- Home

- Sports and Activities

- Sport Management and Sport Business

- Sociology of Sport

- International Sport Management

With a diverse editorial team and assembly of contributors from all corners of the globe, this text presents a truly international perspective and multiple viewpoints on the burgeoning subfield of international sport management. Each chapter showcases how sport operates in various geopolitical environments and cultures, and the text has been updated to address current issues in the industry:

- An engaging new opening chapter on growth in international sport

- A standardized organization of the part II chapters for easier comparison across regions

- A new chapter dedicated to social media in international sport

- New content on corruption and doping in sport, including examples from the Olympics

International Sport Management, Second Edition, introduces students to the structure of governance in international sport and prepares them to apply management strategies in the business segments of sport marketing, sport media and information technology, sport event management, and sport tourism. Case studies and sidebars apply the concepts to real-world situations and demonstrate the challenges and opportunities that future sport managers will face on a regular basis. Instructors will find a suite of ancillaries: a test package, a presentation package, and an instructor guide with tips on incorporating the case studies into the course to maximize the practical learning experience.

With International Sport Management, both practicing and future sport managers will develop an increased understanding of the range of intercultural competencies necessary for success in the field. Using a framework of strategic and total-quality management, the text allows readers to examine global issues from an ethical perspective and uncover solutions to complex challenges that sport managers face. With this approach, readers will learn how to combine business practices with knowledge in international sport to excel in their careers.

Chapter 1. Development of Globally Competent Sport Managers

Michael Pfahl, PhD; Ming Li, EdD; Eric W. MacIntosh, PhD

Key Concepts

Emerging Sports

Emerging Markets

Development of International Competencies for Sport Managers

Summary

Chapter 2. The Globalized Sport Industry: Historical Perspectives

James J. Zhang, PhD; Demetrius W. Pearson, PhD; Tyreal Y. Qian, MS; Euisoo Kim, MBA

Growth of Sport During the Industrial Revolution

Spread of American Sporting Values

International Athletic Arms Race and Militarism

Globalization of Sport in the Late 20th Century

Globalization of the Sporting Goods Industry

International Migration and Sport

Sport Labor Movement

Benefits of International Athletes in Sport Teams and Leagues

Summary

Part II. Field of Play in International Sport

Chapter 3. Sport in North America

Michael Odio, PhD; Shannon Kerwin, PhD

Geographical Description and Demographics

Background and Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 4. Sport in Latin America and the Caribbean

Gonzalo A. Bravo, PhD; Charles Parrish, PhD

Geographical Description and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Economics of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 5. Sport in Western Europe

Brice Lefèvre, PhD; Guillaume Routier, PhD; Guillaume Bodet, PhD

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Economics of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Sport Participation

Summary

Chapter 6. Sport in Eastern Europe

Peter Smolianov, PhD

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance, Management, and Economics of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 7. Sport in Africa

Jepkorir Rose Chepyator-Thomson, PhD; Samuel M. Adodo, PhD; Emma Ariyo, MS

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Economics of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 8. Sport in the Arab World

Mahfoud Amara, PhD

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Economics of Sport

Governance of Sport

Major Sport Events

Management of Sport

Summary

Chapter 9. Sport in Oceania

Trish Bradbury, PhD; Popi Sotiriadou, PhD

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Economics of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 10. Sport in South Asia and Southeast Asia

Megat A. Kamaluddin Megat Daud, PhD; Wirdati M. Radzi, PhD; Govindasamy Balasekaran, PhD

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Economics of Sport

Management of Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Chapter 11. Sport in Northeast Asia

Yong Jae Ko, PhD; Di Xie, PhD; Kazuhiko Kimura, MS

Geographical Description, Demographics, and Background

Role of Sport

Governance of Sport

Professional Sport

Major Sport Events

Summary

Part III. Governance in International Sport

Chapter 12. Olympic and Paralympic Sport

David Legg, PhD; Laura Misener, PhD; Ted Fay, PhD

Formation of the IOC and IPC

Olympic and Paralympic Organization Structure and Governance

Relationships With Outside Stakeholders

History and Commercial Development of the Olympic and Paralympic Games

Considerations for Staging the Games

Social and Ethical Issues in Olympic and Paralympic Sport

Summary

Chapter 13. International Sport Federations

Li Chen, PhD; Chia-Chen Yu, EdD

What Are International Federations?

International Federations and National Federations

Management of International Federations

Summary

Chapter 14. The World Anti-Doping Agency and Ethics in Sport

Clayton Bolton, EdD; Samantha Roberts, PhD

Ethics and Ethical Behavior in Sport

Performance Enhancing Drugs in Sport

World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)

Challenges in the Fight Against PED Use in Sport

Summary

Chapter 15. Professional Sport Leagues and Tours

James Skinner, PhD; Jacqueline Mueller, MS; Steve Swanson, PhD

Structure and Governance

Economic Nature

Revenue Sources

Competition Among Leagues

Summary

Chapter 16. Youth Sport Events and Festivals

Anna-Maria Strittmatter, PhD; Milena M. Parent, PhD

Governance and Stakeholders

Value of Youth Sport Events

Implications for Sport Managers and Researchers

Summary

Part IV. Management Essentials in International Sport

Chapter 17. Intercultural Management in Sport Organizations: The Importance of Human Resource Management

Eric W. MacIntosh, PhD; Gonzalo A. Bravo, PhD

Why Intercultural Management Matters

National Culture

Organizational Culture

Culture Shock and the Role of Human Resources

Employee Socialization

Summary

Chapter 18. Macroeconomics of International Sport

Holger Preuss, PhD; Kevin Heisey, PhD

Role of Sport in a National Economy

Macroeconomic Effects of Sport

Tangible and Intangible Effects

Primary Impact of a Sport Event

Multiplier Effect

Long- and Short-Term Benefits From Sport and the Legacy Effect

Summary

Chapter 19. The Business of International Sport

David J. Shonk, PhD; Doyeon Won, PhD; Ho Keat Leng, PhD

Amateur Participant Sports

Spectator Sports

Summary

Part V. International Sport Business Strategies

Chapter 20. International Sport Marketing

Gashaw Abeza, PhD; Benoit Seguin, PhD

Nature and Unique Aspects of Sport Business

Sport Marketing Basics

Nature of the Professional Sport Team “Product” in a Global Setting

Nature of Sport Consumption

International Sport and Sponsorship

Olympic Brand

Summary

Chapter 21. Digital Media in International Sport

Michael L. Naraine, PhD; Adam J. Karg, PhD

Engagement

Social Media

Fantasy Sport

Future of Digital Media Engagement

Summary

Chapter 22. International Sport Tourism

Kamilla Swart, EdD; Douglas Michele Turco, PhD

Core Principles and Terms

Economic Impact

Social Costs and Benefits

Legacy Effects

Planning and Evaluation

Summary

Part VI. Frontiers and Challenges in International Sport

Chapter 23. Corruption in International Sport

Samantha Roberts, PhD; Clayton Bolton, EdD

Defining Corruption

Types of Corruption

To Cheat or Not to Cheat?

Implications for Stakeholders

Tackling Corruption

Gray Area

Summary

Chapter 24. Corporate Social Responsibility, Sport, and Development

Mitchell McSweeney, MA; Bruce Kidd, PhD; Lyndsay Hayhurst, PhD

Defining Corporate Social Responsibility

Emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport

Understanding Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport

Corporate Social Responsibility, Sport, and International Development

United Nations Global Compact

Summary

Chapter 25. International Sport Management: A Way Forward

Alison Doherty, PhD; Tracy Taylor, PhD

International Sport Management Research Agenda

Conducting International Sport Management Research

Summary

Eric MacIntosh, PhD, is an associate professor of sport management at the University of Ottawa in Canada. MacIntosh researches and teaches on various organizational behavior topics, covering concepts such as culture, leadership, satisfaction, and socialization. His principal research interests are the functioning of the organization and how a favorable culture can transmit positively internally and outwardly into the marketplace.

MacIntosh has consulted for and conducted research with many prominent national and international sport organizations, including the Commonwealth Games Federation, NHL, Right to Play, U Sports, and Youth Olympic Games. He is well published in leading peer-reviewed sport management journals and is a member of several prominent editorial boards.

Gonzalo A. Bravo, PhD, is an associate professor of sport management at West Virginia University in the United States. A native of Santiago, Chile, Bravo has a master’s degree in sport administration from Penn State University and a doctorate in sport management from Ohio State University. Before joining academia, he worked as sport director in a large sport organization in Chile.

His research examines policy and governance aspects of sport as well as organizational behavior in sport. His work has been published in journals such as International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, Managing Sport and Leisure, International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, and the Journal of Sport Management. He is also the coeditor of Sport in Latin America: Policy, Organization, Management (Routledge, 2016) and the author of Sport Mega Events in Emerging Economies (Palgrave, 2018).

He is a founding member of the Latin American Association for Sport Management (ALGEDE) and the Latin American Association of Sociocultural Studies of Sport (ALESDE). In 2016, Bravo completed a sabbatical in Brazil, and from 2014 to 2017 he was a visiting scholar at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Latin American Studies.

Ming Li, EdD, was a professor of sports administration and the chair of the department of sports administration in the College of Business at Ohio University in the United States. Li received his doctorate in sport administration from the University of Kansas.

Li was a former president of the North American Society for Sport Management (NASSM) and served as commissioner of the Commission on Sport Management Accreditation (COSMA). He was a member of the editorial board of Journal of Sport Management and Sport Marketing Quarterly and coauthored two books in sport management. He was a guest professor at six institutions in China, including the Central University of Finance and Economics and Tianjin University of Sport.

Li served as an Olympic envoy for the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. He also served as a consultant for the 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games organizing committee.

Li passed away in 2022.

Engaging fans through social media

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events.

By Michael L. Naraine, PhD, and Adam J. Karg, PhD

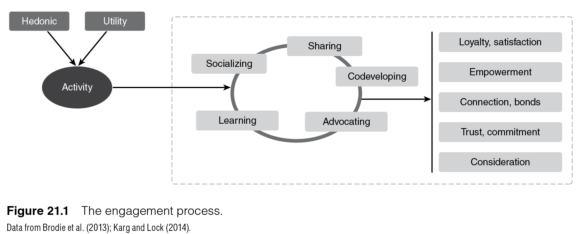

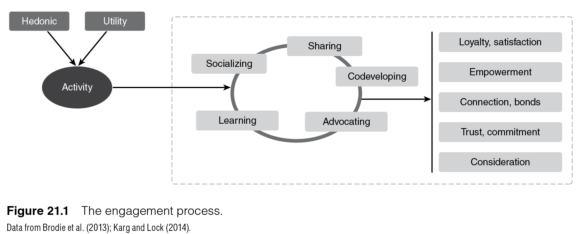

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers' cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events. Related to consumers, engagement sits within an expanded relationship approach to marketing (Vivek et al., 2012) in which consumers are part of interactive relationships with brands, organizations, and each other. Engagement seeks to describe relationships that extend cognition and “encompasses a proactive, interactive customer relationship with a specific engagement object (e.g., a sport brand)” (Brodie et al., 2011, p. 257). Social media and fantasy sport provide examples of digital tools that help harness and develop such relationship using digital engagement tools.

Sport provides a valuable context to explore and observe engagement given inherent aspects that are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature. Sport is often described as a high-involvement service domain, in which part of the role of sport marketers is to leverage commitment and loyalty toward brands using a range of experiences, tools, and exchanges. Therefore, structuring activities to enhance emotional, psychological, and physical investment in brands is a powerful strategy for sport organizations.

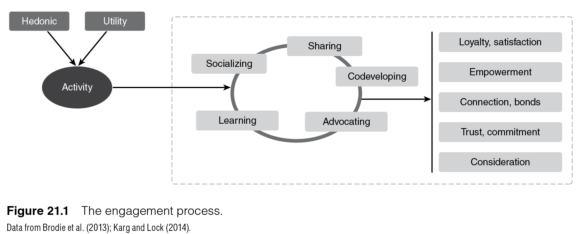

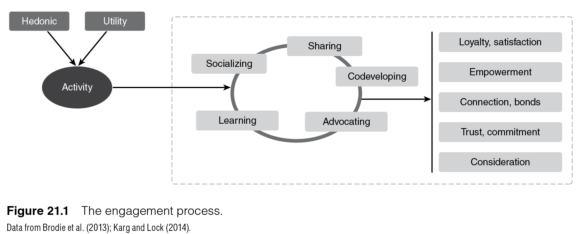

The process of engagement suggests that consumers are motivated by hedonic or utility means to engage in an activity (figure 21.1). From here, a subprocess of engagement that involves sharing, socializing, codeveloping, advocating, and learning is said to develop deeper attitudes, connections, and ultimately relationships within and between consumers and organizations. This chapter will show how both social media and fantasy sport provide ample opportunities to utilize such a subprocess given the design of the tools and exchanges within them.

Consumer engagementprocesses, as well as antecedents and consequences, can help in developing and strengthening interactive relationships. The construct in nonlocalized or international consumer settings has much to offer, in particular when combined with tools such as social media and fantasy sport that are digitalized in nature and available for use at limited additional costs to sport organizations, leagues and events. The chapter seeks to present how these tools have developed and how they can be used to engage fans outside the traditional settings such as match or game attendance. By using digital tools that do not limit consumption to geographic boundaries, sport marketers can seek to develop engagement of fans through digital channels and leverage higher and more developed levels of interaction and consumption between organizations and consumers, and between groups of consumers. In the remaining parts of the chapter, we consider social media and fantasy sport as two such mechanisms, which are widely used in sport to development and leverage engagement.

The role of sport in Eastern Europe

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance.

By Peter Smolianov, PhD

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance. The mechanisms provide lifelong paths in sport from grassroots to professional careers and ensure expertise of all involved with sport, including uniform education; ranks and rewards for participants, coaches, and referees; a pyramidal structure of sport clubs, schools, and universities; and unified plans of amateur and professional competitions. Sport governing organizations in this centralized, integrated, and increasingly democratic system carry difficult responsibilities for equitable spending of state money, ethical achievement of ambitious goals, and enforcement of rules and control over doping and corruption.

Coaches run this sport system because they are employed by the state and rewarded according to achievements of participants. According to the East European notion of sport as preventative medicine, the coaches assume the roles of holistic physicians as well as spiritual leaders, being well educated in biomedical and pedagogical sciences. Coaches receive help from medical doctors and scientists to nurture participants through long-term development process, directing each participant to the sport appropriate for individual health conditions.

Mass fitness, health, fun, and artistic expression had been priorities of sport traditions in Eastern Europe. Competitive festive sport participation by one-third of the USSR population contributed to peaceful socioeconomic progress by means of balancing the stress from work with rich sport, arts, and cultural recreation. In an attempt to introduce more democracy, the government liberated the country's political and economic systems by setting the republics free in 1991 and privatizing public assets, which, regretfully, resulted in the shift of wealth to the elite, a decline in life standards for the majority, and wars among the disintegrated republics, which claimed over 100,000 dead and wounded and over 3 million displaced from their homes.

Preoccupied with a market economy in 1991 through 1999, the government was largely concerned with making sport profitable. As a result Russian sport lost much of its public funding, which caused deterioration in mass participation and in the number of qualified coaches, managers, and scientists. Russian youth were found to be 20 percent less fit in the 1990s than they were in the 1970s, and the country's elite sport performance deteriorated. The capitalist reforms of the 1990s brought a long period of stress and reduced affordable sport and recreation services, which led to an increase in the number of cases of depression, smoking, alcoholism, drug addiction, suicide, antisocial behavior, and crime (Igoshev & Apletin, 2014).

Reforming their economies and political structures, dealing with border issues, and fighting wars, many of the former Soviet republics and Eastern bloc member countries initially reduced their emphasis on sport. In the two decades after 1990, the interaction of sport and society changed dramatically in Eastern Europe as the Soviet bloc dissolved and public resources devoted to mass sport decreased. Following the 1989-1990 political and economic transition, Hungarian sport, like other Eastern European sport systems, had to adapt to new economic and legal circumstances of capitalism, particularly in how sport was financed (Gál, 2012). Bulgaria also found that the transition from a planned to a free-market economy led to a withdrawal of many subsidies and services to sport. At a time when their real incomes were dropping, people could ill afford to pay for sport participation. “Sport for all” changed from a way of life to a matter of choice (Girginov & Bankov, 2002). Similarly, in Romania, after decades of nearly free sport and recreation services and increasing choices of facilities and programs accompanied by noisy propaganda and aggressive ways to encourage sport participation, people found it difficult to devote time and money to sporting recreation, which is now far from a way of life (Suciu et al., 2002). These post-1990 changes had a somewhat negative effect on mass participation and elite sport performance in the former socialist countries.

In the 21st century, the Russian government started to restore political and economic stability, and the quality of life increased because of higher investments in education, health care, and sport. Russia was second in the medal tallies at the 2010 Youth Olympic Games and at the 2011 World Summer Universiade. The Russian Paralympic team moved from 11th place in 2004 to 8th in the 2008 Summer Games, and in the Winter Paralympics the Russian athletes moved from the 5th in 1994 and 1998, to 4th in 2002, and to 1st in 2006 and 2010. Under President Putin's leadership, the mass fitness and international sport programs started to regain their importance after the year 2000. Sport development has been particularly emphasized since 2007 when the Russian city of Sochi won the bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. In 2008 the Russian Sport Ministry was reestablished with a higher status and broader responsibilities, employing 220 administrative staff in the head office and 310,974 coaches and other sport specialists across the country. Physical education was increased from two to three times a week with a revitalized GTO(Ready for Labor and Defense) fitness program in all Russian schools. The Sport Ministry has committed to reach the following goals by 2020:

- Have 40 percent of the overall population, 20 percent of disabled individuals, and 80 percent of students participating in sport.

- Attract everyone to exercise three to four times or 6 to 12 hours a week.

- Ensure that 45 percent of all organizations have sport clubs.

- Employ 360,000 qualified public coaches and other sport professionals.

- Place within the top three in all future Olympics and Paralympics by total medal count.

The goals of winning in the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games and increasing the number of regular sport participants in Russia from 25 million in 2011 to 43 million in 2015 were achieved, and a long-term goal was set to increase sport participation to 70 percent, or 100 million (Sport Ministry, 2012, 2017). The increased investment in sport showed its first positive effects on national health; in 2009 through 2011, for the first time since the capitalist reforms started, the number of Russians diagnosed with alcoholism and drug addiction decreased (Inchenko, 2014).

The World Anti-Doping Agency and ethics in sport

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules.

By Clayton Bolton, EdD, and Samantha Roberts, PhD

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules. We can learn from the lessons of countries failing to realize that their neighbors may not always act properly or tell the truth. For example, in 1938 British prime minister Neville Chamberlain once shouted, “Peace in our time,” under the impression that an elected leader in Germany would somehow operate ethically and keep his word that Germany would not go to war with Great Britain. Soon after, the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, bombed London and the rest of Great Britain on a routine basis. Additionally, months earlier, Hitler had told the world that Jews were not being mistreated and his administration, and indeed an entire country, hid the fact that the Holocaust had begun to ensure that the 1936 Olympic Games, held in the German capital, Berlin, would go ahead with a full international presence.

Scandal and questions regarding ethical decision-making processes in sport are not new. For many years, athletes have been using PEDs (or being fed them without their knowledge), coaches have been rewarding athletes for cheating, and those in positions of power in sporting organizations have been subject to allegations and investigations regarding decisions made and, in some cases, payments taken. Examples range from the awarding of the World Cup to the fall of the likes of Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa, and from the worldwide disgrace of Lance Armstrong to the banning of an entire Russian Olympic team from competition.

It has been said that former Chicago Cubs first baseman Mark Grace was the first to utter the phrase “If you're not cheating, you're not trying hard enough” (Rankin, 2012, para. 1). Said another way, “If you're not first, you're last!” once uttered by fictional character Reese Bobby in a comedy movie about NASCAR, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby(Miller & McKay, 2006). Do we live in an era of “you do what must be done” to be a champion, to finish first, win a gold medal, be famous, be rich? Has the quest for greatness become an all-out assault on cutting corners, taking risks, operating outside the rules, and then lying to cover all tracks of your deception? The idea that fans of the Chicago White Sox baseball team would believe that an illiterate baseball giant from South Carolina would not dare to take money to throw the World Series in 1919, a scandal that ushered in the phrase “Say it ain't so, Joe” (referring to player Shoeless Joe Jackson) seems somewhat normal now. Did eight players on that team actually fix games, and did a rumored gambler from New York, Arnold Rothstein, get away with stealing the World Series in 1919? Yes . . . but does it matter?

“There is no honor among thieves” is an often-used phrase and the title of several novels, movies, and even songs. This concept is acted out in the opening scenes of the movie The Dark Knight(Thomas & Nolan, 2008), when many of the men working for the main villain (The Joker), one by one assassinate the others to gain more of the money, or loot, being stolen from a bank. The idea is that all are interested in simply gaining more for themselves, regardless of the costs or the way in which they get recognition, fame, or the possibility of the financial reward that these days always seems to come with being crowned champion. In contrast, the song “The Champ” (Haynes, Thielk, & Montilla, 2011) by Nelly talks about being a champion of the world based on blood, sweat, and grind as opposed to an unknown or at least unseen competitive advantage—or in so many cases today, an illegal or inappropriate advantage.

Some may ask whether we have reached a point in the world of sport where there is a standard lack of honor among thieves. The authors of this chapter truly hope not, because if we accept that concept, then we must believe that everyone cheats and that no honor remains in sport. Therefore, we must expect that everyone is cheating and the only hope is that we do not get caught.

Engaging fans through social media

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events.

By Michael L. Naraine, PhD, and Adam J. Karg, PhD

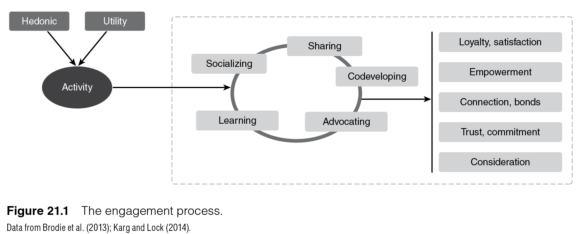

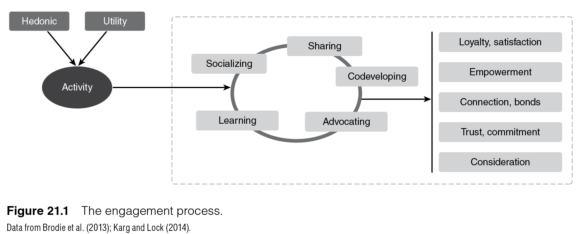

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers' cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events. Related to consumers, engagement sits within an expanded relationship approach to marketing (Vivek et al., 2012) in which consumers are part of interactive relationships with brands, organizations, and each other. Engagement seeks to describe relationships that extend cognition and “encompasses a proactive, interactive customer relationship with a specific engagement object (e.g., a sport brand)” (Brodie et al., 2011, p. 257). Social media and fantasy sport provide examples of digital tools that help harness and develop such relationship using digital engagement tools.

Sport provides a valuable context to explore and observe engagement given inherent aspects that are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature. Sport is often described as a high-involvement service domain, in which part of the role of sport marketers is to leverage commitment and loyalty toward brands using a range of experiences, tools, and exchanges. Therefore, structuring activities to enhance emotional, psychological, and physical investment in brands is a powerful strategy for sport organizations.

The process of engagement suggests that consumers are motivated by hedonic or utility means to engage in an activity (figure 21.1). From here, a subprocess of engagement that involves sharing, socializing, codeveloping, advocating, and learning is said to develop deeper attitudes, connections, and ultimately relationships within and between consumers and organizations. This chapter will show how both social media and fantasy sport provide ample opportunities to utilize such a subprocess given the design of the tools and exchanges within them.

Consumer engagementprocesses, as well as antecedents and consequences, can help in developing and strengthening interactive relationships. The construct in nonlocalized or international consumer settings has much to offer, in particular when combined with tools such as social media and fantasy sport that are digitalized in nature and available for use at limited additional costs to sport organizations, leagues and events. The chapter seeks to present how these tools have developed and how they can be used to engage fans outside the traditional settings such as match or game attendance. By using digital tools that do not limit consumption to geographic boundaries, sport marketers can seek to develop engagement of fans through digital channels and leverage higher and more developed levels of interaction and consumption between organizations and consumers, and between groups of consumers. In the remaining parts of the chapter, we consider social media and fantasy sport as two such mechanisms, which are widely used in sport to development and leverage engagement.

The role of sport in Eastern Europe

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance.

By Peter Smolianov, PhD

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance. The mechanisms provide lifelong paths in sport from grassroots to professional careers and ensure expertise of all involved with sport, including uniform education; ranks and rewards for participants, coaches, and referees; a pyramidal structure of sport clubs, schools, and universities; and unified plans of amateur and professional competitions. Sport governing organizations in this centralized, integrated, and increasingly democratic system carry difficult responsibilities for equitable spending of state money, ethical achievement of ambitious goals, and enforcement of rules and control over doping and corruption.

Coaches run this sport system because they are employed by the state and rewarded according to achievements of participants. According to the East European notion of sport as preventative medicine, the coaches assume the roles of holistic physicians as well as spiritual leaders, being well educated in biomedical and pedagogical sciences. Coaches receive help from medical doctors and scientists to nurture participants through long-term development process, directing each participant to the sport appropriate for individual health conditions.

Mass fitness, health, fun, and artistic expression had been priorities of sport traditions in Eastern Europe. Competitive festive sport participation by one-third of the USSR population contributed to peaceful socioeconomic progress by means of balancing the stress from work with rich sport, arts, and cultural recreation. In an attempt to introduce more democracy, the government liberated the country's political and economic systems by setting the republics free in 1991 and privatizing public assets, which, regretfully, resulted in the shift of wealth to the elite, a decline in life standards for the majority, and wars among the disintegrated republics, which claimed over 100,000 dead and wounded and over 3 million displaced from their homes.

Preoccupied with a market economy in 1991 through 1999, the government was largely concerned with making sport profitable. As a result Russian sport lost much of its public funding, which caused deterioration in mass participation and in the number of qualified coaches, managers, and scientists. Russian youth were found to be 20 percent less fit in the 1990s than they were in the 1970s, and the country's elite sport performance deteriorated. The capitalist reforms of the 1990s brought a long period of stress and reduced affordable sport and recreation services, which led to an increase in the number of cases of depression, smoking, alcoholism, drug addiction, suicide, antisocial behavior, and crime (Igoshev & Apletin, 2014).

Reforming their economies and political structures, dealing with border issues, and fighting wars, many of the former Soviet republics and Eastern bloc member countries initially reduced their emphasis on sport. In the two decades after 1990, the interaction of sport and society changed dramatically in Eastern Europe as the Soviet bloc dissolved and public resources devoted to mass sport decreased. Following the 1989-1990 political and economic transition, Hungarian sport, like other Eastern European sport systems, had to adapt to new economic and legal circumstances of capitalism, particularly in how sport was financed (Gál, 2012). Bulgaria also found that the transition from a planned to a free-market economy led to a withdrawal of many subsidies and services to sport. At a time when their real incomes were dropping, people could ill afford to pay for sport participation. “Sport for all” changed from a way of life to a matter of choice (Girginov & Bankov, 2002). Similarly, in Romania, after decades of nearly free sport and recreation services and increasing choices of facilities and programs accompanied by noisy propaganda and aggressive ways to encourage sport participation, people found it difficult to devote time and money to sporting recreation, which is now far from a way of life (Suciu et al., 2002). These post-1990 changes had a somewhat negative effect on mass participation and elite sport performance in the former socialist countries.

In the 21st century, the Russian government started to restore political and economic stability, and the quality of life increased because of higher investments in education, health care, and sport. Russia was second in the medal tallies at the 2010 Youth Olympic Games and at the 2011 World Summer Universiade. The Russian Paralympic team moved from 11th place in 2004 to 8th in the 2008 Summer Games, and in the Winter Paralympics the Russian athletes moved from the 5th in 1994 and 1998, to 4th in 2002, and to 1st in 2006 and 2010. Under President Putin's leadership, the mass fitness and international sport programs started to regain their importance after the year 2000. Sport development has been particularly emphasized since 2007 when the Russian city of Sochi won the bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. In 2008 the Russian Sport Ministry was reestablished with a higher status and broader responsibilities, employing 220 administrative staff in the head office and 310,974 coaches and other sport specialists across the country. Physical education was increased from two to three times a week with a revitalized GTO(Ready for Labor and Defense) fitness program in all Russian schools. The Sport Ministry has committed to reach the following goals by 2020:

- Have 40 percent of the overall population, 20 percent of disabled individuals, and 80 percent of students participating in sport.

- Attract everyone to exercise three to four times or 6 to 12 hours a week.

- Ensure that 45 percent of all organizations have sport clubs.

- Employ 360,000 qualified public coaches and other sport professionals.

- Place within the top three in all future Olympics and Paralympics by total medal count.

The goals of winning in the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games and increasing the number of regular sport participants in Russia from 25 million in 2011 to 43 million in 2015 were achieved, and a long-term goal was set to increase sport participation to 70 percent, or 100 million (Sport Ministry, 2012, 2017). The increased investment in sport showed its first positive effects on national health; in 2009 through 2011, for the first time since the capitalist reforms started, the number of Russians diagnosed with alcoholism and drug addiction decreased (Inchenko, 2014).

The World Anti-Doping Agency and ethics in sport

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules.

By Clayton Bolton, EdD, and Samantha Roberts, PhD

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules. We can learn from the lessons of countries failing to realize that their neighbors may not always act properly or tell the truth. For example, in 1938 British prime minister Neville Chamberlain once shouted, “Peace in our time,” under the impression that an elected leader in Germany would somehow operate ethically and keep his word that Germany would not go to war with Great Britain. Soon after, the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, bombed London and the rest of Great Britain on a routine basis. Additionally, months earlier, Hitler had told the world that Jews were not being mistreated and his administration, and indeed an entire country, hid the fact that the Holocaust had begun to ensure that the 1936 Olympic Games, held in the German capital, Berlin, would go ahead with a full international presence.

Scandal and questions regarding ethical decision-making processes in sport are not new. For many years, athletes have been using PEDs (or being fed them without their knowledge), coaches have been rewarding athletes for cheating, and those in positions of power in sporting organizations have been subject to allegations and investigations regarding decisions made and, in some cases, payments taken. Examples range from the awarding of the World Cup to the fall of the likes of Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa, and from the worldwide disgrace of Lance Armstrong to the banning of an entire Russian Olympic team from competition.

It has been said that former Chicago Cubs first baseman Mark Grace was the first to utter the phrase “If you're not cheating, you're not trying hard enough” (Rankin, 2012, para. 1). Said another way, “If you're not first, you're last!” once uttered by fictional character Reese Bobby in a comedy movie about NASCAR, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby(Miller & McKay, 2006). Do we live in an era of “you do what must be done” to be a champion, to finish first, win a gold medal, be famous, be rich? Has the quest for greatness become an all-out assault on cutting corners, taking risks, operating outside the rules, and then lying to cover all tracks of your deception? The idea that fans of the Chicago White Sox baseball team would believe that an illiterate baseball giant from South Carolina would not dare to take money to throw the World Series in 1919, a scandal that ushered in the phrase “Say it ain't so, Joe” (referring to player Shoeless Joe Jackson) seems somewhat normal now. Did eight players on that team actually fix games, and did a rumored gambler from New York, Arnold Rothstein, get away with stealing the World Series in 1919? Yes . . . but does it matter?

“There is no honor among thieves” is an often-used phrase and the title of several novels, movies, and even songs. This concept is acted out in the opening scenes of the movie The Dark Knight(Thomas & Nolan, 2008), when many of the men working for the main villain (The Joker), one by one assassinate the others to gain more of the money, or loot, being stolen from a bank. The idea is that all are interested in simply gaining more for themselves, regardless of the costs or the way in which they get recognition, fame, or the possibility of the financial reward that these days always seems to come with being crowned champion. In contrast, the song “The Champ” (Haynes, Thielk, & Montilla, 2011) by Nelly talks about being a champion of the world based on blood, sweat, and grind as opposed to an unknown or at least unseen competitive advantage—or in so many cases today, an illegal or inappropriate advantage.

Some may ask whether we have reached a point in the world of sport where there is a standard lack of honor among thieves. The authors of this chapter truly hope not, because if we accept that concept, then we must believe that everyone cheats and that no honor remains in sport. Therefore, we must expect that everyone is cheating and the only hope is that we do not get caught.

Engaging fans through social media

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events.

By Michael L. Naraine, PhD, and Adam J. Karg, PhD

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers' cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events. Related to consumers, engagement sits within an expanded relationship approach to marketing (Vivek et al., 2012) in which consumers are part of interactive relationships with brands, organizations, and each other. Engagement seeks to describe relationships that extend cognition and “encompasses a proactive, interactive customer relationship with a specific engagement object (e.g., a sport brand)” (Brodie et al., 2011, p. 257). Social media and fantasy sport provide examples of digital tools that help harness and develop such relationship using digital engagement tools.

Sport provides a valuable context to explore and observe engagement given inherent aspects that are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature. Sport is often described as a high-involvement service domain, in which part of the role of sport marketers is to leverage commitment and loyalty toward brands using a range of experiences, tools, and exchanges. Therefore, structuring activities to enhance emotional, psychological, and physical investment in brands is a powerful strategy for sport organizations.

The process of engagement suggests that consumers are motivated by hedonic or utility means to engage in an activity (figure 21.1). From here, a subprocess of engagement that involves sharing, socializing, codeveloping, advocating, and learning is said to develop deeper attitudes, connections, and ultimately relationships within and between consumers and organizations. This chapter will show how both social media and fantasy sport provide ample opportunities to utilize such a subprocess given the design of the tools and exchanges within them.

Consumer engagementprocesses, as well as antecedents and consequences, can help in developing and strengthening interactive relationships. The construct in nonlocalized or international consumer settings has much to offer, in particular when combined with tools such as social media and fantasy sport that are digitalized in nature and available for use at limited additional costs to sport organizations, leagues and events. The chapter seeks to present how these tools have developed and how they can be used to engage fans outside the traditional settings such as match or game attendance. By using digital tools that do not limit consumption to geographic boundaries, sport marketers can seek to develop engagement of fans through digital channels and leverage higher and more developed levels of interaction and consumption between organizations and consumers, and between groups of consumers. In the remaining parts of the chapter, we consider social media and fantasy sport as two such mechanisms, which are widely used in sport to development and leverage engagement.

The role of sport in Eastern Europe

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance.

By Peter Smolianov, PhD

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance. The mechanisms provide lifelong paths in sport from grassroots to professional careers and ensure expertise of all involved with sport, including uniform education; ranks and rewards for participants, coaches, and referees; a pyramidal structure of sport clubs, schools, and universities; and unified plans of amateur and professional competitions. Sport governing organizations in this centralized, integrated, and increasingly democratic system carry difficult responsibilities for equitable spending of state money, ethical achievement of ambitious goals, and enforcement of rules and control over doping and corruption.

Coaches run this sport system because they are employed by the state and rewarded according to achievements of participants. According to the East European notion of sport as preventative medicine, the coaches assume the roles of holistic physicians as well as spiritual leaders, being well educated in biomedical and pedagogical sciences. Coaches receive help from medical doctors and scientists to nurture participants through long-term development process, directing each participant to the sport appropriate for individual health conditions.

Mass fitness, health, fun, and artistic expression had been priorities of sport traditions in Eastern Europe. Competitive festive sport participation by one-third of the USSR population contributed to peaceful socioeconomic progress by means of balancing the stress from work with rich sport, arts, and cultural recreation. In an attempt to introduce more democracy, the government liberated the country's political and economic systems by setting the republics free in 1991 and privatizing public assets, which, regretfully, resulted in the shift of wealth to the elite, a decline in life standards for the majority, and wars among the disintegrated republics, which claimed over 100,000 dead and wounded and over 3 million displaced from their homes.

Preoccupied with a market economy in 1991 through 1999, the government was largely concerned with making sport profitable. As a result Russian sport lost much of its public funding, which caused deterioration in mass participation and in the number of qualified coaches, managers, and scientists. Russian youth were found to be 20 percent less fit in the 1990s than they were in the 1970s, and the country's elite sport performance deteriorated. The capitalist reforms of the 1990s brought a long period of stress and reduced affordable sport and recreation services, which led to an increase in the number of cases of depression, smoking, alcoholism, drug addiction, suicide, antisocial behavior, and crime (Igoshev & Apletin, 2014).

Reforming their economies and political structures, dealing with border issues, and fighting wars, many of the former Soviet republics and Eastern bloc member countries initially reduced their emphasis on sport. In the two decades after 1990, the interaction of sport and society changed dramatically in Eastern Europe as the Soviet bloc dissolved and public resources devoted to mass sport decreased. Following the 1989-1990 political and economic transition, Hungarian sport, like other Eastern European sport systems, had to adapt to new economic and legal circumstances of capitalism, particularly in how sport was financed (Gál, 2012). Bulgaria also found that the transition from a planned to a free-market economy led to a withdrawal of many subsidies and services to sport. At a time when their real incomes were dropping, people could ill afford to pay for sport participation. “Sport for all” changed from a way of life to a matter of choice (Girginov & Bankov, 2002). Similarly, in Romania, after decades of nearly free sport and recreation services and increasing choices of facilities and programs accompanied by noisy propaganda and aggressive ways to encourage sport participation, people found it difficult to devote time and money to sporting recreation, which is now far from a way of life (Suciu et al., 2002). These post-1990 changes had a somewhat negative effect on mass participation and elite sport performance in the former socialist countries.

In the 21st century, the Russian government started to restore political and economic stability, and the quality of life increased because of higher investments in education, health care, and sport. Russia was second in the medal tallies at the 2010 Youth Olympic Games and at the 2011 World Summer Universiade. The Russian Paralympic team moved from 11th place in 2004 to 8th in the 2008 Summer Games, and in the Winter Paralympics the Russian athletes moved from the 5th in 1994 and 1998, to 4th in 2002, and to 1st in 2006 and 2010. Under President Putin's leadership, the mass fitness and international sport programs started to regain their importance after the year 2000. Sport development has been particularly emphasized since 2007 when the Russian city of Sochi won the bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. In 2008 the Russian Sport Ministry was reestablished with a higher status and broader responsibilities, employing 220 administrative staff in the head office and 310,974 coaches and other sport specialists across the country. Physical education was increased from two to three times a week with a revitalized GTO(Ready for Labor and Defense) fitness program in all Russian schools. The Sport Ministry has committed to reach the following goals by 2020:

- Have 40 percent of the overall population, 20 percent of disabled individuals, and 80 percent of students participating in sport.

- Attract everyone to exercise three to four times or 6 to 12 hours a week.

- Ensure that 45 percent of all organizations have sport clubs.

- Employ 360,000 qualified public coaches and other sport professionals.

- Place within the top three in all future Olympics and Paralympics by total medal count.

The goals of winning in the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games and increasing the number of regular sport participants in Russia from 25 million in 2011 to 43 million in 2015 were achieved, and a long-term goal was set to increase sport participation to 70 percent, or 100 million (Sport Ministry, 2012, 2017). The increased investment in sport showed its first positive effects on national health; in 2009 through 2011, for the first time since the capitalist reforms started, the number of Russians diagnosed with alcoholism and drug addiction decreased (Inchenko, 2014).

The World Anti-Doping Agency and ethics in sport

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules.

By Clayton Bolton, EdD, and Samantha Roberts, PhD

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules. We can learn from the lessons of countries failing to realize that their neighbors may not always act properly or tell the truth. For example, in 1938 British prime minister Neville Chamberlain once shouted, “Peace in our time,” under the impression that an elected leader in Germany would somehow operate ethically and keep his word that Germany would not go to war with Great Britain. Soon after, the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, bombed London and the rest of Great Britain on a routine basis. Additionally, months earlier, Hitler had told the world that Jews were not being mistreated and his administration, and indeed an entire country, hid the fact that the Holocaust had begun to ensure that the 1936 Olympic Games, held in the German capital, Berlin, would go ahead with a full international presence.

Scandal and questions regarding ethical decision-making processes in sport are not new. For many years, athletes have been using PEDs (or being fed them without their knowledge), coaches have been rewarding athletes for cheating, and those in positions of power in sporting organizations have been subject to allegations and investigations regarding decisions made and, in some cases, payments taken. Examples range from the awarding of the World Cup to the fall of the likes of Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa, and from the worldwide disgrace of Lance Armstrong to the banning of an entire Russian Olympic team from competition.

It has been said that former Chicago Cubs first baseman Mark Grace was the first to utter the phrase “If you're not cheating, you're not trying hard enough” (Rankin, 2012, para. 1). Said another way, “If you're not first, you're last!” once uttered by fictional character Reese Bobby in a comedy movie about NASCAR, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby(Miller & McKay, 2006). Do we live in an era of “you do what must be done” to be a champion, to finish first, win a gold medal, be famous, be rich? Has the quest for greatness become an all-out assault on cutting corners, taking risks, operating outside the rules, and then lying to cover all tracks of your deception? The idea that fans of the Chicago White Sox baseball team would believe that an illiterate baseball giant from South Carolina would not dare to take money to throw the World Series in 1919, a scandal that ushered in the phrase “Say it ain't so, Joe” (referring to player Shoeless Joe Jackson) seems somewhat normal now. Did eight players on that team actually fix games, and did a rumored gambler from New York, Arnold Rothstein, get away with stealing the World Series in 1919? Yes . . . but does it matter?

“There is no honor among thieves” is an often-used phrase and the title of several novels, movies, and even songs. This concept is acted out in the opening scenes of the movie The Dark Knight(Thomas & Nolan, 2008), when many of the men working for the main villain (The Joker), one by one assassinate the others to gain more of the money, or loot, being stolen from a bank. The idea is that all are interested in simply gaining more for themselves, regardless of the costs or the way in which they get recognition, fame, or the possibility of the financial reward that these days always seems to come with being crowned champion. In contrast, the song “The Champ” (Haynes, Thielk, & Montilla, 2011) by Nelly talks about being a champion of the world based on blood, sweat, and grind as opposed to an unknown or at least unseen competitive advantage—or in so many cases today, an illegal or inappropriate advantage.

Some may ask whether we have reached a point in the world of sport where there is a standard lack of honor among thieves. The authors of this chapter truly hope not, because if we accept that concept, then we must believe that everyone cheats and that no honor remains in sport. Therefore, we must expect that everyone is cheating and the only hope is that we do not get caught.

Engaging fans through social media

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events.

By Michael L. Naraine, PhD, and Adam J. Karg, PhD

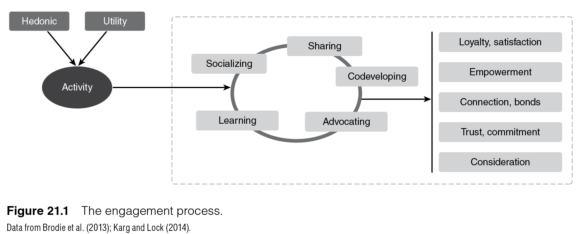

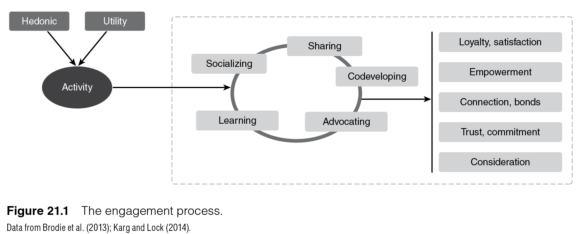

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers' cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events. Related to consumers, engagement sits within an expanded relationship approach to marketing (Vivek et al., 2012) in which consumers are part of interactive relationships with brands, organizations, and each other. Engagement seeks to describe relationships that extend cognition and “encompasses a proactive, interactive customer relationship with a specific engagement object (e.g., a sport brand)” (Brodie et al., 2011, p. 257). Social media and fantasy sport provide examples of digital tools that help harness and develop such relationship using digital engagement tools.

Sport provides a valuable context to explore and observe engagement given inherent aspects that are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature. Sport is often described as a high-involvement service domain, in which part of the role of sport marketers is to leverage commitment and loyalty toward brands using a range of experiences, tools, and exchanges. Therefore, structuring activities to enhance emotional, psychological, and physical investment in brands is a powerful strategy for sport organizations.

The process of engagement suggests that consumers are motivated by hedonic or utility means to engage in an activity (figure 21.1). From here, a subprocess of engagement that involves sharing, socializing, codeveloping, advocating, and learning is said to develop deeper attitudes, connections, and ultimately relationships within and between consumers and organizations. This chapter will show how both social media and fantasy sport provide ample opportunities to utilize such a subprocess given the design of the tools and exchanges within them.

Consumer engagementprocesses, as well as antecedents and consequences, can help in developing and strengthening interactive relationships. The construct in nonlocalized or international consumer settings has much to offer, in particular when combined with tools such as social media and fantasy sport that are digitalized in nature and available for use at limited additional costs to sport organizations, leagues and events. The chapter seeks to present how these tools have developed and how they can be used to engage fans outside the traditional settings such as match or game attendance. By using digital tools that do not limit consumption to geographic boundaries, sport marketers can seek to develop engagement of fans through digital channels and leverage higher and more developed levels of interaction and consumption between organizations and consumers, and between groups of consumers. In the remaining parts of the chapter, we consider social media and fantasy sport as two such mechanisms, which are widely used in sport to development and leverage engagement.

The role of sport in Eastern Europe

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance.

By Peter Smolianov, PhD

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance. The mechanisms provide lifelong paths in sport from grassroots to professional careers and ensure expertise of all involved with sport, including uniform education; ranks and rewards for participants, coaches, and referees; a pyramidal structure of sport clubs, schools, and universities; and unified plans of amateur and professional competitions. Sport governing organizations in this centralized, integrated, and increasingly democratic system carry difficult responsibilities for equitable spending of state money, ethical achievement of ambitious goals, and enforcement of rules and control over doping and corruption.

Coaches run this sport system because they are employed by the state and rewarded according to achievements of participants. According to the East European notion of sport as preventative medicine, the coaches assume the roles of holistic physicians as well as spiritual leaders, being well educated in biomedical and pedagogical sciences. Coaches receive help from medical doctors and scientists to nurture participants through long-term development process, directing each participant to the sport appropriate for individual health conditions.

Mass fitness, health, fun, and artistic expression had been priorities of sport traditions in Eastern Europe. Competitive festive sport participation by one-third of the USSR population contributed to peaceful socioeconomic progress by means of balancing the stress from work with rich sport, arts, and cultural recreation. In an attempt to introduce more democracy, the government liberated the country's political and economic systems by setting the republics free in 1991 and privatizing public assets, which, regretfully, resulted in the shift of wealth to the elite, a decline in life standards for the majority, and wars among the disintegrated republics, which claimed over 100,000 dead and wounded and over 3 million displaced from their homes.

Preoccupied with a market economy in 1991 through 1999, the government was largely concerned with making sport profitable. As a result Russian sport lost much of its public funding, which caused deterioration in mass participation and in the number of qualified coaches, managers, and scientists. Russian youth were found to be 20 percent less fit in the 1990s than they were in the 1970s, and the country's elite sport performance deteriorated. The capitalist reforms of the 1990s brought a long period of stress and reduced affordable sport and recreation services, which led to an increase in the number of cases of depression, smoking, alcoholism, drug addiction, suicide, antisocial behavior, and crime (Igoshev & Apletin, 2014).

Reforming their economies and political structures, dealing with border issues, and fighting wars, many of the former Soviet republics and Eastern bloc member countries initially reduced their emphasis on sport. In the two decades after 1990, the interaction of sport and society changed dramatically in Eastern Europe as the Soviet bloc dissolved and public resources devoted to mass sport decreased. Following the 1989-1990 political and economic transition, Hungarian sport, like other Eastern European sport systems, had to adapt to new economic and legal circumstances of capitalism, particularly in how sport was financed (Gál, 2012). Bulgaria also found that the transition from a planned to a free-market economy led to a withdrawal of many subsidies and services to sport. At a time when their real incomes were dropping, people could ill afford to pay for sport participation. “Sport for all” changed from a way of life to a matter of choice (Girginov & Bankov, 2002). Similarly, in Romania, after decades of nearly free sport and recreation services and increasing choices of facilities and programs accompanied by noisy propaganda and aggressive ways to encourage sport participation, people found it difficult to devote time and money to sporting recreation, which is now far from a way of life (Suciu et al., 2002). These post-1990 changes had a somewhat negative effect on mass participation and elite sport performance in the former socialist countries.

In the 21st century, the Russian government started to restore political and economic stability, and the quality of life increased because of higher investments in education, health care, and sport. Russia was second in the medal tallies at the 2010 Youth Olympic Games and at the 2011 World Summer Universiade. The Russian Paralympic team moved from 11th place in 2004 to 8th in the 2008 Summer Games, and in the Winter Paralympics the Russian athletes moved from the 5th in 1994 and 1998, to 4th in 2002, and to 1st in 2006 and 2010. Under President Putin's leadership, the mass fitness and international sport programs started to regain their importance after the year 2000. Sport development has been particularly emphasized since 2007 when the Russian city of Sochi won the bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. In 2008 the Russian Sport Ministry was reestablished with a higher status and broader responsibilities, employing 220 administrative staff in the head office and 310,974 coaches and other sport specialists across the country. Physical education was increased from two to three times a week with a revitalized GTO(Ready for Labor and Defense) fitness program in all Russian schools. The Sport Ministry has committed to reach the following goals by 2020:

- Have 40 percent of the overall population, 20 percent of disabled individuals, and 80 percent of students participating in sport.

- Attract everyone to exercise three to four times or 6 to 12 hours a week.

- Ensure that 45 percent of all organizations have sport clubs.

- Employ 360,000 qualified public coaches and other sport professionals.

- Place within the top three in all future Olympics and Paralympics by total medal count.

The goals of winning in the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games and increasing the number of regular sport participants in Russia from 25 million in 2011 to 43 million in 2015 were achieved, and a long-term goal was set to increase sport participation to 70 percent, or 100 million (Sport Ministry, 2012, 2017). The increased investment in sport showed its first positive effects on national health; in 2009 through 2011, for the first time since the capitalist reforms started, the number of Russians diagnosed with alcoholism and drug addiction decreased (Inchenko, 2014).

The World Anti-Doping Agency and ethics in sport

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules.

By Clayton Bolton, EdD, and Samantha Roberts, PhD

Maybe it is the flawed thinking and concept of peer accountability. Members of an organization (in our case professional sport, amateur athletics, intercollegiate athletics, and even youth sport) are intended to operate on the understanding that everyone is playing fairly and that each member, team, and individual is abiding by the same rules. We can learn from the lessons of countries failing to realize that their neighbors may not always act properly or tell the truth. For example, in 1938 British prime minister Neville Chamberlain once shouted, “Peace in our time,” under the impression that an elected leader in Germany would somehow operate ethically and keep his word that Germany would not go to war with Great Britain. Soon after, the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, bombed London and the rest of Great Britain on a routine basis. Additionally, months earlier, Hitler had told the world that Jews were not being mistreated and his administration, and indeed an entire country, hid the fact that the Holocaust had begun to ensure that the 1936 Olympic Games, held in the German capital, Berlin, would go ahead with a full international presence.

Scandal and questions regarding ethical decision-making processes in sport are not new. For many years, athletes have been using PEDs (or being fed them without their knowledge), coaches have been rewarding athletes for cheating, and those in positions of power in sporting organizations have been subject to allegations and investigations regarding decisions made and, in some cases, payments taken. Examples range from the awarding of the World Cup to the fall of the likes of Barry Bonds and Sammy Sosa, and from the worldwide disgrace of Lance Armstrong to the banning of an entire Russian Olympic team from competition.

It has been said that former Chicago Cubs first baseman Mark Grace was the first to utter the phrase “If you're not cheating, you're not trying hard enough” (Rankin, 2012, para. 1). Said another way, “If you're not first, you're last!” once uttered by fictional character Reese Bobby in a comedy movie about NASCAR, Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby(Miller & McKay, 2006). Do we live in an era of “you do what must be done” to be a champion, to finish first, win a gold medal, be famous, be rich? Has the quest for greatness become an all-out assault on cutting corners, taking risks, operating outside the rules, and then lying to cover all tracks of your deception? The idea that fans of the Chicago White Sox baseball team would believe that an illiterate baseball giant from South Carolina would not dare to take money to throw the World Series in 1919, a scandal that ushered in the phrase “Say it ain't so, Joe” (referring to player Shoeless Joe Jackson) seems somewhat normal now. Did eight players on that team actually fix games, and did a rumored gambler from New York, Arnold Rothstein, get away with stealing the World Series in 1919? Yes . . . but does it matter?

“There is no honor among thieves” is an often-used phrase and the title of several novels, movies, and even songs. This concept is acted out in the opening scenes of the movie The Dark Knight(Thomas & Nolan, 2008), when many of the men working for the main villain (The Joker), one by one assassinate the others to gain more of the money, or loot, being stolen from a bank. The idea is that all are interested in simply gaining more for themselves, regardless of the costs or the way in which they get recognition, fame, or the possibility of the financial reward that these days always seems to come with being crowned champion. In contrast, the song “The Champ” (Haynes, Thielk, & Montilla, 2011) by Nelly talks about being a champion of the world based on blood, sweat, and grind as opposed to an unknown or at least unseen competitive advantage—or in so many cases today, an illegal or inappropriate advantage.

Some may ask whether we have reached a point in the world of sport where there is a standard lack of honor among thieves. The authors of this chapter truly hope not, because if we accept that concept, then we must believe that everyone cheats and that no honor remains in sport. Therefore, we must expect that everyone is cheating and the only hope is that we do not get caught.

Engaging fans through social media

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers’ cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events.

By Michael L. Naraine, PhD, and Adam J. Karg, PhD

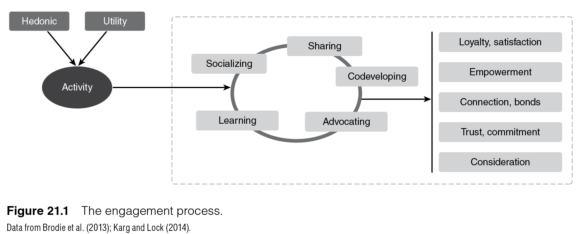

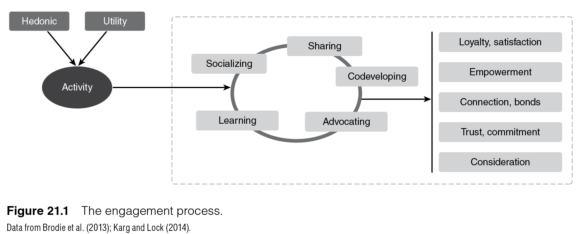

Engagement consists of three interrelated dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011, 2013) in which consumers' cognition, emotions, and behaviors are antecedents for a series of positive outcomes for brands, organizations, and events. Related to consumers, engagement sits within an expanded relationship approach to marketing (Vivek et al., 2012) in which consumers are part of interactive relationships with brands, organizations, and each other. Engagement seeks to describe relationships that extend cognition and “encompasses a proactive, interactive customer relationship with a specific engagement object (e.g., a sport brand)” (Brodie et al., 2011, p. 257). Social media and fantasy sport provide examples of digital tools that help harness and develop such relationship using digital engagement tools.

Sport provides a valuable context to explore and observe engagement given inherent aspects that are emotional, cognitive, and behavioral in nature. Sport is often described as a high-involvement service domain, in which part of the role of sport marketers is to leverage commitment and loyalty toward brands using a range of experiences, tools, and exchanges. Therefore, structuring activities to enhance emotional, psychological, and physical investment in brands is a powerful strategy for sport organizations.

The process of engagement suggests that consumers are motivated by hedonic or utility means to engage in an activity (figure 21.1). From here, a subprocess of engagement that involves sharing, socializing, codeveloping, advocating, and learning is said to develop deeper attitudes, connections, and ultimately relationships within and between consumers and organizations. This chapter will show how both social media and fantasy sport provide ample opportunities to utilize such a subprocess given the design of the tools and exchanges within them.

Consumer engagementprocesses, as well as antecedents and consequences, can help in developing and strengthening interactive relationships. The construct in nonlocalized or international consumer settings has much to offer, in particular when combined with tools such as social media and fantasy sport that are digitalized in nature and available for use at limited additional costs to sport organizations, leagues and events. The chapter seeks to present how these tools have developed and how they can be used to engage fans outside the traditional settings such as match or game attendance. By using digital tools that do not limit consumption to geographic boundaries, sport marketers can seek to develop engagement of fans through digital channels and leverage higher and more developed levels of interaction and consumption between organizations and consumers, and between groups of consumers. In the remaining parts of the chapter, we consider social media and fantasy sport as two such mechanisms, which are widely used in sport to development and leverage engagement.

The role of sport in Eastern Europe

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance.

By Peter Smolianov, PhD

The philosophical and organizational principles inherited by present-day Eastern Europe from the former monarchies of the region and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union continue to guide comprehensive governmental leadership of scientific, educational, and medical support aimed at maximizing mass fitness and elite sport performance. The mechanisms provide lifelong paths in sport from grassroots to professional careers and ensure expertise of all involved with sport, including uniform education; ranks and rewards for participants, coaches, and referees; a pyramidal structure of sport clubs, schools, and universities; and unified plans of amateur and professional competitions. Sport governing organizations in this centralized, integrated, and increasingly democratic system carry difficult responsibilities for equitable spending of state money, ethical achievement of ambitious goals, and enforcement of rules and control over doping and corruption.

Coaches run this sport system because they are employed by the state and rewarded according to achievements of participants. According to the East European notion of sport as preventative medicine, the coaches assume the roles of holistic physicians as well as spiritual leaders, being well educated in biomedical and pedagogical sciences. Coaches receive help from medical doctors and scientists to nurture participants through long-term development process, directing each participant to the sport appropriate for individual health conditions.

Mass fitness, health, fun, and artistic expression had been priorities of sport traditions in Eastern Europe. Competitive festive sport participation by one-third of the USSR population contributed to peaceful socioeconomic progress by means of balancing the stress from work with rich sport, arts, and cultural recreation. In an attempt to introduce more democracy, the government liberated the country's political and economic systems by setting the republics free in 1991 and privatizing public assets, which, regretfully, resulted in the shift of wealth to the elite, a decline in life standards for the majority, and wars among the disintegrated republics, which claimed over 100,000 dead and wounded and over 3 million displaced from their homes.