as a previous editor of both Sport Management Education Journal and Journal of Applied Sport Management. His scholarship has been recognized with the Applied Sport Management Association Scholar Lifetime Achievement Award, the National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education Scholar Award, the Society of Health and Physical Educators Southern District Scholar Award, and the Society of Health and Physical Educators Mabel Lee Award. He is the only sport management scholar to ever be elected as a fellow of both the National Academy of Kinesiology and the National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education.

Andrew directed University of Louisville’s doctoral program in sport administration from 2004 to 2006, founded and directed a doctoral program in sport management at the University of Tennessee from 2006 to 2008, and then served at Troy University as the dean of the College of Health and Human Services from 2008 to 2013 and as dean of the College of Human Sciences and Education from 2013 to 2018. He has been named a distinguished alumnus of the University of South Alabama, the University of Florida, and Florida State University, and his administrative efforts have been recognized nationally by the American Association of University Administrators, the National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education, and the Southern District of the Society of Health and Physical Educators.

Paul M. Pedersen, PhD, is a professor of sport management in the School of Public Health at Indiana University at Bloomington (IU). In addition to teaching undergraduate and graduate courses at IU, Pedersen has been the doctoral chair of 19 PhD graduates and a committee member of another 22 dissertations. As an extension of his previous work as a sportswriter and sport business columnist, Pedersen's primary areas of scholarly interest and research are the symbiotic relationship between sport and communication as well as the activities and practices of various sport organization personnel.

A research fellow of the North American Society for Sport Management (NASSM), Pedersen has published eight books (including Contemporary Sport Management, Handbook of Sport Communication, and Strategic Sport Communication) and more than 100 articles in peer-reviewed outlets such as the Journal of Sport Management, European Sport Management Quarterly, Sport Marketing Quarterly, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, Sociology of Sport Journal, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, and Journal of Sports Economics. He has also been a part of more than 100 refereed presentations at professional conferences and more than 50 invited presentations, including invited addresses in China, Denmark, Hungary, Norway, and South Korea. He has been interviewed and quoted in publications as diverse as the New York Times and China Daily.

Founder and editor in chief of the International Journal of Sport Communication, he serves on the editorial board of nine journals. A 2011 inductee into the Golden Eagle Hall of Fame (East High School in Pueblo, Colorado), Pedersen lives in Bloomington, Indiana, with his wife, Jennifer, and their two youngest children, Brock and Carlie. Their two oldest children, Hallie and Zack, graduated from IU.

Chad D. McEvoy, EdD, is a professor and the chair of the sport management program in the kinesiology and physical education department at Northern Illinois University. Before pursuing a career in academia, McEvoy worked in marketing and fundraising in intercollegiate athletics at Iowa State University and Western Michigan University. He has conducted research projects for clients in professional sport, intercollegiate athletics, and Olympic sport and for sport agency organizations.

McEvoy holds a doctoral degree from the University of Northern Colorado, a master’s degree from the University of Massachusetts, and a bachelor’s degree from Iowa State University, each in sport management and administration. His research interests focus on revenue generation in commercialized spectator sport settings.

McEvoy has published articles in the Journal of Sport Management, Sport Management Review, Sport Marketing Quarterly, and International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing. His research has been featured in stories from more than 100 media outlets, such as the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, PBS Newshour With Jim Lehrer, New York Daily News, and USA Today. He also appeared as a panelist before the prestigious Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics in 2008.

McEvoy is currently the president of the Sport Marketing Association and previously served as editor of Case Studies in Sport Management and co-editor of the Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics. His professional affiliations include the North American Society for Sport Management and the Sport Marketing Association.

Begin the research process by choosing the right problem or topic to explore

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore.

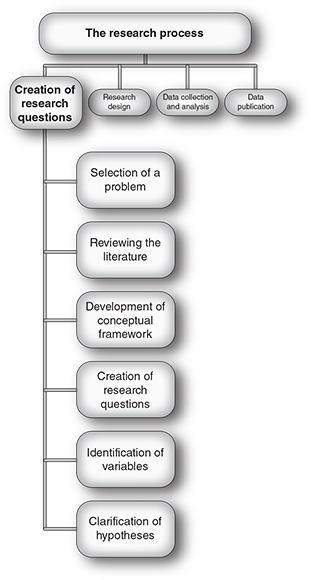

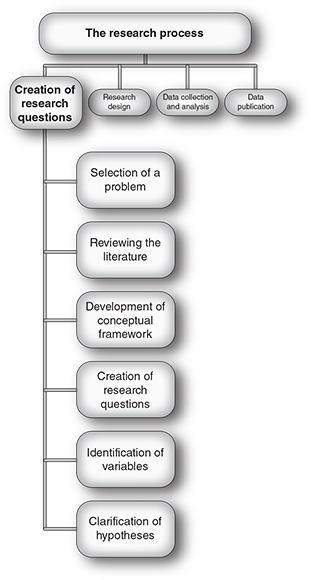

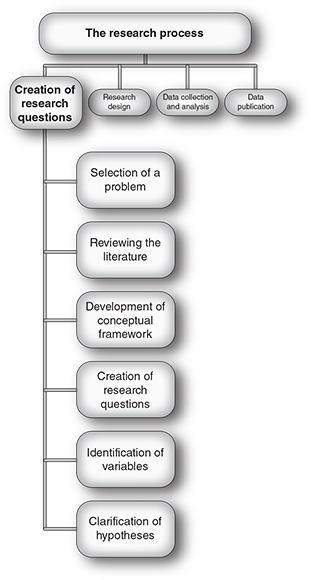

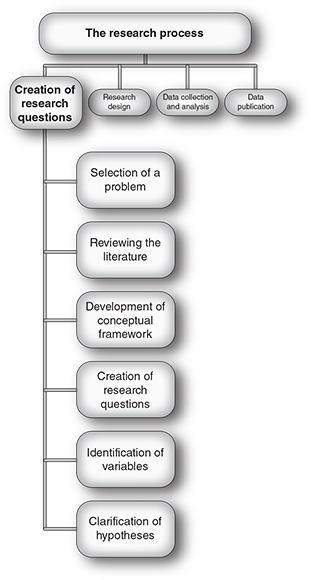

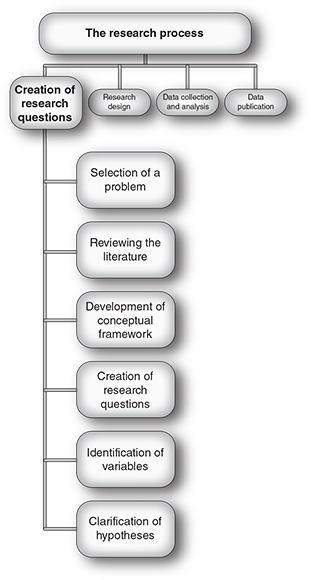

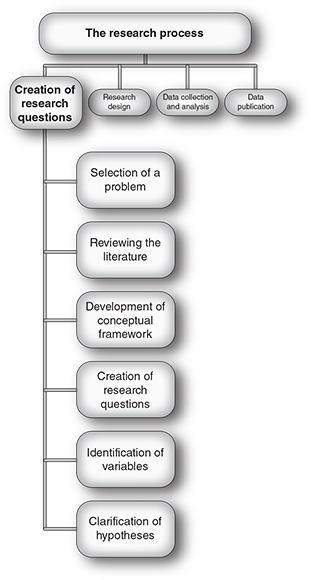

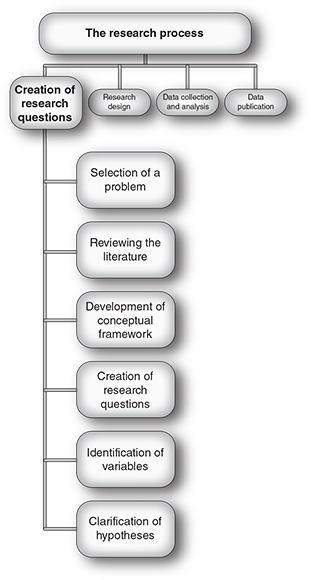

Figure 3.1 Steps for creating research questions.

Problem Selection

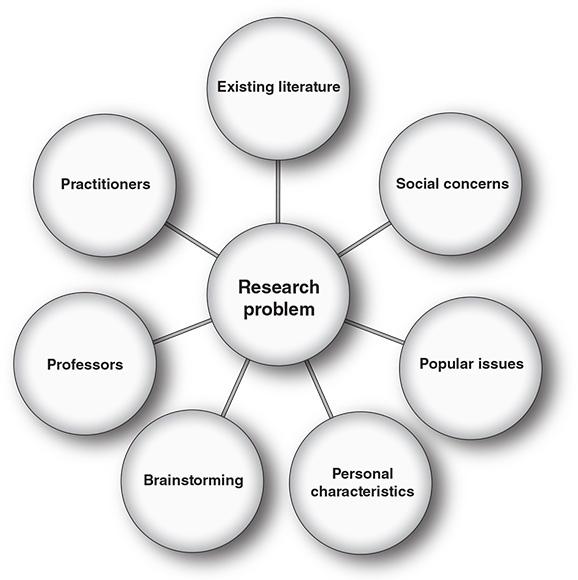

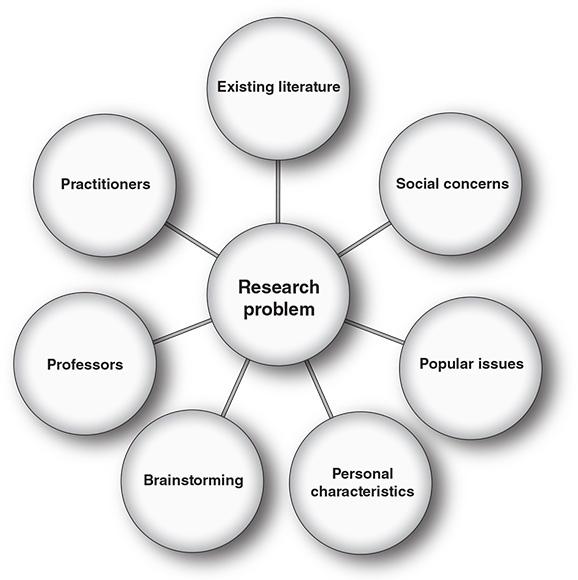

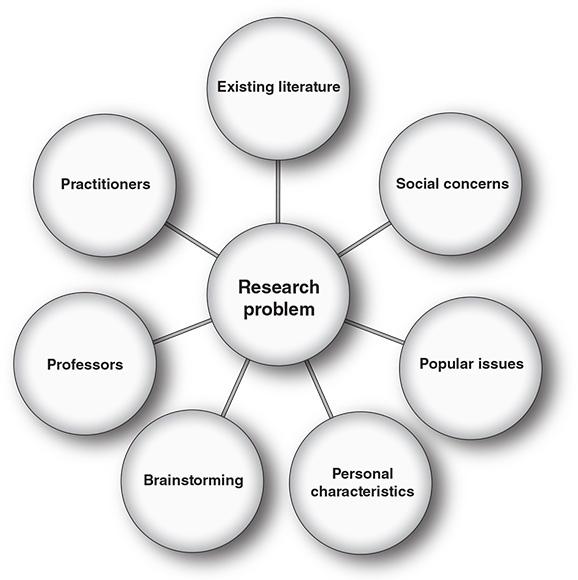

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore. This stage can be particularly daunting for novice researchers, who may feel that they do not possess enough knowledge about particular sport management topics that need further exploration. It may be encouraging for new researchers to know that this concern can affect all sport management researchers, regardless of how much experience they have with a given topic or problem area, because the more educated one becomes, the more one realizes how much one does not know about various problems both within and beyond the realm of sport. To help you address this challenge, we provided (in chapter 1) a list of research topic areas as a starting point for considering sport management subdisciplines and their context areas. Once you choose a general topic of interest, you can identify potential research problems by examining the existing literature, considering social concerns and popular issues, exploring your personal background, brainstorming ideas, and talking with professors and practitioners. Figure 3.2 illustrates a personalized approach to selecting a research problem.

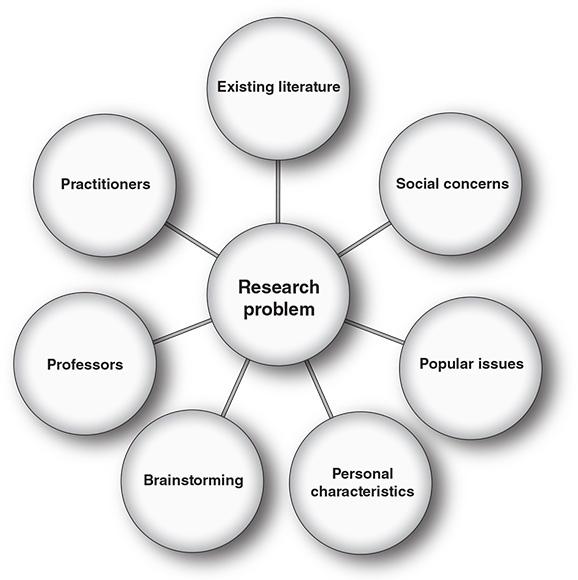

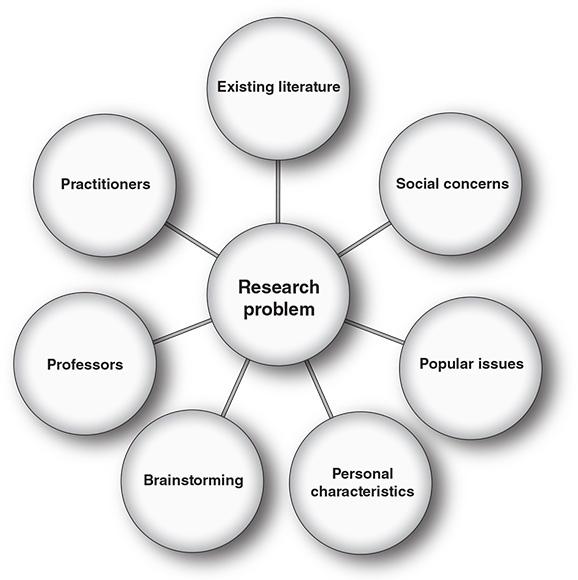

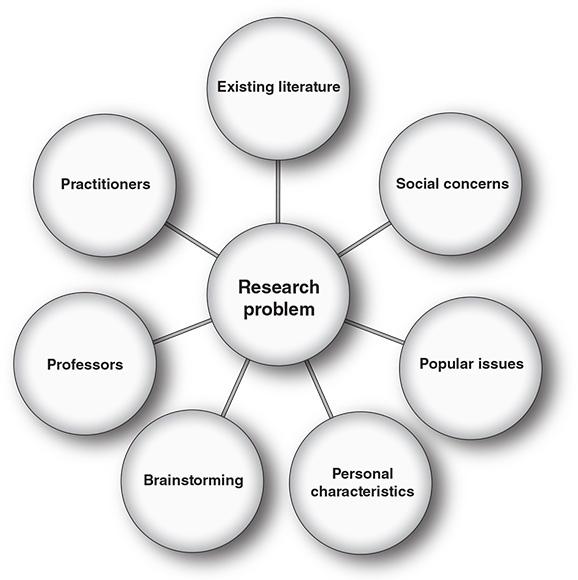

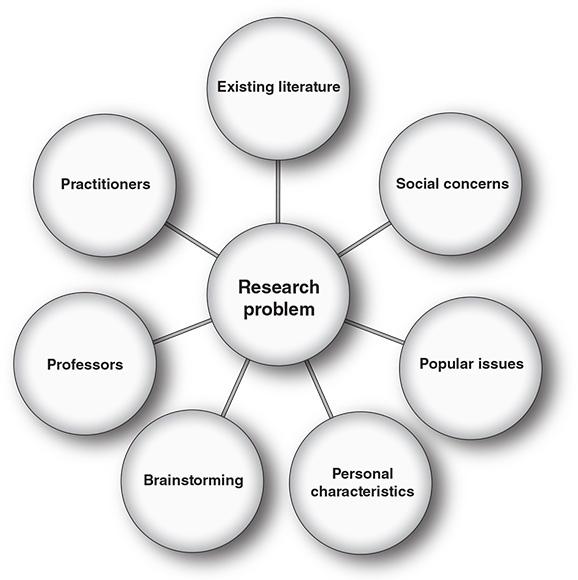

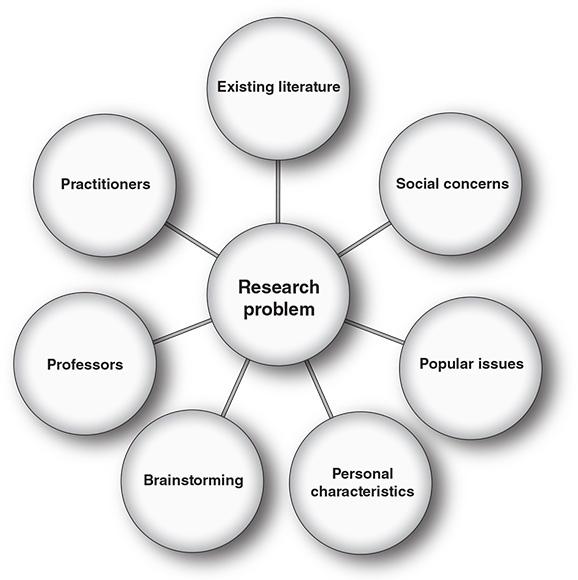

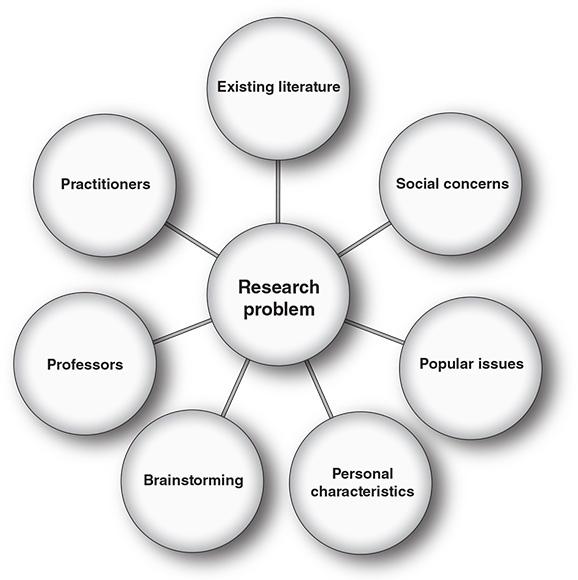

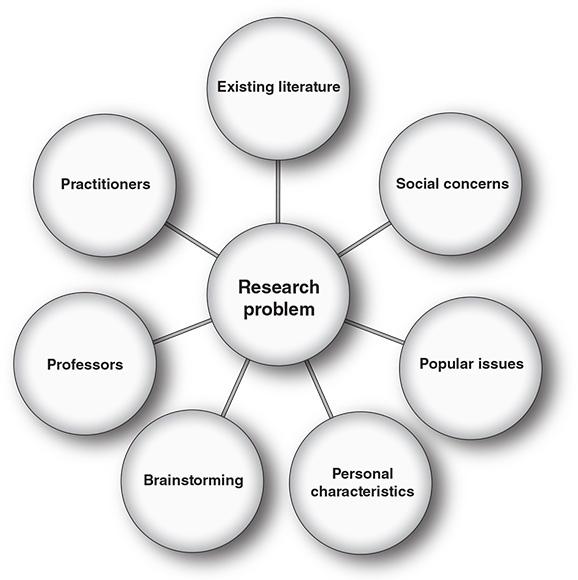

Figure 3.2 A personalized approach to selecting a research problem. Here are some questions to ask: What issues are emerging in the literature? What research problems could be answered to benefit society; for example, what are the effects of large-scale sporting events on local economies? What contemporary topics are being discussed in the media (e.g., the Olympics)? What experiences from your background might lead to a research study; for example, are you a recreational skier or a sport marketing student? Who can you collaborate with to develop a research problem? What issues are faculty researching, teaching, and discussing? What issues are sport industry professionals facing in the field?

Existing literature. This is perhaps the most obvious source of potential research problems or topics, and you can scan the literature in various ways. For example, if you are comfortable with the general area into which your specific topic falls, you might search electronic databases with specific search terms already in mind. As your search for more specific information progresses, you might narrow or broaden the original search terms depending on the number and quality of sources you find. Alternatively, if you are struggling to select a problem, you might begin your search by perusing printed sources, such as recent editions of peer-reviewed journals; specifically, you might scan the table of contents in various journals until you have identified a number of potential areas of interest. You can then explore these problem areas and narrow your focus. Using existing literature to generate research ideas also enables you to become familiar with previous attempts to address your selected problem, as well as the various approaches that have been used. Remember, too, that many well-written journal articles conclude by identifying avenues for further research about the problem. This is a service to the field and offers ideas for work that you might choose to do.

Social concerns. Research ideas rooted in contemporary social concerns include problems such as the integration of individuals with disabilities into sport and society (Andrew & Grady, 2005; Grady & Andrew, 2003, 2006, 2007; Hums, Moorman, & Wolff, 2003), the impact of diversity in the workplace (Cunningham, 2007; Cunningham & Sagas, 2007; Fink & Cunningham, 2005), and using sport for peace and development (Welty Peachey, Burton, Wells, & Ryoung Chung, 2018; Wright, Jacobs, Howell, & Ressler, 2018). Researchers who select their topics based on social concerns may also enjoy an additional benefit insofar as their research may be a vehicle for social reform.

Popular issues. Research ideas may also be found in the wide range of popular contemporary issues discussed on websites and in newspapers and magazines. If you take this approach, it is crucial to choose a high-quality website or print publication that will have a thorough review of problems that may be of interest. One disadvantage of basing a research problem on popular issues is that they are often so contemporary and novel that they may not have generated a research base yet within the academic literature. In addition, some emerging trends may quickly fade away. Competitive video gaming, or e-sports, has exploded in popularity during the decade of the 2010s, but it is unclear whether it will continue this dramatic growth in the next decade or lose popularity. Yet, popular issues can serve as valuable sources for identifying new areas for discovery, and certain subdisciplines of sport management (e.g., sport law) are more reliant on popular issues than others.

Your own personal characteristics. Sport management researchers hail from a variety of cultures and backgrounds, and their experiences can serve as a platform for research problems. For instance, Todd and Andrew (2008) explored the impact of having satisfying tasks to do and organizational support on the job attitudes of sporting goods retail employees. As the researchers explained, “Given the importance of satisfaction and commitment outcomes to sales force turnover, the possibility that environmental factors in sporting goods retail could alter employee attitudes, and the absence of research in the area, we proposed to extend the literature by highlighting the impact of intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organisational support on the job satisfaction and commitment of sporting goods retail employees” (p. 380). Ultimately, the researchers discovered that intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organizational support contributed significantly to the prediction of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. In other words, sporting goods retail employees who were given more intrinsically satisfying tasks (e.g., tennis-playing employees who are assigned to work in the store's tennis department) and who perceived organizational support (e.g., employees who believe that the organization has their best interest in mind, supports them, and writes policies that will benefit them) are more satisfied with their jobs and are more likely to want to continue working for that organization. The idea for this particular study was generated through Todd and Andrew's cumulative work experiences, some of which involved managerial responsibility in the sporting goods retail setting. As they discuss in their article, these work experiences impressed on them the importance of controlling staff turnover, as well as the uniqueness of the context of sport, in the retail setting.

Brainstorming. Generally speaking, brainstorming is a group activity with the expressed purpose of generating a large number of potential solutions to a problem. It can also be a good way to generate research ideas. As ideas and terms emerge during brainstorming, key phrases are written down and then related to each other in generative ways. Discussing ideas with others often helps a researcher develop and refine possible research questions, which is a great advantage of collaborative research. One of the key benefits of attending academic conferences is connecting with colleagues from other institutions, spending time discussing potential ideas for collaborative research.

Faculty. One of the many duties typically assigned to professors is the publication or presentation of scholarly research. As a result, they typically focus on a modest number of research topics and design research projects to facilitate their further exploration. Therefore, although faculty receive their academic credentials from an overall field of study, they usually develop expertise in a few focused areas within that field. With this in mind, one way to generate research ideas is to open a dialogue with professors who hold research interests similar to your own. For students, establishing mentoring relationships with faculty members can be integral in getting their own research started, and participating in a professor's research project commonly serves as a first foray into becoming a researcher. Others may find a research problem idea in a conversation with a professor or in something a professor discusses in a classroom lecture.

Practitioners. Another potentially valuable source for research ideas is sport management practitioners, who can often identify applied problems within the field that they have encountered through their work experiences. In a critique of the existing sport management research at the time, Weese (1995) lamented that sport management scholars were not serving the needs of practitioners, and unfortunately, much of his critique remains valid more than two decades later. By involving practitioners in topic selection, you can help ensure that your study will be pertinent to those working in the field. In one example, McEvoy and Morse (2007) examined how attendance at an NCAA Division I men's basketball program's games was affected by whether the game was televised. The study originated in a conversation McEvoy had with the athletic director of an NCAA Division I school, who said that he believed televising games would cause potential spectators to stay home and watch games on television rather than purchase tickets and attend the games in person. McEvoy, in contrast, hypothesized that televising the school's games would expose potential spectators to the product, serve as a 2-hour advertisement of sorts for the school and its athletic teams, and potentially add a layer of excitement to the game itself because of the presence of television. McEvoy and Morse designed a study to test the relationship between game attendance and the televising of games while controlling for other variables that might affect this relationship, such as the strength of the opponent and the day of the week. They found that attendance increased by 6.3 percent when games were televised, thus illustrating how involving practitioners in the process of generating research problems can lead to research that is practical and actionable in the industry. In this example, practitioners considering whether to televise their games were able to rely not only on their hunches and instincts but also on data-based research in making such a decision.

After assimilating a number of sources regarding a potential research topic, researchers sometimes find that a past study has already addressed their original research idea. Such a discovery, however, does not necessarily indicate that further research is moot in the chosen area. Veal (1997) suggested some ways in which researchers can build on earlier research in the field. First, the results of any study may vary according to the geographic background of the sample; for example, an analysis of cricket fans' attitudes in Australia is not particularly generalizable to cricket fans in Canada. Indeed, several sport management studies have focused on cross-national differences found in samples from two different countries on topics ranging from leadership behavior (Chelladurai, Imamura, Yamaguchi, Oinuma, & Miyauchi, 1988) to the consumption motivations of MMA fans (Kim, Andrew, & Greenwell, 2009). Therefore, a researcher can consider conducting a new study using fans from a different targeted geographic area. Second, past studies in a particular problem area may have devoted less attention to some social groups than to others. The impetus for analyzing neglected social groups may be to highlight an underrepresented social group or to respond to changing societal demographics. For example, a growing Latino population in the United States has recently generated a stream of sport marketing research about patterns of sport consumption by Latinos (Harrolle & Trail, 2007; Mercado, 2008). Furthermore, determining the applicability of past research (or the lack thereof) to particular social groups can often lead to the advancement of theory in the field.

Another way to complement past research is to offer a temporal update of an earlier research project. This approach allows a researcher not only to provide an up-to-date snapshot of current trends in the area but also to initiate data comparisons between past and present research. Significant events in history can also provide a supportive rationale for a modern treatment of earlier research. For example, a researcher interested in the perceived security of spectators at sporting events might not feel comfortable relying on results reported before the tragic events of September 11, 2001, in the United States, because that event has ramped up the need for security at major events held throughout the world.

Fourth, researchers may identify existing theories outside the realm of sport and propose to test them in the unique context of sport. Such a contextual approach can also be used to revisit existing research under modern theoretical paradigms to determine whether the new theoretical approaches provide greater explanatory power.

A final approach whereby researchers can build on earlier research is to adapt a novel method of analysis to explore a phenomenon. For example, a researcher might follow up a previously published qualitative study with a quantitative approach that focuses on testing theory with a larger sample. Researchers can also help confirm findings generated by earlier research by using alternative designs (e.g., using a survey to follow up on findings from in-depth interview data).

Analytical techniques and metrics in sport

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport.

By David P. Hedlund and Steven M. Howell

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport. In Major League Baseball (MLB), for example, advanced statistics such as Wins Above Replacement (WAR) have proven to be better metrics for evaluating player performance than more traditional statistics such as home runs (HR), batting average (BA), or runs batted in (RBI). Generally speaking, rigorous quantitative analysis and big data analytics in sports have been successfully implemented on both the business (e.g., social media, ticket pricing, stadium financing, etc.) and the performance (e.g., player evaluation/performance, in-game strategies, positioning, etc.) sides of the sports industry. In short, “people in both fields operate with beliefs and biases. To the extent you can eliminate both and replace them with data, you gain a clear advantage” (Lewis, 2003, pp. 90-91).

Analyzing social network data

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

By Adam Love and Amy Chan Hyung Kim

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

Connection and Distance

When analyzing an actor's attributes and behavior, it is likely that the more connections one has within a network, the more one is exposed to more diverse information (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Scott, 2017). In addition, items ranging from information to disease spread more quickly if there are more connections among actors in a network. Further, people who are more highly connected may be able to better obtain and use their resources and access more diverse perspectives to resolve issues. Thus, SNA can be useful in examining the consequences of variations in the degree of connection among actors (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). In doing so, two important concepts are relevant: connection and distance.

To examine the extent of connection in a network, a researcher must know the number of actors, the number of possible connections, and the number of connections that are actually present between actors in a network. Two important factors include differences in the size of networks and the extent to which actors are connected, which is known as density. The density of a network is simply the proportion of all possible ties that are actually present. For a valued network, density is calculated as the sum of the ties divided by the number of possible ties. The density of a given network provides insight about the ways in which information may diffuse between actors and how a certain actor may possess a high level of social capital and/or social isolation (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

The concept of distance refers to the characteristics of the network that are relevant to adjacencies: the direct tie from one actor to another. The larger the distance between actors, the longer it takes to diffuse information within a network. Distance is measured in terms of the number of “steps” from one actor to another; in other words, if two actors are adjacent to one another, the distance between them is 1, meaning it takes one step to go from the source to the receiver (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

Centrality and Power

The concept of centrality provides insight about power dynamics. From a social network perspective, one cannot have power without connections, and power may result from a person's ability to influence other actors in a network (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To study the ways in which a person's position in a network may influence power, we present three types of centrality: degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality (Borgatti et al., 2013).

Degree centrality focuses on how many connections a given actor has in a network. If a network contains directed relationships between actors, it is also important to distinguish between in-degree centrality and out-degree centrality. If one actor has four incoming connections, the in-degree centrality is four. If one actor has five outgoing connections, the out-degree centrality of that actor is five (Freeman, 1979). Degree centrality tends to measure only the immediate ties that an actor has, overlooking the importance of indirect ties to others in the network. In other words, one actor may be directly tied to a large number of other actors, but those actors may be disconnected from the whole network. In this case, this actor may be positioned as a central actor, but only in a local neighborhood (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To understand the indirect ties of an actor, closeness centrality highlights the distance of an actor to all others in the network. Additionally, the person who lies between two actors can have power because information can pass between those two actors only through this broker. Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which an actor serves as an intermediary between other actors in a network.

Social Positions and Structural Equivalence

To investigate network positions and social roles, social network scholars have developed the idea of structural equivalence (Scott, 2017). In its simplest form, if two actors have a similar pattern of relationships with other actors, these two actors can be said to have the same or a similar position in the network. Scott explains this type of structural equivalence using the concept of “substitutable” or “interchangeable” actors. That is, if one's position can be occupied by an actor who has similar relational ties, these two actors' positions are said to be structurally equivalent. In other words, identifying uniformities within social positions is key to understanding structural equivalence. Once positions within a certain network are identified, the relations among these positions can be explored. Hanneman and Riddle (2005) describe two types of equivalence in addition to structural equivalence: automorphic equivalence and regular equivalence. If two actors have the exact same relationships to all other actors within a network, these two actors are considered to be structurally equivalent. Automorphic equivalence entails a less strict definition of equivalence. That is, sets of actors can be automorphically equivalent by being positioned in local structures that have the same patterns of ties. For example, assume that both the manager of a sales department and the manager of the human resource department have three employees each. Even though these two managers do not share the same three employees, each has a similar pattern of ties with three employees. Finally, two actors are considered to be regularly equivalent if they have the same pattern of ties with members of other sets of actors who are also regularly equivalent. In other words, actors who are regularly equivalent do not have to fall in the same network positions, but they do have the same types of relationships with members of another set of actors (Hanneman & Riddle).

Social Network Analysis Software

Several software packages for conducting SNA have been developed in recent years. The following list includes software packages that are developed specially for SNA and have their own graphical user interfaces (GUIs): Cytoscape, EgoWeb 2.0, Gephi, KrackPlot, NetMiner, NodeXL, Pajek, SocNetV, StOCNET, and UCINET. Readers should be aware that there are also social network analysis packages designed for programming languages such as R (i.e., a statistical computing software) or Python.

Here is a list of SNA software packages:

Cuttlefish

Cytoscape

EgoWeb 2.0

Gephi

KrackPlot

NetMiner

NodeXL

Pajek

SocNetV

StOCNET

UCINET

Begin the research process by choosing the right problem or topic to explore

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore.

Figure 3.1 Steps for creating research questions.

Problem Selection

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore. This stage can be particularly daunting for novice researchers, who may feel that they do not possess enough knowledge about particular sport management topics that need further exploration. It may be encouraging for new researchers to know that this concern can affect all sport management researchers, regardless of how much experience they have with a given topic or problem area, because the more educated one becomes, the more one realizes how much one does not know about various problems both within and beyond the realm of sport. To help you address this challenge, we provided (in chapter 1) a list of research topic areas as a starting point for considering sport management subdisciplines and their context areas. Once you choose a general topic of interest, you can identify potential research problems by examining the existing literature, considering social concerns and popular issues, exploring your personal background, brainstorming ideas, and talking with professors and practitioners. Figure 3.2 illustrates a personalized approach to selecting a research problem.

Figure 3.2 A personalized approach to selecting a research problem. Here are some questions to ask: What issues are emerging in the literature? What research problems could be answered to benefit society; for example, what are the effects of large-scale sporting events on local economies? What contemporary topics are being discussed in the media (e.g., the Olympics)? What experiences from your background might lead to a research study; for example, are you a recreational skier or a sport marketing student? Who can you collaborate with to develop a research problem? What issues are faculty researching, teaching, and discussing? What issues are sport industry professionals facing in the field?

Existing literature. This is perhaps the most obvious source of potential research problems or topics, and you can scan the literature in various ways. For example, if you are comfortable with the general area into which your specific topic falls, you might search electronic databases with specific search terms already in mind. As your search for more specific information progresses, you might narrow or broaden the original search terms depending on the number and quality of sources you find. Alternatively, if you are struggling to select a problem, you might begin your search by perusing printed sources, such as recent editions of peer-reviewed journals; specifically, you might scan the table of contents in various journals until you have identified a number of potential areas of interest. You can then explore these problem areas and narrow your focus. Using existing literature to generate research ideas also enables you to become familiar with previous attempts to address your selected problem, as well as the various approaches that have been used. Remember, too, that many well-written journal articles conclude by identifying avenues for further research about the problem. This is a service to the field and offers ideas for work that you might choose to do.

Social concerns. Research ideas rooted in contemporary social concerns include problems such as the integration of individuals with disabilities into sport and society (Andrew & Grady, 2005; Grady & Andrew, 2003, 2006, 2007; Hums, Moorman, & Wolff, 2003), the impact of diversity in the workplace (Cunningham, 2007; Cunningham & Sagas, 2007; Fink & Cunningham, 2005), and using sport for peace and development (Welty Peachey, Burton, Wells, & Ryoung Chung, 2018; Wright, Jacobs, Howell, & Ressler, 2018). Researchers who select their topics based on social concerns may also enjoy an additional benefit insofar as their research may be a vehicle for social reform.

Popular issues. Research ideas may also be found in the wide range of popular contemporary issues discussed on websites and in newspapers and magazines. If you take this approach, it is crucial to choose a high-quality website or print publication that will have a thorough review of problems that may be of interest. One disadvantage of basing a research problem on popular issues is that they are often so contemporary and novel that they may not have generated a research base yet within the academic literature. In addition, some emerging trends may quickly fade away. Competitive video gaming, or e-sports, has exploded in popularity during the decade of the 2010s, but it is unclear whether it will continue this dramatic growth in the next decade or lose popularity. Yet, popular issues can serve as valuable sources for identifying new areas for discovery, and certain subdisciplines of sport management (e.g., sport law) are more reliant on popular issues than others.

Your own personal characteristics. Sport management researchers hail from a variety of cultures and backgrounds, and their experiences can serve as a platform for research problems. For instance, Todd and Andrew (2008) explored the impact of having satisfying tasks to do and organizational support on the job attitudes of sporting goods retail employees. As the researchers explained, “Given the importance of satisfaction and commitment outcomes to sales force turnover, the possibility that environmental factors in sporting goods retail could alter employee attitudes, and the absence of research in the area, we proposed to extend the literature by highlighting the impact of intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organisational support on the job satisfaction and commitment of sporting goods retail employees” (p. 380). Ultimately, the researchers discovered that intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organizational support contributed significantly to the prediction of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. In other words, sporting goods retail employees who were given more intrinsically satisfying tasks (e.g., tennis-playing employees who are assigned to work in the store's tennis department) and who perceived organizational support (e.g., employees who believe that the organization has their best interest in mind, supports them, and writes policies that will benefit them) are more satisfied with their jobs and are more likely to want to continue working for that organization. The idea for this particular study was generated through Todd and Andrew's cumulative work experiences, some of which involved managerial responsibility in the sporting goods retail setting. As they discuss in their article, these work experiences impressed on them the importance of controlling staff turnover, as well as the uniqueness of the context of sport, in the retail setting.

Brainstorming. Generally speaking, brainstorming is a group activity with the expressed purpose of generating a large number of potential solutions to a problem. It can also be a good way to generate research ideas. As ideas and terms emerge during brainstorming, key phrases are written down and then related to each other in generative ways. Discussing ideas with others often helps a researcher develop and refine possible research questions, which is a great advantage of collaborative research. One of the key benefits of attending academic conferences is connecting with colleagues from other institutions, spending time discussing potential ideas for collaborative research.

Faculty. One of the many duties typically assigned to professors is the publication or presentation of scholarly research. As a result, they typically focus on a modest number of research topics and design research projects to facilitate their further exploration. Therefore, although faculty receive their academic credentials from an overall field of study, they usually develop expertise in a few focused areas within that field. With this in mind, one way to generate research ideas is to open a dialogue with professors who hold research interests similar to your own. For students, establishing mentoring relationships with faculty members can be integral in getting their own research started, and participating in a professor's research project commonly serves as a first foray into becoming a researcher. Others may find a research problem idea in a conversation with a professor or in something a professor discusses in a classroom lecture.

Practitioners. Another potentially valuable source for research ideas is sport management practitioners, who can often identify applied problems within the field that they have encountered through their work experiences. In a critique of the existing sport management research at the time, Weese (1995) lamented that sport management scholars were not serving the needs of practitioners, and unfortunately, much of his critique remains valid more than two decades later. By involving practitioners in topic selection, you can help ensure that your study will be pertinent to those working in the field. In one example, McEvoy and Morse (2007) examined how attendance at an NCAA Division I men's basketball program's games was affected by whether the game was televised. The study originated in a conversation McEvoy had with the athletic director of an NCAA Division I school, who said that he believed televising games would cause potential spectators to stay home and watch games on television rather than purchase tickets and attend the games in person. McEvoy, in contrast, hypothesized that televising the school's games would expose potential spectators to the product, serve as a 2-hour advertisement of sorts for the school and its athletic teams, and potentially add a layer of excitement to the game itself because of the presence of television. McEvoy and Morse designed a study to test the relationship between game attendance and the televising of games while controlling for other variables that might affect this relationship, such as the strength of the opponent and the day of the week. They found that attendance increased by 6.3 percent when games were televised, thus illustrating how involving practitioners in the process of generating research problems can lead to research that is practical and actionable in the industry. In this example, practitioners considering whether to televise their games were able to rely not only on their hunches and instincts but also on data-based research in making such a decision.

After assimilating a number of sources regarding a potential research topic, researchers sometimes find that a past study has already addressed their original research idea. Such a discovery, however, does not necessarily indicate that further research is moot in the chosen area. Veal (1997) suggested some ways in which researchers can build on earlier research in the field. First, the results of any study may vary according to the geographic background of the sample; for example, an analysis of cricket fans' attitudes in Australia is not particularly generalizable to cricket fans in Canada. Indeed, several sport management studies have focused on cross-national differences found in samples from two different countries on topics ranging from leadership behavior (Chelladurai, Imamura, Yamaguchi, Oinuma, & Miyauchi, 1988) to the consumption motivations of MMA fans (Kim, Andrew, & Greenwell, 2009). Therefore, a researcher can consider conducting a new study using fans from a different targeted geographic area. Second, past studies in a particular problem area may have devoted less attention to some social groups than to others. The impetus for analyzing neglected social groups may be to highlight an underrepresented social group or to respond to changing societal demographics. For example, a growing Latino population in the United States has recently generated a stream of sport marketing research about patterns of sport consumption by Latinos (Harrolle & Trail, 2007; Mercado, 2008). Furthermore, determining the applicability of past research (or the lack thereof) to particular social groups can often lead to the advancement of theory in the field.

Another way to complement past research is to offer a temporal update of an earlier research project. This approach allows a researcher not only to provide an up-to-date snapshot of current trends in the area but also to initiate data comparisons between past and present research. Significant events in history can also provide a supportive rationale for a modern treatment of earlier research. For example, a researcher interested in the perceived security of spectators at sporting events might not feel comfortable relying on results reported before the tragic events of September 11, 2001, in the United States, because that event has ramped up the need for security at major events held throughout the world.

Fourth, researchers may identify existing theories outside the realm of sport and propose to test them in the unique context of sport. Such a contextual approach can also be used to revisit existing research under modern theoretical paradigms to determine whether the new theoretical approaches provide greater explanatory power.

A final approach whereby researchers can build on earlier research is to adapt a novel method of analysis to explore a phenomenon. For example, a researcher might follow up a previously published qualitative study with a quantitative approach that focuses on testing theory with a larger sample. Researchers can also help confirm findings generated by earlier research by using alternative designs (e.g., using a survey to follow up on findings from in-depth interview data).

Analytical techniques and metrics in sport

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport.

By David P. Hedlund and Steven M. Howell

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport. In Major League Baseball (MLB), for example, advanced statistics such as Wins Above Replacement (WAR) have proven to be better metrics for evaluating player performance than more traditional statistics such as home runs (HR), batting average (BA), or runs batted in (RBI). Generally speaking, rigorous quantitative analysis and big data analytics in sports have been successfully implemented on both the business (e.g., social media, ticket pricing, stadium financing, etc.) and the performance (e.g., player evaluation/performance, in-game strategies, positioning, etc.) sides of the sports industry. In short, “people in both fields operate with beliefs and biases. To the extent you can eliminate both and replace them with data, you gain a clear advantage” (Lewis, 2003, pp. 90-91).

Analyzing social network data

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

By Adam Love and Amy Chan Hyung Kim

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

Connection and Distance

When analyzing an actor's attributes and behavior, it is likely that the more connections one has within a network, the more one is exposed to more diverse information (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Scott, 2017). In addition, items ranging from information to disease spread more quickly if there are more connections among actors in a network. Further, people who are more highly connected may be able to better obtain and use their resources and access more diverse perspectives to resolve issues. Thus, SNA can be useful in examining the consequences of variations in the degree of connection among actors (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). In doing so, two important concepts are relevant: connection and distance.

To examine the extent of connection in a network, a researcher must know the number of actors, the number of possible connections, and the number of connections that are actually present between actors in a network. Two important factors include differences in the size of networks and the extent to which actors are connected, which is known as density. The density of a network is simply the proportion of all possible ties that are actually present. For a valued network, density is calculated as the sum of the ties divided by the number of possible ties. The density of a given network provides insight about the ways in which information may diffuse between actors and how a certain actor may possess a high level of social capital and/or social isolation (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

The concept of distance refers to the characteristics of the network that are relevant to adjacencies: the direct tie from one actor to another. The larger the distance between actors, the longer it takes to diffuse information within a network. Distance is measured in terms of the number of “steps” from one actor to another; in other words, if two actors are adjacent to one another, the distance between them is 1, meaning it takes one step to go from the source to the receiver (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

Centrality and Power

The concept of centrality provides insight about power dynamics. From a social network perspective, one cannot have power without connections, and power may result from a person's ability to influence other actors in a network (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To study the ways in which a person's position in a network may influence power, we present three types of centrality: degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality (Borgatti et al., 2013).

Degree centrality focuses on how many connections a given actor has in a network. If a network contains directed relationships between actors, it is also important to distinguish between in-degree centrality and out-degree centrality. If one actor has four incoming connections, the in-degree centrality is four. If one actor has five outgoing connections, the out-degree centrality of that actor is five (Freeman, 1979). Degree centrality tends to measure only the immediate ties that an actor has, overlooking the importance of indirect ties to others in the network. In other words, one actor may be directly tied to a large number of other actors, but those actors may be disconnected from the whole network. In this case, this actor may be positioned as a central actor, but only in a local neighborhood (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To understand the indirect ties of an actor, closeness centrality highlights the distance of an actor to all others in the network. Additionally, the person who lies between two actors can have power because information can pass between those two actors only through this broker. Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which an actor serves as an intermediary between other actors in a network.

Social Positions and Structural Equivalence

To investigate network positions and social roles, social network scholars have developed the idea of structural equivalence (Scott, 2017). In its simplest form, if two actors have a similar pattern of relationships with other actors, these two actors can be said to have the same or a similar position in the network. Scott explains this type of structural equivalence using the concept of “substitutable” or “interchangeable” actors. That is, if one's position can be occupied by an actor who has similar relational ties, these two actors' positions are said to be structurally equivalent. In other words, identifying uniformities within social positions is key to understanding structural equivalence. Once positions within a certain network are identified, the relations among these positions can be explored. Hanneman and Riddle (2005) describe two types of equivalence in addition to structural equivalence: automorphic equivalence and regular equivalence. If two actors have the exact same relationships to all other actors within a network, these two actors are considered to be structurally equivalent. Automorphic equivalence entails a less strict definition of equivalence. That is, sets of actors can be automorphically equivalent by being positioned in local structures that have the same patterns of ties. For example, assume that both the manager of a sales department and the manager of the human resource department have three employees each. Even though these two managers do not share the same three employees, each has a similar pattern of ties with three employees. Finally, two actors are considered to be regularly equivalent if they have the same pattern of ties with members of other sets of actors who are also regularly equivalent. In other words, actors who are regularly equivalent do not have to fall in the same network positions, but they do have the same types of relationships with members of another set of actors (Hanneman & Riddle).

Social Network Analysis Software

Several software packages for conducting SNA have been developed in recent years. The following list includes software packages that are developed specially for SNA and have their own graphical user interfaces (GUIs): Cytoscape, EgoWeb 2.0, Gephi, KrackPlot, NetMiner, NodeXL, Pajek, SocNetV, StOCNET, and UCINET. Readers should be aware that there are also social network analysis packages designed for programming languages such as R (i.e., a statistical computing software) or Python.

Here is a list of SNA software packages:

Cuttlefish

Cytoscape

EgoWeb 2.0

Gephi

KrackPlot

NetMiner

NodeXL

Pajek

SocNetV

StOCNET

UCINET

Begin the research process by choosing the right problem or topic to explore

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore.

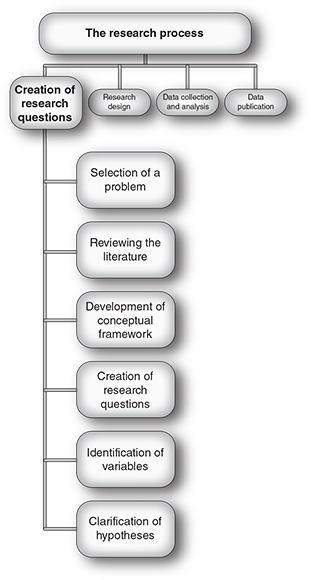

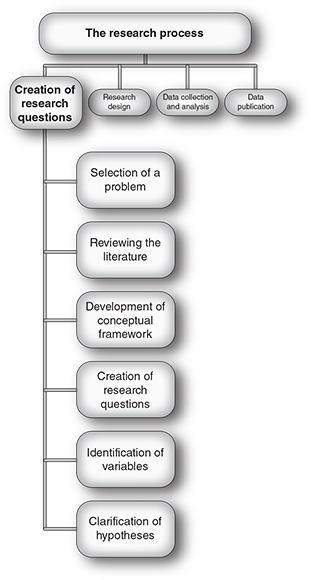

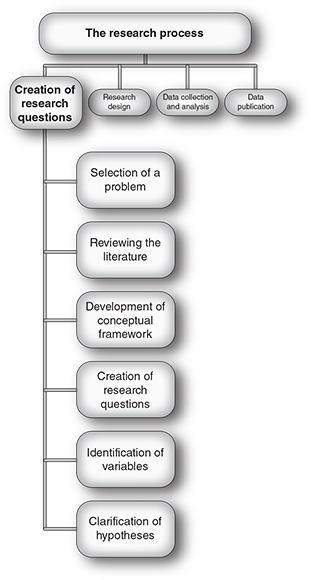

Figure 3.1 Steps for creating research questions.

Problem Selection

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore. This stage can be particularly daunting for novice researchers, who may feel that they do not possess enough knowledge about particular sport management topics that need further exploration. It may be encouraging for new researchers to know that this concern can affect all sport management researchers, regardless of how much experience they have with a given topic or problem area, because the more educated one becomes, the more one realizes how much one does not know about various problems both within and beyond the realm of sport. To help you address this challenge, we provided (in chapter 1) a list of research topic areas as a starting point for considering sport management subdisciplines and their context areas. Once you choose a general topic of interest, you can identify potential research problems by examining the existing literature, considering social concerns and popular issues, exploring your personal background, brainstorming ideas, and talking with professors and practitioners. Figure 3.2 illustrates a personalized approach to selecting a research problem.

Figure 3.2 A personalized approach to selecting a research problem. Here are some questions to ask: What issues are emerging in the literature? What research problems could be answered to benefit society; for example, what are the effects of large-scale sporting events on local economies? What contemporary topics are being discussed in the media (e.g., the Olympics)? What experiences from your background might lead to a research study; for example, are you a recreational skier or a sport marketing student? Who can you collaborate with to develop a research problem? What issues are faculty researching, teaching, and discussing? What issues are sport industry professionals facing in the field?

Existing literature. This is perhaps the most obvious source of potential research problems or topics, and you can scan the literature in various ways. For example, if you are comfortable with the general area into which your specific topic falls, you might search electronic databases with specific search terms already in mind. As your search for more specific information progresses, you might narrow or broaden the original search terms depending on the number and quality of sources you find. Alternatively, if you are struggling to select a problem, you might begin your search by perusing printed sources, such as recent editions of peer-reviewed journals; specifically, you might scan the table of contents in various journals until you have identified a number of potential areas of interest. You can then explore these problem areas and narrow your focus. Using existing literature to generate research ideas also enables you to become familiar with previous attempts to address your selected problem, as well as the various approaches that have been used. Remember, too, that many well-written journal articles conclude by identifying avenues for further research about the problem. This is a service to the field and offers ideas for work that you might choose to do.

Social concerns. Research ideas rooted in contemporary social concerns include problems such as the integration of individuals with disabilities into sport and society (Andrew & Grady, 2005; Grady & Andrew, 2003, 2006, 2007; Hums, Moorman, & Wolff, 2003), the impact of diversity in the workplace (Cunningham, 2007; Cunningham & Sagas, 2007; Fink & Cunningham, 2005), and using sport for peace and development (Welty Peachey, Burton, Wells, & Ryoung Chung, 2018; Wright, Jacobs, Howell, & Ressler, 2018). Researchers who select their topics based on social concerns may also enjoy an additional benefit insofar as their research may be a vehicle for social reform.

Popular issues. Research ideas may also be found in the wide range of popular contemporary issues discussed on websites and in newspapers and magazines. If you take this approach, it is crucial to choose a high-quality website or print publication that will have a thorough review of problems that may be of interest. One disadvantage of basing a research problem on popular issues is that they are often so contemporary and novel that they may not have generated a research base yet within the academic literature. In addition, some emerging trends may quickly fade away. Competitive video gaming, or e-sports, has exploded in popularity during the decade of the 2010s, but it is unclear whether it will continue this dramatic growth in the next decade or lose popularity. Yet, popular issues can serve as valuable sources for identifying new areas for discovery, and certain subdisciplines of sport management (e.g., sport law) are more reliant on popular issues than others.

Your own personal characteristics. Sport management researchers hail from a variety of cultures and backgrounds, and their experiences can serve as a platform for research problems. For instance, Todd and Andrew (2008) explored the impact of having satisfying tasks to do and organizational support on the job attitudes of sporting goods retail employees. As the researchers explained, “Given the importance of satisfaction and commitment outcomes to sales force turnover, the possibility that environmental factors in sporting goods retail could alter employee attitudes, and the absence of research in the area, we proposed to extend the literature by highlighting the impact of intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organisational support on the job satisfaction and commitment of sporting goods retail employees” (p. 380). Ultimately, the researchers discovered that intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organizational support contributed significantly to the prediction of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. In other words, sporting goods retail employees who were given more intrinsically satisfying tasks (e.g., tennis-playing employees who are assigned to work in the store's tennis department) and who perceived organizational support (e.g., employees who believe that the organization has their best interest in mind, supports them, and writes policies that will benefit them) are more satisfied with their jobs and are more likely to want to continue working for that organization. The idea for this particular study was generated through Todd and Andrew's cumulative work experiences, some of which involved managerial responsibility in the sporting goods retail setting. As they discuss in their article, these work experiences impressed on them the importance of controlling staff turnover, as well as the uniqueness of the context of sport, in the retail setting.

Brainstorming. Generally speaking, brainstorming is a group activity with the expressed purpose of generating a large number of potential solutions to a problem. It can also be a good way to generate research ideas. As ideas and terms emerge during brainstorming, key phrases are written down and then related to each other in generative ways. Discussing ideas with others often helps a researcher develop and refine possible research questions, which is a great advantage of collaborative research. One of the key benefits of attending academic conferences is connecting with colleagues from other institutions, spending time discussing potential ideas for collaborative research.

Faculty. One of the many duties typically assigned to professors is the publication or presentation of scholarly research. As a result, they typically focus on a modest number of research topics and design research projects to facilitate their further exploration. Therefore, although faculty receive their academic credentials from an overall field of study, they usually develop expertise in a few focused areas within that field. With this in mind, one way to generate research ideas is to open a dialogue with professors who hold research interests similar to your own. For students, establishing mentoring relationships with faculty members can be integral in getting their own research started, and participating in a professor's research project commonly serves as a first foray into becoming a researcher. Others may find a research problem idea in a conversation with a professor or in something a professor discusses in a classroom lecture.

Practitioners. Another potentially valuable source for research ideas is sport management practitioners, who can often identify applied problems within the field that they have encountered through their work experiences. In a critique of the existing sport management research at the time, Weese (1995) lamented that sport management scholars were not serving the needs of practitioners, and unfortunately, much of his critique remains valid more than two decades later. By involving practitioners in topic selection, you can help ensure that your study will be pertinent to those working in the field. In one example, McEvoy and Morse (2007) examined how attendance at an NCAA Division I men's basketball program's games was affected by whether the game was televised. The study originated in a conversation McEvoy had with the athletic director of an NCAA Division I school, who said that he believed televising games would cause potential spectators to stay home and watch games on television rather than purchase tickets and attend the games in person. McEvoy, in contrast, hypothesized that televising the school's games would expose potential spectators to the product, serve as a 2-hour advertisement of sorts for the school and its athletic teams, and potentially add a layer of excitement to the game itself because of the presence of television. McEvoy and Morse designed a study to test the relationship between game attendance and the televising of games while controlling for other variables that might affect this relationship, such as the strength of the opponent and the day of the week. They found that attendance increased by 6.3 percent when games were televised, thus illustrating how involving practitioners in the process of generating research problems can lead to research that is practical and actionable in the industry. In this example, practitioners considering whether to televise their games were able to rely not only on their hunches and instincts but also on data-based research in making such a decision.

After assimilating a number of sources regarding a potential research topic, researchers sometimes find that a past study has already addressed their original research idea. Such a discovery, however, does not necessarily indicate that further research is moot in the chosen area. Veal (1997) suggested some ways in which researchers can build on earlier research in the field. First, the results of any study may vary according to the geographic background of the sample; for example, an analysis of cricket fans' attitudes in Australia is not particularly generalizable to cricket fans in Canada. Indeed, several sport management studies have focused on cross-national differences found in samples from two different countries on topics ranging from leadership behavior (Chelladurai, Imamura, Yamaguchi, Oinuma, & Miyauchi, 1988) to the consumption motivations of MMA fans (Kim, Andrew, & Greenwell, 2009). Therefore, a researcher can consider conducting a new study using fans from a different targeted geographic area. Second, past studies in a particular problem area may have devoted less attention to some social groups than to others. The impetus for analyzing neglected social groups may be to highlight an underrepresented social group or to respond to changing societal demographics. For example, a growing Latino population in the United States has recently generated a stream of sport marketing research about patterns of sport consumption by Latinos (Harrolle & Trail, 2007; Mercado, 2008). Furthermore, determining the applicability of past research (or the lack thereof) to particular social groups can often lead to the advancement of theory in the field.

Another way to complement past research is to offer a temporal update of an earlier research project. This approach allows a researcher not only to provide an up-to-date snapshot of current trends in the area but also to initiate data comparisons between past and present research. Significant events in history can also provide a supportive rationale for a modern treatment of earlier research. For example, a researcher interested in the perceived security of spectators at sporting events might not feel comfortable relying on results reported before the tragic events of September 11, 2001, in the United States, because that event has ramped up the need for security at major events held throughout the world.

Fourth, researchers may identify existing theories outside the realm of sport and propose to test them in the unique context of sport. Such a contextual approach can also be used to revisit existing research under modern theoretical paradigms to determine whether the new theoretical approaches provide greater explanatory power.

A final approach whereby researchers can build on earlier research is to adapt a novel method of analysis to explore a phenomenon. For example, a researcher might follow up a previously published qualitative study with a quantitative approach that focuses on testing theory with a larger sample. Researchers can also help confirm findings generated by earlier research by using alternative designs (e.g., using a survey to follow up on findings from in-depth interview data).

Analytical techniques and metrics in sport

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport.

By David P. Hedlund and Steven M. Howell

Analytical techniques in sport are used to provide sport professionals the relevant information necessary to make as informed of a decision as possible in business or performance aspects of sport. In Major League Baseball (MLB), for example, advanced statistics such as Wins Above Replacement (WAR) have proven to be better metrics for evaluating player performance than more traditional statistics such as home runs (HR), batting average (BA), or runs batted in (RBI). Generally speaking, rigorous quantitative analysis and big data analytics in sports have been successfully implemented on both the business (e.g., social media, ticket pricing, stadium financing, etc.) and the performance (e.g., player evaluation/performance, in-game strategies, positioning, etc.) sides of the sports industry. In short, “people in both fields operate with beliefs and biases. To the extent you can eliminate both and replace them with data, you gain a clear advantage” (Lewis, 2003, pp. 90-91).

Analyzing social network data

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

By Adam Love and Amy Chan Hyung Kim

In this section, we introduce some key theoretical concepts used in social network data analysis and identify several software packages that may be used in conducting an SNA.

Connection and Distance

When analyzing an actor's attributes and behavior, it is likely that the more connections one has within a network, the more one is exposed to more diverse information (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005; Scott, 2017). In addition, items ranging from information to disease spread more quickly if there are more connections among actors in a network. Further, people who are more highly connected may be able to better obtain and use their resources and access more diverse perspectives to resolve issues. Thus, SNA can be useful in examining the consequences of variations in the degree of connection among actors (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). In doing so, two important concepts are relevant: connection and distance.

To examine the extent of connection in a network, a researcher must know the number of actors, the number of possible connections, and the number of connections that are actually present between actors in a network. Two important factors include differences in the size of networks and the extent to which actors are connected, which is known as density. The density of a network is simply the proportion of all possible ties that are actually present. For a valued network, density is calculated as the sum of the ties divided by the number of possible ties. The density of a given network provides insight about the ways in which information may diffuse between actors and how a certain actor may possess a high level of social capital and/or social isolation (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

The concept of distance refers to the characteristics of the network that are relevant to adjacencies: the direct tie from one actor to another. The larger the distance between actors, the longer it takes to diffuse information within a network. Distance is measured in terms of the number of “steps” from one actor to another; in other words, if two actors are adjacent to one another, the distance between them is 1, meaning it takes one step to go from the source to the receiver (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005).

Centrality and Power

The concept of centrality provides insight about power dynamics. From a social network perspective, one cannot have power without connections, and power may result from a person's ability to influence other actors in a network (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To study the ways in which a person's position in a network may influence power, we present three types of centrality: degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality (Borgatti et al., 2013).

Degree centrality focuses on how many connections a given actor has in a network. If a network contains directed relationships between actors, it is also important to distinguish between in-degree centrality and out-degree centrality. If one actor has four incoming connections, the in-degree centrality is four. If one actor has five outgoing connections, the out-degree centrality of that actor is five (Freeman, 1979). Degree centrality tends to measure only the immediate ties that an actor has, overlooking the importance of indirect ties to others in the network. In other words, one actor may be directly tied to a large number of other actors, but those actors may be disconnected from the whole network. In this case, this actor may be positioned as a central actor, but only in a local neighborhood (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). To understand the indirect ties of an actor, closeness centrality highlights the distance of an actor to all others in the network. Additionally, the person who lies between two actors can have power because information can pass between those two actors only through this broker. Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which an actor serves as an intermediary between other actors in a network.

Social Positions and Structural Equivalence

To investigate network positions and social roles, social network scholars have developed the idea of structural equivalence (Scott, 2017). In its simplest form, if two actors have a similar pattern of relationships with other actors, these two actors can be said to have the same or a similar position in the network. Scott explains this type of structural equivalence using the concept of “substitutable” or “interchangeable” actors. That is, if one's position can be occupied by an actor who has similar relational ties, these two actors' positions are said to be structurally equivalent. In other words, identifying uniformities within social positions is key to understanding structural equivalence. Once positions within a certain network are identified, the relations among these positions can be explored. Hanneman and Riddle (2005) describe two types of equivalence in addition to structural equivalence: automorphic equivalence and regular equivalence. If two actors have the exact same relationships to all other actors within a network, these two actors are considered to be structurally equivalent. Automorphic equivalence entails a less strict definition of equivalence. That is, sets of actors can be automorphically equivalent by being positioned in local structures that have the same patterns of ties. For example, assume that both the manager of a sales department and the manager of the human resource department have three employees each. Even though these two managers do not share the same three employees, each has a similar pattern of ties with three employees. Finally, two actors are considered to be regularly equivalent if they have the same pattern of ties with members of other sets of actors who are also regularly equivalent. In other words, actors who are regularly equivalent do not have to fall in the same network positions, but they do have the same types of relationships with members of another set of actors (Hanneman & Riddle).

Social Network Analysis Software

Several software packages for conducting SNA have been developed in recent years. The following list includes software packages that are developed specially for SNA and have their own graphical user interfaces (GUIs): Cytoscape, EgoWeb 2.0, Gephi, KrackPlot, NetMiner, NodeXL, Pajek, SocNetV, StOCNET, and UCINET. Readers should be aware that there are also social network analysis packages designed for programming languages such as R (i.e., a statistical computing software) or Python.

Here is a list of SNA software packages:

Cuttlefish

Cytoscape

EgoWeb 2.0

Gephi

KrackPlot

NetMiner

NodeXL

Pajek

SocNetV

StOCNET

UCINET

Begin the research process by choosing the right problem or topic to explore

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore.

Figure 3.1 Steps for creating research questions.

Problem Selection