- Home

- Physical Activity and Health

- Health Education

- Health Care in Exercise and Sport

- Health Care for Special Conditions

- Fitness and Health

- Active Ageing

- NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations

NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations

Edited by Patrick L. Jacobs and NSCA -National Strength & Conditioning Association

528 Pages

The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) has long been at the forefront of aiding aspiring and established exercise professionals in working with clients from special populations, such as children, aging adults, and clients with temporary or permanent physical or cognitive conditions and disorders. Clients with special conditions often require modifications to general exercise recommendations, specific exercise facility design, and particular training equipment. They may also require exercise programming supervised by exercise professionals with specialized training.

NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations will help exercise professionals design customized programs for clients with unique considerations. It is an ideal preparatory resource for those seeking to become an NSCA Certified Special Population Specialist (CSPS) as well as professionals who work in collaboration with health care professionals to assess, educate, and train special population clients of all ages regarding their health and fitness needs. Editor Patrick L. Jacobs, who has extensive experience as both a practitioner and scholar, and a team of qualified contributors provide evidence-based information and recommendations on particular training protocols for a breadth of conditions, including musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular conditions, immunologic disorders, and cancer.

The book discusses the benefits of exercise for clients with special conditions and the exercise-related challenges they often face, as well as the importance of safe and effective health and fitness assessments for these clients. With an emphasis on published research, NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations reviews the pathology and pathophysiology of numerous conditions and disorders, including the known effects of exercise on those conditions and disorders. Each chapter includes tables that provide exercise recommendations for specific conditions, complete with training modifications, precautions, and contraindications. Also included are case studies with practical examples of the application of these population-specific recommendations, as well as a summary of the commonly prescribed medications and their potential effects on exercise responses and adaptations.

NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations includes a number of learning aids designed to assist the reader. Chapter objectives appear at the beginning of each chapter, study questions are at the end of each chapter, key points in easy-to-find boxes summarize important concepts for the reader, and key terms are identified and defined throughout the text. Recommended readings are also provided for readers wishing to learn more about a topic in general or specifically in preparation for the CSPS exam.

For instructors using NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations in a higher education course or for a training symposium, ancillary materials are available to make class preparation easy. The materials are designed to complement the content and assist in its instruction. The ancillaries consist of an instructor's guide, test package, and presentation package plus image bank.

Chapter 1. Rationale and Considerations for Training Special Populations

Patrick L. Jacobs, PhD, CSCS,*D, FNSCA

Chapter 2. Health Appraisal and Fitness Assessments

John F. Graham, MS, CSCS,*D, RSCC*E, FNSCA

Malcolm T. Whitehead, PhD, CSCS

Chapter 3. Musculoskeletal Conditions and Disorders

Carwyn Sharp, PhD, CSCS,*D

Chapter 4. Metabolic Conditions and Disorders

Thomas P. LaFontaine, PhD, CSCS, NSCA-CPT

Jeffrey L. Roitman, EdD

Paul Sorace, MS, CSCS

Chapter 5. Pulmonary Disorders and Conditions

Kenneth W. Rundell, PhD

James M. Smoliga, DVM, PhD, CSCS

Pnina Weiss, MD, FAAP

Chapter 6. Cardiovascular Conditions and Disorders

Ann Marie Swank, PhD, CSCS

Carwyn Sharp, PhD, CSCS,*D

Chapter 7. Immunologic and Hematologic Disorders

Don Melrose, PhD, CSCS,*D

Jay Dawes, PhD, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT*D, FNSCA

Misty Kesterson, EdD, CSCS

Benjamin Reuter, PhD, ATC, CSCS,*D

Chapter 8. Neuromuscular Conditions and Disorders

Patrick L. Jacobs, PhD, CSCS,*D, FNSCA

Stephanie M. Svoboda, MS, DPT, CSCS

Anna Lepeley, PhD, CSCS

Chapter 9. Cognitive Conditions and Disorders

William J. Kraemer, PhD, CSCS,*D, FNSCA

Brett A. Comstock, PhD, CSCS

James E. Clark, MS, CSCS

Chapter 10. Cancer

Alejandro F. San Juan, PhD, PT

Steven J. Fleck, PhD, CSCS, FNSCA

Alejandro Lucia, MD, PhD

Chapter 11. Children and Adolescents

Avery D. Faigenbaum, EdD, CSCS, CSPS, FNSCA

Chapter 12. Older Adults

Wayne L. Westcott, PhD, CSCS

Chapter 13. Female-Specific Conditions

Jill A. Bush, PhD, CSCS,*D

About the NSCA

The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) is the world’s leading organization in the field of sport conditioning. Drawing on the resources and expertise of the most recognized professionals in strength training and conditioning, sport science, performance research, education, and sports medicine, the NSCA is the world’s trusted source of knowledge and training guidelines for coaches, athletes, and tactical operators. The NSCA provides the crucial link between the lab and the field.

About the Editor

Patrick L. Jacobs, PhD, CSCS,*D, is the owner and head coach at Superior Performance. He earned his doctorate in exercise physiology from the University of Miami. He is a Fellow of the National Strength and Conditioning Association and the International Society of Sports Nutrition. He is a licensed athletic trainer (Florida) and a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist.

Jacobs has published many peer-reviewed scientific articles on exercise and nutritional interventions in populations ranging from people with spinal cord injuries to elite athletic competitors. He has coordinated the performance programs of collegiate and professional championship athletes in a variety of sports, including football, baseball, powerlifting, bodybuilding, auto racing, and sailing. He is also an inventor whose name appears on several exercise device patents.

Understanding and recommending exercise for clients with joint replacements

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

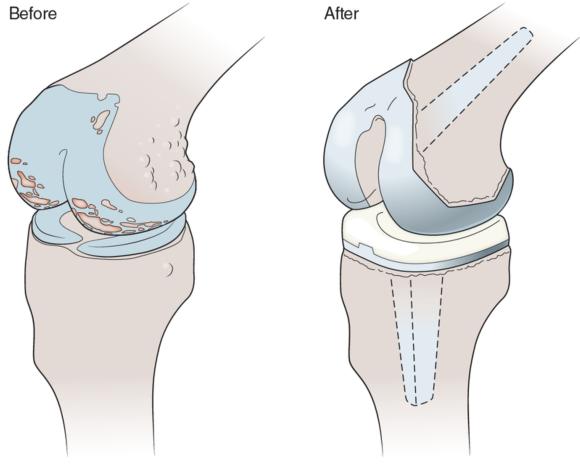

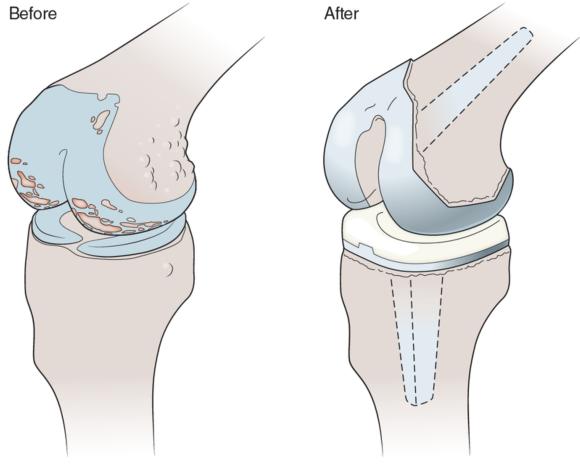

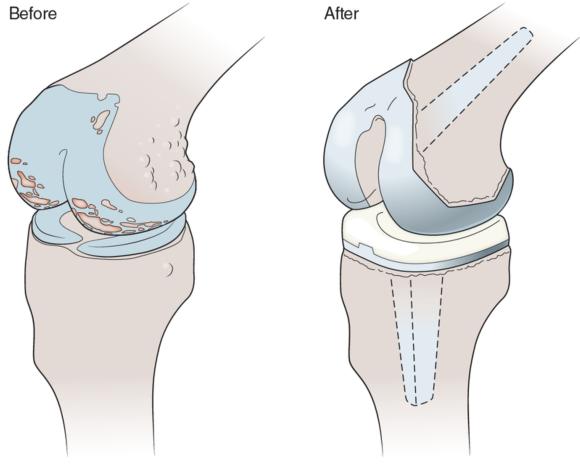

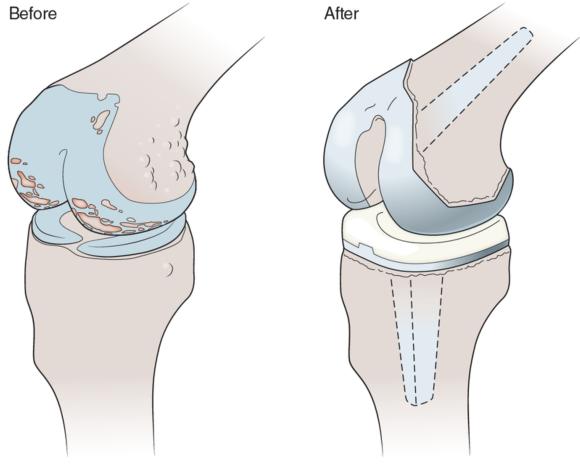

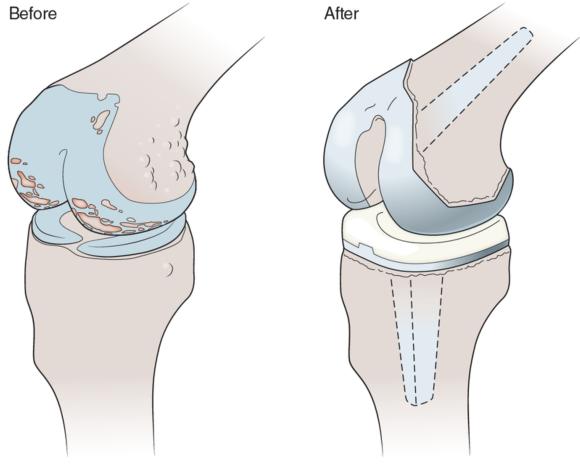

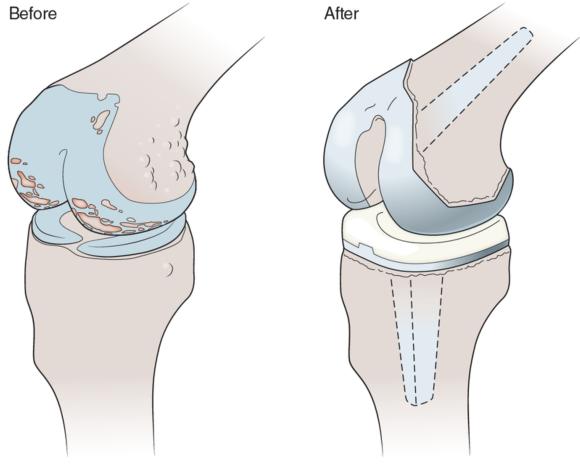

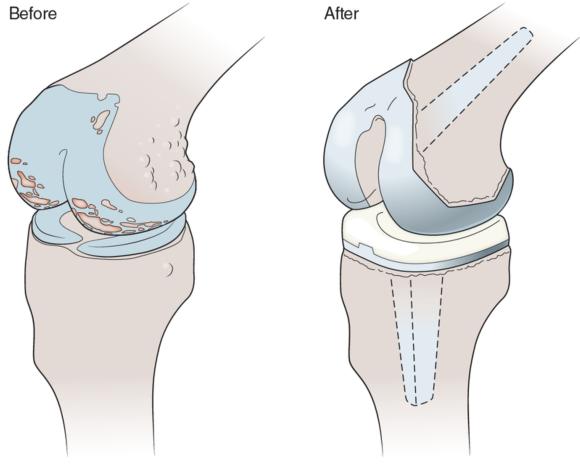

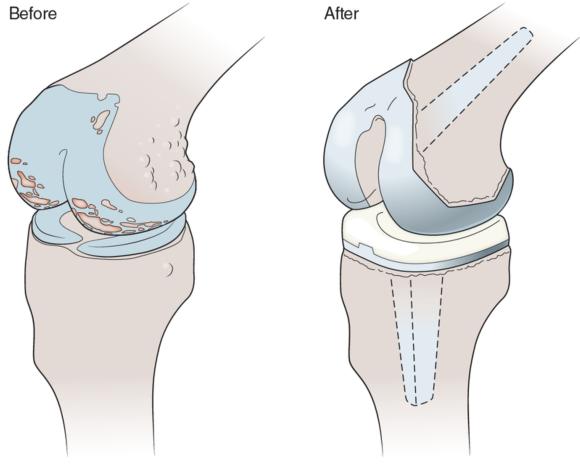

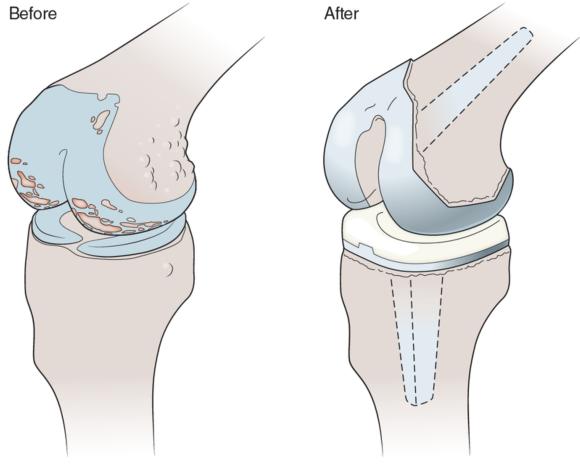

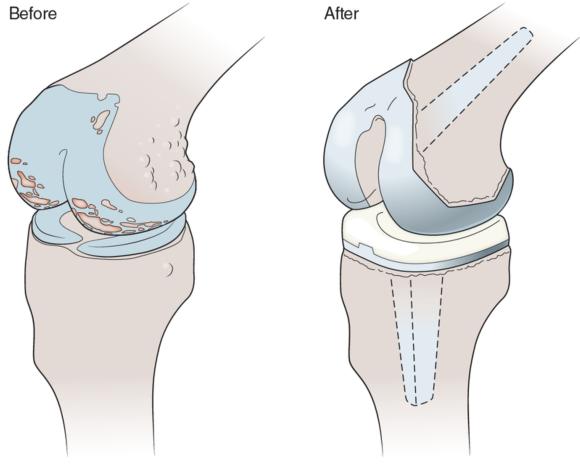

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement (figure 3.7). While total hip and knee replacements are the most common, other joints are also replaced, including, but not limited to, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. In 2011 approximately 1.4 million joint replacement surgeries were performed in the United States, including over 640,000 knee and 300,000 hip total joint replacements. The cumulative number of individuals living in the United States with knee replacements is estimated at over 4 million, with a higher prevalence in females than males and overall prevalence increasing with age. The financial cost of joint replacements was estimated at approximately $16 billion in the United States in 2006 and was projected to rise with the increasing aging population and prevalence of obesity.

Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty) involves replacement of part or all of a damaged joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Pathophysiology of Joint Replacements

Several risk factors leading to joint replacement have been identified; these include age, sex, body mass index, developmental disorders, fractures, injury, and diseases leading to degeneration of one or more aspects of the joint. However, both primary and secondary OA was the principal diagnosis for 85.3% and 97.3% of hip and knee total replacement surgeries, respectively, in the United States in 2011.

Common Medications Given to Individuals With Joint Replacements

Arthroplasty is an invasive procedure, and the medications commonly associated with the surgery include anesthesia, sedatives, intravenous prescription opioid pain relievers (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), and antibiotics. Once the individual is released from the hospital following surgery and acute recovery, various OTC and prescription medications are prescribed (see medications table 3.4 near the end of the chapter). Over-the-counter medication for mild to moderate pain relief (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]) and reducing inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen [Advil]) may be taken for up to several weeks postsurgery; however, as noted earlier, caution is advised as NSAIDs increase the risk of heart attack and stroke with higher doses and longer use. Prescription oral opioid pain relievers may be prescribed for those with more severe pain; however, extended use of these drugs is not recommended because they are highly addictive. Oral antibiotics are also typically prescribed to prophylactically prevent infections, and while side effects are not common, they may include nausea, vomiting, GI distress, or allergic reaction. Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin) are also commonly prescribed because surgery increases the risk of blood clots.

Effects of Exercise in Individuals With Joint Replacements

Postoperative physical activity and exercise to stimulate leg blood flow are encouraged to reduce the risk of blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are strikingly common; 40% to 60% of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients who did not receive antithrombosis treatment had a confirmed postoperative diagnosis.

Key Point

Postoperative physical activity is encouraged in individuals with joint replacements to stimulate leg blood flow and reduce the risk of blood clots. Clearance to exercise from a physician or other health care professional should be obtained prior to initiating exercise.

Exercise Recommendations for Clients With Joint Replacements

Recovery and rehabilitation following joint replacement are highly individualized, as the healing and pain associated with the surgery can last weeks to months, as can the adjustment to the new joint and its movement. During this period of reduced activity, loss of muscle strength will accrue and should be considered and addressed. Initially the client's physician and physical therapist direct the exercise prescription to restore normal and healthy movement patterns and strengthen the joint and associated structures and musculature.

Due to the invasive nature of the surgery, the various types of joint replacement (i.e., partial or total), individualized responses to recovery and rehabilitation, and inconsistencies in the literature, specific exercise prescription is highly individualized. Following the initial recovery and rehabilitation phase, evidence of functionally stable and painless movement patterns of the affected joint is necessary before the client begins a strength and conditioning program. General guidelines for such a program include the following:

- A period of six months is recommended before engaging in vigorous exercise.

- An initial period of low-impact aerobic exercises (i.e., those that combine cyclic low limb movement patterns with low rotational and minimal impact forces) is highly recommended. This includes cycling, swimming, walking, low-impact aerobics, weight training, and cross-country skiing.

- High-impact activities and contact sports should be avoided.

- Exercise and physical activity that include frequent jumping or plyometrics are contraindicated in most cases but should be evaluated individually.

- The client's prior exercise and sporting experience should be considered in these recommendations, as this may indicate an increased tolerance for those activities.

In conjunction it is recommended that exercise professionals refer to the generally accepted guidelines adopted by the U.S. DHHS for developing exercise sessions and programs for adults with joint arthroplasty, while ensuring that the exercise prescription is individualized in its implementation and progression to reflect the limitations, strengths, weaknesses, and goals of the client. The recommendations for a resistance training program are to improve overall muscular strength and endurance; however, a loss of muscle mass may also have occurred, and if so should be addressed. Initial recommendations are two to four sets (one set if the client is sedentary or low in conditioning) of 8 to 12 repetitions per exercise at an initial light to moderate intensity, one or two times per week. To increase flexibility and range of motion it is recommended that clients initially complete static stretches three to seven times per week of all major muscle groups and hold each stretch for 15 to 30 seconds. Recommendations for aerobic exercise are to engage large muscle groups (e.g., brisk walking) at an initial light to moderate intensity for at least 10 minutes three or more times per day, three or more days per week, progressing to at least 300 minutes of moderate or 150 minutes of vigorous (or an equivalent combination of both intensities) per week. Exercise should cease immediately if there is any pain, with referral to a physician or other health care professional. Program design guidelines for clients with joint replacements are summarized in table 3.6.

Save

Save

Save

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Professional opportunities for those training special populations

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area.

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area. Various special populations are expected to grow in size with the increasing rate of inactivity in the general population compounded with specific growth in certain special populations. Almost one-half of all U.S. adults (117 million) have at least one chronic medical condition (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis), with more than two chronic conditions reported in over one-quarter of adults (60 million). The current number of Americans over the age of 65 is calculated at over 40 million and is expected to increase to approximately 72 million persons by the year 2030. Because chronic conditions increase in prevalence in older populations, these figures indicate that an overwhelming number of persons in our society and a growing segment of our society will be classified as a part of special populations.

Health care costs associated with obesity and sedentary lifestyles are greater than $90 billion annually in the United States alone. These escalating costs place undue stress on both individual and employer health insurance systems. The medical system has made dramatic advances in the care of persons with disease, in particular in the area of emergency care. Survival and recovery have significantly improved in many conditions considered to have questionable outcomes only a few decades ago. This dramatically extended life expectancy, from 66 years in males and 71.7 years in females in 1950 to 72.1 years in males and 79.0 years in females in 1990. By the year 2009, the predicted life span from birth had grown to 76.0 years for men and to 80.9 years for women. Thus, during the same period of time in which length of life increased by approximately 10 years, our society became increasingly inactive. This has resulted in progressive extension of the length of life (quantity of life) with significant reductions in the level of functional independence during the later years of life (quality of life).

The medical system may be an important referral source of new clients to the exercise professional with expertise with special populations. Chapter 2 of this text provides detailed discussions of the health appraisal process and the steps to determine the appropriateness of a medical clearance for a particular potential client. The medical clearance process establishes a means of communication between the exercise professional and a licensed health care professional. Medical clearance provides professional authorization for exercise testing and training in persons who exhibit particular risk factors. This process may also establish a line of communication between the exercise professional and the medical professionals with regard to future patients and their need to engage in purposeful exercise programming outside of the medical treatment environment.

Discharge plans from medical care, particularly physical therapy, usually involve some recommendations for activities and exercise strategies for the patient. Patients may have a limited background in exercise and active lifestyles, and their only experience in these areas may be the therapeutic activities in the rehabilitative setting. Thus, it is unlikely that they will seek to begin a structured exercise program with professional support even if this has been recommended by the clinician. It is recommended that the exercise professional establish working relationships with medical professionals in the community. In this way, the patient can be directly referred by the medical professional to an associated exercise professional who can provide the appropriate guidance and supervision.

Unfortunately, in many situations the rehabilitation plan must be carried out with time limitations related to the patient's medical insurance coverage. The therapeutic plan of care often must concentrate on the most vital skills of daily living in order to enhance the level of functional independence in the limited time available. Thus, many patients are discharged from the rehabilitation setting in a condition that warrants continued physical training. Exercise professionals with advanced background in training of special populations can certainly provide the needed assessment and training of these discharged patients, with clearance and recommendations from the clinician.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Case study: client with fibromyalgia

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records.

Case Study

- Sex: Female

- Race: Caucasian

- Age: 43

- Height: 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m)

- Weight: 145 pounds (66 kg)

- Body fat: 32%

- Body mass index: 25.7

- Resting heart rate: 72 beats/min

- Blood pressure: 142/94 mmHg

- Temperature: Normal

History

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records. For several years she has noticed diffuse muscle discomfort throughout her upper body and thighs. She has made several modifications to her workstation to help alleviate her issues, but this has been unsuccessful. Her physical discomfort has made working quite difficult as well as straining her relationships at home. Following a serious car accident, she noticed a marked increase in her symptoms and great difficulty sleeping. After minimal success with physical therapy, she was diagnosed with FM by her primary physician. The physician prescribed NSAIDs, antidepressants, and a sleep aid. Having attempted alternative forms of treatment, Mrs. P sought the help of an exercise professional who was knowledgeable about FM.

Goals

Mrs. P hopes to work with her exercise professional to reach the following goals:

- Alleviate consistent muscular pain

- Improve quality of work and home life

- Establish exercise programming as a regular part of treatment

- Improve overall fitness

Initial Training

Having received clearance from her primary physician, Mrs. P met with a certified exercise specialist at a facility near her home. The exercise professional took a full medical history. Traditional submaximal aerobic and muscular exercise testing was attempted, but results were not accurate due to Mrs. P's low physical capacity. As an alternative, the exercise specialist performed the University of Houston Non-Exercise Test to assess her aerobic capacity and a dynamometer battery consisting of handgrip strength and back and leg strength. Body composition was measured using bioelectric impedance. The exercise professional recommended a slow but progressive approach to achieving a regular exercise program for Mrs. P and recommended a progressive resistance training program, flexibility training, and regimen of cardiopulmonary exercise. Ultimately, the exercise program will need to become a regular part of Mrs. P's treatment plan. It was also recommended that she seek the counsel of a registered dietician to help promote better general health.

Exercise Progression

Resistance training began with a combination of 8 to 10 movements consisting of both bodyweight and resistance band exercises, two days per week. One set of 10 to 15 repetitions was performed for each exercise. While 1- to 2-minute rest periods were appropriate, early training rest periods were variable. Each session was completed with light full-body static stretching. Each stretch was held for 10 to 15 seconds. Aerobic sessions were scheduled on days in which resistance training was not done. Because of Mrs. P's preference, aerobic training was conducted twice per week in a swimming pool. Her group instructor aided her in completion of one or two 5- or 10-minute intervals of activity. All early training was kept below the point of volitional fatigue.

Resistance training frequency was increased to three or four times per week. While repetitions remained in the 10 to 15 range, the number of sets was increased to two or three. To accommodate this change, different muscle groups were trained on different days. Aerobic training progressed from intervals to single sessions of 20 to 30 minutes, three or four days per week. The client also began to explore other aerobic modes. Her training schedule remained flexible and was adjusted as needed depending on her symptoms.

Outcomes

Following some minor setbacks as she learned her exercise tolerances, Mrs. P was able to establish a routine that fit within the structure of her life. Her physical condition improved, as did her quality of life. The combination of her therapies and dietary modifications has been effective. Although she still deals with pain, it is dramatically less than before. The strain on her home and work relationships is better.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Understanding and recommending exercise for clients with joint replacements

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement (figure 3.7). While total hip and knee replacements are the most common, other joints are also replaced, including, but not limited to, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. In 2011 approximately 1.4 million joint replacement surgeries were performed in the United States, including over 640,000 knee and 300,000 hip total joint replacements. The cumulative number of individuals living in the United States with knee replacements is estimated at over 4 million, with a higher prevalence in females than males and overall prevalence increasing with age. The financial cost of joint replacements was estimated at approximately $16 billion in the United States in 2006 and was projected to rise with the increasing aging population and prevalence of obesity.

Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty) involves replacement of part or all of a damaged joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Pathophysiology of Joint Replacements

Several risk factors leading to joint replacement have been identified; these include age, sex, body mass index, developmental disorders, fractures, injury, and diseases leading to degeneration of one or more aspects of the joint. However, both primary and secondary OA was the principal diagnosis for 85.3% and 97.3% of hip and knee total replacement surgeries, respectively, in the United States in 2011.

Common Medications Given to Individuals With Joint Replacements

Arthroplasty is an invasive procedure, and the medications commonly associated with the surgery include anesthesia, sedatives, intravenous prescription opioid pain relievers (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), and antibiotics. Once the individual is released from the hospital following surgery and acute recovery, various OTC and prescription medications are prescribed (see medications table 3.4 near the end of the chapter). Over-the-counter medication for mild to moderate pain relief (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]) and reducing inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen [Advil]) may be taken for up to several weeks postsurgery; however, as noted earlier, caution is advised as NSAIDs increase the risk of heart attack and stroke with higher doses and longer use. Prescription oral opioid pain relievers may be prescribed for those with more severe pain; however, extended use of these drugs is not recommended because they are highly addictive. Oral antibiotics are also typically prescribed to prophylactically prevent infections, and while side effects are not common, they may include nausea, vomiting, GI distress, or allergic reaction. Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin) are also commonly prescribed because surgery increases the risk of blood clots.

Effects of Exercise in Individuals With Joint Replacements

Postoperative physical activity and exercise to stimulate leg blood flow are encouraged to reduce the risk of blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are strikingly common; 40% to 60% of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients who did not receive antithrombosis treatment had a confirmed postoperative diagnosis.

Key Point

Postoperative physical activity is encouraged in individuals with joint replacements to stimulate leg blood flow and reduce the risk of blood clots. Clearance to exercise from a physician or other health care professional should be obtained prior to initiating exercise.

Exercise Recommendations for Clients With Joint Replacements

Recovery and rehabilitation following joint replacement are highly individualized, as the healing and pain associated with the surgery can last weeks to months, as can the adjustment to the new joint and its movement. During this period of reduced activity, loss of muscle strength will accrue and should be considered and addressed. Initially the client's physician and physical therapist direct the exercise prescription to restore normal and healthy movement patterns and strengthen the joint and associated structures and musculature.

Due to the invasive nature of the surgery, the various types of joint replacement (i.e., partial or total), individualized responses to recovery and rehabilitation, and inconsistencies in the literature, specific exercise prescription is highly individualized. Following the initial recovery and rehabilitation phase, evidence of functionally stable and painless movement patterns of the affected joint is necessary before the client begins a strength and conditioning program. General guidelines for such a program include the following:

- A period of six months is recommended before engaging in vigorous exercise.

- An initial period of low-impact aerobic exercises (i.e., those that combine cyclic low limb movement patterns with low rotational and minimal impact forces) is highly recommended. This includes cycling, swimming, walking, low-impact aerobics, weight training, and cross-country skiing.

- High-impact activities and contact sports should be avoided.

- Exercise and physical activity that include frequent jumping or plyometrics are contraindicated in most cases but should be evaluated individually.

- The client's prior exercise and sporting experience should be considered in these recommendations, as this may indicate an increased tolerance for those activities.

In conjunction it is recommended that exercise professionals refer to the generally accepted guidelines adopted by the U.S. DHHS for developing exercise sessions and programs for adults with joint arthroplasty, while ensuring that the exercise prescription is individualized in its implementation and progression to reflect the limitations, strengths, weaknesses, and goals of the client. The recommendations for a resistance training program are to improve overall muscular strength and endurance; however, a loss of muscle mass may also have occurred, and if so should be addressed. Initial recommendations are two to four sets (one set if the client is sedentary or low in conditioning) of 8 to 12 repetitions per exercise at an initial light to moderate intensity, one or two times per week. To increase flexibility and range of motion it is recommended that clients initially complete static stretches three to seven times per week of all major muscle groups and hold each stretch for 15 to 30 seconds. Recommendations for aerobic exercise are to engage large muscle groups (e.g., brisk walking) at an initial light to moderate intensity for at least 10 minutes three or more times per day, three or more days per week, progressing to at least 300 minutes of moderate or 150 minutes of vigorous (or an equivalent combination of both intensities) per week. Exercise should cease immediately if there is any pain, with referral to a physician or other health care professional. Program design guidelines for clients with joint replacements are summarized in table 3.6.

Save

Save

Save

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Professional opportunities for those training special populations

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area.

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area. Various special populations are expected to grow in size with the increasing rate of inactivity in the general population compounded with specific growth in certain special populations. Almost one-half of all U.S. adults (117 million) have at least one chronic medical condition (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis), with more than two chronic conditions reported in over one-quarter of adults (60 million). The current number of Americans over the age of 65 is calculated at over 40 million and is expected to increase to approximately 72 million persons by the year 2030. Because chronic conditions increase in prevalence in older populations, these figures indicate that an overwhelming number of persons in our society and a growing segment of our society will be classified as a part of special populations.

Health care costs associated with obesity and sedentary lifestyles are greater than $90 billion annually in the United States alone. These escalating costs place undue stress on both individual and employer health insurance systems. The medical system has made dramatic advances in the care of persons with disease, in particular in the area of emergency care. Survival and recovery have significantly improved in many conditions considered to have questionable outcomes only a few decades ago. This dramatically extended life expectancy, from 66 years in males and 71.7 years in females in 1950 to 72.1 years in males and 79.0 years in females in 1990. By the year 2009, the predicted life span from birth had grown to 76.0 years for men and to 80.9 years for women. Thus, during the same period of time in which length of life increased by approximately 10 years, our society became increasingly inactive. This has resulted in progressive extension of the length of life (quantity of life) with significant reductions in the level of functional independence during the later years of life (quality of life).

The medical system may be an important referral source of new clients to the exercise professional with expertise with special populations. Chapter 2 of this text provides detailed discussions of the health appraisal process and the steps to determine the appropriateness of a medical clearance for a particular potential client. The medical clearance process establishes a means of communication between the exercise professional and a licensed health care professional. Medical clearance provides professional authorization for exercise testing and training in persons who exhibit particular risk factors. This process may also establish a line of communication between the exercise professional and the medical professionals with regard to future patients and their need to engage in purposeful exercise programming outside of the medical treatment environment.

Discharge plans from medical care, particularly physical therapy, usually involve some recommendations for activities and exercise strategies for the patient. Patients may have a limited background in exercise and active lifestyles, and their only experience in these areas may be the therapeutic activities in the rehabilitative setting. Thus, it is unlikely that they will seek to begin a structured exercise program with professional support even if this has been recommended by the clinician. It is recommended that the exercise professional establish working relationships with medical professionals in the community. In this way, the patient can be directly referred by the medical professional to an associated exercise professional who can provide the appropriate guidance and supervision.

Unfortunately, in many situations the rehabilitation plan must be carried out with time limitations related to the patient's medical insurance coverage. The therapeutic plan of care often must concentrate on the most vital skills of daily living in order to enhance the level of functional independence in the limited time available. Thus, many patients are discharged from the rehabilitation setting in a condition that warrants continued physical training. Exercise professionals with advanced background in training of special populations can certainly provide the needed assessment and training of these discharged patients, with clearance and recommendations from the clinician.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Case study: client with fibromyalgia

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records.

Case Study

- Sex: Female

- Race: Caucasian

- Age: 43

- Height: 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m)

- Weight: 145 pounds (66 kg)

- Body fat: 32%

- Body mass index: 25.7

- Resting heart rate: 72 beats/min

- Blood pressure: 142/94 mmHg

- Temperature: Normal

History

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records. For several years she has noticed diffuse muscle discomfort throughout her upper body and thighs. She has made several modifications to her workstation to help alleviate her issues, but this has been unsuccessful. Her physical discomfort has made working quite difficult as well as straining her relationships at home. Following a serious car accident, she noticed a marked increase in her symptoms and great difficulty sleeping. After minimal success with physical therapy, she was diagnosed with FM by her primary physician. The physician prescribed NSAIDs, antidepressants, and a sleep aid. Having attempted alternative forms of treatment, Mrs. P sought the help of an exercise professional who was knowledgeable about FM.

Goals

Mrs. P hopes to work with her exercise professional to reach the following goals:

- Alleviate consistent muscular pain

- Improve quality of work and home life

- Establish exercise programming as a regular part of treatment

- Improve overall fitness

Initial Training

Having received clearance from her primary physician, Mrs. P met with a certified exercise specialist at a facility near her home. The exercise professional took a full medical history. Traditional submaximal aerobic and muscular exercise testing was attempted, but results were not accurate due to Mrs. P's low physical capacity. As an alternative, the exercise specialist performed the University of Houston Non-Exercise Test to assess her aerobic capacity and a dynamometer battery consisting of handgrip strength and back and leg strength. Body composition was measured using bioelectric impedance. The exercise professional recommended a slow but progressive approach to achieving a regular exercise program for Mrs. P and recommended a progressive resistance training program, flexibility training, and regimen of cardiopulmonary exercise. Ultimately, the exercise program will need to become a regular part of Mrs. P's treatment plan. It was also recommended that she seek the counsel of a registered dietician to help promote better general health.

Exercise Progression

Resistance training began with a combination of 8 to 10 movements consisting of both bodyweight and resistance band exercises, two days per week. One set of 10 to 15 repetitions was performed for each exercise. While 1- to 2-minute rest periods were appropriate, early training rest periods were variable. Each session was completed with light full-body static stretching. Each stretch was held for 10 to 15 seconds. Aerobic sessions were scheduled on days in which resistance training was not done. Because of Mrs. P's preference, aerobic training was conducted twice per week in a swimming pool. Her group instructor aided her in completion of one or two 5- or 10-minute intervals of activity. All early training was kept below the point of volitional fatigue.

Resistance training frequency was increased to three or four times per week. While repetitions remained in the 10 to 15 range, the number of sets was increased to two or three. To accommodate this change, different muscle groups were trained on different days. Aerobic training progressed from intervals to single sessions of 20 to 30 minutes, three or four days per week. The client also began to explore other aerobic modes. Her training schedule remained flexible and was adjusted as needed depending on her symptoms.

Outcomes

Following some minor setbacks as she learned her exercise tolerances, Mrs. P was able to establish a routine that fit within the structure of her life. Her physical condition improved, as did her quality of life. The combination of her therapies and dietary modifications has been effective. Although she still deals with pain, it is dramatically less than before. The strain on her home and work relationships is better.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Understanding and recommending exercise for clients with joint replacements

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement (figure 3.7). While total hip and knee replacements are the most common, other joints are also replaced, including, but not limited to, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. In 2011 approximately 1.4 million joint replacement surgeries were performed in the United States, including over 640,000 knee and 300,000 hip total joint replacements. The cumulative number of individuals living in the United States with knee replacements is estimated at over 4 million, with a higher prevalence in females than males and overall prevalence increasing with age. The financial cost of joint replacements was estimated at approximately $16 billion in the United States in 2006 and was projected to rise with the increasing aging population and prevalence of obesity.

Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty) involves replacement of part or all of a damaged joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Pathophysiology of Joint Replacements

Several risk factors leading to joint replacement have been identified; these include age, sex, body mass index, developmental disorders, fractures, injury, and diseases leading to degeneration of one or more aspects of the joint. However, both primary and secondary OA was the principal diagnosis for 85.3% and 97.3% of hip and knee total replacement surgeries, respectively, in the United States in 2011.

Common Medications Given to Individuals With Joint Replacements

Arthroplasty is an invasive procedure, and the medications commonly associated with the surgery include anesthesia, sedatives, intravenous prescription opioid pain relievers (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), and antibiotics. Once the individual is released from the hospital following surgery and acute recovery, various OTC and prescription medications are prescribed (see medications table 3.4 near the end of the chapter). Over-the-counter medication for mild to moderate pain relief (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]) and reducing inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen [Advil]) may be taken for up to several weeks postsurgery; however, as noted earlier, caution is advised as NSAIDs increase the risk of heart attack and stroke with higher doses and longer use. Prescription oral opioid pain relievers may be prescribed for those with more severe pain; however, extended use of these drugs is not recommended because they are highly addictive. Oral antibiotics are also typically prescribed to prophylactically prevent infections, and while side effects are not common, they may include nausea, vomiting, GI distress, or allergic reaction. Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin) are also commonly prescribed because surgery increases the risk of blood clots.

Effects of Exercise in Individuals With Joint Replacements

Postoperative physical activity and exercise to stimulate leg blood flow are encouraged to reduce the risk of blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are strikingly common; 40% to 60% of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients who did not receive antithrombosis treatment had a confirmed postoperative diagnosis.

Key Point

Postoperative physical activity is encouraged in individuals with joint replacements to stimulate leg blood flow and reduce the risk of blood clots. Clearance to exercise from a physician or other health care professional should be obtained prior to initiating exercise.

Exercise Recommendations for Clients With Joint Replacements

Recovery and rehabilitation following joint replacement are highly individualized, as the healing and pain associated with the surgery can last weeks to months, as can the adjustment to the new joint and its movement. During this period of reduced activity, loss of muscle strength will accrue and should be considered and addressed. Initially the client's physician and physical therapist direct the exercise prescription to restore normal and healthy movement patterns and strengthen the joint and associated structures and musculature.

Due to the invasive nature of the surgery, the various types of joint replacement (i.e., partial or total), individualized responses to recovery and rehabilitation, and inconsistencies in the literature, specific exercise prescription is highly individualized. Following the initial recovery and rehabilitation phase, evidence of functionally stable and painless movement patterns of the affected joint is necessary before the client begins a strength and conditioning program. General guidelines for such a program include the following:

- A period of six months is recommended before engaging in vigorous exercise.

- An initial period of low-impact aerobic exercises (i.e., those that combine cyclic low limb movement patterns with low rotational and minimal impact forces) is highly recommended. This includes cycling, swimming, walking, low-impact aerobics, weight training, and cross-country skiing.

- High-impact activities and contact sports should be avoided.

- Exercise and physical activity that include frequent jumping or plyometrics are contraindicated in most cases but should be evaluated individually.

- The client's prior exercise and sporting experience should be considered in these recommendations, as this may indicate an increased tolerance for those activities.

In conjunction it is recommended that exercise professionals refer to the generally accepted guidelines adopted by the U.S. DHHS for developing exercise sessions and programs for adults with joint arthroplasty, while ensuring that the exercise prescription is individualized in its implementation and progression to reflect the limitations, strengths, weaknesses, and goals of the client. The recommendations for a resistance training program are to improve overall muscular strength and endurance; however, a loss of muscle mass may also have occurred, and if so should be addressed. Initial recommendations are two to four sets (one set if the client is sedentary or low in conditioning) of 8 to 12 repetitions per exercise at an initial light to moderate intensity, one or two times per week. To increase flexibility and range of motion it is recommended that clients initially complete static stretches three to seven times per week of all major muscle groups and hold each stretch for 15 to 30 seconds. Recommendations for aerobic exercise are to engage large muscle groups (e.g., brisk walking) at an initial light to moderate intensity for at least 10 minutes three or more times per day, three or more days per week, progressing to at least 300 minutes of moderate or 150 minutes of vigorous (or an equivalent combination of both intensities) per week. Exercise should cease immediately if there is any pain, with referral to a physician or other health care professional. Program design guidelines for clients with joint replacements are summarized in table 3.6.

Save

Save

Save

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Professional opportunities for those training special populations

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area.

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area. Various special populations are expected to grow in size with the increasing rate of inactivity in the general population compounded with specific growth in certain special populations. Almost one-half of all U.S. adults (117 million) have at least one chronic medical condition (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis), with more than two chronic conditions reported in over one-quarter of adults (60 million). The current number of Americans over the age of 65 is calculated at over 40 million and is expected to increase to approximately 72 million persons by the year 2030. Because chronic conditions increase in prevalence in older populations, these figures indicate that an overwhelming number of persons in our society and a growing segment of our society will be classified as a part of special populations.

Health care costs associated with obesity and sedentary lifestyles are greater than $90 billion annually in the United States alone. These escalating costs place undue stress on both individual and employer health insurance systems. The medical system has made dramatic advances in the care of persons with disease, in particular in the area of emergency care. Survival and recovery have significantly improved in many conditions considered to have questionable outcomes only a few decades ago. This dramatically extended life expectancy, from 66 years in males and 71.7 years in females in 1950 to 72.1 years in males and 79.0 years in females in 1990. By the year 2009, the predicted life span from birth had grown to 76.0 years for men and to 80.9 years for women. Thus, during the same period of time in which length of life increased by approximately 10 years, our society became increasingly inactive. This has resulted in progressive extension of the length of life (quantity of life) with significant reductions in the level of functional independence during the later years of life (quality of life).

The medical system may be an important referral source of new clients to the exercise professional with expertise with special populations. Chapter 2 of this text provides detailed discussions of the health appraisal process and the steps to determine the appropriateness of a medical clearance for a particular potential client. The medical clearance process establishes a means of communication between the exercise professional and a licensed health care professional. Medical clearance provides professional authorization for exercise testing and training in persons who exhibit particular risk factors. This process may also establish a line of communication between the exercise professional and the medical professionals with regard to future patients and their need to engage in purposeful exercise programming outside of the medical treatment environment.

Discharge plans from medical care, particularly physical therapy, usually involve some recommendations for activities and exercise strategies for the patient. Patients may have a limited background in exercise and active lifestyles, and their only experience in these areas may be the therapeutic activities in the rehabilitative setting. Thus, it is unlikely that they will seek to begin a structured exercise program with professional support even if this has been recommended by the clinician. It is recommended that the exercise professional establish working relationships with medical professionals in the community. In this way, the patient can be directly referred by the medical professional to an associated exercise professional who can provide the appropriate guidance and supervision.

Unfortunately, in many situations the rehabilitation plan must be carried out with time limitations related to the patient's medical insurance coverage. The therapeutic plan of care often must concentrate on the most vital skills of daily living in order to enhance the level of functional independence in the limited time available. Thus, many patients are discharged from the rehabilitation setting in a condition that warrants continued physical training. Exercise professionals with advanced background in training of special populations can certainly provide the needed assessment and training of these discharged patients, with clearance and recommendations from the clinician.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Case study: client with fibromyalgia

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records.

Case Study

- Sex: Female

- Race: Caucasian

- Age: 43

- Height: 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m)

- Weight: 145 pounds (66 kg)

- Body fat: 32%

- Body mass index: 25.7

- Resting heart rate: 72 beats/min

- Blood pressure: 142/94 mmHg

- Temperature: Normal

History

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records. For several years she has noticed diffuse muscle discomfort throughout her upper body and thighs. She has made several modifications to her workstation to help alleviate her issues, but this has been unsuccessful. Her physical discomfort has made working quite difficult as well as straining her relationships at home. Following a serious car accident, she noticed a marked increase in her symptoms and great difficulty sleeping. After minimal success with physical therapy, she was diagnosed with FM by her primary physician. The physician prescribed NSAIDs, antidepressants, and a sleep aid. Having attempted alternative forms of treatment, Mrs. P sought the help of an exercise professional who was knowledgeable about FM.

Goals

Mrs. P hopes to work with her exercise professional to reach the following goals:

- Alleviate consistent muscular pain

- Improve quality of work and home life

- Establish exercise programming as a regular part of treatment

- Improve overall fitness

Initial Training

Having received clearance from her primary physician, Mrs. P met with a certified exercise specialist at a facility near her home. The exercise professional took a full medical history. Traditional submaximal aerobic and muscular exercise testing was attempted, but results were not accurate due to Mrs. P's low physical capacity. As an alternative, the exercise specialist performed the University of Houston Non-Exercise Test to assess her aerobic capacity and a dynamometer battery consisting of handgrip strength and back and leg strength. Body composition was measured using bioelectric impedance. The exercise professional recommended a slow but progressive approach to achieving a regular exercise program for Mrs. P and recommended a progressive resistance training program, flexibility training, and regimen of cardiopulmonary exercise. Ultimately, the exercise program will need to become a regular part of Mrs. P's treatment plan. It was also recommended that she seek the counsel of a registered dietician to help promote better general health.

Exercise Progression

Resistance training began with a combination of 8 to 10 movements consisting of both bodyweight and resistance band exercises, two days per week. One set of 10 to 15 repetitions was performed for each exercise. While 1- to 2-minute rest periods were appropriate, early training rest periods were variable. Each session was completed with light full-body static stretching. Each stretch was held for 10 to 15 seconds. Aerobic sessions were scheduled on days in which resistance training was not done. Because of Mrs. P's preference, aerobic training was conducted twice per week in a swimming pool. Her group instructor aided her in completion of one or two 5- or 10-minute intervals of activity. All early training was kept below the point of volitional fatigue.

Resistance training frequency was increased to three or four times per week. While repetitions remained in the 10 to 15 range, the number of sets was increased to two or three. To accommodate this change, different muscle groups were trained on different days. Aerobic training progressed from intervals to single sessions of 20 to 30 minutes, three or four days per week. The client also began to explore other aerobic modes. Her training schedule remained flexible and was adjusted as needed depending on her symptoms.

Outcomes

Following some minor setbacks as she learned her exercise tolerances, Mrs. P was able to establish a routine that fit within the structure of her life. Her physical condition improved, as did her quality of life. The combination of her therapies and dietary modifications has been effective. Although she still deals with pain, it is dramatically less than before. The strain on her home and work relationships is better.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Understanding and recommending exercise for clients with joint replacements

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement (figure 3.7). While total hip and knee replacements are the most common, other joints are also replaced, including, but not limited to, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. In 2011 approximately 1.4 million joint replacement surgeries were performed in the United States, including over 640,000 knee and 300,000 hip total joint replacements. The cumulative number of individuals living in the United States with knee replacements is estimated at over 4 million, with a higher prevalence in females than males and overall prevalence increasing with age. The financial cost of joint replacements was estimated at approximately $16 billion in the United States in 2006 and was projected to rise with the increasing aging population and prevalence of obesity.

Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty) involves replacement of part or all of a damaged joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Pathophysiology of Joint Replacements

Several risk factors leading to joint replacement have been identified; these include age, sex, body mass index, developmental disorders, fractures, injury, and diseases leading to degeneration of one or more aspects of the joint. However, both primary and secondary OA was the principal diagnosis for 85.3% and 97.3% of hip and knee total replacement surgeries, respectively, in the United States in 2011.

Common Medications Given to Individuals With Joint Replacements

Arthroplasty is an invasive procedure, and the medications commonly associated with the surgery include anesthesia, sedatives, intravenous prescription opioid pain relievers (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), and antibiotics. Once the individual is released from the hospital following surgery and acute recovery, various OTC and prescription medications are prescribed (see medications table 3.4 near the end of the chapter). Over-the-counter medication for mild to moderate pain relief (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]) and reducing inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen [Advil]) may be taken for up to several weeks postsurgery; however, as noted earlier, caution is advised as NSAIDs increase the risk of heart attack and stroke with higher doses and longer use. Prescription oral opioid pain relievers may be prescribed for those with more severe pain; however, extended use of these drugs is not recommended because they are highly addictive. Oral antibiotics are also typically prescribed to prophylactically prevent infections, and while side effects are not common, they may include nausea, vomiting, GI distress, or allergic reaction. Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin) are also commonly prescribed because surgery increases the risk of blood clots.

Effects of Exercise in Individuals With Joint Replacements

Postoperative physical activity and exercise to stimulate leg blood flow are encouraged to reduce the risk of blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are strikingly common; 40% to 60% of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients who did not receive antithrombosis treatment had a confirmed postoperative diagnosis.

Key Point

Postoperative physical activity is encouraged in individuals with joint replacements to stimulate leg blood flow and reduce the risk of blood clots. Clearance to exercise from a physician or other health care professional should be obtained prior to initiating exercise.

Exercise Recommendations for Clients With Joint Replacements

Recovery and rehabilitation following joint replacement are highly individualized, as the healing and pain associated with the surgery can last weeks to months, as can the adjustment to the new joint and its movement. During this period of reduced activity, loss of muscle strength will accrue and should be considered and addressed. Initially the client's physician and physical therapist direct the exercise prescription to restore normal and healthy movement patterns and strengthen the joint and associated structures and musculature.

Due to the invasive nature of the surgery, the various types of joint replacement (i.e., partial or total), individualized responses to recovery and rehabilitation, and inconsistencies in the literature, specific exercise prescription is highly individualized. Following the initial recovery and rehabilitation phase, evidence of functionally stable and painless movement patterns of the affected joint is necessary before the client begins a strength and conditioning program. General guidelines for such a program include the following:

- A period of six months is recommended before engaging in vigorous exercise.

- An initial period of low-impact aerobic exercises (i.e., those that combine cyclic low limb movement patterns with low rotational and minimal impact forces) is highly recommended. This includes cycling, swimming, walking, low-impact aerobics, weight training, and cross-country skiing.

- High-impact activities and contact sports should be avoided.

- Exercise and physical activity that include frequent jumping or plyometrics are contraindicated in most cases but should be evaluated individually.

- The client's prior exercise and sporting experience should be considered in these recommendations, as this may indicate an increased tolerance for those activities.

In conjunction it is recommended that exercise professionals refer to the generally accepted guidelines adopted by the U.S. DHHS for developing exercise sessions and programs for adults with joint arthroplasty, while ensuring that the exercise prescription is individualized in its implementation and progression to reflect the limitations, strengths, weaknesses, and goals of the client. The recommendations for a resistance training program are to improve overall muscular strength and endurance; however, a loss of muscle mass may also have occurred, and if so should be addressed. Initial recommendations are two to four sets (one set if the client is sedentary or low in conditioning) of 8 to 12 repetitions per exercise at an initial light to moderate intensity, one or two times per week. To increase flexibility and range of motion it is recommended that clients initially complete static stretches three to seven times per week of all major muscle groups and hold each stretch for 15 to 30 seconds. Recommendations for aerobic exercise are to engage large muscle groups (e.g., brisk walking) at an initial light to moderate intensity for at least 10 minutes three or more times per day, three or more days per week, progressing to at least 300 minutes of moderate or 150 minutes of vigorous (or an equivalent combination of both intensities) per week. Exercise should cease immediately if there is any pain, with referral to a physician or other health care professional. Program design guidelines for clients with joint replacements are summarized in table 3.6.

Save

Save

Save

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Professional opportunities for those training special populations

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area.

The exercise professional with expertise in the training of special populations (via formal education and professional certifications) is properly positioned to meet the growing need for professionals with appropriate background in this area. Various special populations are expected to grow in size with the increasing rate of inactivity in the general population compounded with specific growth in certain special populations. Almost one-half of all U.S. adults (117 million) have at least one chronic medical condition (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, arthritis), with more than two chronic conditions reported in over one-quarter of adults (60 million). The current number of Americans over the age of 65 is calculated at over 40 million and is expected to increase to approximately 72 million persons by the year 2030. Because chronic conditions increase in prevalence in older populations, these figures indicate that an overwhelming number of persons in our society and a growing segment of our society will be classified as a part of special populations.

Health care costs associated with obesity and sedentary lifestyles are greater than $90 billion annually in the United States alone. These escalating costs place undue stress on both individual and employer health insurance systems. The medical system has made dramatic advances in the care of persons with disease, in particular in the area of emergency care. Survival and recovery have significantly improved in many conditions considered to have questionable outcomes only a few decades ago. This dramatically extended life expectancy, from 66 years in males and 71.7 years in females in 1950 to 72.1 years in males and 79.0 years in females in 1990. By the year 2009, the predicted life span from birth had grown to 76.0 years for men and to 80.9 years for women. Thus, during the same period of time in which length of life increased by approximately 10 years, our society became increasingly inactive. This has resulted in progressive extension of the length of life (quantity of life) with significant reductions in the level of functional independence during the later years of life (quality of life).

The medical system may be an important referral source of new clients to the exercise professional with expertise with special populations. Chapter 2 of this text provides detailed discussions of the health appraisal process and the steps to determine the appropriateness of a medical clearance for a particular potential client. The medical clearance process establishes a means of communication between the exercise professional and a licensed health care professional. Medical clearance provides professional authorization for exercise testing and training in persons who exhibit particular risk factors. This process may also establish a line of communication between the exercise professional and the medical professionals with regard to future patients and their need to engage in purposeful exercise programming outside of the medical treatment environment.

Discharge plans from medical care, particularly physical therapy, usually involve some recommendations for activities and exercise strategies for the patient. Patients may have a limited background in exercise and active lifestyles, and their only experience in these areas may be the therapeutic activities in the rehabilitative setting. Thus, it is unlikely that they will seek to begin a structured exercise program with professional support even if this has been recommended by the clinician. It is recommended that the exercise professional establish working relationships with medical professionals in the community. In this way, the patient can be directly referred by the medical professional to an associated exercise professional who can provide the appropriate guidance and supervision.

Unfortunately, in many situations the rehabilitation plan must be carried out with time limitations related to the patient's medical insurance coverage. The therapeutic plan of care often must concentrate on the most vital skills of daily living in order to enhance the level of functional independence in the limited time available. Thus, many patients are discharged from the rehabilitation setting in a condition that warrants continued physical training. Exercise professionals with advanced background in training of special populations can certainly provide the needed assessment and training of these discharged patients, with clearance and recommendations from the clinician.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Case study: client with fibromyalgia

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records.

Case Study

- Sex: Female

- Race: Caucasian

- Age: 43

- Height: 5 feet, 3 inches (1.60 m)

- Weight: 145 pounds (66 kg)

- Body fat: 32%

- Body mass index: 25.7

- Resting heart rate: 72 beats/min

- Blood pressure: 142/94 mmHg

- Temperature: Normal

History

Mrs. P is a receptionist in a dental office. Her job entails sitting for long periods of time, entering information into a computer, and retrieving dental records. For several years she has noticed diffuse muscle discomfort throughout her upper body and thighs. She has made several modifications to her workstation to help alleviate her issues, but this has been unsuccessful. Her physical discomfort has made working quite difficult as well as straining her relationships at home. Following a serious car accident, she noticed a marked increase in her symptoms and great difficulty sleeping. After minimal success with physical therapy, she was diagnosed with FM by her primary physician. The physician prescribed NSAIDs, antidepressants, and a sleep aid. Having attempted alternative forms of treatment, Mrs. P sought the help of an exercise professional who was knowledgeable about FM.

Goals

Mrs. P hopes to work with her exercise professional to reach the following goals:

- Alleviate consistent muscular pain

- Improve quality of work and home life

- Establish exercise programming as a regular part of treatment

- Improve overall fitness

Initial Training

Having received clearance from her primary physician, Mrs. P met with a certified exercise specialist at a facility near her home. The exercise professional took a full medical history. Traditional submaximal aerobic and muscular exercise testing was attempted, but results were not accurate due to Mrs. P's low physical capacity. As an alternative, the exercise specialist performed the University of Houston Non-Exercise Test to assess her aerobic capacity and a dynamometer battery consisting of handgrip strength and back and leg strength. Body composition was measured using bioelectric impedance. The exercise professional recommended a slow but progressive approach to achieving a regular exercise program for Mrs. P and recommended a progressive resistance training program, flexibility training, and regimen of cardiopulmonary exercise. Ultimately, the exercise program will need to become a regular part of Mrs. P's treatment plan. It was also recommended that she seek the counsel of a registered dietician to help promote better general health.

Exercise Progression

Resistance training began with a combination of 8 to 10 movements consisting of both bodyweight and resistance band exercises, two days per week. One set of 10 to 15 repetitions was performed for each exercise. While 1- to 2-minute rest periods were appropriate, early training rest periods were variable. Each session was completed with light full-body static stretching. Each stretch was held for 10 to 15 seconds. Aerobic sessions were scheduled on days in which resistance training was not done. Because of Mrs. P's preference, aerobic training was conducted twice per week in a swimming pool. Her group instructor aided her in completion of one or two 5- or 10-minute intervals of activity. All early training was kept below the point of volitional fatigue.

Resistance training frequency was increased to three or four times per week. While repetitions remained in the 10 to 15 range, the number of sets was increased to two or three. To accommodate this change, different muscle groups were trained on different days. Aerobic training progressed from intervals to single sessions of 20 to 30 minutes, three or four days per week. The client also began to explore other aerobic modes. Her training schedule remained flexible and was adjusted as needed depending on her symptoms.

Outcomes

Following some minor setbacks as she learned her exercise tolerances, Mrs. P was able to establish a routine that fit within the structure of her life. Her physical condition improved, as did her quality of life. The combination of her therapies and dietary modifications has been effective. Although she still deals with pain, it is dramatically less than before. The strain on her home and work relationships is better.

Learn more about NSCA's Essentials of Training Special Populations.

Understanding and recommending exercise for clients with joint replacements

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Joint replacement surgery (also known as arthroplasty) involves replacement of part (e.g., articular cartilage) or all of a damaged or arthritic joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement (figure 3.7). While total hip and knee replacements are the most common, other joints are also replaced, including, but not limited to, shoulder, elbow, and ankle. In 2011 approximately 1.4 million joint replacement surgeries were performed in the United States, including over 640,000 knee and 300,000 hip total joint replacements. The cumulative number of individuals living in the United States with knee replacements is estimated at over 4 million, with a higher prevalence in females than males and overall prevalence increasing with age. The financial cost of joint replacements was estimated at approximately $16 billion in the United States in 2006 and was projected to rise with the increasing aging population and prevalence of obesity.

Joint replacement surgery (arthroplasty) involves replacement of part or all of a damaged joint with a metal, plastic, or ceramic prosthesis in order to return the joint to normal pain-free movement.

Pathophysiology of Joint Replacements

Several risk factors leading to joint replacement have been identified; these include age, sex, body mass index, developmental disorders, fractures, injury, and diseases leading to degeneration of one or more aspects of the joint. However, both primary and secondary OA was the principal diagnosis for 85.3% and 97.3% of hip and knee total replacement surgeries, respectively, in the United States in 2011.

Common Medications Given to Individuals With Joint Replacements

Arthroplasty is an invasive procedure, and the medications commonly associated with the surgery include anesthesia, sedatives, intravenous prescription opioid pain relievers (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), and antibiotics. Once the individual is released from the hospital following surgery and acute recovery, various OTC and prescription medications are prescribed (see medications table 3.4 near the end of the chapter). Over-the-counter medication for mild to moderate pain relief (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]) and reducing inflammation (e.g., ibuprofen [Advil]) may be taken for up to several weeks postsurgery; however, as noted earlier, caution is advised as NSAIDs increase the risk of heart attack and stroke with higher doses and longer use. Prescription oral opioid pain relievers may be prescribed for those with more severe pain; however, extended use of these drugs is not recommended because they are highly addictive. Oral antibiotics are also typically prescribed to prophylactically prevent infections, and while side effects are not common, they may include nausea, vomiting, GI distress, or allergic reaction. Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin (Coumadin) are also commonly prescribed because surgery increases the risk of blood clots.

Effects of Exercise in Individuals With Joint Replacements

Postoperative physical activity and exercise to stimulate leg blood flow are encouraged to reduce the risk of blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which are strikingly common; 40% to 60% of total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients who did not receive antithrombosis treatment had a confirmed postoperative diagnosis.

Key Point