- Home

- Sociology of Sport

- Kinesiology/Exercise and Sport Science

- History of Sport

- Sport in America, Volume II

Sport in America, Volume II

From Colonial Leisure to Celebrity Figures and Globalization

Series: Sport in America

464 Pages

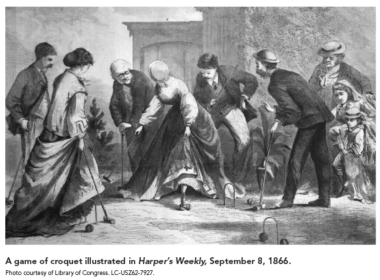

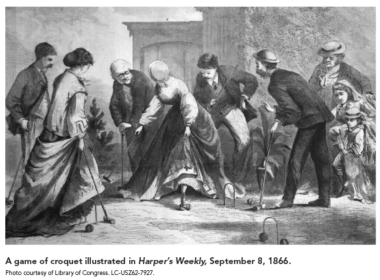

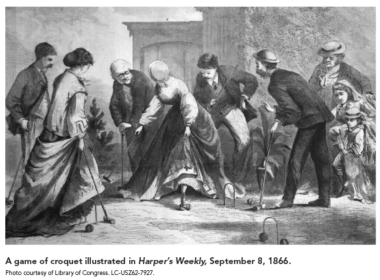

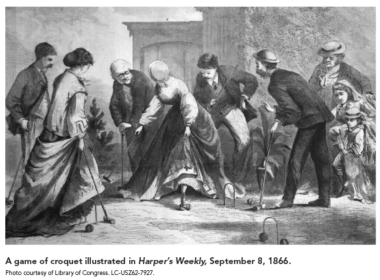

Sport in America: From Colonial Leisure to Celebrity Figures and Globalization, Volume II, presents 18 thought-provoking essays focusing on the changes and patterns in American sport during six distinct eras over the past 400 years. The selections are entirely different from those in the first volume, discussing diverse topics such as views of sport in the Puritan society of colonial New England, gender roles and the croquet craze of the 1800s, and the Super Bowl's place in contemporary sport. Each of the six parts includes an introduction to the essays, allowing readers to relate them to the cultural changes and influences of the period. Readers will find essays on well-known topics written by established scholars as well as new approaches and views from recent studies.

Suitable for use as a stand-alone or supplemental text in undergraduate and graduate sport history courses, Sport in America provides students with opportunities to examine selected sport topics in more depth, realize a greater understanding of sport throughout history, and consider the interrelationships of sport and other societal institutions. Essays are arranged chronologically from the early American period to the present day to provide the proper historical context and offer perspective on changes that have occurred in sport over time. Also, a list of suggested readings provided in each part offers readers the opportunity to expand their thinking on the nature of sport throughout American history.

Essays on how Pinehurst Golf Course was created, the interconnection between sport and the World War I military experience, and discussion of sport icons such as Joe Louis, Walter Camp, Jackie Robinson, and Cal Ripken Jr. allow readers to explore sport as a reflection of the changing values and norms of society. Sport in America: From Colonial Leisure to Celebrity Figures and Globalization, Volume II, provides students and scholars with perspectives regarding the role of sport at particular moments in American history and gives them an appreciation for the complex intersections of sport with society and culture.

Part I: The Pattern of Sport in Early America, 1607-1776

Chapter 1: Sober Mirth and Pleasant Poisons: Puritan Ambivalence Toward Leisure and Recreation in Colonial New England

Bruce C. Daniels

Chapter 2: Horses and Gentlemen: The Cultural Significance of Gambling Among the Gentry of Virginia

T. H. Breen

Part II: Transformation of Sport in a Rapidly Changing Society, 1776-1870

Chapter 3: Pedestrianism, Billiards, Boxing, and Animal Sports

Melvin L. Adelman

Chapter 4: Cheating, Gender Roles, and the Nineteenth-Century Croquet Craze

Jon Sterngass

Chapter 5: The National Game

Warren Goldstein

Part III Sport in the Era of Industrialization and Reform, 1870-1915

Chapter 6: Sporting Life as Consumption, Fashion, and Display—The Pastimes of the Rich

Donald J. Mrozek

Chapter 7: Creating America’s Winter Golfing Mecca at Pinehurst, North Carolina: National Marketing and Local Control

Larry R. Youngs

Chapter 8: The Father of American Football

Michael Oriard

Part IV: Sport, The Great Depression, and Two World Wars, 1915-1950

Chapter 9: The World War I American Military Sporting Experience

S.W. Pope

Chapter 10: In Sports the Best Man Wins: How Joe Louis Whupped Jim Crow

Theresa E. Runstedtler

Chapter 11: Padres on MountOlympus: Los Angeles and the Production of the 1932 Olympic Mega-Event

Sean Dinces

Chapter 12: Going to Bat for Jackie Robinson: The Jewish Role in Breaking Baseball’s Color Line

Stephen H. Norwood and Harold Brackman

Part V: Sport in the Age of Television, Discord, and Personal Fulfillment, 1950-1985

Chapter 13: Toil and Trouble: A Parable of Hard Work and Fun

David W. Zang

Chapter 14: Victory for Allah: Muhammad Ali, the Nation of Islam, and American Society

David K. Wiggins

Chapter 15: The Fight for Title IX

Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackelford

Part VI: Sport During the Period of Celebrity and Globalization, 1985-Present

Chapter 16: Yearning for Yesteryear: Cal Ripken, Jr., The Streak, And the Politics of Nostalgia

Daniel A. Nathan and Mary G. McDonald

Chapter 17: Manhood, Memory, and White Men’s Sports in the American South

Ted Ownby

Chapter 18: The Whole World Isn’t Watching (But We Thought They Were): The Super Bowl and U.S. Solipsism

Christopher R. Martin and Jimmie L. Reeves

About the Editor

David K. Wiggins, PhD, is director of the School of Recreation, Health and Tourism at GeorgeMasonUniversity in Manassas, Virginia. Since earning his PhD from the University of Maryland in 1979, Wiggins has taught undergraduate and graduate courses in sport history at KansasStateUniversity and GeorgeMasonUniversity.

Wiggins is an expert on American sport, particularly as it relates to the involvement of black athletes in sport and physical activity. He has written about sport history since 1980 and published 8 books as well as articles in numerous journals, including Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, Journal of Sport History, Canadian Journal of History of Sport, and International Journal of History of Sport. His work has garnered three Research Writing Awards (1983, 1986, and 1999) from the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (AAHPERD) and significantly affected subsequent research studies on African American involvement in sport.

In addition to his memberships in AAHPERD, the AmericanAcademy of Kinesiology and Physical Education, and the North American Society for Sport History, Wiggins has served as president of the AAHPERDHistoryAcademy, editor of the Journal of Sport History, and history section editor for the Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. Wiggins is currently the editor of Quest.

In his leisure time, Wiggins enjoys reading, playing golf, and walking. He and his wife, Brenda, reside in Fairfax, Virgina, and have two sons, Jordan and Spencer.

Media overstates global appeal of the Super Bowl

The Super Bowl is regarded as one of the most watched sporting events in the world, but statistics prove that is far from true.

The Globalization of the Super Bowl

With the overwhelming dominance of U.S. entertainment content—especially films, television, and music—around the globe, it is no surprise that the National Football League has worked to build a worldwide audience for American football and its premier television event. From the NFL's perspective, it is expanding the market for its product. Don Garber, then senior Vice President of NFL International, explained in 1999: ‘We invest in a long-term plan to help the sport grow around the world. The vision is to be a leading global sport. We need to create awareness and encourage involvement.'

But the desire for global dominance of American football extends beyond just the NFL's profit-oriented interests. As an American cultural ritual, it is increasingly relevant (and increasingly common) that the Super Bowl is represented as the greatest and most watched sporting event on the planet. The enormous, estimated Super Bowl audience of between 800 million and a billion represents at least two competing ideals. On one hand, the Super Bowl's portrayal in mainstream U.S. news media as the leading international sporting event seems to combat post-cold war fragmentation by emphasizing increasing global unity, via a world-wide, shared Super Bowl experience. On the other, it is significant that this international unity is a unity not focused around World Cup soccer (which is football to the majority of the planet), but around American football, a U.S.-controlled export. Herein lies the great solipsism of the Super Bowl. To a large extent, Americans (and their mass media) cannot imagine—or do not wish to—the Super Bowl as being anything less than the biggest, ‘baddest', and best sporting event in the world.

To imagine the Super Bowl as being this top sporting event is to ignore the counter-evidence of several other major sporting events:

- The estimated audience for the soccer World Cup (held every four years) is more than two billion viewers world-wide for the single-day championship match. In 1998 an estimated cumulative audience of 37 billion people watched some of the 64 games over the month-long event.

- The Cricket World Cup, held every four years (most recently in England in 1999) and involving mostly the countries of the former British Empire, has an estimated two billion viewers world-wide, but receives scant attention in the United States.

- Even the Rugby World Cup, also held every four years (most recently in Wales in 1999), claimed 2.5 billion viewers for its 1995 broadcast from South Africa.

- Canada, perhaps the country outside the U.S. most likely to adopt the Super Bowl as its own favorite sporting event—given Canada's geographic proximity, limited language barriers, and familiarity with the NFL, favors its own sports championship. The Grey Cup, the title game of the Canadian Football League, regularly draws three million viewers, more than the annual broadcasts of the Super Bowl and hockey's Stanley Cup final. Only the Academy Awards generate a larger Canadian television audience each year.

For more empirical evidence of the relative global insignificance of American football in general and of the Super Bowl in particular we turn to another manifestation of the post-modern spirit that has transformed the Super Bowl into a carnival of consumption: the CNN World Report (CNNWR). According to corporate legend, CNNWR is Ted Turner's maverick attempt to correct the distortions of American television news coverage of the global scene. Launched on 25 October 1987, CNNWR was designed to provide an alternative vision of global journalism, a vision that transcends the nationalistic framing that contaminates conventional international reporting by the U.S. broadcasting networks. As the program's founding executive producer, Stuart Looring, describes it, Turner's ‘Big Idea' for CNNWR was deceptively simple: ‘Our basic role is to be a huge bulletin board in space on which the world's news organizations can tack up their notices, unedited and uncensored.' But while CNN does not edit nor censor the content of the stories submitted to CNNWR, a few ground rules still apply:

- The report must be in English;

- The report can be no longer than 2 1/2 min;

- It must be understandable.

According to Ralph M. Wenge, current executive producer of CNNWR, ‘the only time we ever work with any of those reports is if somebody has such a strong accent that we can't understand it; then we retrack it in Atlanta.' Furthermore, in providing this unique ‘horizontal news channel', CNN still reserves the right to ‘arrange the individual contributor segment packages into the most appealing sequences for maximum viewer interest.'

Our own sampling of World Report programs suggests that the CNNWR has remained just as ungovernable and diversified and refreshingly deviant as when it was launched. A collection of conventional hard news stories, thinly-veiled propaganda, unpaid advertising for tourist industries, funny animal videos, environmental activism, and insightful cultural features, the metaphor that seem most able to capture the meaning and significance of CNNWR is not a carnival, but a circus. With wild animals, clowns, ring masters, and death defying heroics, the CNNWR is an example of post-modern culture in which all truth is a matter of point-of-view—and the distinctions between high and low, strong and weak, professional and amateur, information and entertainment, First World and Third World, friend and foe, no longer matter.

Using the several key-word searches of the CNNWR Archive, we determined that, if coverage in this post-modern, transnational, news venue is any indication, the Super Bowl is a relatively minor blip on the global sports scene. Here are the results:

- The key words ‘Super' and ‘Bowl' produced only one result. Airing on 22 January 1989, the story was prepared by CNN's own staff and reported on riots that broke out in predominantly black sections of Miami as the city hosted the Super Bowl.

- The key word ‘football' produced 37 results. However, only eight of those stories made any reference to American football. The others were about soccer.

Of the eight American football stories:

- Three were from CNN (the Miami riot story, a story on Thanksgiving football games, and a story on the O.J. Simpson murder scandal).

- Two were from Canada (one about financing stadium construction and one on O.J. Simpson).

- One was from France (about entertaining U.S. servicemen during Operation DESERT SHIELD).

- One was from the Netherlands and one from Finland (both about attempts to introduce American football to the two countries).

By way of comparison, consider the preceding results in relation to key-word searches linked to other sports and sporting events:

- The key words ‘World' and ‘Cup' and ‘soccer' produced 18 results from 12 different countries.

- ‘Hockey' produced 15 results (but ‘Stanley' and ‘Cup' produced zero results).

- ‘Baseball' produced 30 results (and six were related to the World Series).

- ‘Tennis' produced 16 results.

- ‘Basketball' produced 18 results.

- ‘Olympic' produced 164 results from 56 countries.

Clearly, American football occupies a marginal position in the world of sports reported by CNNWR—a position that puts it in roughly the same place on the hierarchy of world sports as cricket (which produced 11 results in the key-word search of the CNNWR Archive).

Imagining That the U.S. is the Center of Attention

Although the Super Bowl holds second-level status among world sporting events, the National Football League and other organizations have actively promoted American football to an international audience at least since the early 1980s. In England in 1982 the then-new Channel 4 joined with the NFL and the U.S. brewing giant Anheuser-Busch to show a weekly edited highlight program of American football. This program (edited versions of a featured game's highlights with flashy graphics and rock and roll music) offered novel programming for Channel 4 and strategic marketing opportunities to develop a British taste for American football and Budweiser beer. (Anheuser-Busch later even established the Budweiser League that organized a competition of local, American-style, football clubs.) Although the size of the television audience for American football in the United Kingdom grew between 1982 and 1990, its popularity peaked in the mid 1980s and leveled off to a little over two millions for the average game audience by 1990, leading the British sport researcher Joe Maguire to conclude that, ‘while American football may be an emergent sport in English society, it certainly has not achieved dominance.'

The first instance of an international audience for the Super Bowl mentioned in the NFL Record and Fact Book on-line is for the year 1985. That Super Bowl, notable for President Reagan doing the game's coin toss shortly after he took his second term oath of office, attracted nearly 116 million viewers in the U.S. The Record and Fact Book also notes that, in addition, ‘six million people watched the Super Bowl in the United Kingdom and a similar number in Italy.' In that same year the NFL adopted a resolution to begin its series of preseason, international, exhibition games, which would field NFL teams in foreign countries to build interest in American football.

In 1986 the Record and Fact Book noted, ‘Super Bowl XX was televised to 59 foreign countries and beamed via satellite to the QE II. An estimated 300 million Chinese viewed a tape delay of the game in March' (more than a month later). The international broadcast remained at about 60 countries for the next several years; but by the end of the cold war the NFL greatly expanded the Super Bowl's reach. In 1993, according to the Record and Fact Book, the game was shown live or taped in 101 countries. However, the data for the numbers of countries and viewers are often wildly reported. For the same 1993 Super Bowl (this one was notable for Michael Jackson's ‘Heal the World' halftime performance), the Los Angeles Times reported that the NFL estimated ‘an audience of more than one billion people in the United States and 86 other countries', USA Weekend noted ‘an estimated one billion viewers in more than 70 countries', and Amusement Business (an industry journal concerned with the halftime program) explained the ‘television audience is estimated at 1.3 billion in 86 countries, which is one reason Jackson agreed to participate.'

By 1999 the estimates of audience size were smaller, but the scope of the international coverage had expanded to include more nations and more languages. The NFL reported that:

Nearly 800 million NFL fans around the world are expected to tune in to watch. International broadcasters will televise the game to at least 180 countries and territories in 24 different languages from Pro Player Stadium: Chinese (Mandarin), Danish, Catalan, Dutch, Norwegian, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian, and Spanish.

In addition, the game will be broadcast in Arabic, Bulgarian, Cantonese, Flemish, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Icelandic, Korean, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Thai, and Turkish. Approximately 90 per cent of the international coverage will be through live telecast of Super Bowl XXXIII.

ERA in Taiwan, RDS (Canada), SAT 1 (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), Sky (United Kingdom), TV-2 (Norway), and TV-2 (Denmark) will be broadcasting on-site for the first time.

On Sunday, 30 January 2000 the Los Angeles Times noted that ‘the game will be broadcast on 225 television stations, 450 radio stations, and in 180 countries. The cliché about a billion people in China not caring is no longer applicable.' Yet the notion that the entire world pauses to pay homage to the Super Bowl is national mythology, continuously constructed via the NFL and the U.S. mass media. As we shall argue below, it is likely that more than a billion people in China do not even have the opportunity to care about the Super Bowl.

The most interesting element of the international audience claims is that the trend (with the exception of 1993—perhaps a top talent like Michael Jackson was expected to draw a larger audience and thus generate record audience estimates) is always upward. This climbing trajectory, of course, is the trend expected of everything connected to the Super Bowl. Yet the growing number of countries receiving the broadcast and the enormous numbers of the estimated or potential audience seem to us to be more of a technical achievement than an indication of popularity. In fact, the record of the NFL's appeal beyond the borders of the United States is mixed. The League's exhibition games overseas have often gone well. For example, the first of the so-called ‘American Bowls' on 3 August 1986 at Wembley Stadium in London (and co-sponsored by the American football booster, Budweiser beer) drew a sell-out crowd of 82,699. The NFL did not take any chances, and scheduled the Super Bowl champions, the Chicago Bears, to play the high-profile Dallas Cowboys in the game (which the Bears won). In August 1994 a record crowd of 112,376 attended an American Bowl game in Mexico City between Dallas and Houston. By 2000, 34 American Bowls had been played in 11 cities outside the U.S., with an average attendance of 58,474.

Although the one-day American Bowl events do well in local attendance, as the fans watch the very best NFL talent, the NFL's attempts to establish international American football leagues have been mediocre at best. In 1991 the NFL created the World League of American Football, which would be the first sports league to operate with teams in North America and Europe, playing on a weekly basis. In 1995, after a two-year hiatus, the WLAF (an acronym with potentially annoying puns for a struggling league) returned to action with just six teams in Europe. On 23 June of that same year the Frankfurt Galaxy defeated the Amsterdam Admirals 26-22, and won the 1995 World Bowl before a crowd of 23,847 in Amsterdam's Olympic Stadium. There were plenty of empty seats there, and the NFL made no claims to a huge world audience for the World Bowl. By the 1998 season the WLAF was renamed the NFL Europe League, which continues to play with six teams. The NFL's international division—formerly founded as NFL International in 1996—continues its efforts to build grass-roots interest in American football through activities such as sponsored flag football leagues in every NFL Europe city and in Japan, Canada, and Mexico. By 2000 NFL International boasted that more than one million children around the world played NFL Flag Football, and counted Canada, Mexico, Australia, and Japan among its ‘priority markets'.

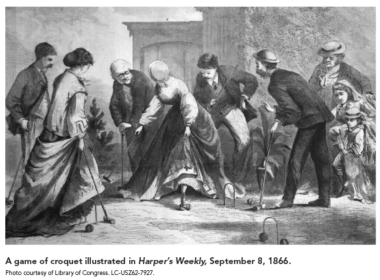

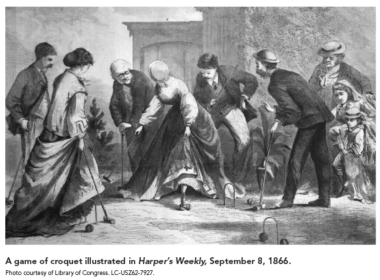

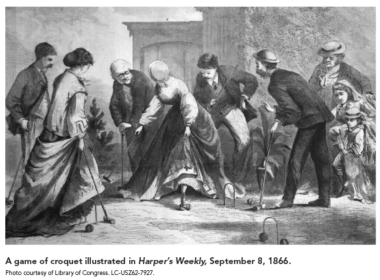

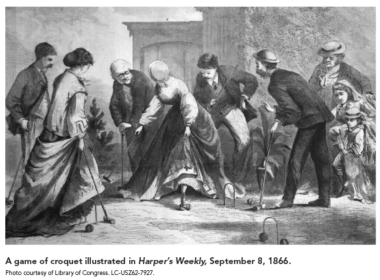

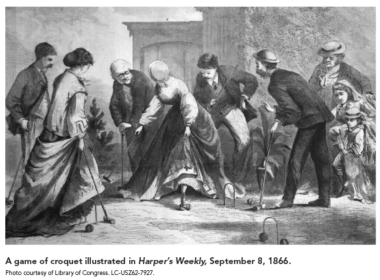

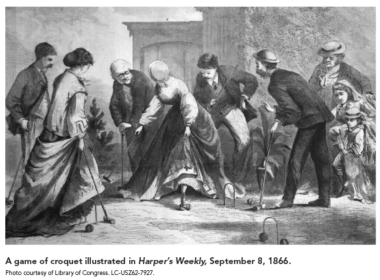

The Nineteenth-Century Croquet Craze

In the nineteenth century, gender roles, cheating, and proper etiquette were greatly influenced by the game of croquet.

Croquet is usually stereotyped as a genteel game, less a sport than a social function, and more suited to genial conversation and unfettered flirtation than strident competition. Nineteenth- century American periodicals and croquet manuals emphasized the sport's placidity, as opposed to male working-class sports such as football, baseball, and rowing, which often seemed infected with the time-discipline or rationality of the workaday world. The Newport (Rhode Island) Croquet Club's 1865 handbook proclaimed that the game owed its popularity to “the delights of out-of-doors exercise and social enjoyment, fresh air and friendship—two things which are of all others most effective for promoting happiness.” Croquet was portrayed as a morally improving and rational recreation; the New York Galaxy declared that “amiability and unselfishness are the first requisites of a good player.” Because croquet was not a particularly athletic game, it was considered ideal for children, older people, and mixed gender groupings. Thus, one recent historian of the sport decisively concluded, “In the 1860s, in a family and female sport like croquet, the etiquette of playing the game with grace and good manners took precedence over winning, sociable play triumphed over unprincipled competition.”

Yet was this, in fact, how the game was played on the croquet lawns of the nineteenth century? While authors of croquet manuals and magazines propounded trite encomiums to honesty, rationality, and fellowship, a perusal of visual and literary evidence reveals that a great deal of competitive spirit existed in the typical croquet match, that the use of deception to win was common, and that women were particularly guilty transgressors. Modern reliance on croquet manuals and a handful of periodical articles recalls the limitations of other nineteenth-century hortatory literature such as etiquette and advice manuals; that is, the ethos was only a code, not an accurate depiction of reality. Female grace and good manners may have been the ideal for the rule- and taste-makers, but on the croquet ground, a peculiar sort of gender reversal enabled women to temporarily jettison their passive role and dominate, if not humiliate, men. Women played the game seriously, enjoyed matching skills with men, and often emerged victorious. The fact that this image runs contrary to “Victorian” gender stereotypes suggests that a more nuanced approach is needed, rather than to declare some sports to be “male” and other sports “female” with all the formulaic and oversimplified preconceptions these adjectives imply.

The rise of boxer Joe Louis

Louis’s well-documented whupping of Jim Crow provided a public outlet for diverse expressions of black struggle across the socioeconomic and political spectrum.

As musicologist Paul Oliver argues, Louis's heroic climb from the cotton fields of Alabama to boxing fame encapsulated the appealing drama and seeming invincibility of traditional African American ballad heroes like John Henry. Indeed, Louis was the only Depression-era athlete that popular blues artists commemorated in recorded songs. As a man who faced the prospect of punishment alone in the ring, he enacted through sport the same kinds of struggles confronting many of his fans. Houston singer Joe Pullman's recording, entitled “Joe Louis is the Man,” was the first song to honor Louis's toppling of Carnera. Although Oliver describes Pullman's creation as a “naïve piece of folk poetry,” it captured the essence of Louis as the archetypal New Negro. While revering the Bomber as “a battlin' man,” it also noted that he was “not a bad dressed guy,” and that even though he was “makin' real good money,” it failed to “swell his head.” Just as Pullman celebrated “powerful Joe” in his performance, the husky-voiced Memphis Minnie McCoy of Chicago recorded “He's in the Ring (Doin' the Same Old Thing)” as a tribute to Louis's two-fisted “dynamite.” The mix of Memphis Minnie's throaty lyrics, her guitar, and Black Bob's pounding piano emphasized the indestructibility of Louis, who knocked out his opponents with remarkable consistency to the delight of his poor and working-class fans. As a rallying point for black communities across the nation, the figure of Louis served to unite the ethereal realm of diasporic politics with the everyday troubles of African Americans.

Louis received a hero's welcome from the black community at Grand Central Station in New York City in the middle of May 1935. As the black press included photos of Louis in chic suits enjoying the finer things in life like driving brand-new cars, he moved beyond his station as prizefighter to become both celebrity and socialite.64 His bodily display of impeccable fashion was one of the most integral aspects of his gendered performance of black pride, since it allowed him to transgress racial norms, moving beyond the ubiquitous black identity of poor worker to showcase his wealth and individuality. One black correspondent praised Louis for looking the part of fistic champion in “his street togs,” while another carefully itemized the boxer's wardrobe of a “dozen suits, nine pairs of shoes, two dozen shirts, 100 neckties, ten hats, six coats and countless sweaters, zippercoats, [and] suits of underwear and pyjamas.” Likewise, newspaper ads for Murray's Pomade, a popular hair straightener, reinforced Louis's reputation for being not only a great fighter but also “one of the best dressed men in America.” As the text of the advertisement claimed, Louis strived to be “well-groomed” both in and out of the ring. The company encouraged the reader to support Louis and to buy their product, since doing both would enable a man to take on the young boxer's power and panache in his everyday life. As the consummate New Negro, Louis reinforced his manhood through his prodigious consumption and street-hip style, offering an optimistic vision of the possibilities of black urban America.

Part politician, part pop idol, and part philanthropist, Louis spent a busy week in the Big Apple meeting with civic leaders like Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia, shaking hands with boxing legends like Jack Dempsey, and attending a series of charity benefits. Trading in his trousers for workout gear four times a day, Louis also starred in a promotional, vaudeville show at the Harlem Opera House, scoring one of the biggest draws in the history of the theater. With a kick-line of pretty dancing girls in the background, he sparred, skipped, and punched the heavy bag to the delight of packed houses. However, the respite was short-lived. With only a month left before the Carnera fight, Louis left for his training camp in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey.

Black correspondents painted an idyllic picture of the countryside estate where Louis prepared for battle, emphasizing its connections to old American gentility, while also touting its modern conveniences. Celebrating Louis's role as the temporary master of the “Big House,” they cloaked him in a mantle of both bourgeois respectability and technological efficiency. According to local lore, George Washington had slept there, and black writers claimed that Louis now occupied the same room where the first president had stayed. Reputedly “one of the most famous fistic training grounds in the world,” the camp was “[n]estled in a nature-scooped nook of the Ramapo Mountains,” yet close enough to the city of Patterson to offer all of the amenities of rural and urban life combined. Although Louis spent most of his days working out, in his few moments of leisure time he supposedly enjoyed freshwater fishing, boating, golfing, and even horseback riding. The training camp itself became an expression of not only Louis's nobility and modernity, but also the dignity and advancement of his people.

Ali's faith large influence on his legacy

The commitment Muhammed Ali had to his Muslim religion brought him strength and confidence that was not normally found in black athletes of his time.

Commitment to Boxing and Faithfulness to the Muslim Religion

The changes in Ali's religious beliefs capped a long spiritual journey marked by steadfast devotion and commitment. Though renowned for his sexual appetite and enjoyment of worldly pleasures, Ali was unwavering in his faithfulness to the Muslim religion and his belief in Allah. He derived strength and a sense of freedom from unquestioning obedience to Muslim leadership and belief in the omnipotence of Allah. His commitment to the Nation of Islam also supported him in his own quest for a sense of identity and racial consciousness. His loyalty to the movement gave him the confidence necessary to express pride in his blackness and the merits of black culture. He shed the humility and accommodating attitude typically associated with black athletes and defiantly rebelled against the limitations imposed by American society.

The Nation of Islam benefited as much from Ali's membership as did the fighter himself. Elijah Muhammad might have preached black separatism, railed against the evils of commercialized sport, and viewed boxing with disdain, but he had recognized the value of having Ali as a member of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad knew that what ultimately set Ali apart from anyone else in history was that he was both a Muslim and the heavyweight champion of the world, a combination that would attract unprecedented attention for the Nation of Islam, act as an uplifting force in America's black community, and cause impassioned responses in a society that placed unremitting faith in the power of sport to break down racial barriers. Ali could be held up as a symbol of unlimited possibilities for black achievement even while he was portrayed as a proud black man who received his basic sustenance from the Muslim religion. He proved invaluable to the Nation of Islam because he encouraged believers to rebel against social oppression and helped to create unity among competing factions.

Ali's importance to the Nation of Islam can be measured to a large extent by his influence on both the black and white communities in this country. His membership in the Nation of Islam, along with the heavyweight championship, elevated him to hero status of almost mythic proportion among many black Americans. Even those blacks who were appalled by the Nation of Islam's extremism and segregationist policies were infused with racial pride because of the champion's boldness in upholding a religion that accused America of everything from crass materialism to racial oppression. By embodying Muslim ideals, triumphing in the ring, and refusing to acquiesce to either the sport establishment or the broader American society, Ali helped invert stereotypes about blacks and inspired members of his race whose daily lives were often filled with drudgery and belittlement. Black Americans of every age group, economic class, political affiliation, and religious denomination were inspired by Ali's refusal to sacrifice his principles when the clash came between individual success in sport and the imperatives of group action.

Although he garnered respect from white Americans for his great boxing skills and even for the courage of his convictions, large segments of the dominant culture were appalled by Ali's membership in a movement that talked of “white devils,” scorned Christianity, refused to fight for their country, and believed in black racial superiority. To many whites, Ali was a traitor, pure and simple, an ingrate who had turned his back on America and joined forces with hate-filled blacks who worshiped an unfamiliar god and refused to abide by the guiding principles of this country. They believed that Ali was a misguided soul who had been taken in by manipulative charlatans interested merely in self-aggrandizement rather than true religion. It was inconceivable to many whites that Ali could criticize a country that had provided him with limitless opportunities and the chance to secure wealth beyond that of ordinary citizens.

The transformation of the Nation of Islam following the death of Elijah Muhammad, along with the winding down of the war in Vietnam, the lessening of racial tensions, and other societal changes, would eventually lead to greater admiration of Ali by members of all races. Refusing to join forces with Louis Farrakhan and other blacks who remained loyal to Nation of Islam policy, Ali adhered to the orthodox Islamic religion adopted by Wallace Muhammad and the World Community of Al-Islam in the West. In so doing, Ali assumed an honored place in the public consciousness and became less threatening to many Americans. Like the World Community of Al-Islam in the West, Ali seemingly evolved from a revolutionary who was intent on promulgating social upheaval to a conservative American more concerned with spiritual salvation than racial confrontation.

The discipline, self-help, and strict moral code Ali was expected to observe as a member of the Nation of Islam would be forcefully transmitted into his new religion. Finding himself in an atmosphere more favorable to African Americans and armed with a transformed religiosity, Ali shed his racism to speak of the brotherhood of man and the power of God. His new religious beliefs did not sit well with blacks who continued to worship at the shrine of Elijah Muhammad, but it was a relatively smooth transition for the heavyweight champion, who realized that the promise of freedom in American society served to diminish the belief in racial separatism. Ali had helped to liberate African Americans psychologically. He now involved himself in the uplifting of all people through the promotion of Islam. For Ali, separatism had given way to integration, devils and saints were now members of both races, and Christians were no longer responsible for all the evils in the world.

Media overstates global appeal of the Super Bowl

The Super Bowl is regarded as one of the most watched sporting events in the world, but statistics prove that is far from true.

The Globalization of the Super Bowl

With the overwhelming dominance of U.S. entertainment content—especially films, television, and music—around the globe, it is no surprise that the National Football League has worked to build a worldwide audience for American football and its premier television event. From the NFL's perspective, it is expanding the market for its product. Don Garber, then senior Vice President of NFL International, explained in 1999: ‘We invest in a long-term plan to help the sport grow around the world. The vision is to be a leading global sport. We need to create awareness and encourage involvement.'

But the desire for global dominance of American football extends beyond just the NFL's profit-oriented interests. As an American cultural ritual, it is increasingly relevant (and increasingly common) that the Super Bowl is represented as the greatest and most watched sporting event on the planet. The enormous, estimated Super Bowl audience of between 800 million and a billion represents at least two competing ideals. On one hand, the Super Bowl's portrayal in mainstream U.S. news media as the leading international sporting event seems to combat post-cold war fragmentation by emphasizing increasing global unity, via a world-wide, shared Super Bowl experience. On the other, it is significant that this international unity is a unity not focused around World Cup soccer (which is football to the majority of the planet), but around American football, a U.S.-controlled export. Herein lies the great solipsism of the Super Bowl. To a large extent, Americans (and their mass media) cannot imagine—or do not wish to—the Super Bowl as being anything less than the biggest, ‘baddest', and best sporting event in the world.

To imagine the Super Bowl as being this top sporting event is to ignore the counter-evidence of several other major sporting events:

- The estimated audience for the soccer World Cup (held every four years) is more than two billion viewers world-wide for the single-day championship match. In 1998 an estimated cumulative audience of 37 billion people watched some of the 64 games over the month-long event.

- The Cricket World Cup, held every four years (most recently in England in 1999) and involving mostly the countries of the former British Empire, has an estimated two billion viewers world-wide, but receives scant attention in the United States.

- Even the Rugby World Cup, also held every four years (most recently in Wales in 1999), claimed 2.5 billion viewers for its 1995 broadcast from South Africa.

- Canada, perhaps the country outside the U.S. most likely to adopt the Super Bowl as its own favorite sporting event—given Canada's geographic proximity, limited language barriers, and familiarity with the NFL, favors its own sports championship. The Grey Cup, the title game of the Canadian Football League, regularly draws three million viewers, more than the annual broadcasts of the Super Bowl and hockey's Stanley Cup final. Only the Academy Awards generate a larger Canadian television audience each year.

For more empirical evidence of the relative global insignificance of American football in general and of the Super Bowl in particular we turn to another manifestation of the post-modern spirit that has transformed the Super Bowl into a carnival of consumption: the CNN World Report (CNNWR). According to corporate legend, CNNWR is Ted Turner's maverick attempt to correct the distortions of American television news coverage of the global scene. Launched on 25 October 1987, CNNWR was designed to provide an alternative vision of global journalism, a vision that transcends the nationalistic framing that contaminates conventional international reporting by the U.S. broadcasting networks. As the program's founding executive producer, Stuart Looring, describes it, Turner's ‘Big Idea' for CNNWR was deceptively simple: ‘Our basic role is to be a huge bulletin board in space on which the world's news organizations can tack up their notices, unedited and uncensored.' But while CNN does not edit nor censor the content of the stories submitted to CNNWR, a few ground rules still apply:

- The report must be in English;

- The report can be no longer than 2 1/2 min;

- It must be understandable.

According to Ralph M. Wenge, current executive producer of CNNWR, ‘the only time we ever work with any of those reports is if somebody has such a strong accent that we can't understand it; then we retrack it in Atlanta.' Furthermore, in providing this unique ‘horizontal news channel', CNN still reserves the right to ‘arrange the individual contributor segment packages into the most appealing sequences for maximum viewer interest.'

Our own sampling of World Report programs suggests that the CNNWR has remained just as ungovernable and diversified and refreshingly deviant as when it was launched. A collection of conventional hard news stories, thinly-veiled propaganda, unpaid advertising for tourist industries, funny animal videos, environmental activism, and insightful cultural features, the metaphor that seem most able to capture the meaning and significance of CNNWR is not a carnival, but a circus. With wild animals, clowns, ring masters, and death defying heroics, the CNNWR is an example of post-modern culture in which all truth is a matter of point-of-view—and the distinctions between high and low, strong and weak, professional and amateur, information and entertainment, First World and Third World, friend and foe, no longer matter.

Using the several key-word searches of the CNNWR Archive, we determined that, if coverage in this post-modern, transnational, news venue is any indication, the Super Bowl is a relatively minor blip on the global sports scene. Here are the results:

- The key words ‘Super' and ‘Bowl' produced only one result. Airing on 22 January 1989, the story was prepared by CNN's own staff and reported on riots that broke out in predominantly black sections of Miami as the city hosted the Super Bowl.

- The key word ‘football' produced 37 results. However, only eight of those stories made any reference to American football. The others were about soccer.

Of the eight American football stories:

- Three were from CNN (the Miami riot story, a story on Thanksgiving football games, and a story on the O.J. Simpson murder scandal).

- Two were from Canada (one about financing stadium construction and one on O.J. Simpson).

- One was from France (about entertaining U.S. servicemen during Operation DESERT SHIELD).

- One was from the Netherlands and one from Finland (both about attempts to introduce American football to the two countries).

By way of comparison, consider the preceding results in relation to key-word searches linked to other sports and sporting events:

- The key words ‘World' and ‘Cup' and ‘soccer' produced 18 results from 12 different countries.

- ‘Hockey' produced 15 results (but ‘Stanley' and ‘Cup' produced zero results).

- ‘Baseball' produced 30 results (and six were related to the World Series).

- ‘Tennis' produced 16 results.

- ‘Basketball' produced 18 results.

- ‘Olympic' produced 164 results from 56 countries.

Clearly, American football occupies a marginal position in the world of sports reported by CNNWR—a position that puts it in roughly the same place on the hierarchy of world sports as cricket (which produced 11 results in the key-word search of the CNNWR Archive).

Imagining That the U.S. is the Center of Attention

Although the Super Bowl holds second-level status among world sporting events, the National Football League and other organizations have actively promoted American football to an international audience at least since the early 1980s. In England in 1982 the then-new Channel 4 joined with the NFL and the U.S. brewing giant Anheuser-Busch to show a weekly edited highlight program of American football. This program (edited versions of a featured game's highlights with flashy graphics and rock and roll music) offered novel programming for Channel 4 and strategic marketing opportunities to develop a British taste for American football and Budweiser beer. (Anheuser-Busch later even established the Budweiser League that organized a competition of local, American-style, football clubs.) Although the size of the television audience for American football in the United Kingdom grew between 1982 and 1990, its popularity peaked in the mid 1980s and leveled off to a little over two millions for the average game audience by 1990, leading the British sport researcher Joe Maguire to conclude that, ‘while American football may be an emergent sport in English society, it certainly has not achieved dominance.'

The first instance of an international audience for the Super Bowl mentioned in the NFL Record and Fact Book on-line is for the year 1985. That Super Bowl, notable for President Reagan doing the game's coin toss shortly after he took his second term oath of office, attracted nearly 116 million viewers in the U.S. The Record and Fact Book also notes that, in addition, ‘six million people watched the Super Bowl in the United Kingdom and a similar number in Italy.' In that same year the NFL adopted a resolution to begin its series of preseason, international, exhibition games, which would field NFL teams in foreign countries to build interest in American football.

In 1986 the Record and Fact Book noted, ‘Super Bowl XX was televised to 59 foreign countries and beamed via satellite to the QE II. An estimated 300 million Chinese viewed a tape delay of the game in March' (more than a month later). The international broadcast remained at about 60 countries for the next several years; but by the end of the cold war the NFL greatly expanded the Super Bowl's reach. In 1993, according to the Record and Fact Book, the game was shown live or taped in 101 countries. However, the data for the numbers of countries and viewers are often wildly reported. For the same 1993 Super Bowl (this one was notable for Michael Jackson's ‘Heal the World' halftime performance), the Los Angeles Times reported that the NFL estimated ‘an audience of more than one billion people in the United States and 86 other countries', USA Weekend noted ‘an estimated one billion viewers in more than 70 countries', and Amusement Business (an industry journal concerned with the halftime program) explained the ‘television audience is estimated at 1.3 billion in 86 countries, which is one reason Jackson agreed to participate.'

By 1999 the estimates of audience size were smaller, but the scope of the international coverage had expanded to include more nations and more languages. The NFL reported that:

Nearly 800 million NFL fans around the world are expected to tune in to watch. International broadcasters will televise the game to at least 180 countries and territories in 24 different languages from Pro Player Stadium: Chinese (Mandarin), Danish, Catalan, Dutch, Norwegian, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian, and Spanish.

In addition, the game will be broadcast in Arabic, Bulgarian, Cantonese, Flemish, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Icelandic, Korean, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Thai, and Turkish. Approximately 90 per cent of the international coverage will be through live telecast of Super Bowl XXXIII.

ERA in Taiwan, RDS (Canada), SAT 1 (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), Sky (United Kingdom), TV-2 (Norway), and TV-2 (Denmark) will be broadcasting on-site for the first time.

On Sunday, 30 January 2000 the Los Angeles Times noted that ‘the game will be broadcast on 225 television stations, 450 radio stations, and in 180 countries. The cliché about a billion people in China not caring is no longer applicable.' Yet the notion that the entire world pauses to pay homage to the Super Bowl is national mythology, continuously constructed via the NFL and the U.S. mass media. As we shall argue below, it is likely that more than a billion people in China do not even have the opportunity to care about the Super Bowl.

The most interesting element of the international audience claims is that the trend (with the exception of 1993—perhaps a top talent like Michael Jackson was expected to draw a larger audience and thus generate record audience estimates) is always upward. This climbing trajectory, of course, is the trend expected of everything connected to the Super Bowl. Yet the growing number of countries receiving the broadcast and the enormous numbers of the estimated or potential audience seem to us to be more of a technical achievement than an indication of popularity. In fact, the record of the NFL's appeal beyond the borders of the United States is mixed. The League's exhibition games overseas have often gone well. For example, the first of the so-called ‘American Bowls' on 3 August 1986 at Wembley Stadium in London (and co-sponsored by the American football booster, Budweiser beer) drew a sell-out crowd of 82,699. The NFL did not take any chances, and scheduled the Super Bowl champions, the Chicago Bears, to play the high-profile Dallas Cowboys in the game (which the Bears won). In August 1994 a record crowd of 112,376 attended an American Bowl game in Mexico City between Dallas and Houston. By 2000, 34 American Bowls had been played in 11 cities outside the U.S., with an average attendance of 58,474.

Although the one-day American Bowl events do well in local attendance, as the fans watch the very best NFL talent, the NFL's attempts to establish international American football leagues have been mediocre at best. In 1991 the NFL created the World League of American Football, which would be the first sports league to operate with teams in North America and Europe, playing on a weekly basis. In 1995, after a two-year hiatus, the WLAF (an acronym with potentially annoying puns for a struggling league) returned to action with just six teams in Europe. On 23 June of that same year the Frankfurt Galaxy defeated the Amsterdam Admirals 26-22, and won the 1995 World Bowl before a crowd of 23,847 in Amsterdam's Olympic Stadium. There were plenty of empty seats there, and the NFL made no claims to a huge world audience for the World Bowl. By the 1998 season the WLAF was renamed the NFL Europe League, which continues to play with six teams. The NFL's international division—formerly founded as NFL International in 1996—continues its efforts to build grass-roots interest in American football through activities such as sponsored flag football leagues in every NFL Europe city and in Japan, Canada, and Mexico. By 2000 NFL International boasted that more than one million children around the world played NFL Flag Football, and counted Canada, Mexico, Australia, and Japan among its ‘priority markets'.

The Nineteenth-Century Croquet Craze

In the nineteenth century, gender roles, cheating, and proper etiquette were greatly influenced by the game of croquet.

Croquet is usually stereotyped as a genteel game, less a sport than a social function, and more suited to genial conversation and unfettered flirtation than strident competition. Nineteenth- century American periodicals and croquet manuals emphasized the sport's placidity, as opposed to male working-class sports such as football, baseball, and rowing, which often seemed infected with the time-discipline or rationality of the workaday world. The Newport (Rhode Island) Croquet Club's 1865 handbook proclaimed that the game owed its popularity to “the delights of out-of-doors exercise and social enjoyment, fresh air and friendship—two things which are of all others most effective for promoting happiness.” Croquet was portrayed as a morally improving and rational recreation; the New York Galaxy declared that “amiability and unselfishness are the first requisites of a good player.” Because croquet was not a particularly athletic game, it was considered ideal for children, older people, and mixed gender groupings. Thus, one recent historian of the sport decisively concluded, “In the 1860s, in a family and female sport like croquet, the etiquette of playing the game with grace and good manners took precedence over winning, sociable play triumphed over unprincipled competition.”

Yet was this, in fact, how the game was played on the croquet lawns of the nineteenth century? While authors of croquet manuals and magazines propounded trite encomiums to honesty, rationality, and fellowship, a perusal of visual and literary evidence reveals that a great deal of competitive spirit existed in the typical croquet match, that the use of deception to win was common, and that women were particularly guilty transgressors. Modern reliance on croquet manuals and a handful of periodical articles recalls the limitations of other nineteenth-century hortatory literature such as etiquette and advice manuals; that is, the ethos was only a code, not an accurate depiction of reality. Female grace and good manners may have been the ideal for the rule- and taste-makers, but on the croquet ground, a peculiar sort of gender reversal enabled women to temporarily jettison their passive role and dominate, if not humiliate, men. Women played the game seriously, enjoyed matching skills with men, and often emerged victorious. The fact that this image runs contrary to “Victorian” gender stereotypes suggests that a more nuanced approach is needed, rather than to declare some sports to be “male” and other sports “female” with all the formulaic and oversimplified preconceptions these adjectives imply.

The rise of boxer Joe Louis

Louis’s well-documented whupping of Jim Crow provided a public outlet for diverse expressions of black struggle across the socioeconomic and political spectrum.

As musicologist Paul Oliver argues, Louis's heroic climb from the cotton fields of Alabama to boxing fame encapsulated the appealing drama and seeming invincibility of traditional African American ballad heroes like John Henry. Indeed, Louis was the only Depression-era athlete that popular blues artists commemorated in recorded songs. As a man who faced the prospect of punishment alone in the ring, he enacted through sport the same kinds of struggles confronting many of his fans. Houston singer Joe Pullman's recording, entitled “Joe Louis is the Man,” was the first song to honor Louis's toppling of Carnera. Although Oliver describes Pullman's creation as a “naïve piece of folk poetry,” it captured the essence of Louis as the archetypal New Negro. While revering the Bomber as “a battlin' man,” it also noted that he was “not a bad dressed guy,” and that even though he was “makin' real good money,” it failed to “swell his head.” Just as Pullman celebrated “powerful Joe” in his performance, the husky-voiced Memphis Minnie McCoy of Chicago recorded “He's in the Ring (Doin' the Same Old Thing)” as a tribute to Louis's two-fisted “dynamite.” The mix of Memphis Minnie's throaty lyrics, her guitar, and Black Bob's pounding piano emphasized the indestructibility of Louis, who knocked out his opponents with remarkable consistency to the delight of his poor and working-class fans. As a rallying point for black communities across the nation, the figure of Louis served to unite the ethereal realm of diasporic politics with the everyday troubles of African Americans.

Louis received a hero's welcome from the black community at Grand Central Station in New York City in the middle of May 1935. As the black press included photos of Louis in chic suits enjoying the finer things in life like driving brand-new cars, he moved beyond his station as prizefighter to become both celebrity and socialite.64 His bodily display of impeccable fashion was one of the most integral aspects of his gendered performance of black pride, since it allowed him to transgress racial norms, moving beyond the ubiquitous black identity of poor worker to showcase his wealth and individuality. One black correspondent praised Louis for looking the part of fistic champion in “his street togs,” while another carefully itemized the boxer's wardrobe of a “dozen suits, nine pairs of shoes, two dozen shirts, 100 neckties, ten hats, six coats and countless sweaters, zippercoats, [and] suits of underwear and pyjamas.” Likewise, newspaper ads for Murray's Pomade, a popular hair straightener, reinforced Louis's reputation for being not only a great fighter but also “one of the best dressed men in America.” As the text of the advertisement claimed, Louis strived to be “well-groomed” both in and out of the ring. The company encouraged the reader to support Louis and to buy their product, since doing both would enable a man to take on the young boxer's power and panache in his everyday life. As the consummate New Negro, Louis reinforced his manhood through his prodigious consumption and street-hip style, offering an optimistic vision of the possibilities of black urban America.

Part politician, part pop idol, and part philanthropist, Louis spent a busy week in the Big Apple meeting with civic leaders like Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia, shaking hands with boxing legends like Jack Dempsey, and attending a series of charity benefits. Trading in his trousers for workout gear four times a day, Louis also starred in a promotional, vaudeville show at the Harlem Opera House, scoring one of the biggest draws in the history of the theater. With a kick-line of pretty dancing girls in the background, he sparred, skipped, and punched the heavy bag to the delight of packed houses. However, the respite was short-lived. With only a month left before the Carnera fight, Louis left for his training camp in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey.

Black correspondents painted an idyllic picture of the countryside estate where Louis prepared for battle, emphasizing its connections to old American gentility, while also touting its modern conveniences. Celebrating Louis's role as the temporary master of the “Big House,” they cloaked him in a mantle of both bourgeois respectability and technological efficiency. According to local lore, George Washington had slept there, and black writers claimed that Louis now occupied the same room where the first president had stayed. Reputedly “one of the most famous fistic training grounds in the world,” the camp was “[n]estled in a nature-scooped nook of the Ramapo Mountains,” yet close enough to the city of Patterson to offer all of the amenities of rural and urban life combined. Although Louis spent most of his days working out, in his few moments of leisure time he supposedly enjoyed freshwater fishing, boating, golfing, and even horseback riding. The training camp itself became an expression of not only Louis's nobility and modernity, but also the dignity and advancement of his people.

Ali's faith large influence on his legacy

The commitment Muhammed Ali had to his Muslim religion brought him strength and confidence that was not normally found in black athletes of his time.

Commitment to Boxing and Faithfulness to the Muslim Religion

The changes in Ali's religious beliefs capped a long spiritual journey marked by steadfast devotion and commitment. Though renowned for his sexual appetite and enjoyment of worldly pleasures, Ali was unwavering in his faithfulness to the Muslim religion and his belief in Allah. He derived strength and a sense of freedom from unquestioning obedience to Muslim leadership and belief in the omnipotence of Allah. His commitment to the Nation of Islam also supported him in his own quest for a sense of identity and racial consciousness. His loyalty to the movement gave him the confidence necessary to express pride in his blackness and the merits of black culture. He shed the humility and accommodating attitude typically associated with black athletes and defiantly rebelled against the limitations imposed by American society.

The Nation of Islam benefited as much from Ali's membership as did the fighter himself. Elijah Muhammad might have preached black separatism, railed against the evils of commercialized sport, and viewed boxing with disdain, but he had recognized the value of having Ali as a member of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad knew that what ultimately set Ali apart from anyone else in history was that he was both a Muslim and the heavyweight champion of the world, a combination that would attract unprecedented attention for the Nation of Islam, act as an uplifting force in America's black community, and cause impassioned responses in a society that placed unremitting faith in the power of sport to break down racial barriers. Ali could be held up as a symbol of unlimited possibilities for black achievement even while he was portrayed as a proud black man who received his basic sustenance from the Muslim religion. He proved invaluable to the Nation of Islam because he encouraged believers to rebel against social oppression and helped to create unity among competing factions.

Ali's importance to the Nation of Islam can be measured to a large extent by his influence on both the black and white communities in this country. His membership in the Nation of Islam, along with the heavyweight championship, elevated him to hero status of almost mythic proportion among many black Americans. Even those blacks who were appalled by the Nation of Islam's extremism and segregationist policies were infused with racial pride because of the champion's boldness in upholding a religion that accused America of everything from crass materialism to racial oppression. By embodying Muslim ideals, triumphing in the ring, and refusing to acquiesce to either the sport establishment or the broader American society, Ali helped invert stereotypes about blacks and inspired members of his race whose daily lives were often filled with drudgery and belittlement. Black Americans of every age group, economic class, political affiliation, and religious denomination were inspired by Ali's refusal to sacrifice his principles when the clash came between individual success in sport and the imperatives of group action.

Although he garnered respect from white Americans for his great boxing skills and even for the courage of his convictions, large segments of the dominant culture were appalled by Ali's membership in a movement that talked of “white devils,” scorned Christianity, refused to fight for their country, and believed in black racial superiority. To many whites, Ali was a traitor, pure and simple, an ingrate who had turned his back on America and joined forces with hate-filled blacks who worshiped an unfamiliar god and refused to abide by the guiding principles of this country. They believed that Ali was a misguided soul who had been taken in by manipulative charlatans interested merely in self-aggrandizement rather than true religion. It was inconceivable to many whites that Ali could criticize a country that had provided him with limitless opportunities and the chance to secure wealth beyond that of ordinary citizens.

The transformation of the Nation of Islam following the death of Elijah Muhammad, along with the winding down of the war in Vietnam, the lessening of racial tensions, and other societal changes, would eventually lead to greater admiration of Ali by members of all races. Refusing to join forces with Louis Farrakhan and other blacks who remained loyal to Nation of Islam policy, Ali adhered to the orthodox Islamic religion adopted by Wallace Muhammad and the World Community of Al-Islam in the West. In so doing, Ali assumed an honored place in the public consciousness and became less threatening to many Americans. Like the World Community of Al-Islam in the West, Ali seemingly evolved from a revolutionary who was intent on promulgating social upheaval to a conservative American more concerned with spiritual salvation than racial confrontation.

The discipline, self-help, and strict moral code Ali was expected to observe as a member of the Nation of Islam would be forcefully transmitted into his new religion. Finding himself in an atmosphere more favorable to African Americans and armed with a transformed religiosity, Ali shed his racism to speak of the brotherhood of man and the power of God. His new religious beliefs did not sit well with blacks who continued to worship at the shrine of Elijah Muhammad, but it was a relatively smooth transition for the heavyweight champion, who realized that the promise of freedom in American society served to diminish the belief in racial separatism. Ali had helped to liberate African Americans psychologically. He now involved himself in the uplifting of all people through the promotion of Islam. For Ali, separatism had given way to integration, devils and saints were now members of both races, and Christians were no longer responsible for all the evils in the world.

Media overstates global appeal of the Super Bowl

The Super Bowl is regarded as one of the most watched sporting events in the world, but statistics prove that is far from true.

The Globalization of the Super Bowl

With the overwhelming dominance of U.S. entertainment content—especially films, television, and music—around the globe, it is no surprise that the National Football League has worked to build a worldwide audience for American football and its premier television event. From the NFL's perspective, it is expanding the market for its product. Don Garber, then senior Vice President of NFL International, explained in 1999: ‘We invest in a long-term plan to help the sport grow around the world. The vision is to be a leading global sport. We need to create awareness and encourage involvement.'

But the desire for global dominance of American football extends beyond just the NFL's profit-oriented interests. As an American cultural ritual, it is increasingly relevant (and increasingly common) that the Super Bowl is represented as the greatest and most watched sporting event on the planet. The enormous, estimated Super Bowl audience of between 800 million and a billion represents at least two competing ideals. On one hand, the Super Bowl's portrayal in mainstream U.S. news media as the leading international sporting event seems to combat post-cold war fragmentation by emphasizing increasing global unity, via a world-wide, shared Super Bowl experience. On the other, it is significant that this international unity is a unity not focused around World Cup soccer (which is football to the majority of the planet), but around American football, a U.S.-controlled export. Herein lies the great solipsism of the Super Bowl. To a large extent, Americans (and their mass media) cannot imagine—or do not wish to—the Super Bowl as being anything less than the biggest, ‘baddest', and best sporting event in the world.

To imagine the Super Bowl as being this top sporting event is to ignore the counter-evidence of several other major sporting events:

- The estimated audience for the soccer World Cup (held every four years) is more than two billion viewers world-wide for the single-day championship match. In 1998 an estimated cumulative audience of 37 billion people watched some of the 64 games over the month-long event.

- The Cricket World Cup, held every four years (most recently in England in 1999) and involving mostly the countries of the former British Empire, has an estimated two billion viewers world-wide, but receives scant attention in the United States.

- Even the Rugby World Cup, also held every four years (most recently in Wales in 1999), claimed 2.5 billion viewers for its 1995 broadcast from South Africa.

- Canada, perhaps the country outside the U.S. most likely to adopt the Super Bowl as its own favorite sporting event—given Canada's geographic proximity, limited language barriers, and familiarity with the NFL, favors its own sports championship. The Grey Cup, the title game of the Canadian Football League, regularly draws three million viewers, more than the annual broadcasts of the Super Bowl and hockey's Stanley Cup final. Only the Academy Awards generate a larger Canadian television audience each year.

For more empirical evidence of the relative global insignificance of American football in general and of the Super Bowl in particular we turn to another manifestation of the post-modern spirit that has transformed the Super Bowl into a carnival of consumption: the CNN World Report (CNNWR). According to corporate legend, CNNWR is Ted Turner's maverick attempt to correct the distortions of American television news coverage of the global scene. Launched on 25 October 1987, CNNWR was designed to provide an alternative vision of global journalism, a vision that transcends the nationalistic framing that contaminates conventional international reporting by the U.S. broadcasting networks. As the program's founding executive producer, Stuart Looring, describes it, Turner's ‘Big Idea' for CNNWR was deceptively simple: ‘Our basic role is to be a huge bulletin board in space on which the world's news organizations can tack up their notices, unedited and uncensored.' But while CNN does not edit nor censor the content of the stories submitted to CNNWR, a few ground rules still apply:

- The report must be in English;

- The report can be no longer than 2 1/2 min;

- It must be understandable.

According to Ralph M. Wenge, current executive producer of CNNWR, ‘the only time we ever work with any of those reports is if somebody has such a strong accent that we can't understand it; then we retrack it in Atlanta.' Furthermore, in providing this unique ‘horizontal news channel', CNN still reserves the right to ‘arrange the individual contributor segment packages into the most appealing sequences for maximum viewer interest.'

Our own sampling of World Report programs suggests that the CNNWR has remained just as ungovernable and diversified and refreshingly deviant as when it was launched. A collection of conventional hard news stories, thinly-veiled propaganda, unpaid advertising for tourist industries, funny animal videos, environmental activism, and insightful cultural features, the metaphor that seem most able to capture the meaning and significance of CNNWR is not a carnival, but a circus. With wild animals, clowns, ring masters, and death defying heroics, the CNNWR is an example of post-modern culture in which all truth is a matter of point-of-view—and the distinctions between high and low, strong and weak, professional and amateur, information and entertainment, First World and Third World, friend and foe, no longer matter.

Using the several key-word searches of the CNNWR Archive, we determined that, if coverage in this post-modern, transnational, news venue is any indication, the Super Bowl is a relatively minor blip on the global sports scene. Here are the results:

- The key words ‘Super' and ‘Bowl' produced only one result. Airing on 22 January 1989, the story was prepared by CNN's own staff and reported on riots that broke out in predominantly black sections of Miami as the city hosted the Super Bowl.

- The key word ‘football' produced 37 results. However, only eight of those stories made any reference to American football. The others were about soccer.

Of the eight American football stories:

- Three were from CNN (the Miami riot story, a story on Thanksgiving football games, and a story on the O.J. Simpson murder scandal).

- Two were from Canada (one about financing stadium construction and one on O.J. Simpson).

- One was from France (about entertaining U.S. servicemen during Operation DESERT SHIELD).

- One was from the Netherlands and one from Finland (both about attempts to introduce American football to the two countries).

By way of comparison, consider the preceding results in relation to key-word searches linked to other sports and sporting events:

- The key words ‘World' and ‘Cup' and ‘soccer' produced 18 results from 12 different countries.

- ‘Hockey' produced 15 results (but ‘Stanley' and ‘Cup' produced zero results).

- ‘Baseball' produced 30 results (and six were related to the World Series).

- ‘Tennis' produced 16 results.

- ‘Basketball' produced 18 results.

- ‘Olympic' produced 164 results from 56 countries.

Clearly, American football occupies a marginal position in the world of sports reported by CNNWR—a position that puts it in roughly the same place on the hierarchy of world sports as cricket (which produced 11 results in the key-word search of the CNNWR Archive).

Imagining That the U.S. is the Center of Attention

Although the Super Bowl holds second-level status among world sporting events, the National Football League and other organizations have actively promoted American football to an international audience at least since the early 1980s. In England in 1982 the then-new Channel 4 joined with the NFL and the U.S. brewing giant Anheuser-Busch to show a weekly edited highlight program of American football. This program (edited versions of a featured game's highlights with flashy graphics and rock and roll music) offered novel programming for Channel 4 and strategic marketing opportunities to develop a British taste for American football and Budweiser beer. (Anheuser-Busch later even established the Budweiser League that organized a competition of local, American-style, football clubs.) Although the size of the television audience for American football in the United Kingdom grew between 1982 and 1990, its popularity peaked in the mid 1980s and leveled off to a little over two millions for the average game audience by 1990, leading the British sport researcher Joe Maguire to conclude that, ‘while American football may be an emergent sport in English society, it certainly has not achieved dominance.'

The first instance of an international audience for the Super Bowl mentioned in the NFL Record and Fact Book on-line is for the year 1985. That Super Bowl, notable for President Reagan doing the game's coin toss shortly after he took his second term oath of office, attracted nearly 116 million viewers in the U.S. The Record and Fact Book also notes that, in addition, ‘six million people watched the Super Bowl in the United Kingdom and a similar number in Italy.' In that same year the NFL adopted a resolution to begin its series of preseason, international, exhibition games, which would field NFL teams in foreign countries to build interest in American football.

In 1986 the Record and Fact Book noted, ‘Super Bowl XX was televised to 59 foreign countries and beamed via satellite to the QE II. An estimated 300 million Chinese viewed a tape delay of the game in March' (more than a month later). The international broadcast remained at about 60 countries for the next several years; but by the end of the cold war the NFL greatly expanded the Super Bowl's reach. In 1993, according to the Record and Fact Book, the game was shown live or taped in 101 countries. However, the data for the numbers of countries and viewers are often wildly reported. For the same 1993 Super Bowl (this one was notable for Michael Jackson's ‘Heal the World' halftime performance), the Los Angeles Times reported that the NFL estimated ‘an audience of more than one billion people in the United States and 86 other countries', USA Weekend noted ‘an estimated one billion viewers in more than 70 countries', and Amusement Business (an industry journal concerned with the halftime program) explained the ‘television audience is estimated at 1.3 billion in 86 countries, which is one reason Jackson agreed to participate.'

By 1999 the estimates of audience size were smaller, but the scope of the international coverage had expanded to include more nations and more languages. The NFL reported that:

Nearly 800 million NFL fans around the world are expected to tune in to watch. International broadcasters will televise the game to at least 180 countries and territories in 24 different languages from Pro Player Stadium: Chinese (Mandarin), Danish, Catalan, Dutch, Norwegian, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian, and Spanish.

In addition, the game will be broadcast in Arabic, Bulgarian, Cantonese, Flemish, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Icelandic, Korean, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Thai, and Turkish. Approximately 90 per cent of the international coverage will be through live telecast of Super Bowl XXXIII.

ERA in Taiwan, RDS (Canada), SAT 1 (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland), Sky (United Kingdom), TV-2 (Norway), and TV-2 (Denmark) will be broadcasting on-site for the first time.

On Sunday, 30 January 2000 the Los Angeles Times noted that ‘the game will be broadcast on 225 television stations, 450 radio stations, and in 180 countries. The cliché about a billion people in China not caring is no longer applicable.' Yet the notion that the entire world pauses to pay homage to the Super Bowl is national mythology, continuously constructed via the NFL and the U.S. mass media. As we shall argue below, it is likely that more than a billion people in China do not even have the opportunity to care about the Super Bowl.

The most interesting element of the international audience claims is that the trend (with the exception of 1993—perhaps a top talent like Michael Jackson was expected to draw a larger audience and thus generate record audience estimates) is always upward. This climbing trajectory, of course, is the trend expected of everything connected to the Super Bowl. Yet the growing number of countries receiving the broadcast and the enormous numbers of the estimated or potential audience seem to us to be more of a technical achievement than an indication of popularity. In fact, the record of the NFL's appeal beyond the borders of the United States is mixed. The League's exhibition games overseas have often gone well. For example, the first of the so-called ‘American Bowls' on 3 August 1986 at Wembley Stadium in London (and co-sponsored by the American football booster, Budweiser beer) drew a sell-out crowd of 82,699. The NFL did not take any chances, and scheduled the Super Bowl champions, the Chicago Bears, to play the high-profile Dallas Cowboys in the game (which the Bears won). In August 1994 a record crowd of 112,376 attended an American Bowl game in Mexico City between Dallas and Houston. By 2000, 34 American Bowls had been played in 11 cities outside the U.S., with an average attendance of 58,474.